O. R. Adeniyi

Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension,Bowen University, P.M.B.284, Iwo, Osun State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: O. R. Adeniyi , Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension,Bowen University, P.M.B.284, Iwo, Osun State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

A cost minimization linear programming model was used to select some locally available feeding stuff as substitute for the conventional infant foods. The use of 58% white maize; 41% groundnuts and 1% Soyabean meals was optimum in formulating a good substitute for the conventional infant food based on the data available in Nigeria. At an estimated cost of ₦399.25 per pack of 450 gramme weight, the formulation was more than four times cheaper than the least priced commonly marketed tinned baby foods on- shelf in Nigeria. Sensitivity analysis of the linear programming solution on input costs and industry standards indicated that a good quality infant food substitute can be compounded at minimum costs while sourcing the needed proteins and other ingredients from plant origin. This result is important in view of the relative abundance of cheap local grain legumes in the study area. It is also in favour of the Federal Government policy which encourages patronage and use of local produce.

Keywords:

Linear Programming (LP) Model, Feeding Stuff, Conventional Infant Food Pack, Industry Standards Formulation

Cite this paper:

O. R. Adeniyi , "Cost and Quality Optimization of a Weaning Diet from Plant Protein, Corn Flour and Groundnut Using a Computer-aided Linear Programming Model", International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 41-45. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20120201.07.

1. Introduction

Breast milk is the best and most preferred feeding for newborns (Jelliffe and Jellife 1978). Most of the conventional infant formulas on display in shops and supermarkets in Nigeria are advised to be used to replace or supplement breast milk (Jellife 1968).However, when deciding on how to compound rations to feed the baby well considerations have to be given to the cost of formular, availability of ingredients, health of the baby and the average baby’s body requirements (Akinrele and Edwards 1971).In the face of continually rising prices and the scarcity of conventional baby foods in our markets, an effort aimed at getting substitutes that could be compounded using the locally available and readily abundant feeding stuff was considered a positive step towards coping with the rising domestic demand of nursing mothers. An average infant food of 450 gramme net weight of powdered milk that could be purchased for about ₦4.50 in 1980/81 rose to ₦27.50 in 1990/91, ₦62.00 in 1992/93, ₦100 in 1995 and ₦1,000 in 2001.It currently sells on the average for ₦1,760 in Urban markets. This is a situation of more than 35,000 percent increase in about 30years and 75 percent in the last 10 years.Worse still, the high protein baby foods such as Complan and Cassillan presently sell for between ₦2,500 and ₦3,600 respectively in most city shops when found available on-shelf. In 1985, the prices of these protein supplements were less than ten Naira. With this dramatic trend of upsurge in ‘baby food’ prices, most of the ‘common’ baby foods are being removed from the reach of low and medium income groups in Urban cities let alone the overwhelming majority of the less privileged rural women with relatively low income. If this situation is not urgently arrested, malnutrition, underfeeding and other various nutritional deficiency consequences may worsen the current food crisis situation and increase the rate of occurrence of Kwashiorkor and infant mortality among rural nursing mothers in Nigeria.A solution that appears feasible, however, is to direct efforts towards exploiting the resources of locally available and abundant feeding stuff to compound very simple infant formulas that can conveniently substitute for the conventional baby foods used by our nursing mothers (Ige and Ilori 1990).In this paper, using data collected from households and market surveys in Oyo, Osun and Ondo States of South Western Nigeria together with the results of laboratory analysis of the nutrient composition of selected feeding stuff, an attempt was made to formulate a suitable least cost infant formula that can be substituted for our conventional baby foods using linear programming (LP) and sensitivity analysis techniques (Fashakin et al 1991).

2. Materials and Methods

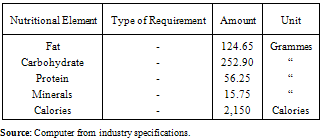

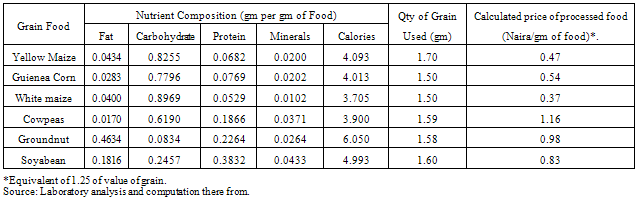

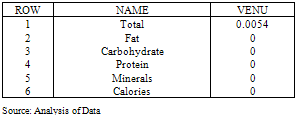

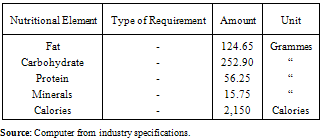

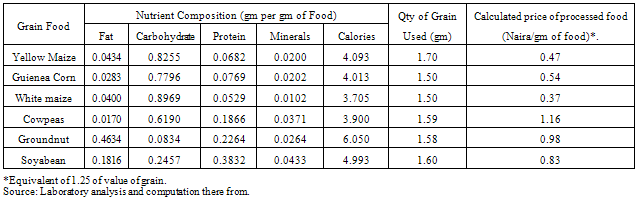

One of the basic assumptions for this study is that the ‘professional’ information as regards the nutrient composition which is normally displayed on containers of baby foods and commercial preparations (like NAN, SMA, Cow and Gate, Rabeena, etc) purchased in our markets has taken into consideration the average child’s survival, optimal health and nutritional requirements based on age. Another is that milk and milk-cereal foods could be fed to infants up till the age of 12-15months, the former mostly used for the first four to six months and the latter afterwards (Fashakin and Ogunsola 1982). Also, analysis in this study was based on calculated digestible true nutrients as contained in the dry matter of processed feeding stuff concerned. It regards that all stages of preprocessing of the foods have been completed up to that stage before being fed to infants in the proportions recommended by the analysis. For example, corn powder is produced from flint corn, steeped in cold water, wet milled, sieved to remove the hulls and fermented naturally for about 24 hours before being over-dried. Soyabean powder is derived from grounded oven-dried decoated soyabean paste, (Akinrele et al 1970) and so on.The Linear Programming ModelLet n be the number of available grain foods, Pj the unit price of food j; Xj the quantity of food j required in the infant formula, m is the number of constraints, bi the quantitative requirement or limit set by the ith constraint and aij, the contribution of one unit of grain food j towards meeting the ith quantitative requirement or limit.We therefore minimize:n Pj Xj (j = 1, 2.n)j = 1(Pj; Xj > 0 for all j’s)Subject to: 1) n Xj = 450 grammes j = 1and,2) m aijXjbi (i =1,2,m)i = 1 (ai, bi > 0 for all i’s)The model has m = 5 and n=6. The six eligible grain foods based on ready production on Nigerian farms included cowpea seeds, groundnut seeds, soyabeans, yellow maize, guinea corn and white maize. The first three of these are major protein sources and the rest are carbohydrate sources. The five constraints embody the required nutrient specifications including fat, carbohydrate, protein, minerals and calories (see table 1).The problem then is to select a set of quantities of foods that will meet nutritional and conventional specifications of infants at the least cost. The principle followed is to restrict choice to ‘popular’ foods among nursing mothers in homes in the study area. For the most part, the values shown in Table 1 represent the more optimistic averages of the allowances recommended for babies as specified in proximate analysis tables of major infant foods sold in Nigerian markets. The 450 grammes weight mark is chosen since most of the conventional baby foods are packed in 450 gramme net weight measure and sold at the observed market price. The list of major infant foods and their current prices were compiled on the basis of reports of actual baby food purchased by 300 consumer families in different parts of Osun, Oyo and Ondo States during the January-October period of 2010. The prices of these baby foods from 1980 till October 2010 were compiled from sales records of major ‘cooperative’ retail shops and supermarkets in the States’ major cities of Iwo, Ile-Ife, Osogbo, Ibadan, Ondo and Akure towns. Any baby food ‘consumed’ at some time during the specified period by at least 60 percent of the sampled families is in the list (Smith 1959). However, the list does not include foods consumed by babies above 12 months old.Table 1. Average Nutritional Content (Requirement) of 450 Gramme Weight Powdered Infant Food

|

| |

|

Table 2. Average Nutritional Composition and Prices per gramme (gm) of Selected Grain Foods (as Calculated Digestible Nutrients)

|

| |

|

| Table 3. Prices of selected Grain Foods for January-October, 2010 (Naira per 100gramme weight) |

| | Grain Food | Jan | Feb | Mar. | April | May | June | July | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Average | | White Maize | 18.50 | 20.00 | 18.50 | 23.08 | 19.23 | 18.46 | 18.46 | 20.00 | 20.00 | 20.00 | 19.62 | | Yellow Maize | 21.00 | 21.00 | 21.00 | 24.62 | 22.30 | 21.54 | 21.54 | 22.50 | 22.50 | 22.00 | 22.00 | | Guinea Corn | 18.79 | 18.79 | 18.79 | 18.66 | 18.65 | 18.65 | 18.65 | 18.40 | 18.79 | 18.79 | 18.68 | | Groundnut | 48.15 | 48.15 | 48.15 | 50.37 | 52.80 | 52.00 | 52.00 | 48.20 | 49.15 | 49.15 | 49.71 | | Cowpea (Brown) | 59.25 | 54.43 | 59.25 | 59.25 | 59.25 | 59.00 | 59.25 | 54.40 | 59.24 | 59.25 | 58.15 | | Soyabean | 42.30 | 42.30 | 42.30 | 41.48 | 41.04 | 40.74 | 40.74 | 40.74 | 42.30 | 42.30 | 41.55 |

|

|

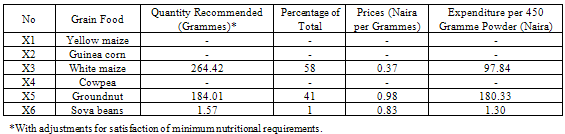

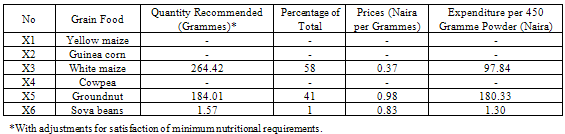

Table 4. Linear Programme Solution for Infant Foods

|

| |

|

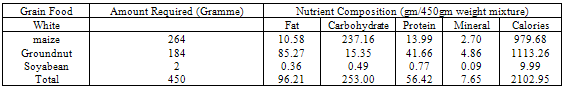

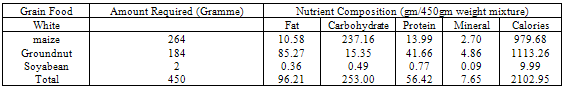

Table 5. Nutrient Composition Values of L.P. - Recommended Mixture

|

| |

|

The data giving the nutritional composition of each of the grain foods and their recommended mixtures were obtained from analyses carried out on these foods by the Departments of Food Science and Technology of Bowen University in Iwo and Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. The laboratory results on single grain foods were compared with those obtained by other researchers (Akinrele et al 1970, Bailey et al 1935, Banigo and Miller 1972, Carter and Hopper 1942, Leclerk and Barley 1917, Schneider et al 1953 and Oyenuga 1959). The values used for the current analysis are the averages computed from those obtained by different researchers and the result of the current laboratory analysis. These values are presented in Table 2.It should be noted that these values allow for losses in nutritive value during cooking and/or drying only; they do not allow for other forms of wastes in processing. The prices of selected grains as used in the model are averages of the prices actually paid by the members of the consumer families during the January-October period of 2010.(see Table 3)For each month, a weighted average price was computed for each grain food by dividing the total expenditure by the total quantity purchased instead of the total quantity consumed since the latter may include gifts, etc. The unweighted average of these monthly averages (their sum divided by their number) was taken as the average price for the period considered. Processing cost of each grain food was taken to be 25 percent of its purchase price. Costs of other inputs such as packaging materials, labour and processing time involved in value addition to make the product in the marketable form were assumed to be 5 percent of shelf price.The Linear Programme (LP) was solved using microsolve LP software (Jensen 1983).

3. Result and Discussion

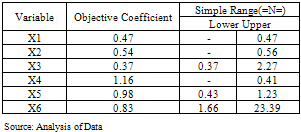

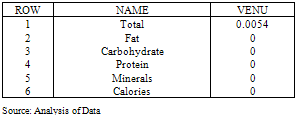

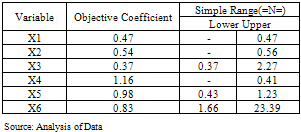

a) Linear Programming Results.Table 4 shows the linear programming (optimum) solution for the least cost combination of grain foods that can substitute for the common infant foods in the study area.The model provides an infant formular comprising of 264 grammes of processed white maize, 184 grammes of groundnut and 2 grammes of Soyabeans meals. On percentage basis, this model recommends that a mixture of about 58 parts of white maize meal, 41 parts of groundnut meal and 1 part of soyabean meal could form a good food substitute for meeting the nutritional as well the conventional specifications infants. The cost was about N399.25 per 450 grammes weight of powdered meal, after giving allowance for processing, packaging and labour. At this estimated cost, the formula is about four and a half times cheaper than the least priced commonly marketed baby foods in Nigeria for the year in question. The nutrient value of the mixture as recommended in the Linear Programming solution shows that the essential basic nutrients of fat, proteins and calories required for growth and development of infants as contained in the industry standards of conventional infant foods could be met at this observed cost.( see Table 5 )Although the mineral content of the formular is low, a judicious intake of iron-based children multivitamins could be recommended as a complement for infants placed on this diet. This is not however peculiar to this recommended formular. It is a common practice for nursing mothers even when children depend mainly on breast milk (Ebrahim 1983).b) Stability of the L.P.-advised formularIn the formulation presented in Table 6, the dual variables for fat, carbohydrate, proteins, minerals and calories were zero each. This implies that there would be no cost advantage to reducing the minimum requirement for those nutrients.The sensitivity analysis performed on the basic solution by varying the coefficients of the objective function and the right hand side of the constraints indicated that the selected mix will remain valid if the costs per gramme of meals of white maize, groundnut and soyabeans do not rise beyond ₦2.27, ₦ 1.232 and ₦23.39 respectively (see Table 7).Table 6. The Dual Solution for Infant Food Formulation

|

| |

|

Table 7. Simple Ranging For the coefficients of Objective Function In the L.P. Formulation

|

| |

|

| Table 8. Simple Ranging For the Right Hand Side (RHS) of the Constraints in the L.P. Formulation |

| | Constraint | RHS | Simple Lower | Ranging Upper | | Total | 1 | 0.804 | 1.003 | | Fat | 0.277 | 0.214 | - | | Carbohydrates | 0.562 | 0.559 | 0.755 | | Proteins | 0.125 | 0.124 | 0.223 | | Minerals | 0.035 | 0.017 | - | | Calories | 5 | 4.668 | 1.0066 |

|

|

This is an interesting result because, although inflation on food prices is a common phenomenon, the upper limits of prices as set above represents unusual increase of about 514%, 26% and 2,719% respectively in the current prices of white maize, groundnut and soyabeans. This result is also striking because the cost of marketed baby foods has increased further since data collection was completed; some have currently had their prices increased by almost 10 percent and this trend is expected to continue because of the foreign exchange needed for procuring ‘tinned’ foods.Table 8 reports the simple ranging for the right hand side of the constraint for the formulation.Results show the range at which technological specification of the mixture could be allowed to vary, keeping others constant without necessarily including non-optimal grains in the mixture. For instance, carbohydrates can vary between 56 and 76 percent while proteins can vary between 12 and 22 percent; fats and minerals can vary from 21 percent and 2 percent respectively to higher percentages without having to include other grain sources of these nutrients.White maize, groundnut and soyabeans are available locally, therefore, the optimum combination of these grain meals without the addition of imported ingredients is most appropriate to the government policy which encourages the use of locally available and relatively cheap sources for essential items of household need being currently imported.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study suggested that it is possible to obtain mixtures of locally available grain meals that could be cheap and substitute for the conventional infant foods and also meet commercial standard using a cost minimization linear programming model. The mixture could be obtained from 58 percent (57.5 percent 100 gramme weight) of white maize meal, 41 percent (40 parts) of groundnut meal and 1 percent (2.5 parts) of soyabeans meal. This result favours the Federal Government policy which encourages the use of cheap and locally available inputs.

References

| [1] | Akinrele, I. A. and Edwards, C. C. (1971): An assessment of the nutritive value of maize soya mixture (soy-ogi) as a weaning food in Nigeria. British J. Nutr. 26: 177 – 185) |

| [2] | Akinrele, I. A: Adeyinka, O: Edwards, C. C.; Olatunji, F. O.; Dina, J. A. and Koleoso, O. (1970): The development and production of soy – ogi, a corn based protein food. Research Report No. 42, Federal Institute of Industrial Research, Osodi, lagos. P.63 |

| [3] | Bailey, L.; Carpen, R. G. and LeClerk, J. A. (1935): The composition of soybeans and soybean flour and soybean bread, cereal chemistry, 12, 441 – 472 |

| [4] | Banigo, E. O. I and Miller, G. H. (1972): Manufacture of ‘ogi’ (a Nigerian fermented cereal porridge) comparative evaluation of corn, sorghum and millet. Canadian Inst. Food Sci. Tech. 5: 217 – 221 |

| [5] | Carter, J. L. and Hopper, T. H. (1942):Influence of variety, environment and fertility level on the chemical composition of soybean seed. USDA Tech. Bul. 787, 1 – 66 |

| [6] | Ebrahim, G. J. (1983) : Nutrition in mother and child Health Macmillan Press Limited, London. P. 16 – 24 |

| [7] | Fashakin, J. B. and Ogunsola, F. (1982): The utilization of local foods in the formulation of weaning foods. J. Tropical Paediatrics, 28, 93 – 96. Fashakin, J. B.; Ilori, M. O. and Olanrewaju, I. (1991): Cost and quality optimization of a weaning diet from plant protein and corn flour using a computer aided Linear Programming Model. Nigerian Food Journal 9, 123 – 132 |

| [8] | Ige, M. M. and Ilori, M. O. (1990) Oilseed meals as a potential solution to protein dietary shortage in Nigeria. Technovation. International Journal of Technological Innovation and Entrepreneurship U. K |

| [9] | Jellife, D. B. (1968): Infant nutrition in the sub-tropics and tropics. World Health Organisation, Monograph Series No. 291, Geneva. |

| [10] | Jeliffe, D. B. and Jelliffe, E.F.P. (1978): Human milk in the modern world. Oxford University Press Pp 35-40 |

| [11] | Jensen, LP. A. (1983): Microsolve / Operations Research. Introduction to Operations Research (Software Package) Holden Day – Inc. New York pp.99 – 366) |

| [12] | LeClerk, J. A. and Barley, L. H. (1917): The composition of grain sorghum kernels. J. Am. Soc.Agron. 9, P.1-16 |

| [13] | Oyenuga V. A. (1959): Nigerian’s Foods and Feeding Stuffs. Their Chemistry and nutritive value, Ibadan University Press. P. 36 – 44 |

| [14] | Schneider, B. H.; Beeson, K. C. and Lucas, H. L. (1953): Nutrient Composition – corn in the United States. Agr. And Food Chem. 1,172-177 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML