-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2012; 2(1): 30-34

doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20120201.05

Exploring the Link between Land Fragmentation and Agricultural Productivity

Okezie Chukwukere Austin 1, Ahuchuogu Chijindu Ulunma 2, Jamalludin Sulaiman 1

1Economics Section, School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 USM, Penang, Malaysia

2Department of Agricultural Economics, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, P.M.B. 7267 Umuahia, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Okezie Chukwukere Austin , Economics Section, School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 USM, Penang, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The traditional land tenure system in Nigeria coupled with increasing population encourages land fragmentation with attendant consequences for agricultural productivity and commercialization. This study quantified the degree of land fragmentation and its consequences on arable food production. The study makes use of data from 125 farm households spread across the 12 communities in Umuahia-North Local Government Area (LGA) of Abia State, Nigeria. Using Janusezwski index, the study quantified the degree of land fragmentation. The Cobb-Douglas (CD) and the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) were used in exploring the impact of land fragmentation on arable crop productivity. The mean fragmentation index is 0.55 with a variance of 0.02. The average farm size cultivated is 2.68 hectares. Majority of the households (71 percent) clustered around the mean fragmentation index. The results of the CD and GLM show the negative impact of land fragmentation on agricultural productivity. Labour in the CD model remained the single most important factor of increasing productivity. The GLM show that cultivating farms further away from the homestead will lead to higher productivity. The study recommends cooperative farming to enable the farmers to adopt productivity improving farm technologies.

Keywords: Land, Fragmentation, Janususzwski Index, Agriculture, Productivity

Cite this paper: Okezie Chukwukere Austin , Ahuchuogu Chijindu Ulunma , Jamalludin Sulaiman , "Exploring the Link between Land Fragmentation and Agricultural Productivity", International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 30-34. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20120201.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Land fragmentation has been a prominent feature in many countries since at least the 17th century (Tan, 2005). The existence of fragmented landholdings is regarded an important feature of less developed agricultural systems (Van Hung et al., 2007; Hristov, 2009). It can be a major obstacle to agricultural development, because it hinders agricultural mechanization, causes inefficiencies in production, and involves large cost to alleviate its effects (Najafi, 2003; Thomas, 2006; Thapa, 2007; Tan et al., 2008). In view of these considerations, numerous land consolidation and land reform policies have been implemented to reduce fragmentation in European countries like the Netherlands and France, in African countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and elsewhere (Sabates-Wheeler, 2002; Sundqvist and Andersson, 2006).Extant literature has expressed the concern of reknown scholars (Fabiyi, 1984; Olayiwola and Adeleye, 2006) on the problems of traditional land tenure system in Nigeria. The expression of the scholars with respect to the problems of land tenure could be interpreted based on the duplicity of ownership of land with consequent excessive transactioncosts, fragmentation of land into uneconomic sized tracts, and inalienability of land which makes land part of the physical capital but not a part of financial capital. In Africa, land tenure system has generally been broadly described as rigid, creating obstacles in the way of development. Solutions to the land tenure system have involved the adoptions of some institutional changes such as the promulgation of legislation or the adoption of some revolutionary principles. In Nigeria, the intervention into the land problem involves the promulgation of the 1978 Land Use Act. The act has been designed to deal with several problems encountered by the various operative on land since colonial timesLand fragmentation at the household level depends on external policy and market factors, agro-ecological conditions, and farm household characteristics. The resulting level of fragmentation, together with external factors, agro- ecological conditions and farm characteristics, affects agricultural production. In this study, we consider land fragmentation as a phenomenon existing in farm management. It exists when a household operates a number of owned or rented noncontiguous plots at the same time (Wu et al, 2005; Daniel et al, 2010). Therefore, this study quantified the degree of land fragmentation, examines the impact on arable crop production in Umuahia-North Local Government Area of Abia State, Nigeria.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

- The study was carried out in Umuahia North Local Government Area of Abia State, Nigeria. It has a landmass of 423,290sq km and a total area of 253,979sq km. Geographically, it lies at the latitude 70 291N and longitude 50 321E. It is divided into two ancestral clans viz Ibeku and Ohuhu clans. The Ibeku and Ohuhu clans are split into 12 antonomous communities namely Nkwoegwu, Umuhu, Isingwu, Nkwoachara, Afaranta, Afaraukwu, Emede, Ossah, Ofeme, Ndume, Amaofor and Isieke. The major economic activities in the area include agriculture and trading.

2.2. Sampling Procedure

- Sampling was carried out in the twelve autonomous communities. Systemic sampling with the assistance of Village Extension agents was employed to select the twelve respondents from each community. Data collection involved Key Informant Interviews and the use of structured questionnaire. At the end of the period a total of 125 farmers who followed through in the course of the study were used for data analysis.

2.3. Measurement of Fragmentation

- The Januszewki (JI) index was adopted in measuring land fragmentation. This index is located within the range of 0 to 1. The smaller the JI value, the higher the degree of land fragmentation. The JI value combines information on the number of plots, average plot size and the size distribution of the plots (Jha, et al., 2005). The index is computed as:

| (1) |

2.4. Capturing the Effect of Fragmentation on Productivity

- In choosing among alternative production functions the Cobb-Douglas is an appealing choice here since we are primarily interested in how land fragmentation impacts production in general rather than fragmentation-input interactions. The Cobb-Douglas production is modeled in the equation below.whereY = value of farm output to the value of inputs per hectare β0, …β5, α2partial elasticities;K = capital services cost;FS =farm size (ha);FI = land fragmentation index (Januszewski’s index);DT = duration of tenure in years;LB = labour measured in mandays; andDS = average distance to farmstead in KilometersTo estimate the parameters, the variables must be transformed into logarithmic form in order to estimate a linear regression model. In the linear equation ε is “the error term which captures the effects of all omitted variables assuming zero mean and unit variance” (Thapa, 2007). The estimated partial elasticities (βi’s) can be defined as “the ratio of the percentage change in output to the percentage change in input” (Thapa, 2007). The higher the elasticity of the input is, the higher the impact it has on the output.In addition to the CD production function, the General Linear Model (GLM) was used, since it’s also utilizes regression analysis. The simple linear regression function is the following:whereyi = the value of the response variable;a and b = the intercept and coefficients;xi = the value of the predicted variable; andei= the random error term (Gjosevski, 2005).The observed data were used to estimate the parameters of the regression function, i.e. the impact of the land fragmentation on the farm productivity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Agricultural Production Systems

- In Umuahia- North about 64 percent of the farmers are involved in the crop production. However, arable crop production is dominant and the prevalent farming system is multiple cropping. This is a system that involves growing of more than one crop on the same piece of land. Table 1 presents the socio-economic characteristics of the farmers.An examination of table 1 will show that smallholder agricultural production is practiced in the area. The maximum land area cultivated is 5.2 ha while the minimum is 0.3 ha with an average of 2.68 ha. The maximum age of farmer is 60 while the minimum is 27 with an average of 49 years. The average working distance to the farm is 3 kilometers and this is important when considering the reason for the cultivation of small scattered plots. The average household size is six. Large households results in excessive fragmentation as a result of the need to allocate plots to male descendents in the study area. The mean farming experience is 17 years.

3.2. Extent of Land Fragmentation in Agriculture

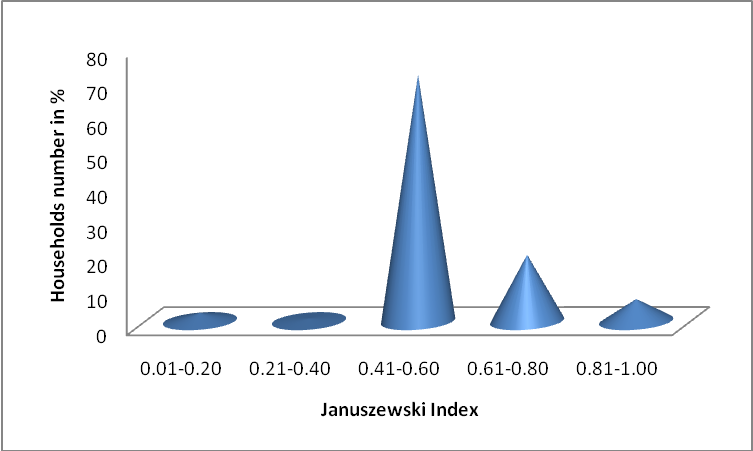

- Individual ownership and communal ownership of land exist in communities. The traditional tenure system of inheritance encourages land fragmentation. The main objective of the study is to investigate land fragmentation in the study area. To realize this objective the Januszewski idex was adopted. The results from the data are presented in table 2.An examination of the table did not reveal a defined pattern. The number of households at the most fragmented farms (0.01-0.20 and 0.21-0.41) and least fragmented farms (0.81-1.00) were low, 2.4 and 6.4 percents respectively. The mean farm size reveals that the households with the most fragmented farms had low acreage cultivated (1.37ha) compared to 2.74 ha at the most consolidated parcels. It can be inferred that high degree of fragmentation is associated with the cultivation of small parcels of land. Of note is the concentration of a high percentage of the respondents at the middle class that cultivated the largest acreage in comparison to other classes 2.78 hectares of land on the average.

|

| Figure 1. Households distribution in relation to Januszewski index |

3.2. Land Fragmentation and Agricultural Productivity

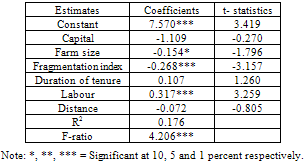

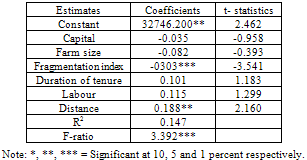

- The Cobb-Douglas production function of the model estimates the effect of land fragmentation and other socioeconomic variables on the output of arable crop production. The results are presented in table 3. In the CD production function farm size and fragmentation index had a negative effect on productivity. Farm size was statistically significant at 10 percent and by implication negatively affected productivity. Land has remained the single most important factor of agricultural production but the result obtained could be explained by the fact that given existing technologies it would be uneconomic to drive productivity through increases in farm size. The existing technology is limited to rudimentary implements, hoe and cutlass which are characterized by high rate of drudgery. As expected fragmentation index negatively affects agricultural productivity and is significant at 10 percent. Excessive fragmentation results in uneconomic sub-division of land. Labour remained the single factor of productivity and is statistically significant at 10 percent. Agriculture in the study area is labour intensive with little or no application of mechanization. An additional man hour employed in agriculture will cause productivity increases by 0.32 percents per hectare cultivated.

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The objective of this study was to determine if the land fragmentation influences the agricultural production. The aim was to examine the degree of land fragmentation represented by the Januswewski index and the attendant effect on arable crop production. In this study, various methods have been used to investigate the impact of land fragmentation over farm productivity, including both the Cobb-Douglas production function and the General Linear Model. Using cross-sectional data from 125 observations, spread across the 12 autonomous communities in Umuahia North Local Government Area of Abia State, Nigeria, it was found that land fragmentation had negative impact on arable crop production. The socio-demographic statistic show average household membership of 6 persons per household. The average number of years spent on education is 7 years and the average farm size cultivated in the study area is 2.68 hectares. The Januswewski index of fragmentation shows the minimum index to be 0.01 with a maximum of 0.98. The average level of fragmentation in the study area is 0.55 which is relatively high considering that agriculture is an industry of major proportion. The estimates from the Cobb-Douglas model revealed that land fragmentation had a negative and significant impact on the crop production. The Generalized Linear Model confirmed the negative and statistically significant influence of land fragmentation. The CD production further re-affirmed the importance of labour in increasing agricultural productivity. Agriculture is highly labour intensive as there is little application of mechanization. The introduction of average distance of farm to homestead was statistically significant, implying that the further the distance away from farms, the likelihood of getting higher output. Farm size was not statistically significant in both models. The explanatory powers of the estimated equations were low, although the f-ratios were highly significant. The study concludes that excessive fragmentation will adversely affect productivity more also when there is low application of modern inputs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I remain indebted to the management of the Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike led by Prof. Hilary Odo Edeoga for granting me permission to take up Post Doctoral fellowship. I remain most thankful to the authorities of the Universiti Sains Malaysia for the excellent facilities provided during this fellowship. To the most HIGH, YOUR GRACE IS EVER SUFFICIENT.

References

| [1] | Daniel, M., K. Deininger, and H. Nagarajan, “Does land fragmentation reduce efficiency: Evidence from India”. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association 2010 AAEA, CAES, & WAEA Joint Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado, July 25-27, 2010 |

| [2] | Hristov, J. “Assessment of the impact of high fragmented land upon the productivity and profitability of the farms -The case of the Macedonian vegetable growers”. SLU, Department of Economics Thesis 561 Degree Thesis in Business Administration Uppsala, 2009 |

| [3] | Najafi, M. R. “Watershed Modeling of Rainfall Excess transformation into Run-off”. Journal of Hydrology, 270:273-281, 2003 |

| [4] | J. Thomas, “Property rights, land fragmentation and the emerging structure of agriculture in Central and Eastern European countries”. Electronic Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics. Vol. 3, No. 2, 225–275, 2007 |

| [5] | S. Thapa, 2007, The relationship between farm size and productivity: empirical evidence from the Nepalese mid-hills. CIFREM, Faculty of Economics, University of Trento |

| [6] | S. N. Tan, G. Heerink, Kruseman and F. Qu 2008, Do fragmented landholdings have higher production costs? Evidence from rice farmers in Northeastern Jiangxi province, P.R. China. China Economic Review 19, 347–358 |

| [7] | R. Sabates-Wheeler, “Consolidation initiatives after Land Reform: responses to multiple dimensions of Land Fragmentation in European Agriculture”. Journal of International Development, 14, 1055-1018, 2002 |

| [8] | P. Sundqvist and L. Andersson, L. 2006, A study of the impacts of land fragmentation on agricultural productivity in Northern Vietnam. Bachelor Thesis, Department of Economics. Uppsala University. Sweden |

| [9] | Y. L. Fabiyi, 1984, “Land Administration in Nigeria; Case studies of Implementation of land Use Decree (Act) in Ogun Ondo and Oyo State of Nigeria”. Agricultural Administration 17(1): 21-31 |

| [10] | L. M. Olayiwola and O. Adeleye, “Land Reform- Experience from Nigeria”. Paper presented at the 5th FIG Regional Conference on Promoting Land Administration and Good Governance, Accra, Ghana, March, 8-11, 2006 |

| [11] | Z. Wu, M. Liuand J. Davis, 2005, “Land consolidation and productivity in Chinese household crop production,” China Economic Review, Vol. 16: 28−49, 2005 |

| [12] | M. Daniel, K. Deininger and H Nagarajan, Does land fragmentation reduce efficiency: Evidence from India. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association 2010 AAEA, CAES, & WAEA Joint Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado, July 25-27, 2010 |

| [13] | R. Jha, H. Nagarajan and S. Prasanna, 2005, “Land Fragmentation and its Implications for Productivity: Evidence from Southern India,” ASARC Working paper 2005/01, available online:http://rspas.anu.edu.au/papers/asarc/WP2005_01.pdf |

| [14] | D. Gjosevski, 2005, Statistics- workbook. Faculty for Agricultural Sciences and Food, Skopje |

| [15] | M. Keymer, C. Linhart, P. M. Rintelen, M. Stumpf and R. Widermannn, “Der Einfluss der Flurbereingung auf die Bewirtshaftung landwirtschaftlicher Betriebe in Bayern MatFib 16, 1989 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML