-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2013; 3(4): 129-137

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20130304.01

Factors Enhancing Effective Management of Household-based Enterprises in Osun State, Nigeria

D. L. Alabi1, A. J. Farinde2, G. E. Ogbimi3, K. O. Soyebo3

1Osun State Agricultural Development Programme, Iwo. Nigeria.

2Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, ObafemiAwolowo University,Ile-Ife. Nigeria.

3Department of Family, Nutrition and Consumer Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture.ObafemiAwolowo University, Ile-Ife. Nigeria

Correspondence to: D. L. Alabi, Osun State Agricultural Development Programme, Iwo. Nigeria..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The paper identified crucial factors enhancing effective management of rural household-based enterprises in Osun State, Nigeria. A multistage sampling procedure was employed in selecting 400 rural entrepreneurs in 9 Local Government Areas of the State. Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed to analyze the data. Results revealed that the mean age of enterprises’ owners was 45.15 years, the mean capital investment was N29,500, mean monthly income was N17,100 and mean years of experience was 17.7 while 20 enterprises were identified with cassava processing and palm oil production being the most common. Eleven crucial factors were isolated with 62.6% contribution to effective management of rural household-based enterprises in Osun State. These included enterprise survival traits, personal experience, enterprise characteristics, social contact influence, institutional roles and length of apprenticeship training. Others include household strength, economic influence, community assets, cultural compatibility and form of involvement in the enterprise. In conclusion, the growth and development of the identified rural enterprises depend largely on these factors

Keywords: Household-Based Enterprises, Rural, Effective Management

Cite this paper: D. L. Alabi, A. J. Farinde, G. E. Ogbimi, K. O. Soyebo, Factors Enhancing Effective Management of Household-based Enterprises in Osun State, Nigeria, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 129-137. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20130304.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Household-based enterprises constitute the non-farm sector of rural economy.[1] defined non-farm as those activities that are not primary agriculture or forestry or fisheries but include trade or processing of agricultural products even if they take place on the farm. The term “non-farm” should not be confused with “off-farm”. The latter generally refers to activities undertaken away from the household’s own farm.[2] used the term “off-farm” to refer exclusively to agricultural labouring on someone else’s land.[3] defined household enterprises as the first unit of micro-entrepreneurship, the family firms or the non-farm businesses that could potentially grow into small or medium enterprises; and as trades passed down over generations and a special category of tiny businesses that work on the basis of family ownership and labour.[4]opined that they are the countless tiny businesses begun by the poor in the cities, town, and villages of the developing world, such as mechanics in “shade-tree” shop and tailors in their living rooms.These enterprises play significant roles in the overall economic growth of a nation. For instance, in the United States, more than 90 per cent of the 15 million businesses are family owned and controlled[5]. Also, between 30 and 60 per cent of the gross national product was contributed by family businesses[6]. They also help to develop the rural non-farm sector by absorbing surplus labour in rural areas (rather than migrating to towns and cities, individuals not absorbed in agricultural work and having some wherewithal try to build on household enterprises); promote indigenous entrepreneurial capabilities; and employ a sizeable proportion of the working population in several developing countries. For example, in India, they constitute 11 per cent of the total workforce. In addition, they help farm-based households to spread risks; offer more remunerative activities to supplement or replace agricultural income; offer income potentials during the agricultural off-seasons; provide a means to cope or survive when farming fails; provide the cash that enables farm households to purchase food during drought or after a harvest shortfall; serve as farm household source of savings used for food purchase in difficult periods thereby enhancing farm household food security; conserve scarce managerial abilities; introduce vital skills into rural areas; and utilize valuable but scattered pockets of rural resources that might otherwise go to waste e.g. nuts and seeds for oil processing, wood for furniture and charcoal production[3];[1] and[7].The number of people involved in various non-farm activities form a large share of those employed outside agriculture in most African countries. For instance in Zambia, 25,000 people were involved in the fuel wood trade[8], 48,000 people were employed in charcoal production, 11,500 people involved with bee-keeping and 96,000 households earn income from handicraft production[9]. Also in Cote d’Ivoire, about 65,000 people were involved in rattan cane basketry[10].Rural households in Nigeria also engage in various forms of non-farm enterprises as a survival or a coping strategy to eke out a living for themselves. According to[11], these activities include pottery, weaving, carving, carpentry, bicycle-repairing, black smithing, dyeing, dressmaking, retailed trading, barbing and hair dressing, drinking parlour operation, bricklaying, native doctoring, among others.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

- In Nigeria and Osun state in particular, rural households engage in various household based enterprises which provide employment and income for a substantial percentage of them particularly during agricultural off-seasons and seasonal short falls in food and cash crop income as well as in periods of draught or emergencies. The growth and development of the rural enterprises in terms of transforming the rural economy for better remain stagnant because the precursors of effective management have not been identified. This is because research efforts have not being geared towards identifying the factors associated with the effective management of these enterprises. Unless these factors are identified, growth and development of these enterprises would remain impaired.

1.2. Objectives of the Study

- The main objective of the study is to identify factors enhancing effective management of rural household-based enterprises in Osun state, Nigeria. Specifically, the study:1. identified type of rural household-based enterprises in the study area.2. examined socio-economic characteristics of their owners; and3. isolated factors enhancing their effective management.

2. Methodology

- The study was conducted in the three Osun State Agricultural Development Programme (OSSADEP) zones namely Ife/Ijesa, Iwo and Osogbo with ten, seven and thirteen Local Government Areas (LGAs), respectively. A multistage sampling procedure was used to select the respondents. One-third of the LGAs from each zone were randomly selected at the first stage, 30 communities were proportionately sampled from the selected LGAs at the second stage while 3 percent of the population of each of the selected villages were randomly selected at the third stage to make a total of 400 respondents in all. Pretested and validated interview schedule was used to collect data based on the objectives of the study. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data.Descriptive statistics include frequency counts,percentages, means and standard deviation while factor and component analyses were used to isolate crucial factors that are contributive to effective management of rural household - based enterprises.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Socio-economic Characteristics of Entrepreneurs

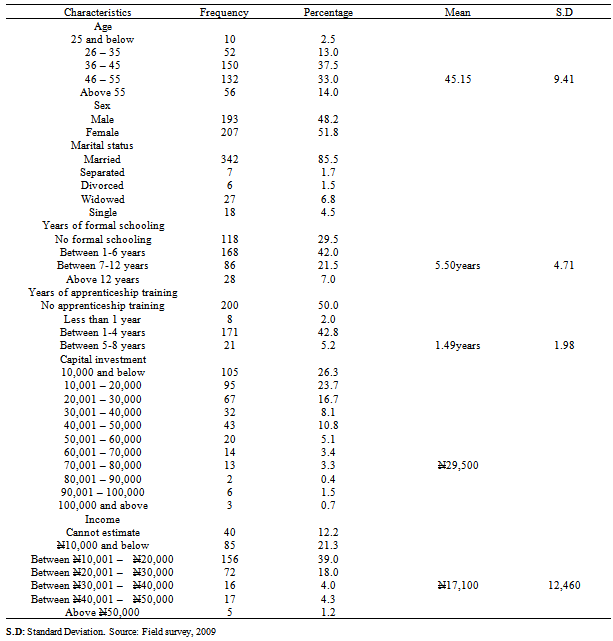

- The socio-economic characteristics of the respondents are presented inTable 1. The mean age was 45.15 years. This implies that majority of owners of these enterprises were still in their active ages when they could still make significant contribution to the development of rural entrepreneurship if necessary resources were made available. Age is one of the factors that could be used to measure people’s level of maturity, strength and ability to accomplish. Active ages are characterized with hard work and relentless efforts to achieve, as against old age when little or nothing could be accomplished. Entrepreneurs who are in their active ages are more likely to manage their enterprises more effectively than the aged. About 52 percent of the respondents were female while the remaining 48.2 percent were male. The higher percentage of females could imply that the studied enterprises favour the female gender. This is in conformity with[12] which confirmed that women were found largely in small enterprises like trading, food processing, dress making, soap making, cloth weaving and cloth dyeing while men were found in more lucrative activities.A large number (85.5%) of the respondents were married, few (1.7%) were separated, very few (1.5%) were divorced, some (6.8%) were widowed and 4.5 percent were single. As a result of family responsibilities and commitments of married people, they are likely to be more responsible and more committed to their enterprise success to enhance their household members’ welfare than the unmarried. The finding agrees with[13] which established a positive relationship between marital status and business performance which is an indicator of effective management.Some (29.5%) of the respondents had no formal education, many (42.0%) spent between 1-6 years in school while only 28.5 percent spent more than 6 years in school. The mean year of schooling was 5.5 years implying that the sample studied had a low standard of education. The result conforms to[14] which reported that 29.7 percent of rural households in Osun State had never been to school and 6.6 years as their mean years of schooling. Attendance of formal school provides opportunity for enlightenment and exposure in various areas of life. An entrepreneur who is highly educated is likely to be more enlightened in enterprise administration than the illiterates or those with low level of education.Half (50.0%) of the respondents had no apprenticeship training while the remaining half had between 1-8 years of training. The mean years of apprenticeship training was 1.49 years with1.98 standard deviation. Apprenticeship training is an indigenous way of skill acquisition among local entrepreneurs. The fact that half of the sample studied indicated that they had no apprenticeship training may imply that most of the studied enterprises were inherited from previous generations; hence no formal apprenticeship training was involved.The capital investment of most enterprise owners in the study area was relatively low with mean capital investment of N 29,500.This observation may be an indication that their credit sources were mainly internal and the need for the intervention of micro finance institutions in provision of more adequate credit opportunities for rural entrepreneurs. Few (12.2%) of the respondents could not estimate their monthly income from their enterprises while the mean income was N17, 100 per month. The inability of some of the respondents to give the estimate of their monthly income may be due to their inability to keep proper record of their income or their deliberate refusal to disclose the amounts they actually realized for fear of taxation and security reasons. The mean monthly income of

17,100; at 150 Nigerian Naira (NGN) = 1United State Dollar (USD) equals $114.00 monthly income. This is higher when compared with monthly income of

17,100; at 150 Nigerian Naira (NGN) = 1United State Dollar (USD) equals $114.00 monthly income. This is higher when compared with monthly income of  500 reported by[15] among entrepreneurs engaging in cloth weaving, mat, soap and pottery making in Southwestern Nigeria at 78.5 NGN = 1USD. It shows a significant improvement in the earnings of small enterprise owners over the years in Southwestern Nigeria.

500 reported by[15] among entrepreneurs engaging in cloth weaving, mat, soap and pottery making in Southwestern Nigeria at 78.5 NGN = 1USD. It shows a significant improvement in the earnings of small enterprise owners over the years in Southwestern Nigeria.

|

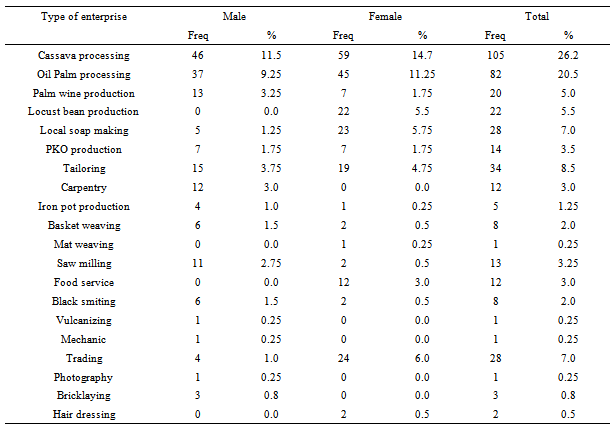

3.2. Rural Enterprises

- Table 2 presents identified small rural enterprises. It shows that cassava processing (26.2%) and oil palm production (20.5%) were the most common household-based enterprises in the study area and women were more in these enterprises than men. The implication of this is that efforts to develop rural household–based enterprises in the study area should focus these common enterprises. The result conforms to[16], which reported that cassava processing constitutes one of the major agro-industrial activities in Nigeria with more than half of Nigeria’s economically active women engaging in it.

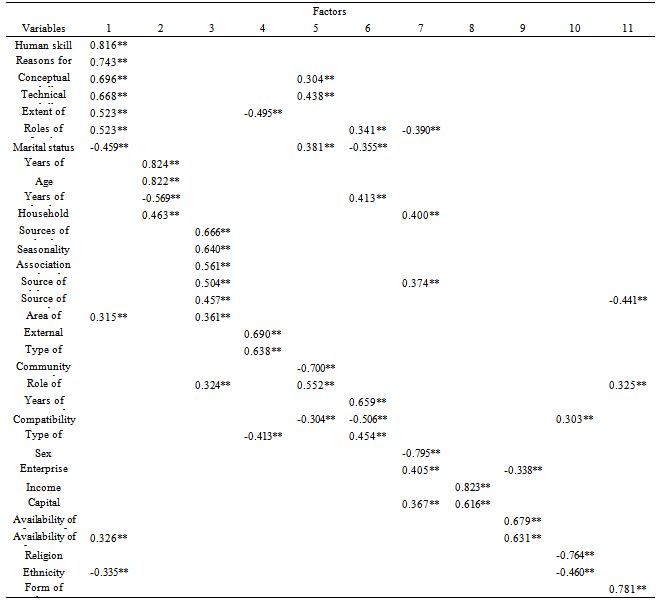

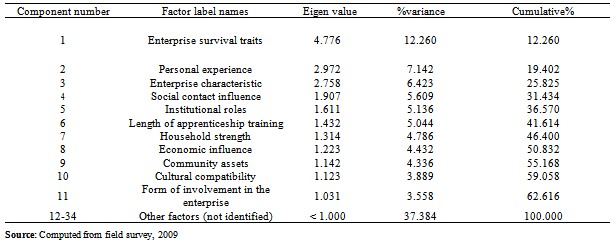

3.3. Factors Contributing to Effective Management of Rural Enterprises

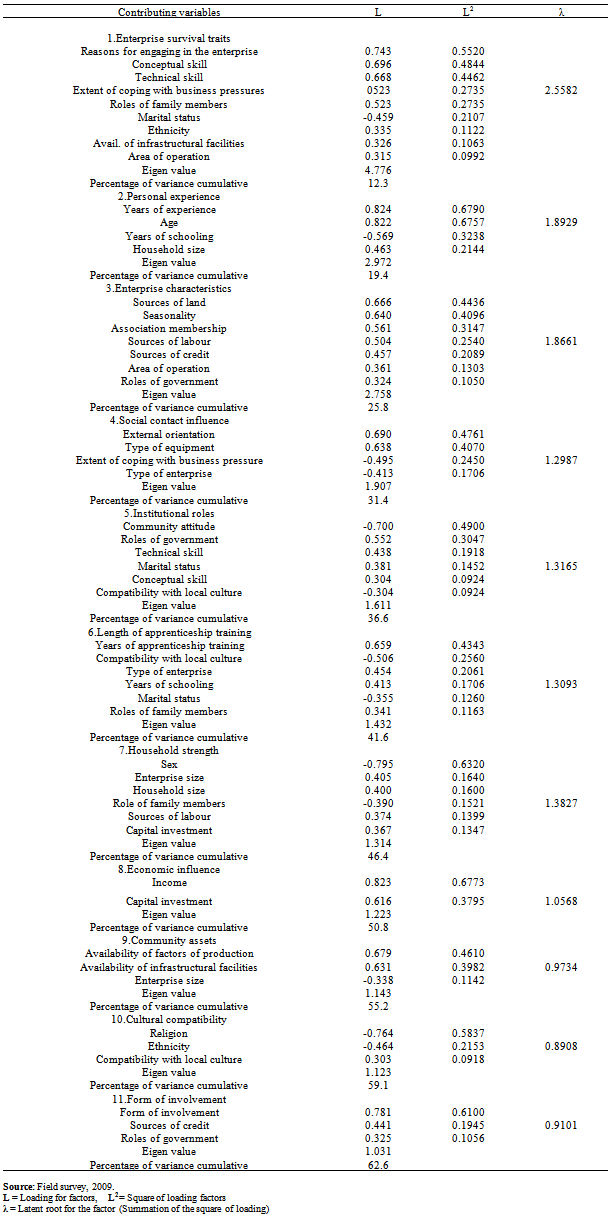

- Table 3 shows the results of varimax factor rotation pattern with the measures that were highly loaded on each of the eleven factors extracted. Out of the thirty-four variables listed, the loading which gives Eigen value of greater than one were eleven in number. Table 4 shows that the factors loaded explained 62.6 percent of variance in all while unknown factors explained the remaining 37.4 percent of the variance. The contribution of each of the highly loaded factors to change in effective management of rural household - based enterprises were also shown as follows: Factor 1 – enterprise survival traits was mostly associated with effective management with 12.3 percent contribution, followed by factor 2 – personal experience (7.1%), factor 3 – enterprise characteristics (6.4%), factor 4 –social contact influence (5.6%), factor 5 – institutional roles (5.1%), factor 6 – length of apprenticeship training (5.0%), factor 7 – household strength (4.8%), factor 8 –economic influence (4.4%), factor 9 –community assets (4.3%), factor10-cultural compatibility (3.9%) and factor 11 – form of involvement in the enterprise (3.6%).

3.4. Rules of Decision

- The factors retained were named based on the following criteria as employed by[17] and 18.a. The researcher’s subjective interpretation of experiences from literatures.b. Picking synonyms of the highest loaded variable on each factor.c. Retaining the name based on the similarity of the features of the variables contributing to each factor.d. Joint explanation or interpretation of the meaning of the positive and highly loaded variables on each factor.Table 5 shows the measures of loading of each of the eleven factors isolated and the percentage contribution of each of them to effective management of rural household - based enterprises.

|

|

|

3.4.1. Factor 1: Enterprise survival traits

- This factor was defined by eleven measures of loading out of which nine were positively loaded. These were human skill (L=0.816), reasons for engaging in the enterprise (L=0.743), conceptual skill (L= 0.696), technical skill (L=0.668), extent of coping with business pressure (L=0.523), roles performed by family members (L=0.523), availability of infrastructural facilities (L=0.326) and area of operation (L = 0.315). The factor was named based on criteria three and four. The findings imply that the survival of an enterprise will depend largely on the managerial capabilities of owners, importance of the reasons why the owner engage in it and ability of owners to cope with diverse business pressures. Household members and the government must also perform their respective functions while market opportunities should be extended beyond the local areas.

3.4.2. Factor 2: Personal experience

- The factor was identified by four measures of loading out of which three were positively loaded. They include years of experience (L=0.824), age (L=0.822) and household size (L=0.463). Criterion two was employed to name the factor. The active age and work experience of an enterprise owner were germane to enterprise success.

3.4.3. Factor 3: Enterprise characteristics

- This factor was defined by seven measures of loading that were all positively loaded. These were sources of land (L=0.666), seasonality (L=0.640), association membership (L=0.561), sources of labour (L=0.504), sources of credit (L = 0.457), area of operation (L = 0.361) and roles of government (L = 0.324).This factor was named based on criteria one, two and three. The peculiar characteristics of an enterprise particularly its sources of obtaining major factors of production such as land, labour and credit as well as seasonality and area of operation would determine its mode of operation and consequently, how effectively it would be managed

3.4.4. Factor 4: Social contact influence

- The factor was identified by four measures of loadings out of which two were positively loaded. These were: external orientation (L=0.690) and type of equipment (L=0.638). Criterion two was used to name the factor. The extent of cosmopolitan of an enterprise owner could influence his/ her choice of enterprise equipment and consequently, the effectiveness of operations.

3.4.5. Factor 5: Institutional roles

- This factor was defined by six measures of loading out which four were positively loaded. These were: roles performed by government (L=0.552), technical skill (L= 0.438), marital status (L=0.381) and conceptual skill (L= 0.304). This factor was named based on criteria two and four. It implies that when government institution performs its expected roles, particularly, in building the capacity of owners of rural household-based enterprises, it will foster effective management and appreciable development.

3.4.6. Factor 6: Length of apprenticeship training

- The six measures of loading that defined this factor and four that were positively loaded among them. They were: years of apprenticeship training (L=0.659), type of enterprise (L=0.454), years of formal schooling (L=0.413) and roles of family members (L=0.341). Criteria two and four were employed to name the factor. The nature of an enterprise together with the trainee’s literacy level will determine the length of period to be spent in learning the job. The measure of the skill acquired in training would influence the level of effective enterprise management.

3.4.7. Factor 7: Household strength

- This factor was defined by six measures of loading out of which four were positively loaded. They were: enterprise size (L = 0.405), household size (L = 0.400), sources of labour (L = 0.374) and capital investment (L = 0.367). Criterion four was used to name the factor. It implies that the ability of households to invest adequate capital resources and man power will enhance enterprise size and more specialized operation.

3.4.8. Factor 8: Economic influence

- Income (L= 0.823) and capital investment (L= 0.616) were the two measures of loading that identified this factor. Criteria two and three were employed to name the factor. Realizing adequate income from an enterprise could encourage more investment in the enterprise.

3.4.9. Factor 9: Community assets

- This factor was defined by three measures of loading out of which only two were positively loaded. These were: availability of factors of production (L= 0.679) and availability of infrastructural facilities (L=0.631). Criteria three and four were used to name the factor. Availability of productive and infrastructural assets in the community could minimize seasonal challenges and business pressures facing rural household-based enterprise. It could also account for the reason why people engage in their selected enterprises. The roles of the government in making these assets available cannot also be over emphasized.

3.4.10. Factor 10: Cultural compatibility

- Compatibility with local culture (L = 0.303) was the only positively loaded measure out of the three measures of loading that identified these factor. Criterion two was used to name the factor. Enterprises that are compatible with existing culture will foster effective management.

3.4.11. Factor 11: Form of involvement

- This factor was defined by three measures of loading out of which two were positively loaded. These were: form of involvement in the enterprise (L=0.781) and roles of government (L = 0.325). Criteria two and four were used to name the factor. Rural households will be more actively involved in these enterprises when the government puts in place relevant strategies that could stimulate their interest.These crucial factors identified in the study are the determinants of effective management of household-based enterprises in the study area. They indicate the important aspects of these enterprises that must be well focused to enhance their growth and development.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Conclusions and recommendations

- The study yielded results that have policy implications for promoting rural entrepreneurship, employment and income generation among rural households especially during agricultural off-seasons. Policy measures and research - extension efforts to develop non-farm economic activities in the rural areas should be directed toward cassava processing and oil palm production which were the most common non - farm household-based enterprises in the study area. The fact that women were more in these enterprises than men showed that the needs and constraints of female entrepreneurs should be given topmost priority.Entrepreneurs in the age bracket of 25 and 55 years constituted the majority; hence developmental efforts should target this age group. The low standard of education and inadequate apprenticeship training observed among enterprise owners showed the need to seriously emphasize adult literacy programme and introduction of relevant indigenous apprenticeship package to enhance adequate skill acquisition. The low capital investment also indicated the need for the intervention of microfinance institutions in the provision of more adequate credit opportunities for rural entrepreneurs.For effective management of these enterprises, owners should properly operationalize the crucial factors isolated in the study that were found to be highly associated with their growth and development.

References

| [1] | Gordon, A. and Craig, C. (2001).Rural Non-farm Activities and Poverty Alleviation in sub-Sahara Africa. Policy Series 14, Chatham, UK: Natural Resource Institute pp. 1-37. |

| [2] | Ellis, F. (1998). Survey Article: Household Strategies and Rural Livelihood Diversification. Journal of Development, 35 (1): 1-38. |

| [3] | Maitreyi, B. D. (2003). Social Protection Discussion Paper. The Other Side of Self-employment: Household Enterprises in India. http://www.wordbank.org/sp.pp1-30. |

| [4] | Adelante Foundation (2006). What is micro enterprise? |

| [5] | http://www.adelantefoundation.org/microenterprise.htm.p.1 |

| [6] | Ibrahim, A. B. and Ellis, W. H. (1994). Family Business Management: Concept and Practice. Dubuque, IA. Kendall Hunt. In Winter, M. and Morris, E.W. Family Resource Management and Family Business: Coming Together in Theory and Research, p.4. |

| [7] | International Family Business Programme Association (IFBPA), Task Force (1995).Family Business as a Field of Study. Family Business Annual, 1(Section 11), 1-8. |

| [8] | Arnold, J.E.M. (1994). Nonfarm Employment in Small-scale Forest-based Enterprises: Policy and Environmental Issues. Working Paper No. 11, 49pp. |

| [9] | Fisseha, Y. and Milimo, J. (1986). Rural Small-scale Forest - based Processing Enterprises in Zambia: Report of A 1985 Pilot Survey.FAO of the United Nations, FO: MISC/86/15. Rome, Italy. In Arnold, J. E. M. Nonfarm Employment in Small-scale Forest-based Enterprises: Policy and Environmental Issues. Working Paper No. 11, p. 10. |

| [10] | Marks, S. and Robbins, R. (1984).People in Forestry in Zambia.FAO of the United Nations, Forestry Department, Rome, Italy. In Arnold, J. E. M. Nonfarm Employment in Small-scale Forest-based Enterprises: Policy and Environmental Issues. Working Paper No. 11, p.10. |

| [11] | Kaye, V. (1988). Etude SurlesPotentialites De L’artisanat D’art En cTeD’ivoire: Plan Triennal De Developpment De L’artisanat D’art. Cote d’ivoire: Sous Direction. In Arnold, J. E. M. Nonfarm Employment in Small-scale Forest-based Enterprises: Policy and Environmental Issues. Working Paper No. 11, p.10. |

| [12] | Ekong, E.E. (2003). An Introduction to Rural Sociology 2nd Edition. Dove Educational Publishers, Uyo, Nigeria, pp. 187-189, 377-379. |

| [13] | Ogunrinola, I.O. (1990). Employment and Earnings in the Urban Informal Sector of Ibadan. In Afonja, S. and Aina, B. (eds.) Nigerian Women in Social Change, ObafemiAwolowo University Press Limited, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.p.123. |

| [14] | Fielden, S.L., Davidson, M.J. and Makin P.J. (2000). Barriers Encountered During Micro and Small Business Start-up in North-West England. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 7, No. 4. |

| [15] | Soyebo, K.O. (2005). A Study of Rural Household Resource Management in Osun State, Nigeria. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, ObafemiAwolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, p 184. |

| [16] | Aina, O.I. (1995), "Technological Assimilation in Small Enterprises Owned by Women in Nigeria" in Osita M. Ogbu, Banji O. Oyeyinka, and Hasa M. Mlawa (eds.) Technology Policy and Practice in Africa, Ottawa, Canada: IDRC pp. 165 - 179. |

| [17] | Oboh, G. and Ajomale, K. (2006): Management of Occupational Hazards Associated with Traditional methods of cassava processing in Ogun, Ondo and Oyo States, Nigeria. In Omueti, O. (ed.) proceedings of a workshop on promotion of improved Management Technologies aimed at Reducing Occupational and Environmental Hazard Associated with Traditional cassava processing in Osun, Lagos and Edo States, Nigeria, p.13 |

| [18] | Farinde, A.J. and Jibowo, A.A. (1996).Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of the Training and Visit Extension System in Lagos State, Nigeria. In Adesimi, A.A., Alao, J.A., Okusami, T.A., Aderibigbe, A.O., Ajobo, O. and Obisesan, I.O. (eds.) Ife Journal of Agriculture., 18 (1 & 2), 10 -25. |

| [19] | Ajayi, O.A. (2002). Development of Small Scale Industries in Nigeria. In AdegbiteAdegbite, S.A.; Ilori, M.O; Irefin, I.A.; Abereifo, I.O. and Aderemi, H.O.S (eds.) “Evaluation of the impact of Entrepreneurial Characteristics on the Performance of Small Scale Manufacturing Industries in Nigeria”. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, 3(1), 2 -22. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML