-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2020; 10(1): 1-12

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20201001.01

How Organizational Justice Makes to Enable Employee Commitment and Voice Behavior in a Team Context: A Mediating Process of Ethical Leadership

Moonjoo Kim

Ewha School of Business, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea

Correspondence to: Moonjoo Kim, Ewha School of Business, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigated the effect of organizational justice as an antecedent of ethical leadership, and tested the effect of ethical leadership on team members’ commitment for team and voice behavior. An empirical study was conducted on 1,057 individuals from 156 teams in 5 Korean companies. As expected, team leaders’ ethical leadership had a positive effect on team members’ commitment for team and voice behavior. In addition, distributive, informational, and interpersonal justice were identified as important antecedents of ethical leadership except for procedural justice. Based on these results, the study offers a profound discussion on practical implications of the effect of team leaders’ ethical leadership and organizational justice for Korean companies and team managers.

Keywords: Ethical leadership, Commitment for team, Korean companies, Organizational justice, Voice behavior

Cite this paper: Moonjoo Kim, How Organizational Justice Makes to Enable Employee Commitment and Voice Behavior in a Team Context: A Mediating Process of Ethical Leadership, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20201001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Recent accounting scandals carried out by various global multinational corporations originated from wrong judgements made by unethical and immoral leaders, and brought about a tremendous economic crisis. The bankruptcy of the gigantic American energy corporation Enron fueled the interest in leaders’ morality and ethicality. This triggered strong criticism on the financial sector, companies, and capital without at least minimum ethics, and the recovery of ethics in CEOs was greatly emphasized. Korean companies are not free from this problem. They stressed the importance of powerful leadership skills in order to reach maximum economic outcomes within a short period of time in the free market economy, and committed the error of judging success of leaders solely based on their economic success.People witness how serious the negative effect of leaders’ ethical failure can be for the organization and the members through the disappointing behaviors of CEOs of corporations. Nonetheless, problems caused by wrong leadership have to be ultimately solved through leadership. Hence, leadership that has a good influence on the members of the organization is necessary more than ever. Many people are concerned about the absence of leadership, and at the same time, the interest in moral leadership and how to determine if someone is a good leader, is on the rise. This is because organizations with leaders that behave ethically and morally demonstrate higher performance. [1] Ethical leadership is a key factor in business ethics. However, its importance was discussed mainly from the normative perspective, and only its effect on ethics-related behavior was largely studied. As a result, empirical studies on Korean companies are not sufficient, and there is a lack of empirical studies on the effectiveness of real organizations.In this context, this study focused on team leaders who stand closest to the position where they can give ethical instructions. [2] Even though new employees have a certain level of ethical values when entering a company, it is noteworthy that it is the immediate supervisor closest to his or her employees who strengthens and maintains these ethical and moral qualities. In particular, the team system, which started expanding for greater organizational performance and efficiency, has been established in numerous companies, and is now the most essential unit that creates organizational performance. More than 80% of Korean companies already introduced and are currently using the team system. [3] The team leader’s leadership and the team are gaining more importance due to changes in human resources management in which evaluation and reward are realized based on team unit.So far, the studies mainly focused on personal characteristics of leaders in regard to antecedents which stimulate ethical leadership. [4] Several scholars argued that personality, moral reasoning, emotion, and moral identity, were the most important factors that determine ethical leadership. [5,6] Even though ethical leadership concept has entailed a variety of leader behavior, it has been failed to clarify accurately what makes this leader ethically. [7] This study took it into account that honesty, trustworthiness, and fairness [8] that ethical leaders demonstrate can be stimulated by an organizational culture in which members of the organization are treated fairly. Therefore, this study selected organizational justice as an important antecedent. This is because organizational justice is one of the important societal characteristics that materialize the cultural value of an organization. [9] Ethical leadership stimulated by organizational justice will eventually have a positive effect on team members’ commitment for the team and voice behavior. The unit “team” is a nested organization embedded in the organization, thus, team members who perceive organizational justice to be high, will have more trust in the team leader who represents the organization and perceive him or her as an ethical leader. Based on the problems discussed above, first it categorized organizational justice as an antecedent that influences the perception of ethical leadership and divided it into distributive justice, procedural justice, informational justice, and interpersonal justice and analyzed the respective effects. Second, the effect of a team leader’s ethical leadership on team members’ commitment for team and voice behavior was analyzed. Third, it was tested whether the perception of ethical leadership functions as a mediator in the relationship between organizational justice and outcomes. Finally, the study suggested several implications found in the ethical practice of ethical leadership and organizational justice for practitioners and mangers of organizations, and offered a proposal for future studies.

2. Organizational Justice and Team Leader's Ethical Leadership

- Ethical leadership is a leadership through which the leader exercises influence on his subordinates based on ethical values and norms, sets an appropriate ethical example, and stimulates his or her subordinates to behave in a corresponding manner. An ethical leader is transactional because he or she suggests clear ethical standards to encourage ethical behavior to the subordinates and uses reward and punishment for conformance. The most frequently cited definition of ethical leadership is “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making”. [10, p. 120] Numerous studies on ethical leadership were later conducted based on this definition. [9] They considered “moral manager” and “moral person” as the two components of ethical leadership. If a moral person is a component focusing on how a leader behaves, a moral manager is a concept that demonstrates the transactional efforts of the leader who strongly communicates the ethical code of conduct expected from the subordinates. In this situation, a moral manager punishes a subordinate who shows a behavior that breaches the suggested standards while stressing the importance of ethics to subordinates, and preemptively giving a positive reward to those who show ethical behavior. [11]A supportive organizational context is required to exercise and maintain this ethical leadership. Considering the fact that organizational justice is an important societal characteristic that can represent the culture and value of the organization, it can be an important antecedent that brings about ethical leadership. This is because organizational justice as a macroscopic factor can influence the perception (a microscopic factor) of team members who are embedded in the organization. [12] Organizational justice refers to a “degree to which an employee perceives the organization he belongs to treats him fairly”. [13] Therefore, it is highly likely that employees perceive ethical leadership based on fairness more positively when they perceive higher organizational justice.Several existing studies have mainly tested the mediating effect of organizational justice, arguing that ethical leadership increases members’ perception of organizational justice and brings about increased performance. [14-16] There are also several others that tested the effectiveness of pure ethical leadership by controlling the effect of organizational justice. [6,17] Nonetheless, considering that organizational justice focuses on the fairness perceived inside the organization, [18] the organizational justice climate can be an important organizational characteristic that stimulates the motivational factors that exist inside the team leader.The concept of justice, which stems from the equity theory by, [19] set its focus solely on distributive justice in its early stage of study because individuals also perceive how fair the rewards and outcomes given to them are. [19] If they believe that the organization provides sufficient rewards corresponding to their efforts and performance, they will trust the team leader, who is the agent of the organization, and perceive his or her ethical leadership as higher. Procedural justice is justice that determines how just and transparent the process and policy for reward allocation is. [13,20] If they perceive the official process for reward allocation within the organization as just and fair, it is likely that they will perceive ethical leadership as higher, which gives importance to the process of the task as well as its result. Further, there is informational justice, which indicates how much correct information is provided to employees in executing the processes of the organization. [21,22] When individuals perceive informational justice as high, which provides detailed and corresponding explanations on the process of reward decisions, it is very likely that they perceive the team leader’s ethical leadership as high, which is embedded in the organization, meaning that the background and information of the allocation are publicized transparently. Furthermore, individuals consider the quality of treatment as very important and are interested in what kind of treatment they receive. Interpersonal justice, which demonstrates the quality of treatment regarding an individual, is the perception of how much consideration and respect the organization and the leader have for their members when they are informed of events related to rewards. [23] Therefore, it can be said that interpersonal justice is high when the members believe that they are treated with respect and are provided explanation on the reward results. This kind of justice is relatively more social and informal compared to the previous explained three kinds of justice. Therefore, it is likely that the team leader is also perceived to be very fair and ethical when employees perceive interpersonal justice as high.According to the social learning theory, employees tend to copy behavior if they see the ethical leader punish unethical behavior, suggest ethical standards, and demonstrate ethical behavior him or herself. [24] This type of positive climate of organizational justice shaped by the top management of the organization, cascades to the team leader, thus he or she also tends to have a high sense of justice and ethicality. In other words, the perception of fairness at an organizational level can exercise a great influence on the perception of the team leader through the cascading effect. This means that the leadership style demonstrated by the team leader can be influenced by the climate and value of the organization. Thus, it can be said that it is ultimately the top management who shapes the organizational culture and climate. [25] Mayer et al. [2] argued that ethical leadership shown by the top management can manifest the trickle-down effect and lead to a team leader’s ethical leadership. The results of this study demonstrate well that organizational justice developed by the top management can be an important antecedent of a team leader’s ethical leadership. When team members perceive organizational justice as high, they will judge the organizational climate and policy as highly ethical. [26] Consequently, the team leader will also tend to treat his or her subordinates in a more fair and ethical manner as an agent of the organization, because fairness is an important behavior of the ethical leader. [27]The team leader can exercise stronger ethical leadership in an organization where organizational justice is rooted in its organizational value and culture. In an empirical study, Rupp and Cropanzano [28] argued that the perception of informational justice and interpersonal justice can have a positive effect on the quality of the relationship with the leader. This is because the perception of organizational justice helps the team leader have an influence as a moral authority. [29,30] Considering the fact that the team leader is a core agent who realizes the value of the organization, [31] his or her behavior conveys information of the organization to its team members. [32,33] Therefore, team members who perceive organizational justice as high can recognize the team leader’s high ethical leadership. Based on this, the following hypotheses were established. Hypothesis 1: Organizational justice is positively related to team leader's ethical leadership.1.1 Distributive justice is positively related to team leader's ethical leadership.1.2 Procedural justice is positively related to team leader's ethical leadership.1.3 Informational justice is positively related to team leader's ethical leadership.1.4 Interpersonal justice is positively related to team leader's ethical leadership.

3. Team Leader's Ethical Leadership and Team Members' Commitment for Team

- Commitment, so far, has been measured mainly based on organizations. There are many empirical studies suggesting that organizational commitment increases performance and productivity, brings positive organizational citizenship behavior, and reduces absence and turnover. However, relatively little has been known about the influence between ethical context and commitment. [34] For this reason, this study argues that a team leader’s ethical leadership can contribute to an increasing commitment for the team, which is a useful indicator for team effectiveness.According to the social learning theory, individuals take a team leader as a role model if he or she shows an ethical and normatively acceptable behavior, and they observe, learn, and copy the behavior. [35,36] A team leader performing ethical leadership is an actor providing ethical guidelines for team members. Consequently, team members copy and learn the behavior of the team leader through modeling, thus he or she had a positive effect on team members’ behavior and attitude. [10.37] In particular, team members tend to show a positive attitude in return for a team leader’s fair treatment and trust in the social exchange relationship between team leader and team members. Various studies, which concluded that ethical leadership has a positive effect on organizational commitment, support this argument. [38-41] The explanation for this is that the perception of the leader treating employees in a fair manner, has a positive effect on their job attitude, and in particular, increases their commitment. [42,43]Employees feel proud of being a member of the team and show a high degree of loyalty when they see a team leader always sharing important ethical standards and emphasizing ethical results in carrying out tasks. Additionally, they show a high level of commitment for the team, which represents the desire to work in the team for a long time with the ethical leader [10] who is fair, trustworthy, honest, and responsible for his or her own behavior. Considering the fact that employees have a strong emotional commitment based on seeing the ethical team leader caring about his or her subordinates and making balanced decisions, the following hypothesis was established. Hypothesis 2: Team leader's ethical leadership is positively related to team members' commitment for team.

4. Team Leader's Ethical Leadership and Team Members' Voice Behavior

- According to the social exchange theory, individuals tend to respond in a reciprocal manner to people who show a respectful behavior toward them. [44] Team members gain trust in the team leader who establishes ethical standards and behaves accordingly, and perceive their relationship with him or her as stronger and as based on social exchange. [10] That is to say, team members think that they have to behave in a way that corresponds with the team leader’s behavior, which reinforces their efforts to pay the team leader back with a relationship that is based on a high level of social exchange. [17] In response to the expectations regarding tasks, the team leader not only makes efforts and suggests solutions to the team’s problems in order to fulfill the responsibilities, but also attracts the attention of team mates. Even if they have an opinion different from that of other team mates, they can show a voice behavior that expresses their thoughts more actively to achieve the team goal successfully. Voice behavior is defined as "promotive behavior that emphasizes expression of constructive challenge intended to improve rather than merely criticize" [45 p. 109]. Voice behavior is not only a behavior that suggests problems and corresponding solutions, but also a behavior that suggests other ideas to achieve goals.Many empirical studies were conducted on the effect of ethical leadership on voice behavior. [4,46,47] As the ethical leader cares about thoughts and emotions of his or her subordinates and pays attention to their opinions, his or her behavior stimulates an active voice behavior. As a result, actively speak up concerning task-related issues as well as ethical issues. [10,46] The ethical leader is a personality that is trustworthy and open to his or her subordinates, thus personal trust is built between team leader and team members. [4,10] Team members trust their team leader more and tend to reciprocally reward him or her with a more constructive voice behavior when they believe that the ethical leader respects and treats them fairly. [4,48] The ethical leader rewards subordinates for their voice behavior and emphasizes its importance, thus provides a supportive environment for voice behavior that allows them to think that voice behavior safe and deeply meaningful. [46,49] The ethical leader publicly points out inappropriate behavior, emphasizes the importance of doing the right thing, encourages voice behavior, and reinforces the learning process through corresponding rewards. [4,46,47] Existing studies argued that ethical leadership stimulates employees' willingness to report problems to the management, [10] and that it has a positive effect on employees’ voice behavior through the mediation of psychological safety. [4] Based on these empirical studies, the following hypothesis was established.Hypothesis 3: Team leader's ethical leadership is positively related to team member's voice behavior.

5. Mediating Effect of Team Leader's Ethical Leadership

- This study also investigated the indirect effect of organizational justice on team members’ commitment for the team and voice behavior through the mediation effect of a team leader’s ethical leadership. High organizational justice does not necessarily directly increase commitment for the team and help actively manifest voice behavior. Team members who perceive organizational justice as high perceive ethical leadership as high as well. Hereby, ethical leadership is based on justice and fairness demonstrated by the team leader, who is influenced by the organization’s fair treatment of its employees. This is because the organizational justice that represents the value and culture of the organization has a trickle-down effect on the ethical leader who, as a result, demonstrates fairness and trust. It is known that fairness may be an important antecedent of ethical leadership, [10] and that ethical leadership has a positive effect on subordinates’ organizational identification. [17,50] Employees believe that the ethical team leader plays the role of the agent who conveys organizational justice, such as regarding policies, procedures, and distribution of the organization. Their trust in the organization allows them to perceive their team leader as an ethical leader. Consequently, they show a high degree of commitment for their own team, and actively perform voice behavior for the team and organization. That is, team members are not only emotionally attached to the team, but also demonstrate solid loyalty. And, if possible, they also demonstrate a high level of commitment for the team because they wish to work in the specific team with the team leader. Furthermore, they will continuously pay attention to issues that affect their team, and demonstrate voice behavior to actively voice their thoughts even if the team mates may be opposed to them. This will also lead to other team mates paying attention to such issues and actively suggesting solutions on behalf of the team. Organizational justice is related to fairness, which is required from the ethical leader. If an organization has strong norms for fairness, this will make team leaders to maintain a fairness identity. [50,51] Further, it can increase team members’ commitment for the team and voice behavior mediated by the team leader’s ethical leadership, which can have a direct effect on team members’ attitudes and behaviors. Based on this, the following hypothesis was established.Hypothesis 4: Organizational justice is indirectly related to team members’ commitment for the team and voice behavior through the mediating influence of ethical leadership.

6. Method

6.1. Participants and Procedure

- This study conducted a survey with employees working in the financial, manufacturing, and service industries of Korea, in order to investigate the effect of team leaders’ ethical leadership and its antecedents. First, a preliminary interview was carried out with the human resources managers of the selected companies. The necessity and importance of this study was explained, and they were informed that the obtained data will be used solely for study purposes and that the research results will be provided afterward. In the final analysis, data from 1,057 individuals were used who are working in 156 different teams of 5 companies, which consisted of a bank from the first financial institution, and saving bank from the nonmonetary institution, semiconductor manufacturer, university hospital, and hotel. Bank employees formed the majority, accounting for 438(41.4%), followed by 294working at a hospital (27.8%), 132 at a savings bank (12.5%), 98 at a semiconductor manufacturer(9.3%), and 95 at a hotel (9%).462 were men, 554 were women, and the majority of them were in their 30s, accounting for 460(49%), followed by 343 in their 20s, 121 in their 40s, and 15 in their 50s or older. In terms of team tenure, 528 or 57% worked less than 2 years. 243 employees for more than 2 to 5 years, and 155 for 5 years or longer in current team. The average team tenure of the total 1,057 surveyed employees was 1.6 years. In order to improve the methodology problem of common method bias, the independent variables (organizational justice) and mediators (ethical leadership) were measured first, and the same team members were surveyed 3 weeks later concerning the outcome variables which are commitment for team and voice behavior. This is because measuring the predictors and outcome variables at a single point in time may possibly cause the artificial covariance effect that is irrelevant to the component factors. [53]

6.2. Measures

- All variables were measured on a7-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree).

6.2.1. Organizational Justice

- Organizational justice was categorized into “distributive justice,” “procedural justice,” “informational justice,” and “interpersonal justice.” They were measured with 3 questions respectively, and 12 questions in total using the questions by Colquitt [13]. The sample items included "My outcome reflects what I have contributed to the organization,” "The procedures used to get to my outcome have been applied consistently,” "Our company has communicated details in a timely manner,” and "I have been treated with dignity".

6.2.2. Ethical Leadership

- Ethical leadership was measured using the Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS) developed and validated by Brown et al.. [10] Sample items include "Our team leader conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner,” "Our team leader can be trusted,” and "Our team leader sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics".

6.2.3. Commitment for Team

- Commitment for the team, which is an important outcome variable in this study, was operationally defined as a “degree to which an individual takes pride in current team and wants to stay in the team for a long time.” The measurement was conducted using the questions with which Allen and Meyer [54] measured organizational commitment, with the subject of the questions changed to “team.”Sample items included "I am proud of being in my team,” "I feel emotionally attached to my team,” and "I want to stay in my team for a long time, if possible".

6.2.4. Voice Behavior

- Voice behavior was operationally defined as a “degree to which employees actively suggest solutions to problems that affect the team and suggest opinions even if opposed to other team mates.”It was measured using 5 questions from the scales by Van Dyne and Le Pine. [45] Sample items included "I speak up and encourage others in my team to get involved in issues that affect my team,” and "I communicate my opinions about work issues to others in my team even if my opinion is different and others in my team disagree with me".

6.2.5. Control Variables

- Finally, the demographic properties of gender and age were controlled to prevent the study results from being distorted or contaminated by external factors. Additionally, the length of tenure in the current team is important in investigating the team leader’s ethical leadership effectiveness because the employee can speak up more easily compared to newcomers. [55] The possibility for varying degrees of commitment for team and voice behavior due to emotional tendency of individuals cannot be ruled out, thus, the positive affectivity and negative affectivity (PANAS) questionnaire was chosen for providing control variables. This is because team members with higher positive affectivity and lower negative affectivity generally show a more positive commitment for team and voice behavior. These traits were measured with 3 respective questions using the survey by Watson, Clark, and Tellegan. [56] The representative question for positive affectivity is “I perform exciting tasks every day,” and that for negative affectivity is “I become irritable with small things from time to time.”

7. Results

7.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Correlation Analysis

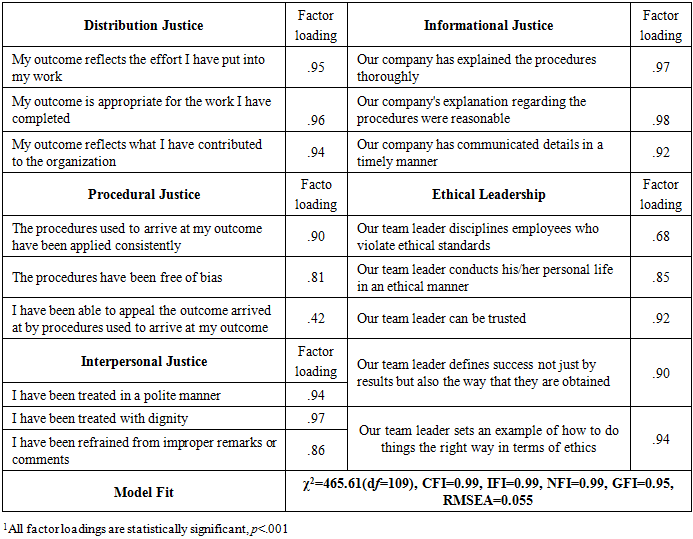

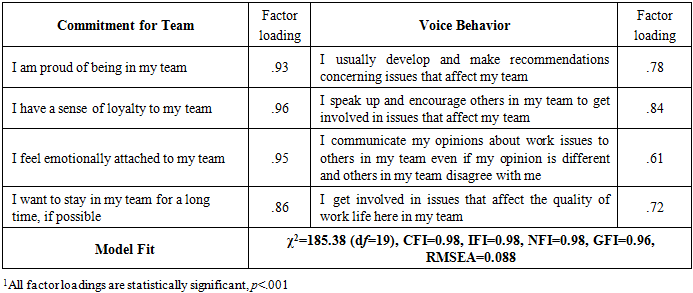

- A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test whether the construct validity of the variables was secured. Ethical leadership surveyed in Time 1 had factor loadings ranging between .68 and .94; distributive justice between .94 and .96; procedural justice between .42 and.90; informational justice between .92 and .98; and interpersonal justice between .86 and .97.Chi square value (χ2) was 465.61; degree of freedom 109; both comparative fit index (CFI) and incremental fit index (IFI) were .99; goodness of fit index (GFI).95; and RMSEA.055. Therefore, the construct validity of the variables was secured. Commitment for team and voice behavior surveyed in Time 2 ranged between .86 and .96, and .61 and .84, respectively. Chi square value (χ2) was 185.38; degree of freedom 19; both comparative fit index (CFI) and incremental fit index (IFI) were .98; goodness of fit index (GFI) .96; and RMSEA .088. Thus, it was concluded that the model’s goodness of fit was good. [57] The details of questionnaire and factor loading are shown in <Table 1> and <Table 2>, respectively.

|

|

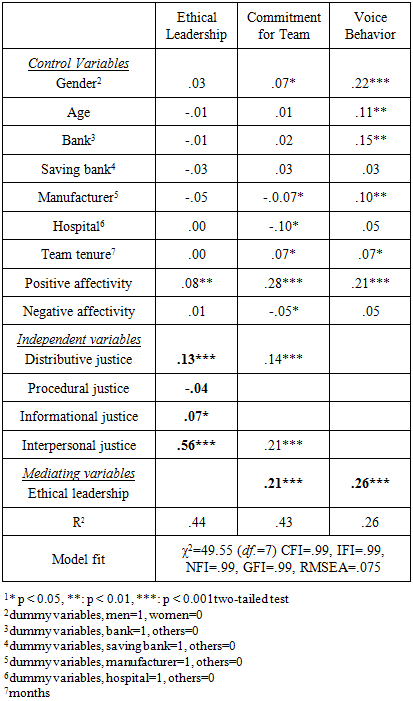

| Table 3. Means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients, and correlations between variables (N = 1057)1 |

7.2. Hypothesis Testing

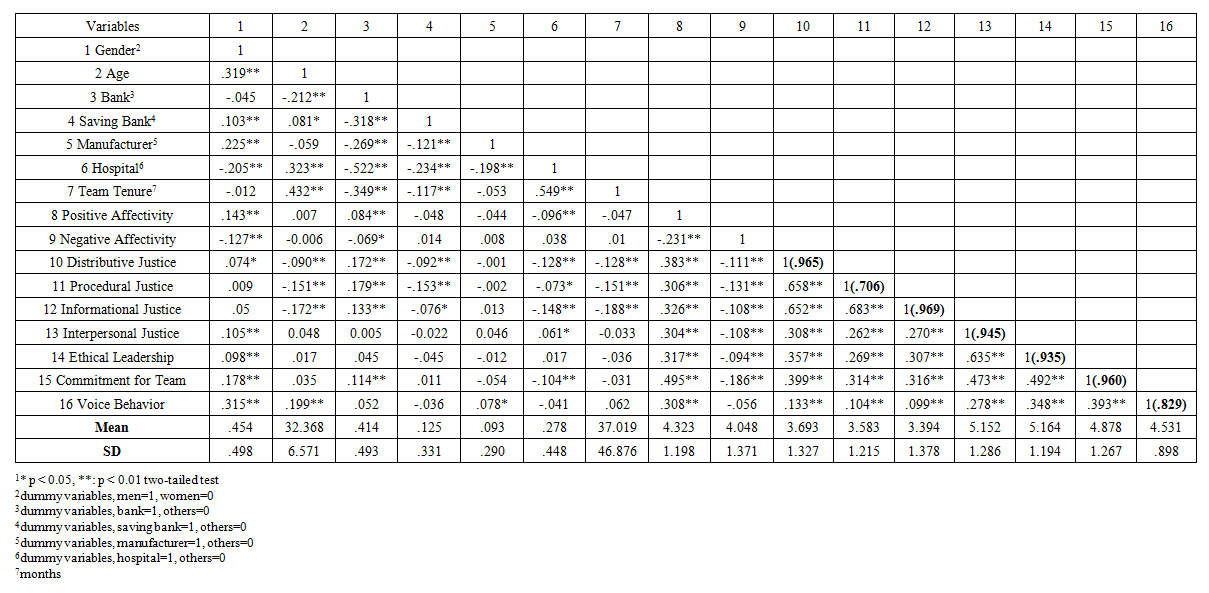

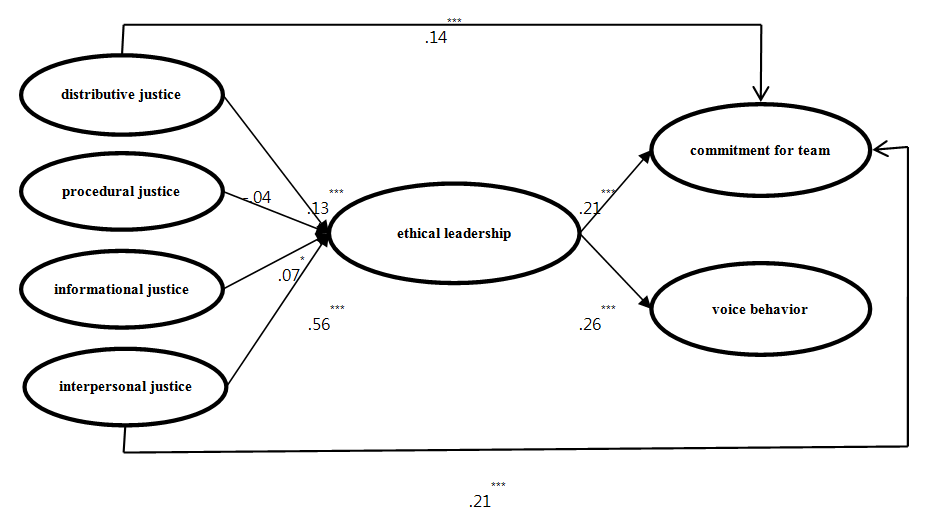

- The hypothesis test was conducted using a structural equation model, and the procedure suggested by Jöreskog and Sörbom[59]was applied. “Distributive justice,” “procedural justice,” “informational justice” and “interpersonal justice” were used as extraneous variables; “ethical leadership” as an endogenous variable and mediator; and “commitment for team” and “voice behavior” as outcome variables. In regard to the correlation between these major variables, distributive justice, informational justice, and interpersonal justice had a statistically significant positive effect on team leaders’ ethical leadership (r=.13, p<.001; r=.07, p<.05; r=.56, p<.001, respectively). Contrarily to the hypothesis, however, the effect of procedural justice on team leaders’ ethical leadership was insignificant (r=-.04), thus hypothesis 1 was partially supported. Further, team leaders’ ethical leadership had a statistically significant positive effect on team members’ commitment for the team and voice behavior (r=.21, p<.001; r=.26, p<.001, respectively), therefore, hypotheses 2 and 3 were all supported. A reanalysis was conducted taking into account the modification index (MI), in which the direct effect of distributive justice and interpersonal justice on commitment for the team was proven (r=.14, p<.001; r=.21, p<.001, respectively). The final analysis results are shown in detail in <Table 4>, and the refined model is shown in <Figure 1>.

|

| Figure 1. Refined Model |

8. Discussion

8.1. Theoretical Implication

- This study empirically investigated the effect of organizational justice as an antecedent of ethical leadership and the effectiveness of ethical leadership, and suggests the following theoretical implications.First, it proved that distributive justice, informational justice, and interpersonal justice are critical antecedents that bring about ethical leadership. Many of the existing studies conducted so far have reported that ethical leadership has a positive effect on organizational justice, but this study is distinguished because it proved that the team leader is the one who puts organizational justice into real practice, and he or she plays the role of a connecting agent who helps team members perceive this organizational justice. Leaders’ personalities, which were frequently investigated as antecedents of ethical leadership, are difficult for organizations to change. On the other hand, employees’ positive perception of organizational justice leads to a positive perception of ethical norms and attitudes of the team leader with whom they perform tasks on a daily basis.Second, the study investigated the positive effect of the team leader’s ethical leadership on team members’ commitment for the team. As the number of companies and organization applying the team system increases, a large commitment for the team can be an important mechanism that ultimately increases organizational performance. Additionally, the fact that the direct effect of distributive justice and interpersonal justice on commitment for the team was proven, suggests that efforts are required at an organizational level to increase commitment for the team.Third, the study verified the positive effect of a team leader’s ethical leadership on team members’ voice behavior, which goes one step further than the existing argument of saying that the ethical leader can prevent subordinates’ unethical and immoral behavior through role modeling. This study suggests that ethical leadership can create an environment where individuals can actively express their opinion about the process of job performance without fear even if team mates are opposed to it. This demonstrates that the ethical team leader can stimulate team members’ creative potential, thus, expanding the range of ethical leadership’s influence.Fourth, the mediation effect of ethical leadership was proven in the relationship between organizational justice and voice behavior. As a result, the study demonstrated that the perception of organizational justice is not sufficient enough to induce voice behavior in employees and trust in the team leader who behaves ethically, treats team members fairly, and shapes a climate where they can actively voice their opinion even if contradictory.Finally, carful explanation is required as the effect of procedural justice on ethical leadership was discarded. Existing studies on organizational justice so far mainly focused on the effect of distributive justice and procedural justice. Relatively less attention was paid to informational justice and interpersonal justice which demonstrate the mutual relationship between the organization and its members. However, it can be said that employees, even though they did not recognize procedural justice, perceived ethical leadership as high once they perceived distributive justice positively and the company informed them of the decision-making allocation process in a polite, transparent, and active manner. This explanation becomes more convincing particularly because the correlations between procedural justice and distributive justice, procedural justice and informational justice, and procedural justice and interpersonal justice, were higher than the relationship between other justice variables. This suggests that it is important that distributive justice and interactive justice (informational justice and interpersonal justice) are secured together.

8.2. Managerial Implications

- The managerial implications for organizations and teams regarding organizational justice and team leader’s ethical leadership are suggested below. First, justice at an organizational level is highly important because a team leader’s ethical leadership is not formed solely through his or her ethical inclination and personality. This is due to the fact that organizational justice shaped by the organization and its top management influences the leadership style of intermediate managers (team leader, for example) through the trickle-down effect, and this ultimately has a positive or negative effect on employees’ attitude and behavior. [2] That is, creating a climate that produces ethical leaders is more important than selecting leaders with ethical inclination. Even if individuals with great ethical inclination become leaders, it will not be easy for them to change employees’ attitude and behavior. The positive effect that their ethical leadership has is not sufficient enough if organizational justice is not guaranteed.Second, it is important to go beyond distributive justice and procedural justice, which were proven to be particularly important among the various kinds of justice, and to strive to enhance informational justice that conveys the decisions on allocation processes in a timely manner by actively communicating with employees. Furthermore, it requires effort to help employees feel respected and treated with dignity in regard to communication with the organization. This is because positive perception of organizational justice has a positive effect on the perception of ethical leadership that is based on the principle of fairness. There is more to ethical leadership than simply punishing team members’ unethical behavior and inducing desirable behavior. It is a leadership that further stimulates team members to actively express their opinion. Therefore, it is essential to create organizational justice, which stimulates ethical leadership, as well maintain ethical leadership through various interventions at an organizational level.Third, the role of the organization is highly crucial, as well as the influence of the team leader who performs tasks with his or her employees every day. Employees who notice distributive justice and interpersonal justice demonstrate a high level of commitment for the team. It is important to reward them fairly for their hard work, but it is also fundamental to treat them with dignity and respectful, which allows them to perceive interpersonal justice on a high level.Fourth, employees’ more active voice behavior is much valued in this current environment where creativity and innovation are crucial and team performance directly translates into organizational performance. Further, voice behavior ispart of a team leader’s ethical leadership. His or her leadership has to stimulate active expression even of contradictory opinions, therefore, it is crucial to strengthen organizational justice.

8.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

- This study contains the following limitations. Efforts to minimize these problems and more advanced investigation is required in future researches.First, this study obtained data from various Korean companies engaged in financial, manufacturing, and service industries, but it is essential to conduct more empirical studies on more diverse industries to achieve generalized study results. Second, this study was designed to survey independent variables and mediators first and to measure the outcome variables based on the same team members after 3 weeks in order to reduce the common method bias problem to a certain degree. In future studies, it is recommended to measure the commitment for the team and voice behavior variables from team leaders or to replace the figures with more objective ones that can directly represent organizational performance.Finally, this study investigated the effect of organizational justice and ethical leadership for task performance on employees working in teams from various industries in Korea. However, it is also important to investigate the effectiveness of ethical leadership as a situational variable. Moral and ethical leader is needed more than ever before. Countless studies were conducted on the positive effect of ethical leadership but no investigation of antecedents that bring about ethical leadership, thus further studies are required on situational variables that can bring about ethical leadership). [5] It is advisable to investigate more diverse antecedents that can further develop and maintain ethical leadership, as well as investigate the mediating effect of ethical leadership for improving organizational and team performance. This would allow to suggest more viable and meaningful solutions to industrial fields and it would certainly contribute greatly to the development of ethical leadership studies.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML