Oluwemimo Oluwasola

Department of Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile- Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oluwemimo Oluwasola , Department of Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile- Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The study examined the prospects of integrating small holder food crop farmers in the new government policy drive for enhancing large scale and commercially oriented farm holdings in Nigeria. Multistage sampling method was used to randomly select 100 food crop farmers from 10 of the 16 LGAs of Ekiti State. Data was analysed by descriptive statistics, budgetary analysis and the Cobb-Douglas regression technique. The results revealed that the farmers were fairly old with a mean age of 49 years. Their level of education was also very low as 78% did not read beyond primary school level. Average family size was 6 with 96% of the farmers been men. Farm sizes averaged 2.5 hectares while net income was  75,330. Major determinants of farm income were farm size, family size and farm expenditure while determinants of farm size were family size, income and farm expenditure. The study concluded that group farming cooperatives should be encouraged among small holder farmers to enlarge their farms, jointly consume capital inputs and/or assets to reduce costs to increase farm output and farm capitalization. In addition, measures should be put in place to reduce and or eliminate price, institutional and infrastructural challenges that tend to reduce farm income to make farming profitable enough to encourage existing farmers as well as attract new ones.

75,330. Major determinants of farm income were farm size, family size and farm expenditure while determinants of farm size were family size, income and farm expenditure. The study concluded that group farming cooperatives should be encouraged among small holder farmers to enlarge their farms, jointly consume capital inputs and/or assets to reduce costs to increase farm output and farm capitalization. In addition, measures should be put in place to reduce and or eliminate price, institutional and infrastructural challenges that tend to reduce farm income to make farming profitable enough to encourage existing farmers as well as attract new ones.

Keywords:

Commercialization, Agricultural Policy, Food Crops, Input, Diversification, Underutilized, Resources

1. Introduction

The agricultural sector constitute key to achieving a number of critical public policy goals in Nigeria. These goals include: poverty reduction, employment generation, economic diversification and national food security. The national interest in using the sector for these policy objectives is hinged on the enormous agricultural potentials the nation is endowed with. These include: an expansive land area of 923,770 square kilometres (92.4 million hectares) of land, 80% of which is arable[1]. Currently, the agricultural sector employs 60% of the active labour force who operate on small scale. Although the bulk of the food consumed in the nation comes from these small scale farmers, their production systems makes most part of the land resources to be underutilized. These underdeveloped potentials in the sector always provide the necessary attraction for political leaders and policy makers to want to exploit these resources especially when faced with severe socioeconomic problems. Currently, the unemployment rate in the country is 23.9%[2] implying that 39.9 million Nigerians are unemployed while nearly 70% of its population are living below the poverty line. In addition, Nigeria spends as much as  24 trillion (US$160 billion) annually to import food[3]. Given high global food prices and negative developments on oil exports, the ability of the country to sustain its food imports is very doubtful. During periods of socio-economic uncertainties, the agricultural sector becomes the doyen of economic re-construction. Not only does the current government intends to use the sector as the pivot for economic rejuvenation with farmers generating N300 billion (US$ 2billion), it also intends to create 3.5 million jobs in the sector [4] during its four year term ending in year 2015.Incidentally, the agricultural sector presents serious challenges to public policy focus. First, farmers remain one of the poorest economic groups in the country[5]. Second farming is faced with many technical, institutional and economic drawbacks[6] that have seen the fortune of the sector decline continuously over time. It is thus an irony that a sector that has not succeeded in making its operators rich could become the very basis on which the drive for employment generation and poverty reduction can be hinged. While the focus of government is on large scale farmers as key to meeting its food production objectives, the issue is whether to engage a new set of farmers or transform the existing small holder farmers into a commercially oriented one. The reality of the existence of 60% of the Nigerian labour force who are engaged in agriculture and who have borne the responsibility of producing the inadequate food thus far cannot be wished away hence the need to find how best to integrate them in the drive for large scale commercial farming. Critical questions to be answered include: what are the socioeconomic hurdles they have to overcome to profitably participate in the process? what really affect the profitability of existing small holder farms that can become catalytic to transforming the small holder near subsistent farms into medium to large scale commercial entities? and, what are the technological, institutional and price incentives that impact on production?.

24 trillion (US$160 billion) annually to import food[3]. Given high global food prices and negative developments on oil exports, the ability of the country to sustain its food imports is very doubtful. During periods of socio-economic uncertainties, the agricultural sector becomes the doyen of economic re-construction. Not only does the current government intends to use the sector as the pivot for economic rejuvenation with farmers generating N300 billion (US$ 2billion), it also intends to create 3.5 million jobs in the sector [4] during its four year term ending in year 2015.Incidentally, the agricultural sector presents serious challenges to public policy focus. First, farmers remain one of the poorest economic groups in the country[5]. Second farming is faced with many technical, institutional and economic drawbacks[6] that have seen the fortune of the sector decline continuously over time. It is thus an irony that a sector that has not succeeded in making its operators rich could become the very basis on which the drive for employment generation and poverty reduction can be hinged. While the focus of government is on large scale farmers as key to meeting its food production objectives, the issue is whether to engage a new set of farmers or transform the existing small holder farmers into a commercially oriented one. The reality of the existence of 60% of the Nigerian labour force who are engaged in agriculture and who have borne the responsibility of producing the inadequate food thus far cannot be wished away hence the need to find how best to integrate them in the drive for large scale commercial farming. Critical questions to be answered include: what are the socioeconomic hurdles they have to overcome to profitably participate in the process? what really affect the profitability of existing small holder farms that can become catalytic to transforming the small holder near subsistent farms into medium to large scale commercial entities? and, what are the technological, institutional and price incentives that impact on production?.

2. Objectives

The main objective of the study is to examine the prospects of integrating small holder farmers in the new drive for large scale and commercially oriented farm holdings in Nigeria. The specific objectives include to:ⅰ. examine the socio-economic factors affecting food production among small holder farmers in Ekiti State;ⅱ. evaluate the response of farmers to previous policy incentives to enhance food crop production;ⅲ. analyze cost and returns in small holder farms to determine the level of profitability; and,ⅳ. determine the factors critical to the profitability of small holder food crop farmers;

3. The Policy Framework

The policies put in place to drive food output in Nigeria have being very dynamic depending on the developmental goal of the prevailing government. These policies fall into five main phases as discussed below.

3.1. Pre-1970 Period

The policy direction governing the agricultural sector in general and the food crop subsector in particular since independence until recent times were dictated by the philosophical stance of government on the content of agricultural development and the role of government in the development process. From 1960 till about the early 1970s, government pursued a “laissez faire” economic policy that allowed the private sector and particularly the millions of small scale traditional farmers dictate the pace of agricultural development. The role of government was minimal and limited to supporting the activities of the farmers in the area of agricultural research, extension services, export crop marketing, and pricing activities. Where governments created development corporations and farm settlement schemes[7], as was the case in the Western Region, the goals were largely more of welfare than economic considerations. During the period however, the government support placed premium on export crops to the neglect of the food crop subsector.

3.2. Pre-Structural Adjustment Period: 1970 - 1985

The neglect of the food crop subsector in the face of rapid population growth and urbanization soon led to shortages in food crop supply to the local market. Between the early 1970s to mid 1980s, massive oil wealth led to the neglect of the entire agricultural sector which worsened the problem of food shortages as able bodied men and women migrated from the rural areas to the cities. Government response was massive importation of food products to meet domestic demand and imports increased from N756.4 million in 1970 to N12,839.6 in 1981[8]. To solve the fundamental problem of food shortages, government embarked onmulti- dimensional policies, programmes and projects. Spurred on by large incomes from oil exports, government approach shifted from the free market economy of the first decade of independence and embarked on a state-led approach to increase food production between the early 1970s and mid-1980s. Major policy measures affecting the food crop subsector include the establishment of Marketing Board for Food Grains in 1974 with the function of administering guaranteed minimum price policy. It also intervened as a buyer of the last resort in the case of glut in the food market. Major policy instruments included those targeted to inputs supply and distribution, input price subsidy, land resource utilization, agricultural research, extension and farm mechanization, agricultural water resources and irrigation development. While these were laudable efforts, government control was very high which bred inefficiency and considering the shear number of Nigerian food crop farmers and the size of the country, the beneficiaries represented a small enclave that failed to impact substantially on the national food supply situation. In addition, while government promoted food production on one hand, it also embarked on a trade policy regime that made local food products uncompetitive as it imported high quality but cheap food products like rice, wheat flour, maize, vegetable oil and meat products.

3.3 Structural Adjustment Period: 1986 - 1993

By 1985 following international economic crisis that substantially decreased income from oil sources, it became increasingly clear that the state-led approach could not be sustained. Government resorted to adopting the Structural Adjustment Programme, a neo-liberal economic policy that reverted to the post independence view of agriculture primarily as a business that should be led by the private sector and which should form the cornerstone of the emerging economic diversification initiative. Consequently specific and indirect policies which were to last till year 2000 focused on the small scale farmers, who assumed a predominant role in the country’s agricultural recovery and rural development process. The strategy was to increase agricultural production and productivity by improving on the agricultural support systems serving the small scale farmers through improved input supplies; improved extension services; appropriate storage and processing facilities; access to improved technology; and the promotion of off-farm income and employment opportunities mainly through increased private investment in rural agro-processing; provision of credit facilities, infrastructural supplies and other incentives to investors in agriculture. Key instruments included the withdrawal of subsidy on inputs and the partial commercialization of the services provided by key institutions like the River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs)[7]. Trade policies were directed towards liberalization of the import and export markets. To promote local enterprises, items like rice, maize, wheat, barley and vegetable oil were banned while high tariffs were imposed on imported goods that had local substitutes.

3.4. Post-Structural Adjustment Period: 1994 - 2000

The government maintained the policy focus of the SAP period during the post- SAP periods although due to public outcry over increasing poverty caused by the new economic policy, government shifted the policy from SAP to guided deregulation. Subsidy regime for some inputs were re-introduced.

3.5. The New Nigerian Agricultural Policy: 2001 – Date

During this period, a new policy came into effect in 2001 with the new democratic dispensation. The key features of the new policy involves policies that will facilitate the introduction and use of improved inputs, adoption of improved technology, efficient utilization of resources and the encouragement of crop specialization along ecological lines. It also entails minimizing agricultural risks through insurance, a nation-wide unified and all-inclusive extension system under the Agricultural Development Programme (ADP) and the provision of social and physical infrastructures to enhance wellbeing and productivity in the rural areas. The dynamics in policy notwithstanding, food production in Nigeria still fall far short of the national food requirement. While population and urbanization are growing at 3.0% and 5.0% respectively[9], food output is growing at 2.5% and significantly fall short of the annual increase in food demand which has been estimated to be more than 3.5%[10].Subs- tantial resources that could have been used for developmental purposes continued to be channelled into food importation. This has become unacceptable to the government and has opted for a paradigm shift to use the agricultural sector as pivot of its economic transformation agenda to create jobs, make Nigeria a net food exporter, enhancecommercializa- tion and upscale the scale of production in the sector. The thinking among political leaders and policy makers is that farming has for too long been approached from the angle of development and that there is the need to adopt a new paradigm of commercializing agriculture. This thinking follows the internal combustion theory of economic development which posits that an internal growthmechanism supported by technology, specialization, economies of scale in production and sound political and administrative arrangements can be created to promote economic development[11]. This model of development tends to ascribe greater emphasis on the role of government and entrepreneurship in the development process. Given the enormous resources and potentials in the agricultural sector, the thinking is that the failure of entrepreneurial capacity as well as government’s view of agriculture as a developmental rather than an economic project are key factors that have retarded the agricultural sector in Nigeria hence the shift in paradigm and the drive for commercialization and entrepreneurial capacity in the sector. For the agricultural sector to achieve the government goals of economic reconstruction and employment generation, certain conditions must be met. According to[12], anagricul-ture and employment based strategy of achieving economic development requires three basic but complementary elements:ⅰ. accelerated output growth through technological, institutional and price incentive changes designed to raise the productivity of small farmers;ⅱ. rising domestic demand for agricultural output derived from employment-oriented urban development strategy; and.ⅲ. diversified non-agricultural labour-intensive rural development activities that directly support and are supported by the farming communities. Although the second condition is largely met in Nigeria, the first and third are far from being actualized. These are the critical factors that policy issues in agriculture should address.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling Technique and Data Collection

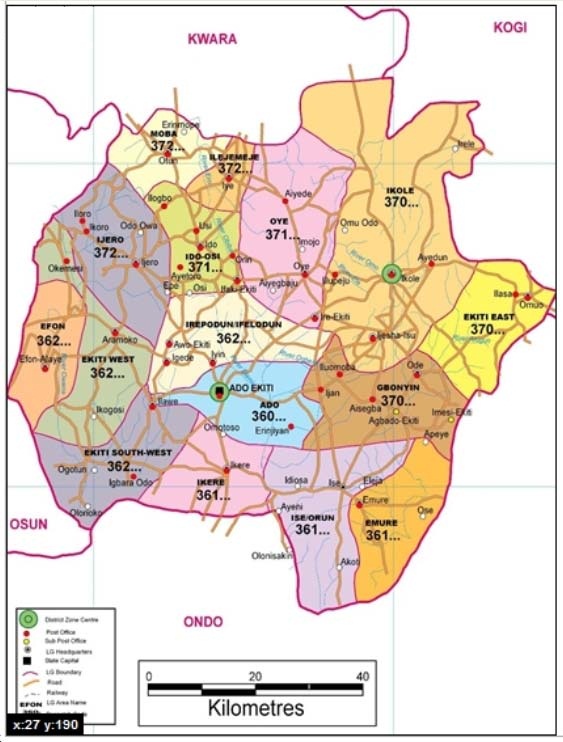

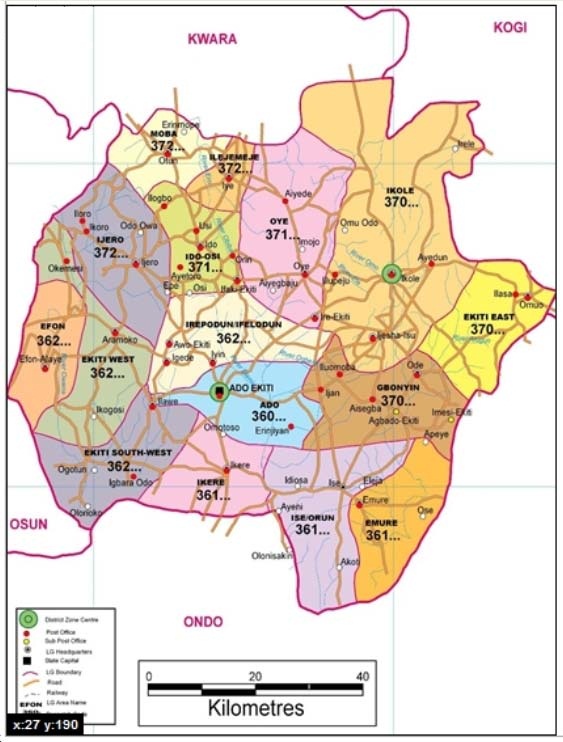

The study was carried out in Ekiti State. The State (figure 1) which is situated in the southwest geopolitical zone is located between longitudes 40 51E and 50 451E and latitudes 70 151N and 80 51 N. The State lies south of Kwara and Kogi States, East of Osun State and bounded by Ondo State in the East and in the south[13]. Ekiti State has 16 Local Government Councils and a population of 2,384,212[9].The multistage sampling technique was used to select 100 farmers from 10 of the 16 local government areas of the State. First, the State was purposively selected because it is the most rural of the States in the southwest zone with ample food crop farmers. Secondly, 10 LGAs were randomly selected out of the 16 LGAs while at the third stage, 10 farmers were randomly selected from 10 rural farming communities in the State. Data were collected from respondents with the aid of pre-tested structured questionnaire.

4.2. Data Analysis

| Figure 1. Map of Ekiti State, South West, Nigeria |

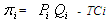

Data collected were analysed using descriptive statistics, budgetary analysis and the Cobb-Douglas regression model. Descriptive statistics, including frequency counts, means and percentages were used to describe the socio-economic characteristics (age, family size, farm size) of selected food crop producers in the study area. Budgetary analysis was employed to estimate costs and returns to food crop production using the gross margin as stated in equation (1):  | (1) |

where, = gross margin per hectare (

= gross margin per hectare ( /ha),

/ha), = price per unit of food crops produced (

= price per unit of food crops produced ( ),

), = food crop output ( Kg), and,TCi = total costs of production (fixed cost {FC} plus variable cost {VC}) (

= food crop output ( Kg), and,TCi = total costs of production (fixed cost {FC} plus variable cost {VC}) ( )Variable costs (VC) included in the analysis were expenditures on labour, seedlings, fertilizers, agrochemicals and transportation. Items that could be used for more than a production cycle were classified as fixed costs (FC). These included cutlasses, sprayers and farm-bans. Finally, two multiple regression models were used to estimate the socio-economic factors determining farm income as well as those determining farm size among arable crop producers in the study area. The model on factors determining farm income was specified as:

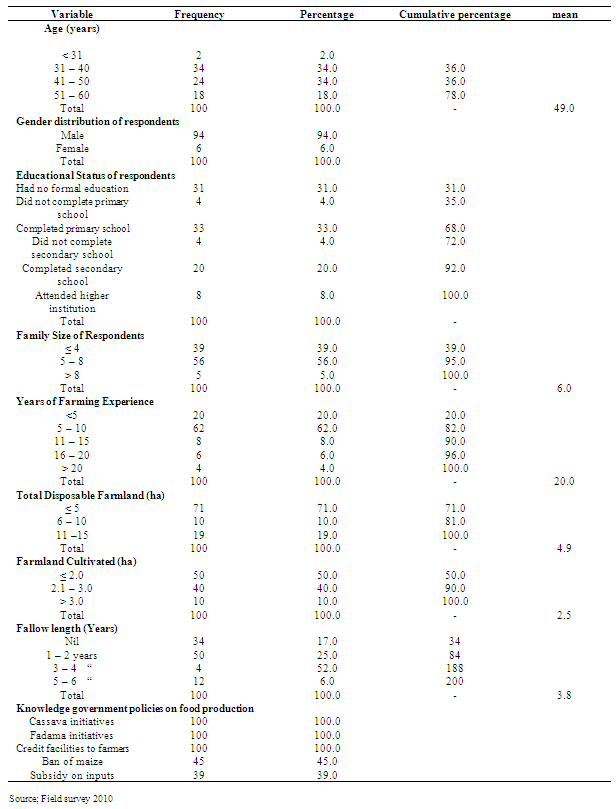

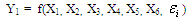

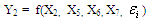

)Variable costs (VC) included in the analysis were expenditures on labour, seedlings, fertilizers, agrochemicals and transportation. Items that could be used for more than a production cycle were classified as fixed costs (FC). These included cutlasses, sprayers and farm-bans. Finally, two multiple regression models were used to estimate the socio-economic factors determining farm income as well as those determining farm size among arable crop producers in the study area. The model on factors determining farm income was specified as: | (2) |

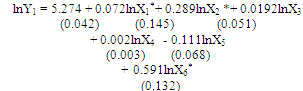

where,Y1 = income from food crops ( )X1 = farm size (ha)X2= family size X3= fallow length (years)X4= educational level of respondents (years spent in formal schools)X5= age of respondents (years) X6= farm expenditure (

)X1 = farm size (ha)X2= family size X3= fallow length (years)X4= educational level of respondents (years spent in formal schools)X5= age of respondents (years) X6= farm expenditure ( )

) = error term.In terms of a priori expectations, X1, X3, X4, and X6 are expected to be positively correlated to farm income while X2, could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit. X5 is expected to be positively correlated to farm income to a certain age where it starts to show a negative relationship as increasing age affects the productivity of farmers.The model on factors affecting farm size in small holder farm enterprises was also specified as:

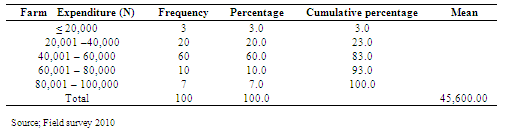

= error term.In terms of a priori expectations, X1, X3, X4, and X6 are expected to be positively correlated to farm income while X2, could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit. X5 is expected to be positively correlated to farm income to a certain age where it starts to show a negative relationship as increasing age affects the productivity of farmers.The model on factors affecting farm size in small holder farm enterprises was also specified as:  | (3) |

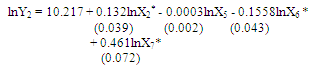

where,Y2 = farm size (ha)X7 = farm income ( ) X2, X5, X6, and

) X2, X5, X6, and  are as defined earlier.A priori expectations was for X5, X6, and X7 to be positively correlated to total farm size while X2 could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit.

are as defined earlier.A priori expectations was for X5, X6, and X7 to be positively correlated to total farm size while X2 could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit.

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Small Holder Farmers

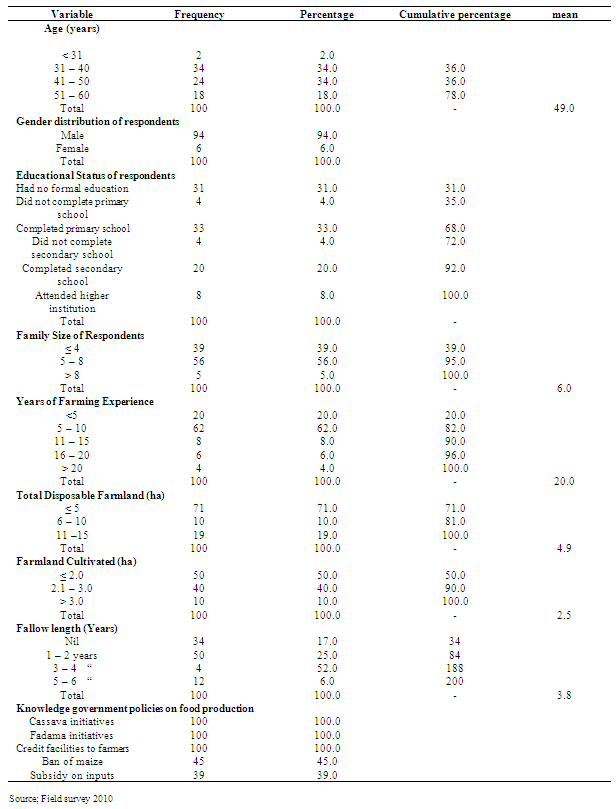

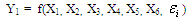

As shown in Table 1, the mean age of the sampled farmers was 49 years with as much as 22% of them ageing above sixty years. Clearly, most of the farmers were fairly old and are schooled in the traditional method of farming using hoes and cutlasses as the mean farming experience for these farmers as shown in Table 1 was 20 years. It could be difficult for these set of farmers to take risks that will involve contracting loans for farm capitalization that is imperative in the transformation of small holder enterprises to large scale commercial entities. The level of education among the farmers was very low with as much as 72% not educated beyond elementary primary school. Only 28% had secondary school education. The very low educational level will affect the capacity of the farmers to access and use information, innovations and ideas that could enhance farm capitalization. In fact they might find it difficult to appreciate the new policy drive of government aimed at transforming the agricultural sector and how to access and utilize opportunities to achieve this goal. To successfully transform agriculture to large scale commercial entities, while not neglecting the present crop of farmers, efforts should be made to attract young, educated and energetic farmers into the agricultural sector. Fortunately, the policy document places more emphasis on “new farmers”.Majority of the farmers (94%) were male indicating that in the study area, food crop farming is a male dominated enterprise hence, for the transformation of the food crop sub-sector into commercial farms, attention should be focused on the male gender. In the study area, most of the women are traders and food processors hence, commercialization of the farm production sector should encompass a whole value chain process such that the women in the farm household can effectively participate either as processors and/or marketers of the farm products. Transformation of the agricultural sector will not come cheap as it will require massive investment in farm capitalization. Since men are the dominant farmers the whole wellbeing of the rural households and their capacity to save for future investment will depend solely on the incomes earned by the men. Also, since agricultural income among small holder farmers are generally low ([14],[15]) the funds for farm investment and capitalization will have to come from outside agriculture in which case public and or financial institutions able to give medium to long term credit to the food crop subsector will be critical.Compared to studies in other areas in the nation ([16],[17]), family sizes were fairly small with a mean family size of 6. While this could positively enhance the well being of the farmers as well as savings, it could also adversely affect farm operations as family labour, the most dependable resource in smallholder agriculture will be severely limited. However, transformation of the agricultural sector will entail introduction of farm mechanization which will not require too much labour. The small family sizes also mean drastic reduction in the agricultural population who depend solely on the land to survive thereby freeing land for the fewer farmers to cultivate larger farm holdings.Land is critical to farm transformation as its availability and access affects the size of farm lands and the capacity of farmers to transit into medium to large scale farms. In the study area, the mean disposable farm land per farmer was 4.0 hectares. In fact as much as 71% of the respondents had less than 5 hectares for farming and for fallow. A major challenge that the transformation agenda will face in the study area as well as the southern region of Nigeria is how to access farmers to large tracts of land that will enable large scale commercial farming. There are no empty lands and even currently, the small farmers do not have enough land for their farming activities. Although the Land Use Act vests ownership of land in the government[18], the reality on ground in the study area is that land belongs to the family and those who own the land do not take permission from the government. Farm sizes in the study area were also small averaging 2.5 hectares and slightly above the national average of 2.0 ha[19]. Farm sizes are this small given the small sizes of farm households and the fact that Ekiti State is in the fore front of acquiring western education among the States in the country, hence the school age children are most likely to be in school and as such not available to provide support in the farms.Table 1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Respondents

|

| |

|

5.2. Awareness and Response of Farmers to Existing Policies on Food Production

Field survey revealed that all the respondents claimed they were aware of some of the government policies directed at enhancing food crop production. The Farmers were all aware of the cassava initiative of government, the Fadama initiative and credit facilities through commercial and specialized banks. Forty five percent were aware that maize importation has been banned while another 39% mentioned the existence of subsidy on farm inputs (Table 1). While 75% of the farmers got to know through radio jingles and programmes, 25% came to know through relatives and friends. Curiously, all the farmers claimed they have not benefitted from any of the policies. Clearly, government programmes and policies have not made much impact on the farmers. This fact is reflected in the size of the farms cultivated, very little use of inputs and low farm capitalization. Except government policies are properly implemented and targeted at the right groups of farmers, the effect of policies will continue to be minimal and the nation’s goal of achieving self sufficiency in food production will be a mirage.

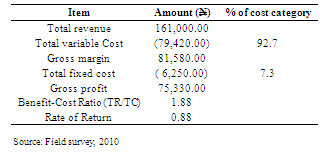

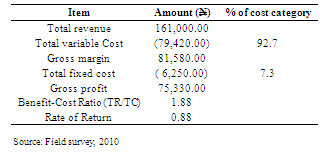

5.3. Cost and Returns to Farming Enterprise

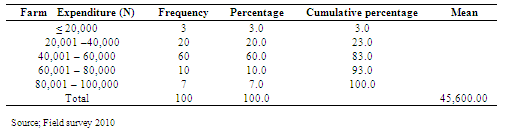

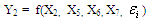

Commercialization involves producing to maximize profit. It also implies producing large quantities of farm produce to take advantage of the large markets as well as reduce marginal cost. To achieve this, especially since the land available for farming and fallow was relatively small, improved farm inputs that will enhance output, reduce the drudgery of farm work as well increase farm size become essential. In the study area, only three farm inputs namely labour, fertilizer and herbicide were purchased by the farmers. In fact labour constituted over 90% of total farm expenditure. On the aggregate as shown in Table 2, the mean expenditure on farm production on these three inputs was N  45,600. As much as 83% of the farmers did not spend more than

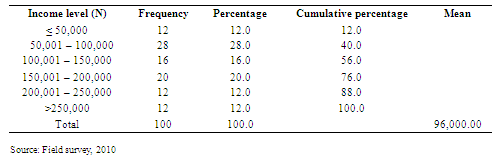

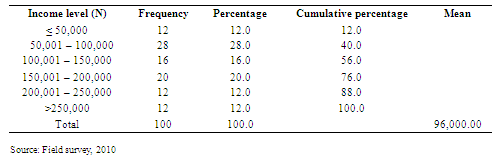

45,600. As much as 83% of the farmers did not spend more than  60,000 on their farm during the farm year. Clearly, farm commercialization, capitalization as well as transformation cannot be achieved without investment on farm holdings. While these set of farmers should be encouraged to invest in their enterprises through aggressive extension systems, new farmers who appreciate the importance of farm investment towards making profit should be encouraged to take farming as a vocation.Table 3 shows the distribution of income among farmers. The mean income realized by farmers was N96,000. For 81% of the farmers who had no other secondary occupation, this amount is very small for the farmers to save anything after meeting household expenses. It probably is the reason farmers hold tenaciously to traditional farming systems so they can survive with low resource inputs into their farming business. Transforming the farming system of food crop farmers will require identifying opportunities that can make farmers produce more as well as earn higher incomes.The main crops cultivated by farmers were cassava, yam and maize. Table 4 shows that the gross margin to enterprise was

60,000 on their farm during the farm year. Clearly, farm commercialization, capitalization as well as transformation cannot be achieved without investment on farm holdings. While these set of farmers should be encouraged to invest in their enterprises through aggressive extension systems, new farmers who appreciate the importance of farm investment towards making profit should be encouraged to take farming as a vocation.Table 3 shows the distribution of income among farmers. The mean income realized by farmers was N96,000. For 81% of the farmers who had no other secondary occupation, this amount is very small for the farmers to save anything after meeting household expenses. It probably is the reason farmers hold tenaciously to traditional farming systems so they can survive with low resource inputs into their farming business. Transforming the farming system of food crop farmers will require identifying opportunities that can make farmers produce more as well as earn higher incomes.The main crops cultivated by farmers were cassava, yam and maize. Table 4 shows that the gross margin to enterprise was  81,590.00 while the gross profit was

81,590.00 while the gross profit was  75,330.00. The Benefit-Cost Ratio of 1.88 indicates that small holder farm businesses are profitable in the study area as every

75,330.00. The Benefit-Cost Ratio of 1.88 indicates that small holder farm businesses are profitable in the study area as every  100 invested in the enterprise yields additional

100 invested in the enterprise yields additional  88 over and above the initial amount invested. However, variable cost constituted 92.7% which indicates that small holder farming is very flexible. The proportion of fixed capital of 7.3% shows that the level of farm capitalization in small holder farms is very low. The rate of return of 88% indicates that small holder farm holdings are profitable as it returns more than interest rates in conventional banks. This implies that if these farmers can be accessed to loans, they will be able to pay them back.

88 over and above the initial amount invested. However, variable cost constituted 92.7% which indicates that small holder farming is very flexible. The proportion of fixed capital of 7.3% shows that the level of farm capitalization in small holder farms is very low. The rate of return of 88% indicates that small holder farm holdings are profitable as it returns more than interest rates in conventional banks. This implies that if these farmers can be accessed to loans, they will be able to pay them back. Table 2. Farm expenditure incurred by respondents

|

| |

|

Table 3. Income distribution among respondents

|

| |

|

Table 4. Analysis of Costs and Returns in Small holder Farms

|

| |

|

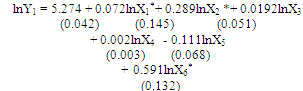

5.4. Factors Affecting Incomes in Smallholder Agriculture

| (4) |

R2 = 0.782 Adjusted R2 = 0.760 F-ratio = 16.756*(figures in parentheses are the standard errors)* significant at 5% level.Equation (4) shows that with the exception of age of respondents (X5) which was negatively correlated with income, all other variables: farm size (X1), family size (X2), fallow length (X3), level of education (X4) and farm expenditure (X6) were positively correlated with farm income. However, only three of these variables: farm size (X1), family size (X2) and farm expenditure (X6) were statistically significant.As shown in equation (4), farm size (X1) is positively correlated with income in small holder farm enterprises and is in conformity with a priori expectations. The variable was statistically significant. The coefficient of the variable indicates that a unit increase in farm size will lead to a corresponding 7.2% increase in farm income. Clearly, even in small holder agriculture, there is the need to increase farm size to realize higher incomes and doing this is in perfect agreement with the transformation agenda. Family size (X2) was also positively correlated with farm income and also in agreement with a priori expectations as well as statistically significant. A unit increase in family size will lead to a corresponding 28.9% increase in farm income. In agreement with a priori expectations, farm expenditure (X6) was also positively correlated with farm income and is statistically significant. The coefficient of the variable indicates that a unit increase in farm expenditure will lead to an increase in farm income by 59.1%. Although not statistically significant, the age of farmers (X5) was negatively correlated with farm income. As farmers’ age, their ability to carry out the laborious farm tasks associated with traditional agriculture diminishes which reduces farm size, management of crops and hence, income. Fallow lengths (X3) and educational level of farmers (X4) were also not statistically significant but were in conformity with a priori expectations as they were positively correlated with farm income. The adjusted coefficient of determination of 0.76 indicates that 76% of the variability in income from food crop farms of small holder enterprises is associated with the variables specified in the model.

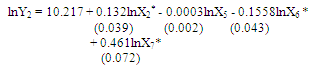

5.5. Factors Affecting Farm Sizes in Smallholder Agriculture

| (5) |

R2 = 0.671 Adjusted R2 = 0.652 F-ratio = 25.134*(figures in parentheses are the standard errors)* significant at 5% level.As shown in equation (5) family size (X2) and farm income (X7) were positively correlated with farm size in conformity with a priori expectations. The two variables were also statistically significant. Farm expenditure (X6) was negatively correlated with farm size and not in conformity with a priori expectations although statistically significant while age (X5) was negatively correlated with farm size in conformity with a priori expectations. It was however not statistically significant. Equation (5) indicates that a unit increase in family size (X2) will increase farm size by 13.2%. This is quite understandable since an increase in family size will provide extra labour to work on the farm. It also shows that the family unit in the study area is productive and that all members of the household are engaged in the farm business. The model also shows that a unit increase in farm income (X7) will lead to a corresponding increase in farm size by 46.1%. This clearly shows that the small holder farm enterprises seeks to maximize returns to efforts hence, extra income is a very strong incentive to increasing farm sizes. Equation (5) further shows that a unit increase in farm expenditure (X6) will depress farm size by16 %. The main expenditure item in small farm holdings is labour although some also invested in fertilizer and herbicides. The result shows clearly that given the existing farm size, extra expenditure in the farm will be a disincentive to increase farm size. There is thus the need to improve on measures that will reduce farm expenditure. First, since labour constitute over 90% of the cost item in the farmers farm expenses, labour saving devices that will be cost effective should be made available to farmers to reduce farm expenses. Secondly, farm inputs should be channelled through farmers’ cooperatives to reach the farmers. Food is a security issue hence, leaving factors that affect food production entirely in the hand of the market with its tendency to exploit the economically weak is not healthy for the food security objective of the nation. That is why policy efforts should be made to strengthen agricultural cooperative organizations and distribute inputs through them to farmers. Age of farmer (X5) though not statistically significant, was negatively correlated indicating that as farmers grow older, they become weak and without the requisite resources to engage hired labour are not able to operate large farms. The adjusted coefficient of determination of 0.652 indicates that about 65% of the variability in farm size in small holder agriculture is associated with the variables specified in the model.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Food crop farmers in Ekiti State were old, had little education and operated small sized farms. In addition, very little capital and farm improving inputs were used in the farm business hence, incomes were very low. Farmers were aware of some policy measures put in place to encourage farmers to increase farm production but none of them accessed these opportunities. Clearly, the socio-economic realities of the smallholder food crop farmers are not attractive to the new commercialization drive. Efforts should be made to attract new, educated, young and energetic farmers who are schooled in the business of agriculture. Such farmers could be attracted from university and college graduates if the necessary incentives in terms of credit, fertile agricultural lands and infrastructural supply are provided. The response of small holder farmers to profit as established in the study indicates that the door to commercialization of agriculture cannot be closed against the small holder farmers. This is more so where there has been a gap between policy formulation and implementation agencies as well as the farmers who were supposed to benefit from these policies. To overcome the socio-economic shortcomings of the small scale food crop farmers, efforts should be made to group participants in the farm transformation process into cooperative groups to engage in group farming where each farmer owns his own farm plot but jointly shares facilities for farm mechanization and improvement. Farm sizes can be increased to achieve economies of scale in medium to large scale farms while training on policy objectives, improved farming practices, processing and marketing of farm produce can be accessed these farmers by extension agents.Secondly, since increased earnings is a strong incentive in increasing small holder farm sizes, policy measures should be put in place to remove the price, institutional and infrastructural distortions that tend to depress food crop prices and hence incomes to farmers. For example linkage of rural farmers to urban markets through provision of quality roads and market information will reduce the activities of middlemen who tend to buy at low prices at the farm gate. Measures that purchases surplus outputs during harvest times when there tend to be glut will further help to stabilize prices in favour of the farmer while the provision of electricity and other infrastructures will encourage the development of non-farm processing enterprises that will enhance the value chain in the agricultural business, attract excess farmers away from the land and provide catalytic impetus for the development of the rural economy.

References

| [1] | Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA) Transition to Sustainable Development in Nigeria Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.1992. |

| [2] | Business Day, Lagos Nigeriahttp://www.businessdayonline.com Friday March 30, 2012 |

| [3] | The Guardian, Lagos, Nigeriahttp://www.ngrguardiannews.com Sunday Ocober 16, 2011. |

| [4] | National Mirror, Lagos Nigeriahttp://www.nationalmirroronline.net Friday March 30, 2012. |

| [5] | Aigbokhan, E.B. “Determinants of Regional Poverty in Nigeria”. Research Report No. 22, Development Policy Centre, Ibadan, Nigeria, 33 Pages. 2000. |

| [6] | Oluwasola, O. and S.R.A. Adewusi “Food Security in Nigeria: The Way Forward” in Adebooye, C.O., Taiwo, K.A. and Fatufe, A.A (eds.) Food, Health and Environmental Issues in Developing Countries: The Nigerian Situation. Cuvillier Verlag, Gottingen, Germany. Pp 448 – 470, 2008. |

| [7] | Manyong, V.M., Ikpi, A., Olayemi, J.K., Yusuf, S.A., Omonona, B.T., Okoruwa, V. and F.S Idachaba “Agriculture in Nigeria: Identifying Opportunities for Increased Commercialization and Investment”. IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria. 2005. |

| [8] | Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Statistical Bulletin. 2005. |

| [9] | National Population Commission “Nigeria’s National Census”, NPC, Abuja, Nigeria. 2006 |

| [10] | Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) “Fact Book” August 16, 2007. |

| [11] | Akinyosoye V.O. Government and Agriculture in Nigeria: Analysis of Policies Programmes and Administration. Macmillan, Nigeria Publishers Limited, Lagos, Nigeria. 2005. |

| [12] | Todaro, M.P. and Smith, S.C Economic development (8th edition). Pearson Education Publishers, Delhi, India. 2006. |

| [13] | Ekiti State Government Official Website of Ekiti State Government. 2011.http://ekitistate.gov.ng/about-ekiti/overview/ |

| [14] | Oluwasola O. and T. Alimi “Determinants of agricultural credit demand and supply among small-scale farmers in Nigeria” Outlook on Agriculture Vol. 37 No. 3 Pp185 – 193. 2008. |

| [15] | Zeller, M., Schrieder, G., Von Braun, J., and Heidhues, F. Rural Finance for Food Security for the Poor: Implications for Research and Policy. Food Policy Review 4, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, D.C. USA. 1997. |

| [16] | Idowu E.O. and R. Kassali “Determinants of farm income in the peri-urban agriculture of Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria” in R. Adeyemo (ed.) Urban Agriculture, Cities and Climate Change. Cuvillier Verlag Cottingen, Germany. Pp 75 – 80. 2011. |

| [17] | Aihonsu, J.O.Y “Comparative Economic Analysis of Upland and Swamp Rice Production systems in Ogun State Nigeria”. Ph. D Agricultural Economics thesis Department of Agricultural Economics, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. 206pages. 2002 |

| [18] | Udo R.K. The National Land Policy of Nigeria. Research Report No. 16. Development Policy Centre (DPC), Ibadan, Nigeria. pp1 – 100. 1999. |

| [19] | Nigerian National Committee on Irrigation and Drainage (NINCID) Annual Report, Abuja, Nigeria. 2006. |

75,330. Major determinants of farm income were farm size, family size and farm expenditure while determinants of farm size were family size, income and farm expenditure. The study concluded that group farming cooperatives should be encouraged among small holder farmers to enlarge their farms, jointly consume capital inputs and/or assets to reduce costs to increase farm output and farm capitalization. In addition, measures should be put in place to reduce and or eliminate price, institutional and infrastructural challenges that tend to reduce farm income to make farming profitable enough to encourage existing farmers as well as attract new ones.

75,330. Major determinants of farm income were farm size, family size and farm expenditure while determinants of farm size were family size, income and farm expenditure. The study concluded that group farming cooperatives should be encouraged among small holder farmers to enlarge their farms, jointly consume capital inputs and/or assets to reduce costs to increase farm output and farm capitalization. In addition, measures should be put in place to reduce and or eliminate price, institutional and infrastructural challenges that tend to reduce farm income to make farming profitable enough to encourage existing farmers as well as attract new ones.

24 trillion (US$160 billion) annually to import food[3]. Given high global food prices and negative developments on oil exports, the ability of the country to sustain its food imports is very doubtful. During periods of socio-economic uncertainties, the agricultural sector becomes the doyen of economic re-construction. Not only does the current government intends to use the sector as the pivot for economic rejuvenation with farmers generating N300 billion (US$ 2billion), it also intends to create 3.5 million jobs in the sector [4] during its four year term ending in year 2015.Incidentally, the agricultural sector presents serious challenges to public policy focus. First, farmers remain one of the poorest economic groups in the country[5]. Second farming is faced with many technical, institutional and economic drawbacks[6] that have seen the fortune of the sector decline continuously over time. It is thus an irony that a sector that has not succeeded in making its operators rich could become the very basis on which the drive for employment generation and poverty reduction can be hinged. While the focus of government is on large scale farmers as key to meeting its food production objectives, the issue is whether to engage a new set of farmers or transform the existing small holder farmers into a commercially oriented one. The reality of the existence of 60% of the Nigerian labour force who are engaged in agriculture and who have borne the responsibility of producing the inadequate food thus far cannot be wished away hence the need to find how best to integrate them in the drive for large scale commercial farming. Critical questions to be answered include: what are the socioeconomic hurdles they have to overcome to profitably participate in the process? what really affect the profitability of existing small holder farms that can become catalytic to transforming the small holder near subsistent farms into medium to large scale commercial entities? and, what are the technological, institutional and price incentives that impact on production?.

24 trillion (US$160 billion) annually to import food[3]. Given high global food prices and negative developments on oil exports, the ability of the country to sustain its food imports is very doubtful. During periods of socio-economic uncertainties, the agricultural sector becomes the doyen of economic re-construction. Not only does the current government intends to use the sector as the pivot for economic rejuvenation with farmers generating N300 billion (US$ 2billion), it also intends to create 3.5 million jobs in the sector [4] during its four year term ending in year 2015.Incidentally, the agricultural sector presents serious challenges to public policy focus. First, farmers remain one of the poorest economic groups in the country[5]. Second farming is faced with many technical, institutional and economic drawbacks[6] that have seen the fortune of the sector decline continuously over time. It is thus an irony that a sector that has not succeeded in making its operators rich could become the very basis on which the drive for employment generation and poverty reduction can be hinged. While the focus of government is on large scale farmers as key to meeting its food production objectives, the issue is whether to engage a new set of farmers or transform the existing small holder farmers into a commercially oriented one. The reality of the existence of 60% of the Nigerian labour force who are engaged in agriculture and who have borne the responsibility of producing the inadequate food thus far cannot be wished away hence the need to find how best to integrate them in the drive for large scale commercial farming. Critical questions to be answered include: what are the socioeconomic hurdles they have to overcome to profitably participate in the process? what really affect the profitability of existing small holder farms that can become catalytic to transforming the small holder near subsistent farms into medium to large scale commercial entities? and, what are the technological, institutional and price incentives that impact on production?.

= gross margin per hectare (

= gross margin per hectare ( /ha),

/ha), = price per unit of food crops produced (

= price per unit of food crops produced ( ),

), = food crop output ( Kg), and,TCi = total costs of production (fixed cost {FC} plus variable cost {VC}) (

= food crop output ( Kg), and,TCi = total costs of production (fixed cost {FC} plus variable cost {VC}) ( )Variable costs (VC) included in the analysis were expenditures on labour, seedlings, fertilizers, agrochemicals and transportation. Items that could be used for more than a production cycle were classified as fixed costs (FC). These included cutlasses, sprayers and farm-bans. Finally, two multiple regression models were used to estimate the socio-economic factors determining farm income as well as those determining farm size among arable crop producers in the study area. The model on factors determining farm income was specified as:

)Variable costs (VC) included in the analysis were expenditures on labour, seedlings, fertilizers, agrochemicals and transportation. Items that could be used for more than a production cycle were classified as fixed costs (FC). These included cutlasses, sprayers and farm-bans. Finally, two multiple regression models were used to estimate the socio-economic factors determining farm income as well as those determining farm size among arable crop producers in the study area. The model on factors determining farm income was specified as:

)X1 = farm size (ha)X2= family size X3= fallow length (years)X4= educational level of respondents (years spent in formal schools)X5= age of respondents (years) X6= farm expenditure (

)X1 = farm size (ha)X2= family size X3= fallow length (years)X4= educational level of respondents (years spent in formal schools)X5= age of respondents (years) X6= farm expenditure ( )

) = error term.In terms of a priori expectations, X1, X3, X4, and X6 are expected to be positively correlated to farm income while X2, could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit. X5 is expected to be positively correlated to farm income to a certain age where it starts to show a negative relationship as increasing age affects the productivity of farmers.The model on factors affecting farm size in small holder farm enterprises was also specified as:

= error term.In terms of a priori expectations, X1, X3, X4, and X6 are expected to be positively correlated to farm income while X2, could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit. X5 is expected to be positively correlated to farm income to a certain age where it starts to show a negative relationship as increasing age affects the productivity of farmers.The model on factors affecting farm size in small holder farm enterprises was also specified as:

) X2, X5, X6, and

) X2, X5, X6, and  are as defined earlier.A priori expectations was for X5, X6, and X7 to be positively correlated to total farm size while X2 could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit.

are as defined earlier.A priori expectations was for X5, X6, and X7 to be positively correlated to total farm size while X2 could be either positively or negatively correlated depending on whether it is a production or consumption unit.  45,600. As much as 83% of the farmers did not spend more than

45,600. As much as 83% of the farmers did not spend more than  60,000 on their farm during the farm year. Clearly, farm commercialization, capitalization as well as transformation cannot be achieved without investment on farm holdings. While these set of farmers should be encouraged to invest in their enterprises through aggressive extension systems, new farmers who appreciate the importance of farm investment towards making profit should be encouraged to take farming as a vocation.Table 3 shows the distribution of income among farmers. The mean income realized by farmers was N96,000. For 81% of the farmers who had no other secondary occupation, this amount is very small for the farmers to save anything after meeting household expenses. It probably is the reason farmers hold tenaciously to traditional farming systems so they can survive with low resource inputs into their farming business. Transforming the farming system of food crop farmers will require identifying opportunities that can make farmers produce more as well as earn higher incomes.The main crops cultivated by farmers were cassava, yam and maize. Table 4 shows that the gross margin to enterprise was

60,000 on their farm during the farm year. Clearly, farm commercialization, capitalization as well as transformation cannot be achieved without investment on farm holdings. While these set of farmers should be encouraged to invest in their enterprises through aggressive extension systems, new farmers who appreciate the importance of farm investment towards making profit should be encouraged to take farming as a vocation.Table 3 shows the distribution of income among farmers. The mean income realized by farmers was N96,000. For 81% of the farmers who had no other secondary occupation, this amount is very small for the farmers to save anything after meeting household expenses. It probably is the reason farmers hold tenaciously to traditional farming systems so they can survive with low resource inputs into their farming business. Transforming the farming system of food crop farmers will require identifying opportunities that can make farmers produce more as well as earn higher incomes.The main crops cultivated by farmers were cassava, yam and maize. Table 4 shows that the gross margin to enterprise was  81,590.00 while the gross profit was

81,590.00 while the gross profit was  75,330.00. The Benefit-Cost Ratio of 1.88 indicates that small holder farm businesses are profitable in the study area as every

75,330.00. The Benefit-Cost Ratio of 1.88 indicates that small holder farm businesses are profitable in the study area as every  100 invested in the enterprise yields additional

100 invested in the enterprise yields additional  88 over and above the initial amount invested. However, variable cost constituted 92.7% which indicates that small holder farming is very flexible. The proportion of fixed capital of 7.3% shows that the level of farm capitalization in small holder farms is very low. The rate of return of 88% indicates that small holder farm holdings are profitable as it returns more than interest rates in conventional banks. This implies that if these farmers can be accessed to loans, they will be able to pay them back.

88 over and above the initial amount invested. However, variable cost constituted 92.7% which indicates that small holder farming is very flexible. The proportion of fixed capital of 7.3% shows that the level of farm capitalization in small holder farms is very low. The rate of return of 88% indicates that small holder farm holdings are profitable as it returns more than interest rates in conventional banks. This implies that if these farmers can be accessed to loans, they will be able to pay them back.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML