-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2020; 10(2): 40-44

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20201002.03

Received: Aug. 6, 2020; Accepted: Sep. 2, 2020; Published: Sep. 15, 2020

Factors That Promote Organizational Learning in Human Resources Professionals in Puerto Rico

Edgar Rodriguez Gomez, Cesar Sobrino Rodriguez, Eulalia Marquez, Litza Meléndez Ramos

Business and Entrepreneurship School, Ana G. Mendez University, Gurabo, Puerto Rico

Correspondence to: Edgar Rodriguez Gomez, Business and Entrepreneurship School, Ana G. Mendez University, Gurabo, Puerto Rico.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The research contributes so that organizations can determine how to generate models and processes aimed at the development of organizational learning adaptable to their organizational goals, vision, mission and objectives. The results of this study provide the foundation for organizations to increase strategies of learning and training development towards the transformation of methods, processes, policies, and actions involved in organizational learning.

Keywords: Human Resources, Learning, Organizational Theory

Cite this paper: Edgar Rodriguez Gomez, Cesar Sobrino Rodriguez, Eulalia Marquez, Litza Meléndez Ramos, Factors That Promote Organizational Learning in Human Resources Professionals in Puerto Rico, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 40-44. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20201002.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The need to understand the processes that give way to the development of organizations and to recognize which elements should be examined; such as: knowledge needs, access to emerging technologies and learning processes allow the growth of the organization to be promoted. Failure to access and recognize the loss of positioning of organizations in markets, can limit the development of the organization and promote serious organizational problems that affect its stability. Challenging the relationship of those who learn and how they learn gives way to the transformation of human relations and are skills that explain the continuous change and appropriate adjustment in the environments of lifelong learning (Prieto, 2016). Elements of the organizational effectiveness approach recognizes the need to investigate those factors that influence employee learning so that the organization tends to be efficient and competitive (Toro, 2002).The problem of this research is how is learning acquired in organizations and how do Human Resources professionals in Puerto Rico promote its development? Study variables were identified and evaluated, such as: Learning culture into strategic clarity, training, organizational support, sociodemographic variables, and organizational learning. In addition, learning processes were examined as identified by the scale created and validated by Castañeda (2015). This scale includes 14 items/reagents distributed in three (3) areas; training (4 items), strategic clarity (5 items) and organizational support (5 items). The scale has a Cronbach's alpha value ≥ .70, with adequate internal reliability according to (Kline, 2015). Thus, there is an adequate instrument to be able to investigate organisational learning in human resources.

2. Literature Review

- Learning has been studied by multiple professionals, including industrial-organizational psychologists, from their perspective of developing resources and managing constraints in terms of organizations (Velázquez, 2015). The need to recognize how learning takes place, or what factors influence employees to learn, are fundamental elements in the success of an organization. Learning is defined as the acquisition of lasting behaviour by practice (Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, 2014). However, there are scholars who indicate that the definition of learning can be divided into two types (Salas, 2015):1. Single-loop learning. 2. Double-loop learning.The difference between the two is linked to the responses obtained because of an error. If this response promotes a new action in line with what is expected, then it is considered single-loop learning (Rodríguez & Gairín, 2015). If, on the contrary, modifying the variables in search of new strategies or actions and managing to detect and correct these according to the analyses developed, will give way to double-loop learning, as a response. If the above-mentioned answers are not followed, some of the errors that arise as a consequence of a poorly directed learning process may be created, which may negatively affect human resources professionals in their education and knowledge acquisition process (Díaz, 2016).It is fundamental to promote the acquisition of knowledge; where outlining, establishing and executing are necessary matters to achieve learning, even when people leave the institutions where they work (Rodríguez & Gairín, 2015). Obtaining knowledge promotes progress and the creation of innovation processes, which usually have an impact on new learning techniques for human resources in organizations, being this a fundamental element for the progress of an agency, corporation or organization (Gan & Gaspar, 2012).The generation and permanent use of knowledge in organizations tend to provide that learning processes are developed and improved in them (Rodríguez & Gairín, 2015). One of the most recognized definitions of learning is the permanent behaviour that occurs as a result of the experience that the being has in its relation to the environment in which it is developed (Robbins, 1998).Organizational knowledge is an asset that the company must develop and invest in economic resources to create the necessary conditions (Abella & Zapata, 2011; Castañeda, (2015), propose four conditions for organizational learning to take place: the role of the learning culture, training, strategic clarity and administrative support, a perspective that was adopted in this study. Knowledge about the mission, vision, objectives, and organizational strategy provides the elements of Strategic Clarity needed to strengthen the institution and organizational culture (Castañeda, 2015). In fact, this is supported by what is indicated in the theory of perceived organizational support and in the theory of social exchange where the feeling of support produces an increase in positive attitudes towards the organization and promotes the initiative and participation of the workers, through the felt obligation to give extra effort in exchange for the additional benefits (Jijena-Michel, 2015).Organizational Support TheoryThe need to provide learning support to individuals in companies is framed by what is known as organizational support. It is defined as the availability of physical and technological resources to share knowledge, for example: computers, information and communication technologies, software, and infrastructure (Castañeda 2015). If an organization has the means to combine knowledge resources and these generate new capacities, knowledge sharing is very likely to be effective. Social Exchange TheoryThe culture in the organization is, a transformation of the collective experiences in a system of legitimized temporary rules, product of cultural learnings that, in turn, are induced by the technological and organizational changes produced to respond to the challenges of the market (Enríquez, 2007). Elkjaer (2001), raises that learning in organizations also has a social aspect. The learning process interacts with the organization's culture for its transformation and is enabled in a lasting way through the influence on its values. Rokeach (2010), proposes that: "values are mental representations that are built on the basis of fundamental needs that take into account the demands of society". They serve as a reference point to establish what is desired, provide direction towards what is important to defend and promote the satisfaction of the individual. Schein (1991), on the other hand, postulates that culture is the result of the organization's efforts to adapt to the external environment and at the same time achieve its internal integration.This research considers that the social exchange promotes change, qualifies values, and establishes the continuity of transformation. The literature proposes through authors like Morgan (1998) and Sainsaulie (1990) that the relation between social interchange and the organization must be raised from a structural role of the first one and for this they raised several processes that affect an organization. Among these elements, social adaptation is considered, which includes national culture in a broad sense and what is found there as institutional interdependencies, that is, the effects that cultural interactions with other organizations have on each organization. It includes professional communities, in the sense of the relationships that professionals and workers, both individually and collectively, maintain with their peer group. It also incorporates confrontations; understood as the market's struggles and the positioning they make with the understanding and assimilation of external cultural components. It states that cultural learning consists of the different tacit and explicit ways of representing and disseminating culture within the organization. These influences merge and give rise to the cultural particularities of organizational life. According to Sainsaulie (1990) there is a triple cultural reality: what is transmitted, what is learned and what is inscribed. In fact, all the factors force the individuals in the organizations, according to the technological, organizational and market changes, to learn and apply what they have learned in the production and work processes.Thus, the purpose of this research is the identification and analysis of the factors that promote the conditions for organizational learning and knowledge transmission in the area of human resources in such a way that it is possible to understand how the learning culture, training, organizational support and sociodemographic factors affect the organizational learning of human resources professionals.

3. Methodology

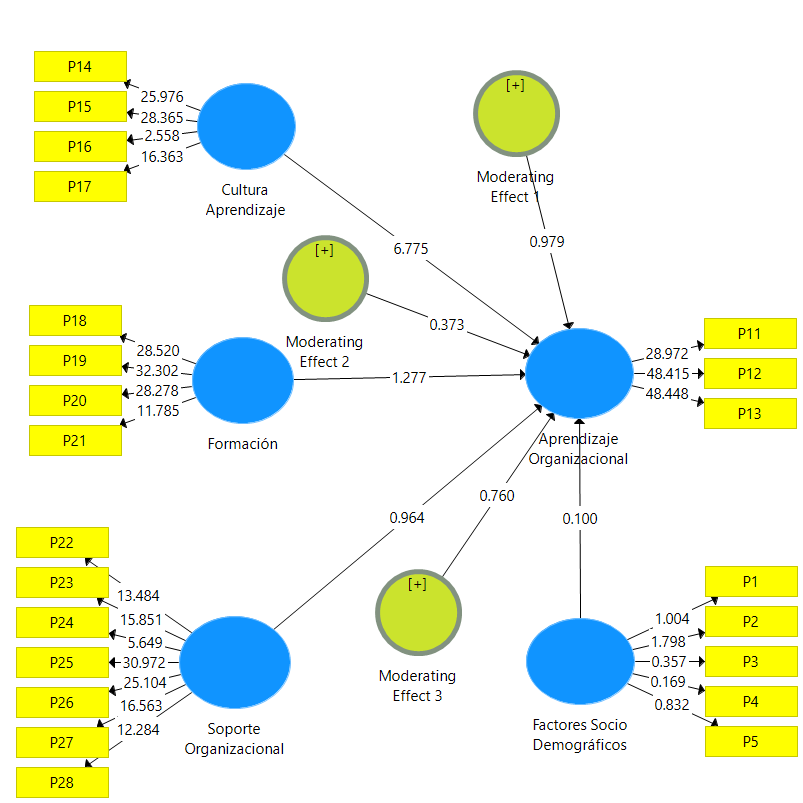

- The research is cross-sectional, observational, descriptive, correlational, focused on identifying the prevalence of exposure and effect in a population sample (Anderson, Sweeney & Williams, 2008). The sample consisted of human resources professionals belonging to the manufacturing (n = 175 of both genders, men = 17% and women = 80% and 3% did not answer), retail, wholesale and service sectors in Puerto Rico. These professionals are members of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), Puerto Rico Chapter. The demographic variables considered were gender, age, industry sector, income level and years of experience in the field of human resources. In addition to the questionnaire to identify the socio-demographic variables, an instrument was included, with permission, which is an adaptation of Castañeda's research (2015) that included 28 premises, answered through a Likert scale from 1 to 5. The Likert scale included the following order: 5 = Strongly agree; 4 = Agree; 3 = Unsure; 2 = Disagree; and 1 = Strongly disagree. His Cronbach's alpha index was .90, which is considered adequate according to Kline (2015). The instrument's premises allowed for the measurement of learning, training, development, strategic clarity, organizational support, and organizational learning.The second stage of the method consists of specifying and recognizing those structural models, and estimating them, recognizing the contribution to the understanding of organizational learning from "Path Coefficients-Bootstrapping". The software SmartPLS was used to carry out this analysis (Chin 2010). It should be remembered that structural models (SM) are a technique that integrates factor analysis with linear regression to demonstrate the degree of adjustment of observed data to a particular hypothesized model and expressed through a path diagram (or Path-diagram). As a result, SM provide those values belonging to each relationship, plus a statistic that expresses the degree to which the observed data fit the proposed model, confirming its validity. Bagozzi, R. & Yi, Y. (2012).

4. Results

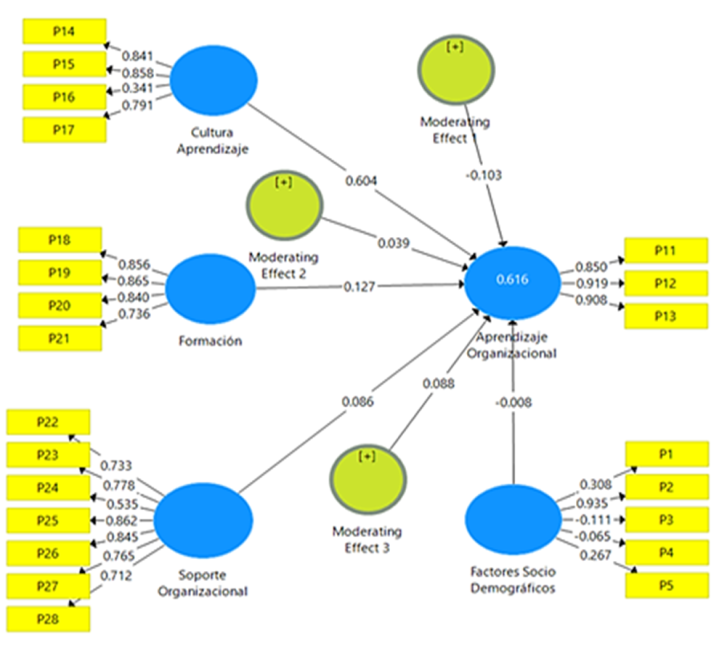

- Based on the modified instrument and its questions, the explanatory contribution is presented below to evaluate the accuracy of estimators with non-parametric methods using the structural equation that best promotes understanding of the inputs of the variables. The Path Coefficients Bootstrap method was used. As reported previously in the sociodemographic data our sample pool has a higher concentration of females. This gender prevalence reflects the general gender distribution that we already have in HR offices in Puerto Rico, where females dominated the HR management areas. It also reflects how females are upgrade in education, as compare to males, in HR's. The objective of making statistical inference is possible with the Bootstrap method, as this re-sampling technique generates "an estimate of the shape, extent and bias of the sample distribution of a specific statistic", Bagozzi, R. & Yi, Y. (2012). Two structural models were identified that contribute to the understanding of organizational learning from the constructs used (i.e., training, strategic clarity, and perceived organizational support).Model A: Structural EquationsThis is a statistical method that relates to the regression of the main components that are in a linear regression by projecting the prediction variables and the observable variables to a new space. The higher the value of R2, the more predictive ability is presented. The model shows the value of 0.616, which is considered substantial. There is a statistically significant relationship between learning culture and training in organizational learning. Chin et al (1998) consider 0.67, 0.33 and 0.10 (substantial, moderate, and weak).

| Figure 1. Model A |

| Figure 2. Model B - Resampling or Bootstrapping |

5. Hypothesis Testing

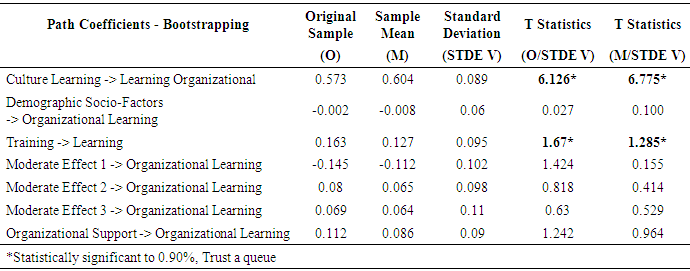

- The following are the answers to the supported and no supported hypothesis tests. See Table 1.

|

6. Conclusions

- Promoting a learning culture requires that information is shared, stored appropriately and made available for transfer according to the needs of the organization and its constituents. Since knowledge transfer is a core activity that facilitates the achievement of organizational objectives since it provides support for the development of innovation processes, it is a concept that must be taken into consideration. Furthermore, it provides for the development of economic and social sustainability. Organizational learning turns out to be a valuable agent characterized by its attributes of inimitable, excellent, and irreplaceable.The research promoted the identification of learning styles based on organizational culture and how socialization, combination, internalization, and externalization strengthen strategic development and contribute to problem solving. On the other hand, training is a variable that must be taken into consideration as a core element in the achievement of organizational objectives and in the development of learning.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML