-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2013; 3(7): 249-260

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20130307.01

Strengthening Capacities of Communities for Sustainable Forest Management: The Case of Renk County, South Sudan

Loice M. A. Omoro1, Edinam K. Glover2

1Viikki Tropical Resources Institute, Department of Forest Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland

2Faculty of Law, University of Helsinki, Finland

Correspondence to: Edinam K. Glover, Faculty of Law, University of Helsinki, Finland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Local communities in Renk, South Sudan collectively own their land and therefore, should be able to benefit from its resources. However, the communities are unable to do so due to inadequacies in capacity to manage particularly the forests resources in a way that can sustain both the resources and the people. Strengthening capacities for communities and institutions is underscored to be central in ensuring sustainable use of resources. This study assessed the capacities of the local communities in implementing sustainable forest management as well as the capacities of research and development institutions to provide the necessary training and extension services to strengthen the capacities of the communities to implement sustainable forest management. A cross-sectional survey of respondents representing 21% of the estimated population of 67,182 in Renk was interviewed using participatory methodologies and semi-structured questionnaire. Results showed that sustainable forestry activities are limited in Renk County although the communities are aware of the benefits of forests. The study highlighted some of the challenges affecting forestry development and sustainable forestry practices which, are mainly related to inadequate capacities within the forestry institution and among the communities to effectively implement sustainable forestry. The study concludes that by strengthening capacities and collaboration between institutions and stakeholders, Renk County has opportunities to benefit from sustainable forestry.

Keywords: KeywordsCapacity Building, Community Knowledge, Forest Governance, Perception, Renk County, Skills, South Sudan

Cite this paper: Loice M. A. Omoro, Edinam K. Glover, Strengthening Capacities of Communities for Sustainable Forest Management: The Case of Renk County, South Sudan, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 3 No. 7, 2013, pp. 249-260. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20130307.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Within the development community, capacity strengthening is debated and developing countries in particular are encouraged to strengthen the capacities within their public and private institutions in order to address challenges of sustainable development[1, 2]. Capacity strengthening is the enhancement of existing human and institutional capabilities to implement policies and other activities for development. It is a process undertaken externally or internally with the aim of improving the performances of regional and national development activities. The process of capacity strengthening includes strengthening of skills and competencies, training of individuals, and infrastructural development of research and development institutions[3]. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Capacity strengthening is synonymously used with capacity building and is stated to be a continuous development process involving many stakeholders; who among others include governmental, non-governmental organizations, local communities and academics who steer development. Capacity building is also considered to be essential for sustainable development because it enables people to optimally allocate and effectively use factors of production (i.e., land, labour and capital) as well as making management and power relation decisions[4, 5]. Studies have shown that differences in education levels as an aspect of capacity building influences labour productivity with regard to investment decision making. In a study,[6] four years’ of schooling was found to increase farmers’ output by 8.7 % while in another[7] found that farmers invested on high pay-off inputs such as hybrids based on their levels of educational.[8] suggests that the benefits of capacity building are best observed at community level and he argues that at this level, capacity building enhances the communities’ moral sense of duty with respect to resource use. Agricultural productivity in sub-Saharan Africa has declined due to many reasons among which are limited training opportunities, aging of qualified staff and disproportionate recruitment of qualified staff in institutions charged with development[12]. The situation is even more acute in the forestry sector where in many of the sub-Saharan African countries forestry is not a major backbone of the economy because value-addition and fair trade in timber and timber products is minimal[13]. This is due to either weak or limited human resource development restricting the abilities to effectively carry out forestry research which, consequently affect the development of forest resources into income-generating enterprises that could generate revenue and alleviate rural poverty[18]. Consequently, there is increased need for strengthening of capacity at organizational levels to include identification of capacity gaps and existing knowledge in order to plan and execute appropriate interventions so as to make proper investments for sustainable forest management[2, 9, 10, 11, 13]. Sustainable forest management has been variously defined[14, 15, 16 and it entails all ways of managing forest resources for specific objectives which ensure continuous flow of the desired products and service. In the newly independent country of South Sudan there are numerous capacity gaps that beset development activities and these include implementation of sustainable forest management. In particular, these are limitations on human resource capacities in institutions that are charged with forestry development. The Civil Authority for the New Sudan[17] of 1996 was to build the capacities of personnel to administer and deliver public services to the people of South Sudan. Institutions were set up to offer education and training in several sectors including forestry[18].[19] point out that training cannot be divorced from education because the purpose of formal education is to impart knowledge and develop capacities of individuals to be resourceful and self-reliant. Unfortunately, institutions that offer middle and field level trainings for personnel to steer forestry development at the community level are inadequate or altogether not available, underscoring the need for strengthening of capacities of institutions and communities.In Renk County, the losses on forest ecosystem are more pronounced because these resources are limited, consequently, appropriate activities and methodologies are needed to deter or alternatively alter the rates of losses of remaining forest resources as part of sustainable forest management[20, 21, 22]. Unfortunately, in the absence of middle and field level staff or with staff whose capacities are limited, strengthening of capacities are necessary to effectively provide extension services to enable communities undertake sustainable forest management. Extension is a process which enables local people to become familiar with new knowledge and skills and through which government support services can learn about local priorities and needs[23].Against this backdrop, this study reports on the interventions regarding capacity strengthening in sustainable forestry for local communities and institutions in Renk County. Specifically the study assessed knowledge and skills in forestry activities by local communities; capacities of institutions in promoting sustainable forestry; and finally makes recommendations on ways of strengthening communities and institutional capacities for sustainable forest management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

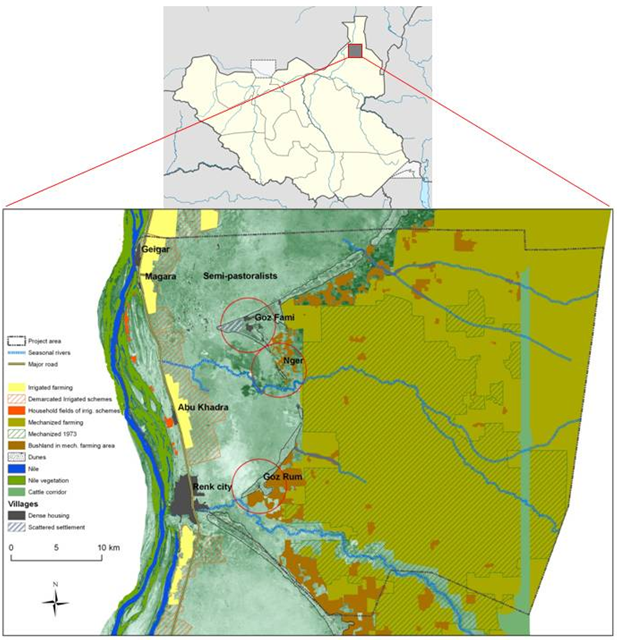

- This study was conducted in Renk County (Fig.1) which is one of the eleven counties in the Upper Nile State of South Sudan. Renk County occupies an area of about 32,000 square kilometers in the north of the state and has two distinct seasons. The wet season occurs during the months of June-October while the dry season occurs between November and May. The population of Renk county is estimated at 67,182[24] and the people mainly rely on agriculture and livestock for their livelihoods.In South Sudan, forests and woodlands cover about 29% of the total land area and comprise mainly of tropical forests of mahogany and teaks in the south and acacia woodlands in the north. There were no forest management instituted during the war and this is said to have contributed to the irony that in some regions (e.g. Western Equatoria) forests remained intact because of the limited trade then with the North, and yet in other regions (e.g. Eastern Equatoria) the army cleared the forests for trade to finance the war[24]. Renk County on the other hand, is located to the far north of South Sudan and in a relatively drier area. It is not endowed with as much forest resources as other parts of South Sudan. The original forest cover in the country was estimated as 6.5% but has since decreased to 0% during the period between 1973 and 2006[25]. There are few remaining tree resources which are sparsely populated and consist mainly of acacia woodlands which are constantly overexploited for charcoal making for the readily available markets in the North. The trees are also poorly harvested for gum tapping through debarking or by fire all of which continue to deplete these resources. In the past, forest sustained people’s livelihoods through provisions of gums, resins and fodder especially during drought periods[20].

| Figure 1. Map of South Sudan showing the study area in Renk County Source: Wikipeadia and Lamptess Report; 2010/Afrikan Sarvi |

2.2. Data Collection Methods

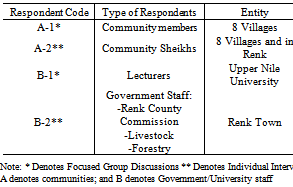

- Several participatory methodologies were employed for data collection. These were focused group discussions (FGDs)[26, 27, 28], SWOT analysis[31] and participant observation during visits to the villages. Individual interviews using semi-structured checklists were also held with different members of staff from three government departments with bearing on forest resources. Table 1 shows the categorization of the respondents and the respective methodology adopted in gathering data. The focused group discussions with communities were facilitated through translations from English to Arabic while group discussions and interviews with individual government staff were conducted in English. Background information and other secondary data were obtained from an earlier report[30] which was used to cross check the information from the field. Other information was obtained through observations during the field visits. In many of the villages, the respondents’ numbers varied between 5-10 people depending on the size of the village. Many of the respondents were males with exceptions of one Village, Sheikh Mohammed where there were 3 females and among the University staff where there were four women and 6 men. Four male government personnel were interviewed, each representing the four departments of Forest, Livestock, Agriculture and County Commission. Other respondents 125 respondents were community members from 8 villages namely, Goz Roum (30), Magara (17), Mohamed Sheikh Village (5 including 3), Goz Famin (35 men) Nger Village (5), Sheikh Yasin (7), Abu Khadra(13) and Geiga villages(15). The UNU staffs were 7 with 2 local opinion leaders including chiefs making a total of 9. In total 147 respondents were interviewed. During both the FGDs and individual interviews, a checklist of questions was used to capture the information to accomplish the study objectives. In addition, other participatory methods of SWOT analyses were used to cross check and identify specific issues during the focused group discussions. Background information and other secondary data obtained from an earlier report[32] were used to cross check the information collected from the field.

|

2.3. Data analyses

- The responses obtained from the interviewees were analysed using content analysis in relation to the study objectives[7, 5]. SWOT analyses were accomplished by dividing the participants into four groups and each group was asked to discuss what they understood to be Strengths, Weakness Opportunity or Weakness in respect of sustainable forestry in Renk; after which the outcomes were jointly discussed in a plenary and endorsed. The content analyses were based on 6 categories outlined in Table 2.

|

3. Results and Discussions

- The respondents had common opinions on all the categories across the villages as would be expected in Focused group discussions[1, 26, 31, 33]. The results from each of the categories under which the analyses were done are as follows:

3.1. Respondents and Livelihood Sources

- Results of a proportionate random sample representing 22% of the estimated total population of 67,182 showed that the respondents from the 8 villages mentioned that their major sources of livelihood were agriculture and livestock although a study by[51] shows that other sources such as employment (45%) and petty trading (26%) are increasingly becoming more pronounced. Agriculture is practiced at three scales namely: mechanized agriculture both large scale (average 1000 feddans) and small scale (range 180-250 feddans) which is rain-fed; and irrigated agriculture. Mechanized rain-fed and irrigated agriculture are specifically for production of Dura, sorghum although respondents stated that previously cotton was the major crop in the irrigation schemes but has since been abandoned due to high costs and pest infestations. The Dura is sold both locally and in other markets and the local sales offer opportunities for the communities to engage in petty trading. Although agriculture was mentioned to be disaggregated, the respondents stated that they do not own the large mechanized farms instead the owners come from other areas outside Renk County areas such as Kosti, Khartoum and Rebek. The participation of the locals in these farms is therefore, reduced to being casual labourers who when hired by the large scale farmers derive their livelihoods. As men work in the mechanized farms, the women farm in home gardens where they practice mixed farming and employ measures for soil fertility improvement by using animal manure.A common challenge mentioned by the respondents was low crop yields from farms that have been observed over time. During the interviews, observation made in the fields was that, there was widespread infestation of Striga hermonthica, a weed considered as an indicator for low soil fertility[34, 35]. Striga infestation is common in many parts including Sudan where[33] many farmers in the Republic of Sudan mentioned Striga weed as a problem especially in fields that are continuously under monocropping[ibid.]. As[36] rightly points out, Striga problem in Africa is intimately associated with intensification of land use associated with monocropping of cereals as is the case in Renk where it is common on mechanized farms for production of Dura. Inclusion of trees on farms in different configuration is one way in which soil fertility can be enhanced on such farms[37, 28, 38]. In the mechanized farms, soil fertility improvement are supposed to be based on recommendations by then government of Sudan’s decree of 1994 which stipulates that 10% of the total area under mechanized farms be planted with shelterbelts. Planting or retention of natural forest of Acacia senegal, Acacia seyal, Acacia mellifera and Acacia seyal var. fistula in sloppy farms and stream banks[21, 22]. Similarly, the South Sudan’s forest policy also stresses that 10% of the mechanized farms be under trees. However, these recommendations are not adhered to by the mechanized farmers and therefore, many of the mechanized farms are devoid of trees because the farmers perceive these recommendations to be in the interests of the government[39]. This finding shows a capacity gap among the farmers and is an indication that the communities are not aware of the role of trees in soil fertility improvement. Integration of fast growing nitrogen fixing trees into the farms as reinforcements to create shelter belts or as improved fallows as advocated for in the forest policies can alleviate soil fertility challenge as well as form part of sustainable forest management. The trees would also provide other valuable products[40] and services; including spreading risks in case of crop failure to strengthen the economic[41], social[21] and ecological basis of agricultural production[41] in this county.

3.2. Knowledge on Importance of Trees

- An assessment of knowledge and skills the local communities have in forestry activities based on interviews, showed varied responses regarding the importance of forests. The majority of respondents from group discussions stated that they were aware of the values of trees in the landscape and that trees are useful as sources of livelihood. They gave the example of Acacia seyal from which gum is extracted for sale (Ngeer and Goz Roum villages). Field observations further indicated that in all the villages visited, there were trees around the villages including farms. When asked why the communities retained trees on their farms, the respondents had mixed views: In some villages (Magara and Goz Roum), the communities’ perception was that when trees are left standing on farms they “attract rain”. In the other villages, some respondents expressed their reservations about retaining trees on their farms. Their assertions were that when trees are retained on farms they compete with crops for water, light and nutrients and therefore, would only consider retaining the trees if they did not pose any competition with crops. The reservations that farmers have about trees competing with crops are true in some instances depending on the type of trees in question. A study in Morogoro, Tanzania (with rainfall measuring 870 mm a-1) to assess roots of some five tree species (including nitrogen fixing Leucaena. leucocephala) grown with maize showed that the trees had twice as many fine roots density as maize[43]. Such high root density in trees can favour trees over crops with regard to water and nutrient uptakes and therefore, corroborates the negative perceptions reported by the local people.Nevertheless, despite the negative perceptions, trees when grown together with arable crops have been shown to play many positive roles which favour arable crops as well. Trees do improve soil fertility; enhance water retention and regulate soil temperature all of which affect crop production[44, 45, 46, 47, 48]. Use of Azadirachta indica as windbreaks in Niger resulted in millet yield increase of 23%[9] while in Burkina Faso and Senegal planting of Acacia albida (Feidherbia albida) led to millet yield increases of 50%[4, 49]. Similarly a study to compare fields planted with trees and those without in Burkina Faso showed average yield increases in millet and sorghum production of 10% on fields with trees than those without[50].In some cases however, some of the respondents expressed the view that trees are “planted by God” and would therefore, prefer to have more open agricultural fields rather than fields dotted with trees. This belief was shown to have created difficulties in promoting baobab trees (Adanisonia digitata) which has multiple uses[48] and clear propriety user rights in Southern Niger[51]. The farmers perceived that these trees were divine gifts and growing them would imply tempering with divine courses of action (ibid.). Understanding such perceptions as held by the people provides opportunity for strengthening their capacities and to design appropriate sustainable forest activities involving their participation. Such perceptions may also be an indication that some of the community members have not identified benefits from trees and therefore, have paid less attention to forestry activities. This is a challenge which underscores the need for capacity strengthening to enlighten the communities about the values other than spiritual values associated with sustainable forest management.

3.3. Communities’ Perceptions on Forest Management

- The responses regarding local communities’ perceptions on current forest management practices instituted in the county and the impacts such managements have had on the forest resources are shown in Table 3. When asked about the specific consequences human activities have had on the tree resources, the respondents mentioned the impacts from extensive cutting of Acacia senegal and Acacia seyal for charcoal production and for firewood that has led to the reduction in cover of the said species; and instead, there have been increased cover of the landscape by the less valuable species of Acacia nubicans. Charcoal production is also a source of livelihood in South Sudan. It is made from the sparse tree resources of Acacia senegal and A. seyal considered to produce quality charcoal. The charcoal is sold in the urban markets in Renk and in Sudan. Wood collection for activities as charcoal making in such dry areas deplete the wood resources since the demand exceeds the natural regeneration[51, 39]. Acute fuelwood shortages affect about 112 million people in 18 African countries[52] and in the Sahel, nearly all trees on common and unprotected lands are harvested for the urban markets[53] perpetuating this depletion. In Sudan where 75% of the energy requirement is met by fuelwood (22 million m³ per year[54] this means that approximately 400 million acacia trees are cut annually[3] to meet this demand; leading to major land degradation as it strives to meet the quest for fuelwood[22].When asked what measures they would institute to increase tree cover, some of the respondents (Goz Fami, Sheikh Yasin and Abu Khadra) mentioned the following: tree protection from animals by engaging guards; and institute local bye-laws to safeguard tree owners whose trees may be damaged by animals by imposing fines and penalizing people found to mismanage the trees. The respondents mentioned the benefits of managing forest resources, particularly the Acacia seyal and A.senegal as being their value in gum production. This benefit can be an incentive to motivate the communities to engage in forest management as study elsewhere shows[31, 34] and be used as an entry point for strengthening the capacities of the communities on sustainable gum harvesting techniques.

|

3.4. Capacity Strengthening at Institutional Levels for the Enhancement of Sustainable Forestry

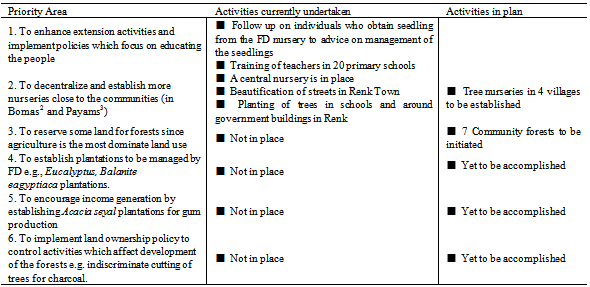

- This objective was accomplished by interviewing respondents in two institutions that carry out forestry education and development in Renk County namely the the University of Upper Nile (UNU) and Forest Department (FD) respectivelyWe sought to establish from the Forest Department (FD), the extent of forest cover in Renk County, and the department acknowledged that the forest cover is low but have plans to improve the situation as per some six priority areas (Table 4).

|

3.4.1. Current Extension Services in Renk

- The Forest Department (FD) had only two qualified personnel who were based in the County. There was one trained staff who together with some unskilled staff worked in the central nursery; while at the Boma level, (there are a total of 5 Bomas) there are forest guards who do not have any training in forestry but are employed to guard the forests. The staffing situation was not any better given that some of the qualified staff had attained retirement age and were likely to leave worsening the staffing challenge. Aging of qualified staff and disproportionate staff recruitment has been shown to affect agricultural productivity elsewhere in Africa[12] and in the same manner this is true for the case of FD in Renk. In addition, the department suffers from lack of adequate logistical support which exacerbates the problems in delivering extension services. As a result, the extension services offered by the Forest Department are limited to visiting and training individual community members particularly those individuals who obtain their seedlings from the Department’s central nursery. During such visits, advice is restricted to information related to planting and tendering techniques of seedlings. The other extension activities by the department are through campaigns which are conducted annually to encourage communities to plant trees. As explained earlier, in South Sudan, the seedlings are mainly obtained from the government run central nursery. This is a major setback for farmers who may want to intensify landuse by introducing trees on their farms. The disadvantages of reliance on the central nursery not only include logistical challenges but also that seedlings produced are not based on farmers’ needs but on perceived national and the FD’s policies and fail to address the community needs as typical in many regions[24]. Capacity strengthening therefore would enable the communities to raise their own tree seedling which would suit their needs and hence encompass sustainable forestry. Furthermore, communities would be empowered to have their own individual farmer’s nurseries which are known to produce more seedlings cumulatively and at lower costs than centralised nurseries such as group nurseries[56]. Despite the constraints of the FD, there are plans to establish 7 community forests (in Magara, Goz Famin, Geiga, Killo 5, Wagara and Killo 15, Gezira Bala) although 3 villages were not aware of such plans. In Magara, for instance, the respondents mentioned that land had been demarcated seven years earlier for the establishment of Acacia senegal plantation. The respondents did not mention having had contacts with the Forest Department personnel for any advice or support. However, some of the Sheikhs mentioned that they require extension services because many of the people in their communities are poor and need to interact with the extension services and to be educated to change their attitude towards being self reliant and to manage their environment. Other than information pertaining to tree planting, there were neither well defined technologies nor sustainable forest management related information that was being promoted by the FD during the study and the department mentioned specifically limitations of skills in handling many interventions. In particular, three aspects were mentioned in which the FD is limited and yet are affecting forestry development in the country. These were challenges on:a). Charcoal ProductionAs monetary economy increases in the county and communities begin to engage in petty trade[24], they are increasingly exploring other alternative sources of income and charcoal making is one such alternatives. Charcoal making in Renk County is poorly done with earth kilns which require more use of tree resources because of the low efficiencies of the kilns[8]. The consequence of this is the depletion of the few tree resources left in the landscape in order to produce enough charcoal for sale. Introduction of more efficient ways for charcoal production and selection of trees for charcoal making are some of the technologies and skills the FD can be imparted with in order to also build capacities of the communities who currently are not making the charcoal in any sustainable way. Wood fuel (i.e., firewood and charcoal) is still a major source of energy in Africa and cannot be dispensed with although as incomes improve, more people opt for other alternatives as LPG and electricity especially in the urban centres[57]. Despite the fact that the amounts of wood used as firewood or charcoal being similar due to higher efficiencies of charcoal stoves than wood stoves[61]; charcoal has an advantage over firewood because it has a higher calorific value (32-33MJ/kg) than firewood (18-19MJ/kg) and its production is necessary especially for the urban markets and income for the local communities[62]. The only drawback however, is the process of charcoal making in which losses ranging from 71-76% occur because of technologies used (e.g. earth kilns) especially in Africa[ibid.]. Since charcoal making uses forest biomass there is the risk that these resources can get depleted unless proper management is instituted[36] and such would include use of more efficient methods and technologies to improve charcoal making. In Africa, there have been proven technologies which improve yields by 45%[62] and such requires capacity building[61]. Encouraging and promoting alternative diversified plantation species or species producing less dense charcoal holds promise for sustainable charcoal making and use[ibid.) and can be incorporated in the capacity building.b). Inadequate Technologies for Gum Arabic HarvestingMany of the community members reported using fires to remove thorns from the Acacia seyal trees or removal of the barks from the trees to ease harvesting of gums both of which contribute to the degradation of the scarce tree resources and do not represent sustainable forest management. There are techniques that can be imparted to the FD staff to be able to train the gum tappers to ensure the trees are not adversely affected after gum harvesting. Use of an improved gum-harvesting tool locally called “sunki” for instance, may replace the traditional, inefficient harvesting techniques of making incisions into the tree with traditional small bladed axe. These older tapping methods do not yield the maximum amount of gum from the tree[63]. Damage to the wood should be minimal to produce superior quality product and such can be achieved through use of “sunki”. Adoption of improved gum-harvesting techniques may strengthen the rural economy and building sustainability[64] in the forest ecosystems upon which rural livelihoods depend.c). Wild FiresFires are used for management of pastures, however, in many cases in Renk, these fires spread out and burn areas not intended for such management. The consequences are that the few trees in the landscape are burnt out.[37] reported that range fires that are set intentionally for pasture improvement affect about 35% of the natural range productivity. Fires also affect ecosystem structures and function and result into changes in land surface. Therefore, whereas fires stimulate grass for fodder provision, alternative sources of fodder such as through forestry may be effective in controlling fires than using fire control techniques[49]. There are no skills in using prescribed fires as a tool in pasture management in Renk, although the FD indicated that there are plans to construct fire control measures of fire cut lines to control fire outbreaks. A strategy[59] that Forest department has is to hold discussions with the local Sheikhs to institute fire control measures including having to report incidences of fires to the department.

3.4.2. Forestry Education and Training

- The Upper Nile University has a campus located in Renk which offers training in forestry. During the study, linkages between the Forest Department and the University were explored, as well as linkage between the University and the local community with a view to establishing how forestry development is being conducted in the county. The responses received from both the department and the University was that there are no formal working relations between the two institutions except forwarding of relevant departmental reports to the university. The university’ relation with the Forest Department on the other hand is limited to the University supplying graduates into the labour market, some of whom may or may not be absorbed by the Forest Department.[4] underscores the need for partnership and collaboration between stakeholders to enhance research and development. Therefore, there can be immense mutual benefits for both institutions for the development of forestry in the county if these two institutions collaborated[53].Through collaborations, many aspects of capacity strengthening for both institutions can be achieved. During the discussions with respondents from both institutions, specific areas of collaboration between the department and the University were highlighted and these were that: Upper Nile University (UNU) staff could provide in-service training to the Forest Department staff; generate and develop technology through research on issues identified by the department regarding sustainable forestry (e.g. fire control and management, gum tapping and charcoal production) that they lack skills in. UNU could generate, develop and undertake adaptation trials on technologies as use of trees and shrubs for soil fertility enhancement in the demonstration farm which can also be used for extension. The Forest Department on the other hand could assist the University to assign students to undertake outreach activities among the communities on various aspects of forest management. Collaboration between UNU and the communities was also explored. It was reported however, that this collaboration existed in the past with communities in Malakal, the State’s capital through local media. This is a practice yet to be introduced in Renk to complement the Forest Departments’ campaigns especially to highlight seasonal messages such as tree planting or gum tapping that can be undertaken only during certain seasons. Dissemination activities in any form have significant positive influences on both research and development[66]. It is through dissemination that new information from research can reach the target audience and to enhance their capacities to implement the ideas. In Renk, dissemination activities are limited and needs to be expanded beyond the media. UNU could be encouraged to undertake other outreach programmes and field visits through students’ attachments who would work and share their knowledge and skills with the farmers. Currently, UNU has a demonstration farm where different trials are established and monitored. This is an infrastructure which the UNU can use to reach the farmers when they attend field days to observe new technologies that have been successfully tried. The field days would offer the communities the opportunities to observe and choose which technologies to adopt and for the University to engage with communities to identify capacity gaps and therefore, to respond by establishing research to address the communities’ needs[18].

3.5. Areas of Investment for Future Strengthening Capacity for Sustainable Forestry

- While at times the local communities are assumed to lack capacities or knowledge to manage forests,[67] suggests that this is not always true because in such cases, the communities may not share the same objectives as those institutions promoting forest management. In the case of Renk however, we established that capacity gaps were the case. We also established the desire by the communities to engage in forest management and as had been observed by[68] in Mali. We also found that the local communities in Renk have different perceptions about forest resources and their management, and are willing to participate in forest management. Responses from SWOT analyses about the implementation of forestry extension services are shown in Table 5. We also established the limited capacity of the Forest Department to deliver forestry extension services to the communities despite the desire by the communities to be trained.[65] also found that the communities in Renk desire to be provided with training and extension services on forestry. To address this gap, the Forest Department should increase coverage and attain good depth of reach in the communities by using selected community members as resource persons. The community resource persons would be trained centrally by the Department regularly to reduce logistical hardships while maximising on the limited staff. In turn, the trained Community Resource Persons would train and work with communities to promote sustainable forestry. In many development programmes, the use of local communities as resource persons is a common phenomenon. Such persons are often selected by the communities therefore, they are trusted and have the potential to influence the community to willingly adopt innovations as has been the case in India[69] and Haiti[70] . When local persons are used to provide extension services, it reduces the risk of the information reaching only the local people with economic power who are often favoured and perceived to readily adopt innovation and therefore provided with the extension services[71]. Therefore, local persons are community members who share similar socio-economic background and therefore, interact readily with many of the peers. The SWOT results and the responses showed that there is a need to provide capacity building to the Forest Department as well as the communities. In particular, capacity building for the Forest Department will enable the FD to carry out effective extension services to the communities. The major setback of inadequate technical capacities by the Forest Department can also be improved through collaboration with the UNU. This will enable UNU to provide regularized in-service trainings to the unskilled FD staff in thematic areas to address the needs of the communities with regard to sustainable forest management including technological gaps that have been identified by the FD. Such trainings would create a critical mass of skilled trainers at the department who would in turn train the community resource persons to be able to train the rest of the community members.

|

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Sustainable forest management is currently not being practiced in Renk on account of inadequate capacities of forestry institutions and the communities. Consequently there is continuous pressure on the remaining limited forest resources, resulting in degradation and further depletion of the resources. There is however, scope and justification to increase forest resources in Renk due to the interest of the communities as well as from the Forest Department. Trees are among the source of income for livelihood for the people of Renk County. However, the multiple challenges affecting the sustainability of these resources require comprehensive approach in instituting effective plans for sustainable forest management. As a first step, unsustainable practices that deplete forest resources (wild forest fires, inefficient charcoal production, unsustainable gum harvesting) can be addressed through provision of appropriate technologies. This can be achieved through capacity strengthening from sound training and research-extension-farmer linkages. Such capacities will introduce new skills and appropriate technologies to be used. Thus, there is need to utilize and strengthen existing capacities of both the department and the communities to create synergy for sustainable forest management in Renk County.

Note

- 1. 1 Feddan=0.42 ha

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML