Tata Precillia Ijang1, Ndikumagenge Cleto2, Ngome Williams Ewane3, Agostinho Chicaia4, Ron Tamar5

1Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (Cameroon), Main consultant Mayombe project, P.O. Box 2067, IRAD Nkolbisson, Yaounde, Cameroon

2Facilitator Delegate for the Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP)

3Intern, Institute of Agricultural Research for Development ,Cameroon

4Mayombe transfrontier project Regional Coordinator, Pointe Noire Congo

5Principal Consultant, Mayombe transfrontier project ,Angola

Correspondence to: Tata Precillia Ijang, Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (Cameroon), Main consultant Mayombe project, P.O. Box 2067, IRAD Nkolbisson, Yaounde, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

This paper questions the conduct of key processes and outcome of preliminary actions leading to national engagements and commitment for the management of transboundary protected areas and how these fit into the broader picture of multi-stakeholder negotiation and collaboration framework. Using the participatory learning and action method, authors accompanied stakeholders (consultants, facilitators, experts and Ministers from Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Congo) in negotiating the Mayombe forest transboundary protected area. Main activities carried out were baseline studies, internal meetings and multiparty meetings organized in the respective countries, Kinshasa (DRC) and Cabinda (Angola). Results show that the negotiation process was initially win-lose during the first multiparty meeting. These worsen to a lose-lose scenario in the second meeting. At this stage the process was rather externally-driven. After serious internal meetings and the intervention of senior officials it finally moved to a win-win situation as a result of increased national ownership. Since the ministers from the three countries were able to reverse the negotiation outcome, it appears that the views of high level government authorities are essential in preliminary arrangements in transboundary dialogue and cooperation. As such, protected areas negotiation schemes should not be limited to technical expertise but rather be inclusive of politics at the national and regional level. It is expected that increased national-level and local-level ownership would further improve the win-win tendencies

Keywords:

Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Congo, Mayombe forest transboundry protected area, negotiation, participatory learning, stakeholders

Cite this paper: Tata Precillia Ijang, Ndikumagenge Cleto, Ngome Williams Ewane, Agostinho Chicaia, Ron Tamar, Transboundary Dialogue and Cooperation: First Lessons from Igniting Negotiations on Joint Management of the Mayombe Forest in the Congo Basin, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 2 No. 3, 2012, pp. 121-131. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20120203.08.

1. Introduction

Natural resource management problems are generally interdependent and transcend boundaries[1] complicating their management. This is even worst for transboundary forest resources in states in states with weak governance and law enforcement, which often constitute violent and lawless border areas[2]. Such forest landscapes (like the Mayombe forest1) are generally characterised by high migration and poverty rates, presence of armed groups, circulation of small arms, difficult accessibility due to poor infrastructural development and high uncontrolled transboundary economic and social exchanges ([3-8]). Improved resource management does not only depend on the cooperation of field stakeholders but also on interstate engagements and regional polities (form and process of government that could influence decisions and outcomes that may affect the landscape at the local, national and regional levels). Transboundary dialogue and cooperation is not new in Africa. Many countries have various landscapes of common interest like the Sangha Trinational Park (between Cameroon, Congo and Central Africa Republic (CAR)), the Virunga landscape (between Rwanda, Uganda and DRC), the TRIDOM landscape (between Cameroon, Gabon and CAR) etc ([4,9]). Most articles on multi-stakeholder negotiation and collaboration processes often focus on technical issues and actual interaction between implementing partners in the long run ([1,9,10]). Such analyses fail to capture high level policy negotiations and level of influence. As well, they do not document the initial forms of and approaches used in reaching agreements between countries (parties). By not taking into account such preliminary efforts, these analyses do not provide a complete picture and substantial learning lessons on the ground rules guiding the negotiation and collaboration processes. This can obscure real implementation, future evaluation processes and the resolution of conflicts that might arise. Our research and subsequent analysis attempts to link and build a foundation for transboundary dialogue and cooperation by seeking answers to the following questions: 1.What are the key processes and outcomes of the preliminary efforts in these negotiations? 2. How do the preliminary efforts fit into the broader picture of multi- stakeholder negotiation and collaboration framework? 3. What are the subgroups? 4. What is the role of each subgroup? 5. What is the level of influence of each subgroup?With these questions in mind, this paper depicts how preliminary arrangements that set the ground rules for further collaboration on the Mayombe landscape transpired. These include action that resulted to the signing of agreements and other engagement acts between Congo, DRC and Angola. It links practice on first lessons from igniting negotiations on joint management of the forest ecosystem to theories on multi-actor negotiation and collaboration. Results will produce evidence on the way national engagements and polities combined to produce outcome to guide natural resource management processes.

2. Description of the Mayombe Forest Landscape and the Mayombe Transfrontier Project

The Mayombe forest is shared between the Republic of Gabon, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. It contains 6 Protected Areas: Myumba National Park (Gabon), Conkouati-Douli National Park, Dimonika Biosphere Reserve and Tchimpounga Nature Reserve (Congo), Luki Biosphere Reserve (DRC), and the recently gazette Maiombe National Park (Angola). (Figure 1). The situation in DRC, Congo and Angola are peculiar following decades of yet unresolved political and economic instability and high population densities. Thus, in these countries, its forest and ecosystem are subjected to high rates of deforestation and degradation mainly through heavy agricultural activities, illegal logging and poaching ([11,12]). Moreover, the most important oil reserves for Congo and Angola are found here in spite the fact that the poverty of the local populations is high ([5-8]).The Mayombe ecosystem is a home for species of outstanding universal interest, such as two species of great apes – chimpanzee and lowland gorilla ([13-15]). Despite these potentials of the Mayombe Forest, it is virtually unprotected in law or practice in all three countries2. There are several proposals for establishing additional protected area. Previous recommendations3 and proposal made from pioneer conservation efforts in Cabinda indicated the need for joint regional efforts ([8,12]) around the Mayombe area. Two international organisations (denoted as conservation 1 and conservation 2)4 and a donor worked to facilitate the establishment of a Mayombe forest transboundary protected area (Mayombe forest) between these three countries. A project5 entitled: “Forest conservation, environmental cooperation and improved human livelihoods in ecosystems of international importance in the Congo Basin” was identified to start activities. This will be referred to in the subsequent sections as the Mayombe project. The long-term objective of this project include the establishment of a transboundary protected area within which there will be Biosphere Reserve(s) and a regional cooperation mechanism in the southern part of the Mayombe Forest ecosystems between DRC, Congo and Angola.  | Figure 1. Map showing the existing protected areas of the Mayombe Source: [3] |

Negotiations on the Mayombe site gained force around the year 2000 after previous talks between these countries. The year 2000 was mainly for the concept and process initiation and 2002 for initiating transboundary negotiations on cooperation in the conservation of the Mayombe forest ecosystems. Discussions continued on a positive note and the first draft of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was written by a consultant in 2006 alongside the project document6. Information presented here is from the launching activities of the Mayombe project which included the negotiation process of the MOU in 2009/2010. The main aim of the MOU was to design ground rules for further collaboration between the three countries on the establishment of the transboundary area. The article does not include information after March 2010. The results will focus on describing how the negotiation process went while linking it to the phases of multiparty collaboration framework. In this section we shall also talk about the outcome of the negotiation process – the engagements made by the three countries and how this was done. Subsequently, the discussions section links all these experiences to the theories of multi-actor negotiation and collaboration framework and brings out the lessons learnt.

3. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

This section will be on the theoretical framework and methodology. In the theoretical framework, we shall outline the multi-stakeholder negotiation and collaboration phases, processes and the underlying assumptions. On the methodology we shall emphasize the importance of participatory processes and the strengths of expert knowledge in analysing and reporting findings.

3.1. Theoretical Framework

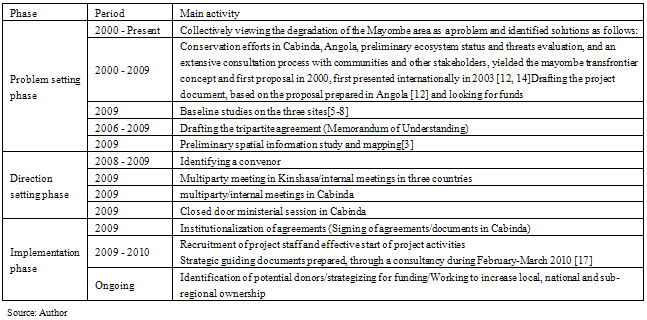

Authors were inspired by the multi-actor collaboration framework[16]. Although this framework focuses on negotiation between users group, it has been adapted to be used for negotiation between national stakeholders. Here, we present the negotiation and collaboration process in terms of issues and stakeholders; the exploration of alternatives; how it culminates in reaching a negotiated agreement and finally the institutionalization of the agreements. In so doing, we used examples from what happened to demonstrate how the theories of negotiation and collaboration processes actually work in practice at the early stages of setting ground rules for a negotiation process. This framework uses a phase model that includes three broad phases namely: problem-setting, direction-setting and implementation phases. In the Mayombe project, these phases are described on table 1. A similar framework brings different actors together and integrates frames in one perspective or solution[10]. Within the Mayombe project, integrating frames in one perspective is concretized by signed documents to indicate commitment and engagement by the diverse group of stakeholders. The underlying assumption of this framework is that all stakeholders work together around a shared issue (the Mayombe forest) as if:• they all have equal or not very contrasting power to influence the decision making process;• although they may maintain different positions, their underlying interests are the same or at least reconcilable;• they all collaborate voluntarily[10].

3.2. Methodology

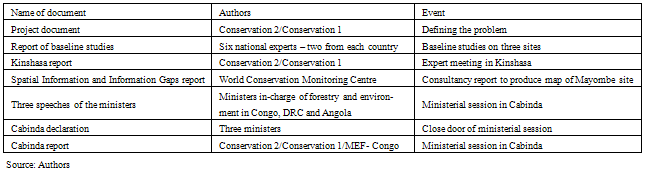

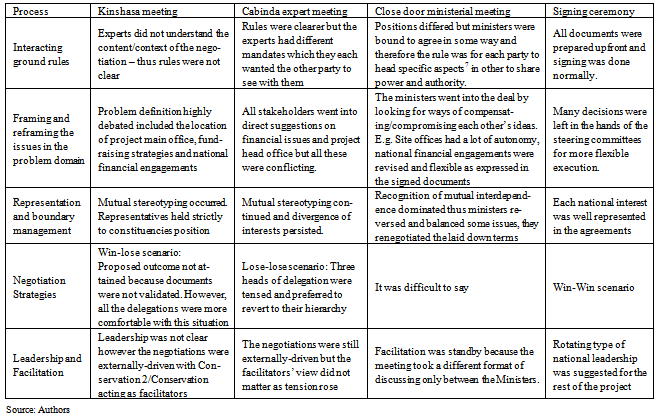

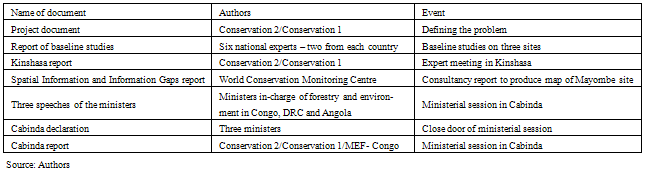

Authors accompanied stakeholders in the negotiation process and were able to map, model, observe, compare and diagram trends and issues through participatory learning and actions. Participatory methods now present depth; richness and realism of information. Since local analysts are usually committed to getting detail, complete and accurate data, from their personal experience, they can interpret change and causality[18]. Authors engendered diverse views used in negotiating the Mayombe project and linked them to theories on multi-actor negotiation processes by using expert judgement, content analysis and field observations. [19] describes this as social learning in participatory processes. In analysing the different rationales/modalities they present, [19]substantiates the strengths of ‘participative methodology’ and notes that they can be theoretical - meaning people don’t change without ‘involvement’; ideological/normative meaning people have the obligation to participate and above all political because of the wish to empower. Thus, authors were focused on capturing how involvement and participation took place and the polities involved in the overall process. In doing so, we monitored for five categories of multi-actor processes as described by[17]: interacting ground rules, framing and reframing, representation and boundary management, negotiation strategies and finally leadership and facilitation. On-stage events involved in the negotiation process were meetings and surveys. These were the various internal meetings, multiparty meetings in Kinshasa/Cabinda, closed door ministerial session in Cabinda and the signing ceremony in Cabinda. Additionally were the baseline surveys by six consultants and a preliminary spatial data analysis survey and mapping. Elsewhere, authors kept close contact with the national focal points, consultants and expert groups to follow-up off-stage processes as impromptu internal meetings, internal/bilateral arrangements and debates. Speeches, reports and other documentations during these events served as the main sources of data. These are summarised on table 2.Results are presented using narratives in tables and boxes. Intentionally, some sensitive details on the performance of stakeholders in the negotiation process will not be reported by country but will be generalized. This will provide a global picture of what happened and readers could attribute details in any of the cases.

4. Processes and Outcome of Preliminary Actions

Putting together the personal experience of authors and information summarized from various data sources; this section presents a situational analysis (problem identification, goal formulation, implementation and outcome) of preliminary actions.

4.1. Problem Setting Phase

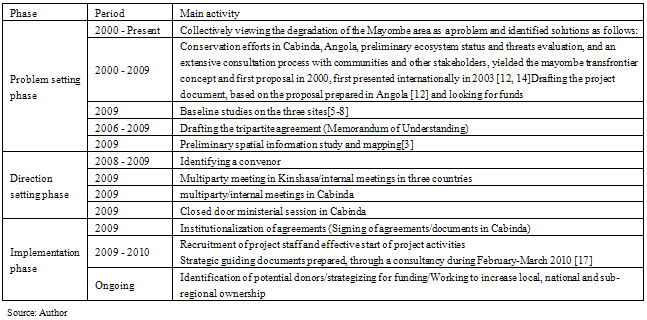

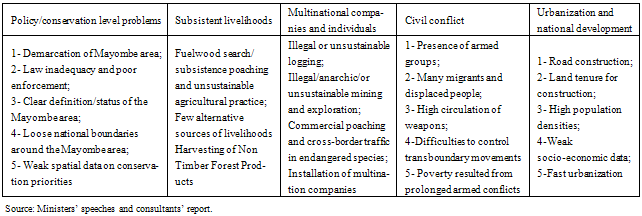

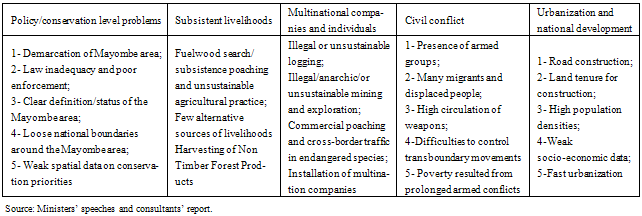

This phase consist of refining the project document, the MOU, the road map and the baseline studies to bring out a common definition of the problem as seen by individual countries and by the region. Then it analyses factors that generate commitment to collaborate and how actors are identified and legitimated. From the project narratives and debates, the problems identified clustered within domains as policy/conservation level problems, subsistent livelihoods, multinational companies, civil conflict, urbanization and national development (Table 3). Table 1. Phase model of multi-actor negotiation process of the Mayombe forest transboundary protected area

|

| |

|

Table 2. Information sources

|

| |

|

Table 3. Problems7 identified in the Mayombe area by domain

|

| |

|

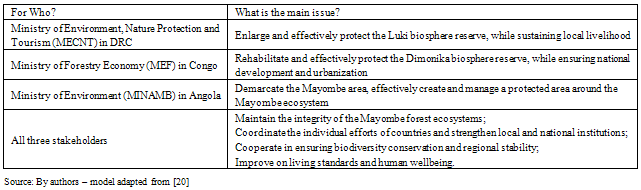

Table 4. Common definition of the problem by by the three governments together and individually

|

| |

|

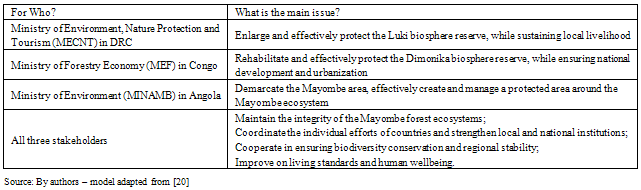

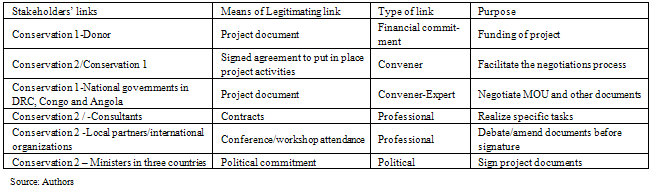

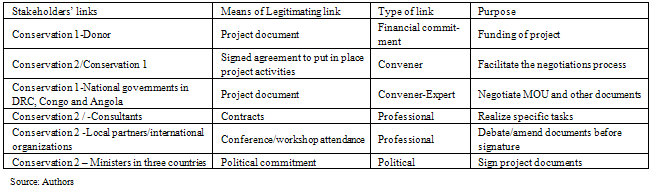

Common definition of the problem: From the ministers’ speeches, the main problem was to maintain and restore the integrity of the Mayombe ecosystem and ensure biodiversity conservation in order to promote regional stability and improve livelihoods of the population (see table 4). Globally, studies showed that there were transboundary movements difficult to control. As such, law application became complex as the migrants hardly respected the laws on another territory and the authorities found it difficult to apply the law on them because it required other bilateral arrangements. Poaching was difficult to control because of the presence of armed groups and the circulation of small arms within family units, as well as networks of illegal cross-border traffic in wild species and in their derivatives. As solution pathways, the spatial data analysis of the area [3] suggests that priority should for example be placed on identifying the remaining areas of intact primary forest that are still available for conservation in the region. This would entail considering existing multinationals such as logging and mining concessions. Detailed maps of such priority areas could be used for stakeholder consultation on the establishment of new protected areas and/or enlargement of existing protected areas. Integrated land use planning will need to be informed by the best spatial information on biodiversity, ecosystem services and socio-economic factors currently available for the region. Finally, it is necessary to think of readjusting the conservation objectives in these reserves in order to face realities.Generating commitment to collaborate: Commitment to collaborate was activated by the problems identified on specific sites as summarized on table 4. In Angola, it was weak application of the law on fuelwood and other forest exploitation activities. Fragmentation of the forest would be detrimental despite specific commercial and other interests in doing so. Delimiting the zone under the Mayombe forest was cumbersome. Therefore deforestation, land degradation and poaching continued to increase at immeasurable rates. It should be noted though, that the highest ecosystem's integrity and biodiversity richness, in the southern part of the Mayombe forest, exists in the Angolan component ([8] and [6]). In DRC, more than 2/3 of the Luki biosphere reserve (RBL) was occupied by agricultural activities and forest concessions. This reserve was characterised by high population density. There were multiple sources of conflicts which resulted partly from the disproportionate attribution of land and a great pressure on the ecosystem resources. The area was enclave and there was a need to re-demarcate the reserve and clarify boundaries. Also law enforcement was weak and application tools were insufficient, obsolete or incompatible with the present state of the art[7]. In Congo, the current situation showed that the area of the Mayombe forest was in a state of advanced degradation due to the presence of more road infrastructures and assets. This situation follows the establishment of a new national road which was close to the central zone. It contributes to the existing pressure on the area resulting from activities of traditional mining and illegal exploitation of timber[5]. Participating countries had a similar history, socio- economic and political tendencies meaning that a joint solution could work similarly for them. In addition, countries like DRC and Congo had stakeholders with specific experiences on the Mayombe ecosystem ([3, 5-8]) that could benefit each other and the other sites. All these were motivating factors that generated the committed to collaborate.Identifying and legitimating relevant stakeholders, and finding a convenor: The Cabinda declaration portrayed national engagement and commitment to collaborate. The MOU was a framework and a formalised basis of collaboration between negotiating parties. It contained many articles describing the modalities of collaboration between parties. This made easier defining actors, rules in the implementation process and could help in redefining the problem jointly and looking for common solutions to benefit all three countries. Through the baseline studies, networking and proposals from national governments, many stakeholders involved with activities on each of the Mayombe sites were identified. These stakeholders fell into categories as: National and local government, regional institutions, development partners (community based organizations, associations etc), Non- governmental organizations (NGO), local communities and municipalities. Some of these stakeholders were invited to the experts’ meeting in Kinshasa and Cabinda while others were to be consulted during field work. In all, most of these partners were consulted by the consultants in doing the baseline studies. Nevertheless, the initiation of the negotiations process was rather externally driven, and characterized by a top-down approach.The initial project was funded by the donor through Conservation 2 who identified Conservation 1 as a facilitating institution. As such Conservation 1 through its forest conservation program based in Yaoundé, Cameroon worked hand in hand with Conservation 2 as a facilitator of the activity. This facilitation process was made easier through Conservation 1’s office in DRC. Present resources for the ignition phase included financial resources from the donor, human and material resources from national governments in all three countries and technical expertises from international conservation organisations. Additional resources were to be mobilized throughout the implementation process of the project. All the stakeholders had different links and relation depending on their purpose, expected action and outcome as summarized in table 5. Conservation 1 as convener represented Conservation 2 on the field. As such, Conservation 1 followed-up, monitored and reported the progress of activities to Conservation 2 as per their signed agreements. Since the main players in the negotiation process were the three national governments, many other internal arrangements took place following their national rules and regulations. This sometimes delayed a step. But since no stakeholder had the right to push the other, all stakeholders including the convener were bound to lobby and encourage the delaying partner to react. The convener played a major rule to coordinate activities and follow-up the actions of each stakeholder through frequent telephone calls, emails and personal discussions when possible.

4.2. Direction Setting Phase

Direction setting involved establishing ground rules, agenda setting, organizing subgroups, joint information search, exploring options and reaching an agreement. The basic rule for the parties was that the ministers in charge of environment had to champion the negotiation process in each country. To do so, a contact person (focal point) had to be appointed by the minister to serve as a liaison between the country involved and other players. Other ministries and administrations had to be contacted and involved to get their own viewpoints nationally. During the expert meeting, at-least three experts per country were to be present although if the country could, more experts could be represented. This is the case of the expert meeting in Kinshasa and Cabinda where Congo was represented by more than ten experts. On the part of the convener, an agenda was set which detailed the main activities and steps to be realized until the signing of the agreements. The convener drafted these steps and circulated them to the national governments for comments and amendments in each case. These activities which helped in organizing the sub groups constituted the terms of reference of conservation 2-the convener. They were: Box 1. Details for direction setting in negotiating the Mayombe Project idea

|

| |

|

Table 5. Dependencies among stakeholders in negotiating the Mayombe forest area

|

| |

|

The main subgroups involved in this process were the consultants, the ministers and the experts. The experts groups were organized through constant internet communication, phone calls and meetings. The consultants’ for baseline studies did not have a lot of relationship between them but they had similar terms of references for data collection and report write up. The main means of communication with the consultants was the internet. The ministers being high level authorities with many socio-political responsibilities, it was difficult coming to an agreement on their schedule. Therefore only the national focal point plus some high authorities in Conservation 2 and Conservation 1 were able to interact with them. However, many informal and off-stage discussions took place which were not registered but influenced the process a great deal. After exploring many options, main agreements reached at during the Kinshasa meeting included:Box 2. Agreements reached at during the Kinshasa meeting

|

| |

|

4.3. Implementation Phase

The implementation phase consisted of 1) the experts reporting the outcome of the Kinshasa meeting to ministers 2) national internal meetings being organized to further discuss the documents 3) the ministerial session being organized and the documents endorsed and signed.Through the final communiqué and the deliverables of the Kinshasa meeting, national focal points were charged with organizing internal meetings, informing the ministers and concerting on their schedule to organize the 1) ministers’ field tour and 2) ministerial session in Cabinda. This was done and could be verified through the speeches of the ministers who congratulated the experts for their tireless efforts to accomplish the negotiation goals. Nevertheless, the field tour could not be organized due to the conflicting schedules of the ministers. Little could be reported on the internal meetings because 1) they took place in the individual countries and was thus very expensive to be attended by the facilitators 2) as a rule in multi-stakeholder negotiation process, internal meetings are suppose to be attended only by constituency members and to an extent other members of the negotiating parties to do some off stage arrangements 3) facilitators were informed of on-going negotiation processes through phone calls and emails and they aided with clarification and advice.Activities during the ministerial session were: a technical meeting amongst experts; a close door session of the ministers and the signing ceremony of the documents. The outcome of the ministerial session was as in box three belowBox 3. Outcome of the Ministerial session in Cabinda

|

| |

|

As a means to build external support, many international organizations, diplomatic missions, ambassadors and donors were invited and took part in the signing ceremony in Cabinda. There were in all eighty high level participants during this event. Although the convener invited these partners, each country made additional efforts to invite partners that they deemed could be of national interest thereafter. In connection with putting in place the project, the head office of the transboundary protected area was located in Point-Noire in Congo. In this case, the project coordinator was not to come from Congo. Next to the head office was to be three national offices located in the three sites. Here, Congo was to start chairing the steering committee meeting which entailed some financial implications. The MOU provided a structure for three steering committees – the ministers’ steering committee, the regional steering committee and the national steering committee. These were to be led by the Ministers one by each, on a rotation basis for a given period of time. The aim was to monitor the implementation of the MOU at the national, regional and international levels.

5. Learning Points on the Way National Engagements and Polities Combine to Guide Transboundary Negotiation Processes

From the beginning, it was noted that this paper presents a process to depict how preliminary arrangements that set the ground rules for further collaboration transpire in natural resource management. These include arrangements that lead to signing the MOU, the Cabinda declaration and endorse the Mayombe project document and roadmap by Congo, Angola and DRC. These documents were meant to serve as guiding principles to be used for future actions in putting in place the Mayombe forest transboudary protected area. Here we present how the events that lead to these outcomes relate to theory in multi-stakeholder negotiation and collaboration to bring out main lessons learnt.

5.1. Relating Experience on Joint Management of the Mayombe Landscape to Theories in Multi-actor Negotiation and Collaboration Processes

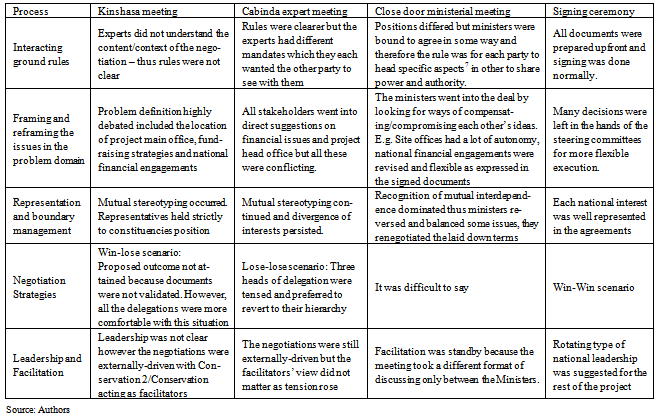

Igniting the Mayombe initiative had six main activities during 2006-2010 – elaboration of project document and MOU based on project concept written in 2000 ([12]); Baseline studies and many internal meetings; Kinshasa meeting; Cabinda expert meeting; close door ministerial meeting and the signing ceremony. The first two activities set the ground work for the various meetings (See table 6). The internal meetings are not elaborated here because these were where each party planned its strategy and they took place in many forms. All multi-stakeholders’ meetings had plenary sessions and group work. Throughout all sessions, national experts always sat together to facilitate group tactics. During the Kinshasa meeting, national experts were split up into three mixed groups following their various areas of competence to discuss the MOU, project document and the stakeholders’ mobilization strategies. The second and third groups were further charged with finalizing the action plan, the road map and the terms of references and the composition of the various steering committees. Because the negotiation process could not be complete, most of these issues were carried forward to be discussed and redefined at the national level and then to be finalized during the Cabinda experts’ meeting. Thus experts stocked to their constituencies and were less willing to concede and compromise. At the national level, each party had many exchanges with the facilitators while defining their national strategies so that they could be able to maintain a more favourable position during the Cabinda meeting. Thus most of the internal meetings were politicized with partners hoping to capitalize their national strength to persuade the other parties to align with them. Such strengths included availability of experience and data on the Mayombe site that could benefit the others, location of their site etc. Even so, in Cabinda, it was difficult to come to a compromise during the experts meeting and so the debates were moved over to the Ministers’ table. This was the main point of discussion in the closed door ministerial session. They finally agreed on the terms of the documents to be signed by accepting to gain and loose something at each point. The processes of this negotiation are summarized on table 6.For their part, apparently not all Conservation 1/ Conservation 2 facilitators were seen by parties to be acting a neutral role. Some were viewed as trying to promote specific interests of specific countries, especially in relation to the headquarters location and budgetary management. This increased tension as well as national commitment. As a solution, in several points of the negotiation process the facilitators were put aside even though this did not stop the accusation from parties in different circumstances. The effects of these accusations were positive as it increased national ownership of the negotiation process and streamlined the intervention of the facilitators shifting the negotiation process from externally to nationally driven. Table 6. Outcome of the negotiation on main processes

|

| |

|

5.2. Lessons Learnt in Negotiating Multi-actor Processes on Ecosystems, Protected Areas and Forest Conservation

Recalling that 1) natural resource management problems are interdependent and transcend boundaries and that 2) improved resource management do not only depend on the cooperation of field stakeholders but also on interstate engagements and regional polities, the following learning points could be underlined from the outcome of this preliminary negotiation process. Such points could guide actual implementation in many ways. Divergence of interest are common but mutual interdependence always dominate: In multi-actor processes, a diversity of norms and rules need to be deliberated and accepted by all. The Mayombe initiative had two main challenges – 1) negotiating the MOU and 2) the pilot activities of the Mayombe project. The experts in negotiating these documents were faced with the challenge of sticking to their national requirements, norms and standards. Even so, national experts had diverging viewpoints. Such interests of partners influenced many processes like changing the agenda of the Kinshasa meeting. Still, in Kinshasa, they were unable to completely revise and validate the required documents – the MOU, the project document, the road map and the stakeholders’ mobilization strategy. However, they all recognized that they needed the MOU signed and activities on putting in place the transboundary protected area started. As such, after the failure to agree in Kinshasa, all three parties had several internal meetings and serious deliberations with the facilitators. This was to help strengthen their position in the negotiation process. Since they all worked at almost equal rates during these internal meetings and off stage negotiation processes, the negotiation during the experts’ meeting in Cabinda turned out to be a lose-lose arbitration. After an all-night conciliation, focal points and experts were so tense at this stage and had urgent internal meetings to agree on what to go and report to their national authority – the Minister. Despite all this, the closed-door Ministerial session took longer than expected. However, the ministers finally concluded on the crucial points and agreed to go ahead with the signing ceremony. Observations here show that a) negotiating and putting in place a protected area needs an interaction between a multiplicity of national players whom within themselves have specific interests; b) outcome of internal meetings were far different from the expectations of the multi-actor forum and thus made heavy the whole process; c) there was knowledge gap between experts from the same country even though each country was supposed and assumed to have prepared its experts upfront through internal meetings; d) the negotiations process initiated as externally-driven by Conservation 1/Conservation 2 facilitators, while the facilitators were not all synchronized with each other, and not all were viewed as impartial by the negotiating parties; and e) In all, ecosystems negotiations processes are cumbersome and bulky at the national and regional levels. This is what[21] describes as chaos and order entwined in the dynamic nature of ecosystems. [18]noted that the chaos theory leads to a clearer understanding that patterns and directions of change can be sensitive to small differences in starting conditions. Thus, differences in information, power positions and national preparedness were important factors that caused divergence of interest. However, the need for improved livelihoods and natural resource conservation were push factors that called for synergy.Funding and signed documents are necessary and could stimulate real action: The idea of a Mayombe transboundary area between these three countries started far back in 2000. Most of the arrangements have been through correspondences and ‘tete a tete’ discussions, exchange of information, and consultations with a range of stakeholders. These actions created the basis for negotiating cooperation between the countries. Recently with the funding, based on the project document and with the need to sign the MOU, interactions became more active. This prompted each national player to get more engaged in the process and follow-up the baseline studies more keenly. Although the suggested funding was not enough to put in place the transboundary protected area, national stakeholders were more motivated and ready to make the project a reality. After the signing of the MOU, the project staff were recruited and an office space identified. These are all evidence of real action – thanks to the MOU that laid down ground rules. Multi-actor processes need to be very flexible and off stage arrangements are strategic push factors: All documents for validation and signature were prepared upfront by consultants and agreed upon by national experts separately. For this to become a reality, many things were readapted. For example, first, although all negotiating parties validated the Kinshasa agenda, during the meeting, national experts at each point concerted and came up with new ideas which at one point ended up in changing the agenda for days two and three. Even so, the negotiation outcome ended up in a win-lose situation. Each national team was satisfied that they did not let go their point and believed that the other parties will take their concern into consideration during the next meeting. Secondly, a ministers’ field tour was planned to be executed after the Kinshasa meeting to meet other local experts. Experiences from the Kinshasa meeting, the internal meetings and the complicated schedule of the ministers, showed that the main issue on negotiating the MOU was not the field actors but national and regional polities. Thus, for success, emphasis had to be laid on information sharing and cross- border dialogue. As such the whole negotiation framework was refocused. Finally, during the Cabinda experts’ meeting, constituency members remained stereotyped and focused on their position. Following the rigidity observed and in order to change positions, urgent internal meetings were convened in the night to readapt their strategy and position. This is what helped in informing the Ministers during the close door ministerial session.Internal Meetings need to be taken more seriously: Initially there were signs that internal meetings were not well prepared. Thus outcomes during the Kinshasa meeting were far from expectation because 1) stakeholders did not master the project document and terms of the MOU upfront, 2) stakeholders were only interested in defending their national interest without considering the time frame for the discussions 3) Some countries had a better knowledge of the issue than others 4) some stakeholders had a stronger national political influence than others - thus their opinions dominated and biased the discussions. With the results of the Kinshasa meeting, internal meetings were reinforced and during the Cabinda experts’ meeting, national stakeholders from each country spoke the same language. However, the negotiation process became more severe. This is because each group of national actors thought their position was clearly understood by the others in Kinshasa - which was not right. To sort this out, impromptu internal meetings were held in Cabinda to enable the experts agree on which ground rules to change taking into consideration the position of the other experts as well as the opinion of the respective ministers. Even so, internal meetings were unable to complete the negotiation process. Therefore, the three ministers had to go into a closed-door ministerial session which took longer than planned. This indicates that the negotiation process between the ministers was also very intense. All in all, internal meetings within each constituency are very vital in addressing conflicts of interest and the opinion of high level authorities are overriding. Leadership and Facilitation is important but can be cumbersome and very expensive in transboundary negotiation process: The experience in the Mayombe forest transboundary initiative is that leadership and facilitation could be made cheaper by the use of new communication technologies like internet and telephone discussions. However, this means that the facilitators should have strong understanding of the guiding principles of multi-actor processes and the ground rules of the negotiation. Elsewhere, this is good as it allows for each party to build their internal strategies uninfluenced. Rise in tension when well managed by facilitators is a good development. It allows for the facilitators to remain neutral and provokes a shift from an externally-driven to national/regional ownership of the negotiations process, which could eventually lead to a win-win scenario.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Stakeholders from Congo, DRC and Angola worked together around the shared issue of the Mayombe forest following the underlying assumption of the multi-actor collaboration and negotiation framework [10] However, experts all had contrasting power to influence outcome. In the process described in this paper, national commitment was made tangible by participating in the negotiation meetings and signing the documents. We notice that after every other multiparty meeting, temperaments changed, divergence increased, but participation was reinforced. This made the negotiation process tougher but more binding as each member of the negotiating team was very interested to see that they come to an agreement even though none of them was willing to give up their position. Consequently, experts’ negotiations turned out to be win-lose and lose-lose scenarios from the 1st to the 2nd meeting. The intervention of the ministers, resulting with a shift from the preliminarily externally-driven negotiations process, to increased national/regional ownership, lead finally to a win-win scenario. This means that negotiating transboundary protected areas have multilevel power positions and decision making that must be considered, and that regional, national and indeed local ownership of the process are essential. Sometimes, it needs the help of high level authorities to come to a compromise as was the case here, in which only the Ministers were able to conclude on the documents to be signed.Although negotiating parties may maintain different positions, their underlying interests were the same and they all collaborated voluntarily to ensure that this first step of setting ground rules to guide the putting in place of the Mayombe forest transboundary protected area was successful and well-presented and represented of the three constituencies. As such, they often organized impromptu internal meetings to agree on crucial issues. Accordingly, we found that, in negotiating rules for transboundary protected areas, basic points of emphasis should be to identify reconcilable interests and use these as entry points. In this way, stakeholders will deliberate on common goals and divergence of interest will be limited. In the Mayombe project, this was done through the upfront project document, baseline studies and the spatial analysis study. Even though tension was still high, results of these studies helped a great deal in clarifying technical issues and convincing stakeholders to share a common vision. This means that written materials are essential to facilitate negotiation processes.Now that the documents have been signed and endorsed, the project facilitators have guiding principles on how to put in place the Mayombe forest transboundary protected area between Angola, DRC and Congo. One thing to be verified in the cause of the project will be how these rules really work in practice, what was changed and why, and what was adopted and how it affected the implementation process. Also, it will be interesting to follow-up and analyse how field stakeholders perceived and respected the signed documents, and how their views are to be incorporated in the decision making process. Globally speaking, in putting in place transboudary projects, efforts should not be limited to technical considerations but rather be inclusive of polities, grassroot issues, technical aspects and national, regional and international agendas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript is an output of a project funded by the Norwegian government. The authors will particularly want to thank and salute the governments of the three countries for involving them in this work and making available information on the negotiation process that started since 2000. We acknowledge the inputs and interaction of experts and participants during the meetings which have resulted to this manuscript. We wish to thank IUCN and UNEP for co-opting authors as consultants on this project which gave them the opportunity to gather data for this manuscript. Finally, we wish to thank Serge Bouda (UNEP) and Sadia Demarquez (IUCN) for facilitating the project processes as well as Ngome A.F. and Nchinda V.P. both of IRAD for valuable contributions on the manuscript style and presentation.

Notes

1. Located between Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Congo2. Analysis presented in Consultants’ report 2010 [17]3. As stated in the speeches of the three ministers4. The names of these organisations as well as the donor have been withheld for confidentiality reasons5v. The project document was based on a proposal and documents produced during 2000-2004 through extensive participatory work done in Cabinda, Angola[12, 14].6. The initiative was first proposed in 2000 following a pioneer conservation work in Cabinda, Angola [12, 14]; negotiations initiated between Angola and R Congo in 2002.7. It should be noted that there are significant differences in ecosystem’s integrity and endangered species’ survival, between the different components of Mayombe forest, with several “conservation islands” (e.g., in Cabinda and in the northern part of the Mayombe ecosystems)Pahl-Wostl, C. (1995) The Dynamic Nature of Ecosystems: Chaos and Order Entwined. Chichester: Wiley.

References

| [1] | Helle M. R. and O. Westermannb, (2002). Understanding Interdependencies: Stakeholder Identification and Negotiation for Collective Natural Resource Management. Agricultural Systems 73 41–56. |

| [2] | Herbst, (2000). States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control Princeton. N.J.: Princeton University Press. |

| [3] | Bomhard B., I. Lysenko and A. Cottam (2009). Ecosystems, Protected Areas and Conservation Priorities in the Mayombe Forest: An Analysis of Spatial Information and Information Gaps for the Mayombe Forest Transboundary Initiative WCMC/UNEP. |

| [4] | de Wasseige C., Devers D., de Marcken P., Eba’a Atyi R., and Mayaux Ph., (2009. The Forest of the Congo Basin. State of the forest 2008. Luxembourg: Publication office of the European Union, ISBN 978-92-79-13210-0, doi: 10.2788/32259 |

| [5] | Diamouangana J. and Mizingou J. (2009). Etat des Lieux sur l’Initiative Transfrontalière de la Foret du Mayombe au Congo (Site de Dimonika) Congo (Baseline Study on the Mayombe Forest Transboundary Inititiative in Congo - Dimonika site. |

| [6] | Miguel X. (2009) Ecosystème naturel de Maiombe (Synopse de la situation actuelle) (Mayombe natural ecosystem (Synopsis of the actual situation) Cabinda, Angola. |

| [7] | Nyimi M., and F. Kapa (2009) Etat des Lieux de la Partie Congolaise (R.D.Congo) du Massif Forestier du Mayombe dans une Perspective de Coopération Transfrontalière Visant la Création d’une Aire Protégée Tri-nationale (R.D.C, Congo et Angola) (Baseline studies on the Congolese part of the Mayombe Forest in the Perspective of Transboundary Cooperation for the Creation of a Tri-National Protected Area). DRC |

| [8] | Ron T. (2009) The Maiombe Forest, Cabinda, Angola: Within the Framework of the Maiombe Forest Transfrontier Conservation Initiative – Site Report. Cabinda, Angola. |

| [9] | CEFDHAC, (2004). Gouvernance et Partenariat Multi-Acteurs en Vue d’une Gestion Durable des Écosystèmes Forestières d’Afrique Centrale (Governance and Multi-actor partnership for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa). Actes de la 5éme Conférence sur les Écosystèmes de Forets Dense et Humides d’Afrique Centrale (CEFDHAC) Proceeding of the Fifth Conference on the Dense and Moist Forest Ecosystems of Central Africa. Yaounde, Cameroon 24 to 26 May 2004. |

| [10] | Craps, M., Dewulf, A., Mancero, M., Santos, E., & Bouwen, R. (2004). Constructing Common Ground and Re-creating Differences Between Professional and Indigenous Communities in the Andes. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 14, 378 - 393. |

| [11] | Dezoysa, N., Pangou S.V., Scott Tompsett S. (2004). Effects of Soil Properties on growth of Young Tree Seedling in Logged – Over Tropical Rain Forest in Mayombe Congo. Journal of the Soil Science 58(2) : 1768-1772. |

| [12] | Ron, T. (2003) The Conservation of the Mayombe Forest, Cabinda, Angola, within the Framework of a Transfrontier Conservation Initiative. Paper presented at The World Parks Congress, September 2003, Durban, South Africa. |

| [13] | Pangou S.V., (2006) Effets de l’Exploitation Forestière sur la Dynamique de la Flore dans le Mayombe (Congo). Ann. Univ. M. Ngouabi : 7(3) : 32- 46. (Effects of Forest Exploitation on the Mayombe Floral (Congo). |

| [14] | Ron, T. (2005) The Mayombe Forest in Cabinda: Conservation Efforts, 2000-2004. Gorilla Journal – Journal of Berggorilla and Regenwald Direkthilfe, 30: 18-21, published in English, French and German(http://www.berggorilla.de/gj30e.pdf). |

| [15] | Schwartz D., Lanfranchi R., Mariotti A. (1990) Origine et évolution des savanes inter mayombiennes (R. D. du Congo). Apports de la pédologie et de la biochimie isotopique (Origin and evolution of the inter-mayombienne Savanna (DRC). Soil and isotopic biochemistry contribution (14 C et 13 C) in Lanfranchi R and Schwartz D. (éds.) Paysages quaternaires de l’Afrique Centrale (Quarterly landscape of Central Africa, ORSTOM, Paris:314-325. |

| [16] | Dewulf A. (2007) An Introduction to Multi-actor Processes. Introductory Text for the IOB Masters Module “Multi-actor Processes”. Unpublished paper. |

| [17] | Ron, T. (2010) Mission Report and Six Related Strategic Documents and Concepts. Mayombe Project. Point Noire Congo. |

| [18] | Chambers, R. (1994). Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): Challenges, Potentials and Paradigm. In World Development. London, Elsevier Science Ltd., Vol. 22., n°10, pp. 1437-1454. |

| [19] | Leeuwis, C. (2000) “Reconceptualizing Participation for Sustainable Rural Development: Towards a Negotiation Approach”, Development and Change, 31, pp. 931-959. |

| [20] | Dewulf A, Marc C and G Dercon, (2004). How Issues Get Framed and Reframed When Different Communities Meet: A Multi-level Analysis of a Collaborative Soil Conservation: Initiative in the Ecuadorian Andes. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML