-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2013; 3(4): 138-140

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20130304.02

Use of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Grown on Different Substrates (Wheat and Barley Straw) and Supplemented at Various Levels of Spawn to Change the Nutritional Quality Forage

Mehdi Dahmardeh

Department of Agronomy, University of Zabol, Iran

Correspondence to: Mehdi Dahmardeh, Department of Agronomy, University of Zabol, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The effect of Pleurotus ostreatus on the chemical composition of wheat and barley straw were evaluated. Wheat and barley straw, treated with Pleurotus ostreatus, were obtained from a library. Field experiment was conducted at college of agriculture, Zabol University during 2010- 2011 growing season. Experiment was carried out as factorial and based on CRD design with three replications. Factors were different substrates (Wheat and Barley straw) and various levels of Spawn (50, 70, 90, 110, 130, 150 and 170 g/bag). All samples were analyzed to determine dry matter (DM), Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Ash and Mushroom yield of wheat and barley straws. Data were analyzed by mean comparison using a Least Significant Range (LSR). No differences (P>0.05) between treatments were found for dry matter and NDF at between substrates. No significant different between levels of spawns for Dry Matter but significant different between Ash and NDF for levels of spawns and Ash for between substrates (P≥0.01). It is concluded that growing Pleurotus ostreatus in wheat and barley straws improves the chemical composition of the straws by increasing its Ash content and decreased the NDF structure with increased levels of spawns. Maximum yield (weight of fresh mushrooms harvested at maturity) was obtained on Barley straw substrate (1388.3 g/2kg wet substrate) at 150 g/bag spawn level (1494.7 g/2kg wet substrate).

Keywords: Chemical composition, Substrates, Neutral Detergent Fiber, Yield Mushroom

Cite this paper: Mehdi Dahmardeh, Use of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Grown on Different Substrates (Wheat and Barley Straw) and Supplemented at Various Levels of Spawn to Change the Nutritional Quality Forage, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 138-140. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20130304.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Mushrooms are becoming a popular crop among small scale farmers in the country due to favorable prices and the increasing demand from consumers. Mental maturity of mushrooms is easy because the farmer only necessity crop residues which are abundant on the farm. A number of institutions in the country are currently producing seeds (spawn) for farmers. Mass production of oyster mushroom first started in the last 1960[8], using a stem based substrate[3]. Commercial production techniques for this food basidio mycete are good developed[14]. Compared to other edible Mushrooms, species of Pleurotus are relatively simple to cultivate[16]. Biological agents have been used to increase digestibility of small quality forages (Montaez et al., 2004). Akinfemi et al (2010) were reported that the biodegradation of sorghum Stover using two different fungi resulted in increased crude protein (CP) and decrease in the CF breaking with the consequent result on increase in the digestibility of the substrates[1]. The use of fungi or their enzymes that metabolize lignocelluloses is a potential biological treatment to betterment the nutritional valuation of straw by election delignification[8]. Ortega et al (1986) observed a deduction in neutral detergent fiber concentration at 45 and 65 days after incubation of barley stem with P. ostreatus[10]. Some tests of the agricultural damages studied as substrates for Pleurotus spp. are coffee industry residues[7], coffee pulp and wheat stem[11], lost paper[2]. The substrates used in each region depend on the locally available agricultural lost[6]. This study was therefore conducted to investigate the improvement in the nutritive value of wheat and barley straw after treated with Pleurotus ostreatus.

2. Material and Methods

- The research project was conducted in the Agriculture College, Department of Agronomy, University of Zabol., during the 2010- 2011 growing season. The filed experiment was carried out on the university of Zabol Farm , in Sade- Sistan (61◦ 41′E, 30◦ 54′N, altitude 483 m above sea level), of Iran. The substrates were soaked in water for 24 hours to moisture them thoroughly were stalked on the steep cemented floor so as to remove the excessive moisture from the substrates to get 65- 75 % moisture level. The bags were autoclaved at 121◦ at 15- 20 lbs pressure and allowed to cool. After sterilization next day the bags were inoculated with the spawn of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). The bags were than inoculated for spawn running under complete darkness at controlled temperature of 25℃. The temperature was controlled by electric heaters 25℃ for spawn running and 17- 20℃ for fruiting body formation. The humidity of bags was accomplished by spraying of water on them three a day. The experiments were designed as 2 substrates (Wheat and Barley straw) × 7 spawn levels (50, 70, 90, 110, 130, 150 and 170 g/bag) factorials in CRD with three replications. The SAS program was used to analysis data[12]. The Least Significant Range was used to separate treatments means. Samples were ground in a Wiley mill using a 1mm screen, and then analyzed for dry matter (DM), Ash and Neutral detergent fiber were determined according to Near Infrared spectrophotometer (NIR).

3. Results and Discussion

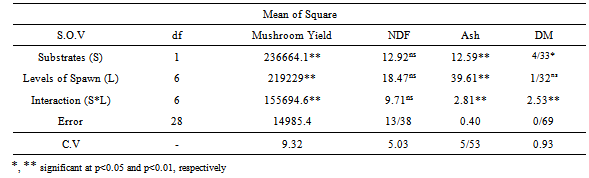

- The results of analysis variance the chemical composition and Mushroom yield of the treated wheat and barley straws are shown in Table 1.

3.1. Yield of Mushroom

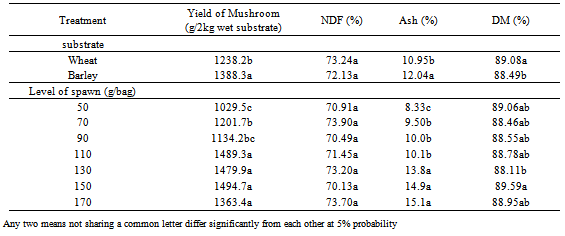

- Significant different of variation in the analysis of variance for yield for substrates, level of spawn and interaction substrate and level of spawn (Table 1). Maximum average yield 1388.3 (g/2kg wet substrate) was estimated from the Barley substrate compared to wheat substrate 1238.2 (g/2kg wet substrate) (Table 2). So recommended as a best substrate for the cultivation of oyster mushroom is Barley substrate. For both substrate types, increasing levels of spawn levels resulted in yield increased (Table 2). The best of level of spawn for yield was obtained at 150 g/bag spawns (1494.7 g/2kg wet substrate) that no significant different to 170 g/bag. Smita (2011) was showed that the highest biological efficiency was obtained with 8 percent and there was no significant difference in yield with 6, 8 and 10 percent spawn doses[13]. The increased rate of spawning speeding colonization narrowed the gap of opportunity for competitor invasion, and significantly improvements yields[14].

|

|

3.2. Nutritional Quality of Substrates

- Ash was significantly affected by supplement level of spawn and substrate (Table 1) but DM of was just significant different at substrate and no significant different at level of spawn. The variation of NDF no significant different at both factors. The highest of NDF was obtained at wheat straw (73.24%) and 70 g/bag spawn (73.9%) that no significant different with other treatments. The lowest of NDF was obtained at barley straw (72.13%) and 150 g/bag level of spawn (70.13%). The highest of Ash was obtained at barley straw (12.04%) and 150 g/bag spawn (14.9%) that significant different with other treatments. The lowest of Ash was obtained at wheat straw (10.95%) and 50 g/bag level of spawn (8.33%). The highest of DM was obtained at wheat straw (89.08%) and 150 g/bag spawn (89.56%) that no significant different with 110 g/bag. The lowest of DM was obtained at barley straw (88.49%) and 130 g/bag level of spawn (88.11%). Chang and Buswell (1996) were showed that nutrient content of substrates affect the formation of fruit bodies[4]. Also Zadrazil (1980) was shown that growth of Pleurotus species is beneficial on substrates of low nitrogen amount, that is, higher carbon and nitrogen ratio to raise good yield[17]. Chen (1998) was reported that the total nitrogen content in the sawdust waste increased 10% over pre-cultivation for mushroom cultivation[5]. Wanapat et al (2009) were shown that treating rice straw with urea or calcium hydroxide or by supplementing rice stem with protein, intake, degradability and milk yield can be improvement, compared to feeding untreated rice straw sole[15]. The proximate composition of fungal treated barley and wheat straw presented in this study showed that changes in the Ash and NDF contents compared favorably with those study fungal treated residues that agree with other researchers[1]. Fungal treatment increased the Ash contents of the barley and wheat straw. Fungal treatment of barley straw not only improved the Ash contents but also enhanced digestibility via decrease of NDF. To seem the use of fungi improve the feed value of barley and wheat straw. To achieve optimal feed qualities of the barley and wheat straw, incubations with fungi have to be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The author wish to thank of Mehdi Ghaeni and Reza Amiri for technical assistance.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML