-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2024; 13(1): 5-14

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20241301.02

Received: Jul. 1, 2024; Accepted: Jul. 24, 2024; Published: Aug. 10, 2024

Organisational and HR Incentives for Intrapreneurship: Analysis of the Challenges Facing Small and Medium- Sized Enterprises

Napoleon Arrey Mbayong

Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences (FEMS), University of Bamenda, Bambili, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Napoleon Arrey Mbayong, Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences (FEMS), University of Bamenda, Bambili, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study seeks to identify more precisely the approaches to intrapreneurship implemented within small firms. In particular, we are interested in the internal context specific to these companies, which is likely to encourage intrapreneurship, as well as the measures implemented to stimulate the creative spirit of staff members. We focus mainly on three factors: 1) the organisational choices made by the company's management to create a work environment and autonomy conducive to initiative-taking and the emergence of innovations; 2) the role played by line management in supporting and encouraging intrapreneurs to develop their projects; and 3) the human resources management practices in place to detect, develop and stimulate intrapreneurial skills. We structure our thoughts as follows. We carried out a quantitative study among 42 SMEs (20 small and medium-sized businesses with 3 to 8 employees, and 22 SMEs with 25 to 137 employees) in different sectors marked by a strong need for innovation: architecture, electronics, energy, geo-technology, IT and software, advertising, business services, etc. Data collection was carried out via an electronic questionnaire sent to employees. A total of 311 employees were invited to complete the questionnaire. The employees' responses were cross-referenced with a questionnaire sent to their direct superiors. A total of 64-line managers were asked to complete a questionnaire on their subordinates. The questionnaires were designed using a range of complementary measurement scales. Findings suggest that SME managers wishing to stimulate intrapreneurial behaviour within their company need to pay particular attention to the choices they make in terms of human resources management. The implementation of simple; HR tricks designed to promote intrapreneurship is far from sufficient, and may even prove counterproductive in some cases. On the contrary, we need to think about and implement an HRM policy with an individualizing essence, conceived and articulated around the intrapreneurial objectives pursued. Before being generalized, however, these conclusions call for further empirical research, aimed in particular at gaining a better understanding of the possible interactions between the development of intrapreneurship, employee participation in the realization of innovative projects and employee loyalty to their company. We see these studies as a relevant complement to our own reflections and, more generally, to ongoing work on the stakes, ins and outs of intrapreneurship.

Keywords: Organisational and HR incentives, Intrapreneurship, Challenges facing small and medium- sized enterprises

Cite this paper: Napoleon Arrey Mbayong, Organisational and HR Incentives for Intrapreneurship: Analysis of the Challenges Facing Small and Medium- Sized Enterprises, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2024, pp. 5-14. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20241301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- While intrapreneurship is recognised as a powerful vector of strategic innovation for companies able to seize it, the factors likely to stimulate intrapreneurial behaviour on the part of staff members remain relatively unknown at present, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises. It is with this in mind that we are writing. Based on the results of an empirical study carried out in 12 SMEs, our contribution examines the influence of three a priori fundamental factors in the development of intrapreneurship: the organizational choices made by the company's management, the role played by line management and the human resources management practices in place.Defined in its broadest sense as "taking part in a company" (Pinchot, 1985) or as "the implementation of an innovation by an employee, a group of employees or any individual working under the control of the company" (Carrier, 1996), intrapreneurship today appears to be a powerful vector of strategic innovation for companies capable of seizing it. This new approach to organizational innovation, mobilizing the ideas, skills and creative capacities of staff members, is supposed to help companies enter into more pronounced innovation logics, an imperative made necessary not least by the many pressures companies now face.Initially and mainly studied in large groups - characterised in particular by the presence of powerful R&D and marketing departments in charge of innovation policies - intrapreneurship is nonetheless a relevant approach and a source of added value for all types of organization. Carrier (1991, 1994, 1996), Zahra et al. (2000) and Messeghem (2003) argue explicitly that small and medium-sized enterprises should also include intrapreneurs and call on the innovative ideas of their employees to ensure their strategic development, taking the opposite view to some authors who believe that intrapreneurship is above all the prerogative of large firms (Champagne and Carrier, 2004). Nevertheless, the development of intrapreneurship in the SME context remains a little-explored field of research at present (Carrier, 2002; Basso and Legrain, 2004). As a result, there seems to be little empirical research on the way in which small-scale structures mobilize intrapreneurship in their activities, on the measures that SMEs concretely implement to stimulate initiative-taking by their staff, and on the effects, this has in terms of workers' effective involvement in the life of their company and in the development of potential innovations.This is the background to our contribution. Based on an in-depth quantitative data-gathering process involving directors, managers and employees from twelve SMEs operating in different business sectors, we seek to identify more precisely the approaches to intrapreneurship implemented within small firms. In particular, we are interested in the internal context specific to these companies, which is likely to encourage intrapreneurship, as well as the measures implemented to stimulate the creative spirit of staff members. We focus mainly on three factors: 1) the organisational choices made by the company's management to create a work environment and autonomy conducive to initiative-taking and the emergence of innovations; 2) the role played by line management in supporting and encouraging intrapreneurs to develop their projects; and 3) the human resources management practices in place to detect, develop and stimulate intrapreneurial skills. We structure our thoughts as follows. After a reminder of the main issues of intrapreneurship, we question the role played by different contextual elements and organisational devices in the willingness of staff members to intrapreneurship. These remarks lead us to formulate the research hypotheses that form the basis of our empirical study. We then present and discuss the main results - including several a priori counter-intuitive findings - before drawing the main conclusions that emerge from our study.I - INTRAPRENEURSHIP, A POLYSEMOUS CONCEPTWithout going into all the conceptual nuances associated with the polysemic nature of the notion of intrapreneurship (Antoncic and Hisrich, 2003; Basso, 2004; Carrier, 2008; Ireland et al., 2009) and the different terms used in the literature to characterise this form of employee entrepreneurship, it is worth recalling the main issues involved in implementing an intrapreneurial approach within organizations. In fact, there is a clear consensus on this subject in the specialised literature: intrapreneurship involves calling on innovative ideas and mobilizing the creative abilities of staff members, with the threefold - and highly interrelated - aim of strategic innovation, business development and strengthening competitive edge (Pinchot, 1985; Basso and Legrain, 2004; Covin and Miles, 2007; Bouchard, 2009). In other words, the entrepreneurial skills of employees - and even more so those with a real creative spirit and an innate sense of innovation - are solicited and put to use by organisations to help them achieve their objectives, develop new business or optimize their internal operating methods.While such conceptions and motivations for intrapreneurship are widely shared in the literature, the actual forms it is likely to take are more open to debate. Carrier's initial work (1991, 1994, 1996) points to the lack of precision of the concept and its boundaries. Allali (2005), Carrier (2008), Bouchard (2009), Basso et al. (2009) and Ireland et al. (2009) all recognise the diversity of approaches and forms of concretisation behind the notion of intrapreneurship and its general philosophy. In our view, the heterogeneity of "types of intrapreneurship" can easily be summed up around two complementary dichotomous distinctions, which are recurrent in debates on what exactly the concept of intrapreneurship encompasses and in the resulting attempts at classification. The first discusses the opposition between individual and collective intrapreneurship. The second deals with the spontaneous, emergent side of intrapreneurship versus its more organised, management-driven nature. Thus, an initial conception of intrapreneurship sees it as essentially the personal initiative of employees who detect opportunities for innovation, demonstrate pro-activity in this area, bear a certain amount of risk in trying to bring their ideas to fruition and, on this basis, develop (in)innovative projects for the benefit of the organization that employs them. This vision of the particularly creative "lone inventor" (Burgelman, 1983) is, however, criticised by some authors (Amabile and Khaire, 2008), who see intrapreneurship more from a collective, multidisciplinary perspective, based on the exchange of knowledge and the sharing of experience between players with complementary profiles. In this view, the intrapreneur is seen above all as a "team player".The first distinction is between a "project leader" and a "relational entrepreneur" (Brechet et al., 2009), whose role is essentially to bring together different professions, reconcile skills, combine expertise and build a real dynamic of collaboration between players around the innovation projects he pilots on behalf of his employer. The second distinction questions the spontaneous or organised nature of intrapreneurship (Bouchard, 2009). Where proponents of the spontaneous view assume that the concept of intrapreneurship primarily reflects employee-driven innovation initiatives, initiated autonomously and managed in a bottom-up dynamic (Brugelman, 1983), others consider that intrapreneurship can also be the result of a deliberate strategy, desired and driven by management (Kuratko et al., 1993). In this view, the organisation seeks to induce intrapreneurial behaviour among its employees, by creating conditions conducive to the emergence - of ideas - of innovations on the part of staff members and/or by putting in place concrete mechanisms designed to encourage and support intrapreneurial activities (Bouchard et al., 2010). This distinction highlights the paradox surrounding the notion of intrapreneurship, which combines autonomy and freedom, as well as structuring and organization (Thornberry, 2001; Birkinshaw, 2003). This conceptual antagonism can also be clearly seen in practice, depending on whether organisations allow intrapreneurs a greater or lesser degree of freedom of action or, on the contrary, provide a framework for their initiatives through incentives and structural choices designed to guide their creative dynamics (Basso, 2006; Covin and Miles, 2007; Bouchard, 2009).II - INTERNAL FACTORS STIMULATING INTRAPRENEURSHIPIt is from this latter antagonist perspective that the rest of our discussions falls. Without attempting here to detail all of the incentive factors for intrapreneurship, we question the elements that can create an environment conducive to the emergence of intrapreneurial behaviour among staff members, focusing mainly on internal organisational variables, the fruit of structural choices and managerial decisions.In this respect, fostering an "innovation- oriented culture" (Kuratko et al., 1993) is undoubtedly one of the key factors in the development of intrapreneurship. The dissemination of values, aimed at empowering employees and encouraging them to share their ideas and suggest solutions to the problems they encounter, is recognised as a fundamental element in stimulating the intrapreneurial spirit of staff members. While recognising its importance, several authors (Martins and Terblanche, 2003; McLean, 2005) nevertheless stress the need to go beyond this single cultural determinant, which is essentially intangible and fundamentally subjective, arguing that it is the whole of "organizational design" - in the sense of Allali (2005) - that plays a key role in encouraging employees to innovate. In particular, three factors appear to be crucial in this respect: an organizational style or work environment designed to enable intrapreneurs to express their ideas, with a hierarchical structure that supports the intrapreneurial potential of staff and human resources management practices that are also developed with this in mind.1. An organic way of organising workIf there's one term that comes up time and time again when discussing the types of work organisation best suited to fostering intrapreneurship, it's the notions of organisational flexibility and agility, as well as staff autonomy and empowerment. Ireland et al (2006, 2009) highlight the extent to which an "organic" type of structure (Burns and Stalker, 1961) is undoubtedly the most suitable structural- organisational form for the emergence of intrapreneurial behaviour. In total opposition to mechanistic logic (Mintzberg, 1982), with its strict rules and procedures, the organic structure is characterized by, among other things, a low degree of formalization, a largely decentralized decision-making process, a scope based on expertise rather than hierarchical position, a certain flexibility of processes and a free flow of information (Ireland et al., 2009). Decentralised work organisation and the few rules to be respected on a daily basis make this "informal" environment a favourable context for taking initiatives: the autonomy enjoyed by staff members encourages the emergence of ideas and experimentation with innovative solutions, which can then be translated into concrete innovations.This is also in line with Allali (2005), who believes that organizations with an organic design are more inclined to innovate than those with a more mechanistic design. This supple, flexible form of organization, and the degree of actor autonomy that prevails within it, enables intrapreneurial personalities to "unleash their creativity" and "make a difference" through their enterprising behaviour and innovative ideas. Bouchard et al. (2010, p. 12) confirm this trend, arguing that "the intrapreneur's autonomy is his or her most powerful means of action" and as such constitutes a critical dimension of any intrapreneurial ambition.The realization of innovation projects requires the ability to distance oneself from a certain formalisation that might prevail in terms of work organization. Strict rules and rigorous procedures are recognized as counter-productive to innovation: they leave little room for creativity, and tend to distract employees from taking the initiative. In this respect, Hayton (2005) stresses the importance of avoiding unnecessary constraints on staff members if we are to encourage the development of intrapreneurship. The same applies to the role of hierarchical management in this respect: an interventionist approach and control can also prove counter- productive, as employees may perceive this "relative autonomy" - or lack of it - as a lack of trust on the part of their management, and a hindrance to the expression of their innovative ideas.Hypothesis 1. Staff autonomy, characteristic of an organic way of working, encourages intrapreneurship.2. Appropriate support from line managementWhile the literature suggests that overly controlling hierarchical management generally tends to inhibit staff initiatives, it also suggests a number of ways in which quality leadership can be exercised to motivate and encourage employees' intrapreneurial spirit. Birkinshaw (2003) stresses the importance of management style and hierarchical support in the development of innovative projects. Ireland et al (2009) emphasize the crucial role of top management and line managers in disseminating a pro-intrapreneurial spirit and encouraging staff to be innovative. More than just spreading a culture of innovation, line managers are called upon to actively support the development of intrapreneurship.This dual role of support and backing involves encouraging employees to share their ideas, to innovate and to "think outside the box" when necessary, as well as providing them with the resources they need to do so necessary - financial, technical, human, etc. - (Ireland et al., 2009). Encouraging intrapreneurship also means delegating a certain amount of decision-making power to the bearers of innovative projects, "networking" good ideas and stimulating collaboration."This support for employees in their innovation process also relies on the establishment of a relationship of trust with line management. This support for employees in their innovation process also relies on the establishment of a relationship of trust with line management (De Zanet, 2010), especially in SMEs where interdependence between individuals seems stronger.The autonomy and freedom of action given to employees who invest in innovation projects must be balanced, however, by a greater sense of responsibility and the acceptance of a monitoring role for the developments undertaken. While line managers play a "sponsoring" role in intrapreneurial initiatives, by supporting and delegating resources to the initiators of innovative projects, they also play a dual role in evaluating and selecting the innovative ideas of staff members (Ren and Guo, 2011). It's up to middle management to assess the feasibility of proposed projects, identify their strategic potential and assess their potential contribution to the company's development. This assessment should then lead managers to prioritize projects, invest the necessary resources in them, and provide the necessary support to ensure their effective implementation. This process of identifying opportunities and selecting "high-potential projects" is a key factor in the company's success and confers an important role on line management, not only in supporting and stimulating creative staff members, but also in ensuring the proper use of resources and the strategic coherence of the innovations undertaken.Hypothesis 2. Appropriate support from line management - geared towards encouraging and empowering staff members and supporting projects with potential - encourages intrapreneurship.3. Individualizing and stimulating human resources management policiesFinally, in addition to the anticipated influences of work organization and hierarchical supervision, human resources management policies also seem to play a key role in stimulating employees to take the initiative. The development of intrapreneurial initiatives appears to be widely encouraged in environments with HRM systems that encourage and recognize initiative-taking. This trend is highlighted by Ireland et al (2006), who emphasize the importance of innovation- and creativity-oriented organizational design being accompanied by innovation- and creativity-oriented HRM practices, particularly in terms of recruitment, training and skills development, management by objectives, appraisal, team-building, coaching, rewards and recognition.Organizations wishing to see intrapreneurial-type initiatives develop within their ranks are therefore well advised to integrate this aspiration into their recruitment/selection process: alongside the skills required by the actual content of the job, criteria such as creativity, self- reliance, self-confidence, initiative- taking, flexibility, risk-aversion and project management are additional dimensions on the basis of which "desired profiles" will be sought out and hired (Morris and Jones, 1993). These "intrapreneurial attitudes" can also be worked on through dedicated training courses, focusing in particular on empowerment, the detection of innovation opportunities, risk-taking or ways of finding resources - internal or external - for the development of innovative ideas. In this respect, Morris and Jones (1993) highlight the fact that individual-centred training, focused on the acquisition of new skills and oriented towards career development, is a practice likely to stimulate intrapreneurship.The question of rewarding staff for their commitment to innovative projects is more controversial. While they are a mark of recognition by the organization of people who are fully committed to their work and to the structure that employs them, as well as an explicit signal of the opportunity to pursue an intrapreneurial project (Bouchard, 2009), the nature that these "incentives" should ideally take on appears more controversial. Two options coexist in literature: financial rewards and formal, non-financial, more symbolic forms of recognition, such as awards, trophies or media coverage of successful initiatives (Pinchot, 1985; Ireland et al., 2006). While some consider financial rewards to be a motivating factor for intrapreneurs, others believe that the most important thing for them is to express their potential and "realize their potential", while being recognized for their actions if need be. While the debate is not settled, a consensus is emerging on the importance of recognition, whether financial or non- financial: these rewards - which should ideally concern both the individual and the group, with the aim of encouraging cooperative behaviour - are necessary to compensate for the risk-taking and persistence required to bring an innovative project to fruition (Bouchard, 2009). Marvel et al. (2007) also emphasises this importance: rewards give individuals the impression that they are valued. This enables them to "stand out from the crowd" and to carry out projects that would not necessarily have been possible without them. Recent developments in literature on the subject suggest making the success of intrapreneurial initiatives a key element of staff appraisal policy, with a view to recognizing the merits and skills of employees, as well as formally highlighting the performances that have been achieved.These considerations are reminiscent of the individualizing model proposed by Pichault and Nizet (2000). This model focuses on the notion of competencies, which become the central focus of HRM practices, particularly in terms of recruitment and selection, appraisal, promotion, remuneration and training. Based on the principle that employees are masters of their own personal development and career path, this model gives pride of place to management-by-objectives techniques: empowered and competent, employees are given a certain amount of freedom to carry out their tasks and achieve their objectives. "This is achieved through evaluation, promotion and remuneration policies that recognize their merits and reward those who invest themselves in their work and in the development of the business. If such practices are seen as a driving force behind the development of intrapreneurship, they are even more so if the criteria underpinning the policies in place make explicit reference to the intrapreneurial skills of staff members and the investment they make in generating innovative ideas and participating in the development of new products/services. As implied in our previous comments, focusing HRM practices on the skills and behaviours expected of "intrapreneurial profiles" should help stimulate employee initiative. In other words, it seems to us that while a policy of individualizing HRM may have a positive impact on the company's performance, it may also have a negative impact on the company's performance. Positive effect on stimulating intrapreneurial behaviours and its impact will only be effective if the practices put in place are imprinted and integrate the prerequisites of intrapreneurship. Hypothesis 3. Individualized human resources management practices geared towards taking initiative and stimulating innovation - particularly in terms of skills, training, empowerment and recognition of merit - encourage intrapreneurship.

2. Research Methodology

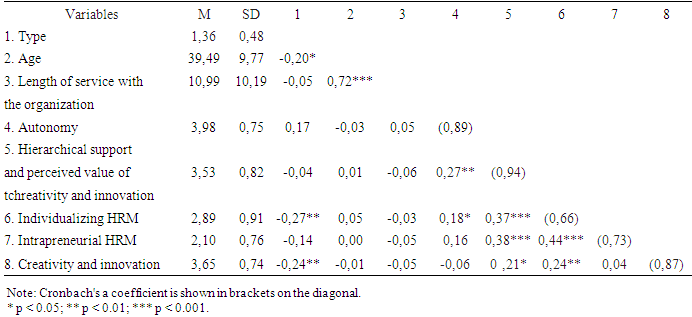

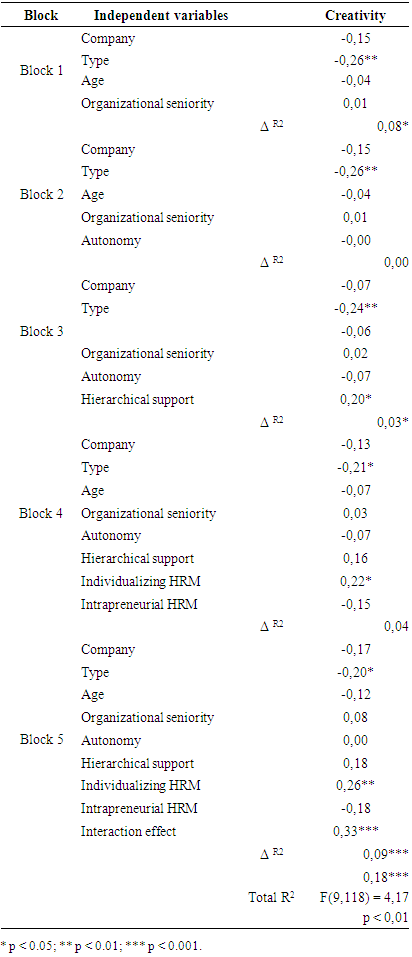

- Research Design and participantsWe carried out a quantitative study among 42 SMEs based in Cameroon, particularly the north west and west regions of the country – 20 small and medium-sized businesses with 3 to 8 employees, and 22 SMEs with 25 to 137 employees; in different sectors marked by a strong need for innovation: architecture, electronics, energy, geo-technology, IT and software, advertising, business services, etc. The targeted purposeful sampling technique was employed in this study in selection of companies listed above and a voluntary selection method was used to choose the employees who participated in the study where top management sent out the questionnaire through emails and anyone willing to participate in the study responded to the questionnaire and participated in the study. The responses of participants where only access by the researcher throw google doc research tools there by protecting their welfare, rights and privacy. As such, there was no reason to subject the study through Institutional Review Board (IRB) as all ethical considerations were observed in the study. Data collection Data collection was carried out via an electronic questionnaire sent to employees. The participants were solicited to answer the questionnaires on the premise of anonymity. The questionnaire was designed in two main parts where part one focused on the demographic characteristics of the respondents such as age of the respondents, gender of the respondents, as well as years spend at the organisation. Part two of the questionnaire focused on the research variables. A total of 311 employees were invited to complete the questionnaire. The employees' responses were cross-referenced with a questionnaire sent to their direct superiors. A total of 64-line managers were asked to complete a questionnaire on their subordinates. Even if the data can be characterized as declarative, collecting the data relating to our research hypotheses from the sources reduces the common method bias. In the end, after matching employee and supervisor responses, we obtained 128 valid subordinate-supervisor pairs, representing a response rate of 41.2%. Men and women accounted for 64.1% and 35.9% respectively of the respondents in our final sample. On average, respondents were 39.5 years old (standard deviation 9.8 years) and have been with their company for 11 years (standard deviation 10.2 years). The majority (85.2%) work full-time for their company. 96.9% have a permanent contract. Finally, 76.6% have a higher education diploma (university or non- university) and 21.1% a secondary education diploma.Measurement scales. The questionnaires were designed using a range of complementary measurement scales. As intrapreneurship has so far been little studied quantitatively, we used various indices relating to the creativity of staff members, their involvement in innovative projects, the emergence of innovative ideas within the companies studied and the implementation of innovations by employees, in line with the theoretical definitions of the concept of intrapreneurship and its potential stimulants already mentioned. In particular, the organic way of working was captured via employees' perceived autonomy in their tasks. To this end, we used the 3 items of the "self-determination" dimension of Spreitzer's (1995) psychological empowerment scale, self-determination being seen here as an individual's perception of having the choice to initiate and regulate actions in the professional setting. Hierarchy's perceived appreciation of creativity and innovation was measured via 6 items proposed by Farmer et al. (2003). These indicators capture the extent to which employees consider that management values creativity and, as a result, encourages them to undertake innovative projects. The individualizing and intrapreneurial characteristics of HRM practices were each measured via 3 items created from the classifications and characterizations given by Pichault and Nizet (2000). Finally, employees' creativity and innovation were measured in relation to their hierarchical superiors via the 5 items proposed by Alge et al. (2006). For all these variables, respondents were asked to position themselves in relation to each of these statements, using an agreement scale of the following type; 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability of our questionnaire and measurement model was verified by confirmatory factor analysis, as per standard practice in quantitative research (see Table 1).

|

|

3. Discussions; How to Stimulate Intrapreneurship in Smes?

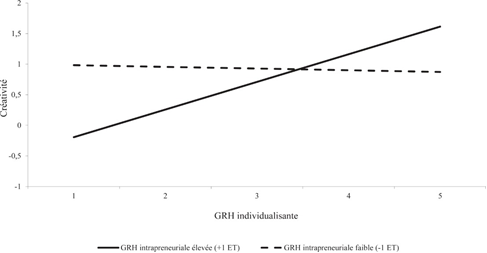

- These results provide a clearer picture of the factors stimulating intrapreneurship in the SME context. In addition, some of the results are counter-intuitive, nuancing or even invalidating the hypotheses we initially formulated on the basis of specialized literature on the subject.1. Organizational autonomy not a source of intrapreneurship as suchThus, while several recent writings assume that a certain autonomy and freedom of action for employees will make them more intrapreneurial, empirical results do not confirm this trend. They also show that a priori suitable organizational characteristics are far from sufficient to motivate staff creativity and stimulate the development of innovative projects. In other words, just because employees are autonomous doesn't necessarily mean that they will adopt a work ethic geared towards seeking out innovations and finding ways of improving their employer's business.A good number of companies have understood this: they are setting up organizational dis- positives to stimulate the creativity of staff members and invite them to take part in intrapreneurial logics. These include the introduction of innovation competitions, the organization of thematic meeting points on the life of the company and improvements to be made, the setting up of task forces to work on cross-functional projects, and the development of procedures to support intrapreneurs with mentors recognized for their skills in project management and innovation management (Bouchard, 2009; Lisein and Degré, 2011). While these examples come mainly from large groups, we feel they can be transposed relatively easily to the SME context, a fortiori in the most flexible structures where the need for innovation is a major challenge. Similarly, the use of constructive monitoring techniques, focusing in particular on the proper use of organizational resources, on the coherence of the company's strategy, and on the quality of initiatives undertaken, on selecting "high-potential" projects, on encouraging staff members to pursue their ideas, or on networking staff members active in innovative projects with ad hoc resource persons, is an avenue worth exploring for SME managers wishing to stimulate intrapreneurship, while structuring their company's strategic development.Without necessarily conflicting with the need for autonomy that intrapreneurs generally tend to demand in the management of their innovative projects, these formal arrangements make it possible to structure entrepreneurial initiatives, to guide staff members in their innovation initiatives when necessary, and to make available to the most promising projects the resources needed to bring them to fruition. In this respect, Bouchard et al (2010, p. 13) consider that "the introduction of formalized assessment and support procedures sends out a strong signal to potential intrapreneurs", particularly with regard to the willingness of the company's management to encourage intrapreneurial initiatives and to support staff members embarking on this path.

4. Conclusions

- Our empirical study has sought to identify the internal contextual elements and structural arrangements that are likely to stimulate the development of intrapreneurship in small and medium- sized companies. For example, while organizational choices conferring a certain degree of autonomy and freedom of action to staff members in the performance of their daily work are generally considered to be conducive to initiative-taking and the emergence of innovations, our empirical results show that these do not as such have a significant effect on creativity and the implementation of innovations by employees. Autonomy and freedom of action alone are not driving forces behind intrapreneurship. On the contrary, they call for complementary managerial practices and techniques, thought through and implemented through a systemic approach. Among these, the supportive and encouraging role of line management is of undoubted importance in the development of intrapreneurial projects. However, this managerial leadership appears to be less influential than the choices made by managers in terms of human resources management. Indeed, our statistical results underline the predominant influence of HRM practices - particularly in detecting, developing and stimulating the creative skills of staff members - on the development of intrapreneurship within SMEs. In this respect, our study highlights the importance of a well-thought-out "HR strategy", imbued with both an individualizing logic and the prerequisites of intrapreneurship, particularly in terms of skills, involvement and recognition of merit. The integration of these two approaches, translated into action by the incorporation of intrapreneurial criteria into the individualizing practices put in place, appears to be a key and relevant HR policy for stimulating the creativity and involvement of staff members in the development of innovative projects.These findings suggest that SME managers wishing to stimulate intrapreneurial behaviour within their company need to pay particular attention to the choices they make in terms of human resources management. The implementation of "simple" HR tricks designed to promote intrapreneurship is far from sufficient, and may even prove counterproductive in some cases. On the contrary, we need to think about and implement an HRM policy with an individualizing essence, conceived and articulated around the intrapreneurial objectives pursued. Many SME managers will undoubtedly have to make an effort - especially in structures where HR policy is still relatively unstructured - to develop such an "HR strategy with an intrapreneurial vocation", but this is not enough and seems to be an essential prerequisite for truly stimulating intrapreneurial behavior among staff members. The creation of such a "favorable environment" for the generation of innovative initiatives and the growth of intrapreneurship, if developed in a coherent manner and adapted to the strategic and organizational context specific to each structure, also appears likely to offer SME managers an additional advantage: that of staff loyalty. Through the implementation of practices focused on empowering staff members, on their effective involvement in the life of the company and on the recognition of their merits, the development of an "HR strategy with an intrapreneurial vocation" - and, more generally, the encouragement of employees to develop intrapreneurial behaviours - is a key factor for success.This element is certainly not to be underestimated by SME managers. This is certainly not something to be underestimated by SME managers in a job market marked by a strong "war for talent", in which they sometimes find themselves at a disadvantage compared to the "attractive potential" of large groups. Before being generalized, however, these conclusions call for further empirical research, aimed in particular at gaining a better understanding of the possible interactions between the development of intrapreneurship, employee participation in the realization of innovative projects and employee loyalty to their company. We see these studies as a relevant complement to our own reflections and, more generally, to ongoing work on the stakes, ins and outs of intrapreneurship.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML