-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2019; 9(2): 33-44

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20190902.02

Conflicts Management through Mediation in Public Administration

Maria Rammata

Phd (University of Sorbonne I), Lecturer Hellenic Open University, Athens, University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece

Correspondence to: Maria Rammata, Phd (University of Sorbonne I), Lecturer Hellenic Open University, Athens, University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper aims to highlight the impact that conflict management has οn the organizational performance and to propose the introduction of the Mediation procedure as an efficient method to respond quickly and informally to conflict situations in the public sector. It first focuses on the potential sources of conflicts that arise, particularly in the framework of the public sector and concludes that services should be administratively capable to overcome those distortions that result in reduced productivity. Then, the paper depicts the deficiencies of the disciplinary regulatory framework in the Greek public administration that: adopts a sanctioning orientation; leads to the instruction of a hostile working environment; is detrimental to the performance of civil servants; fails to reintegrate civil servants in the administration. The research concluded that there is a great need to tackle more systematically the issue of conflicts by introducing the Mediation as a more informal and flexible process that engages a neutral party to assist the disputing parties in their efforts to reach a mutually acceptable settlement. The analysis is backed up by a quantitative research on 500 officials from the Greek central and the local government that concludes that conflict situations that come with the insufficient performance need to be addressed through training and by introducing an institutionalized Mediation mechanism that will manage divergences and will help install a propitious working environment for the general good and benefit.

Keywords: Conflict resolution, Mediation, Organizational performance, Public sector, Directors, Disciplinary framework

Cite this paper: Maria Rammata, Conflicts Management through Mediation in Public Administration, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 33-44. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20190902.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Inter-organizational conflicts may occur either vertically, between groups of different levels of the hierarchy, employees and supervisors, or horizontally, between individuals of the same hierarchical level, such as Managers or employees of the same organization (Blake Mouton, 1964, Schein, 1993). Conflicts and tensions in the workplace involve the formation of competitive relationships where one side creates obstacles to the intentions or goals of the other (Robins, 1974). In reality, conflicts are inevitable as these competing individuals (Longenecher, C. and Neubert, M. 2000), balance opposing forces and seek for an “optimum equilibrium”. In equilibrium, organizations are "open" to manageable disputes (in the sense of openness of the administration and of encouraging the expression of different opinions) and recognize their value (Huczynski A. and Buchanan, D. 2001). In fact, this controlled confrontation between workers or groups (Daft, R. & Marcic, D. 2007), leaves scope for performance, gives energy to individuals or groups to present their approach and to propose ideas to give rise to productivity. If conflicts are considered to be an essential component of any organization, they can still be very harmful to the organizational performance, unless they are regulated at an early stage. In the following chapters we will delve into the subject in order to shed some light on the importance of systematically and effectively dealing with conflict resolution at workplace whether this engages the modeling of a Mediation process that would foster resilience and reconciliation among employees, whether it stresses the need to cultivate Mediation skills for Directors or appointed experts in conflict management and Mediation practice.

1.1. The Sources of Conflicts in Public Organizations

- Chronic disagreements are considered as a serious source of conflicts in the workplace and in most cases, they are relevant to structures, systems, processes, stereotypes, bureaucratic organization and bad relationships, as well as to the ways of rewarding, assessing and valorizing work. Chronic conflicts1 on unresolved issues are recognizable by: The repetition of claims2; the low level of commitment; the tolerance of antagonism (i.e. managing by dividing or through clans, sabotage, etc.); the low level of their resolution; the high intensity of emotions they involve.Other key sources of tensions and conflicts can be found in the way the supervisors perceive and exercise their role. These kinds of tensions have been characterized as “micro-level” conflicts and are mainly related to the perceived psychological contract between the employees and employers (Nye, 1973). What is known as abusive supervising of subordinates (Tepper, 2000, Michel, J.S., Newness, K. & Duniewicz, K., 2016) may take various forms such as:• Verbal or non-verbal violence, favoritism, gossip;• Mobbing: undermining; unfair, subjective and unjustified assignment of duties; expression of irony; discrimination based on gender, religious, political or philosophical beliefs; invasion of privacy; displacement of responsibilities whenever there is a breach from upper to lower hierarchical levels; poor evaluation of the work of the employees (e.g. the Supervisor is extremely strict in one case and elastic to the other), etc.Also, the macro-level sources of conflict (Pondy, 1967)3 can be mentioned such as:• Application of unfair procedures.• Strict evaluation systems that are accompanied by unfair systems of promotion.• Inadequate disciplinary and grievance procedures that impose penalties to civil servants for minor deficiencies or impose minor penalties for very severe deeds, etc.Organizational conflicts lead to the adoption and consolidation of aggressive behavior with unpleasant consequences for the implementation of the service's objectives4. Research conducted by Inness, M., Barling, J., & Turner, N., in 2005 has illustrated that the feelings of "victimization" and "interpersonal injustice" contribute to the adoption of corresponding behaviors of employees - as a retaliation to this situation -, such as : aggression; negativity or inactivation (pathetic reaction); denial of cooperation; disorganization of service; disagreement; negative climate; competition; anxiety; waste of energy; taking long breaks, equipment theft, and/or sabotage, interpersonal deviance5. The economic cost of workplace deviance alone has been estimated to be around $4.2 billion in lost productivity and legal fees (Bensimon, 1994).For the above mentioned reasons, there is an urgent need to propose a serious treatment of this phenomenon as it can be very detrimental to the organization’s performance and the overall economy and society. Conflict’s management and misconducts in Greek public administration or in European administrations merit the involvement of researchers that could propose adequate solutions and facilitate the implementation of current reforms (Pollitt C. and Bouckaert G., 2011).Furthermore, conflicts that appear especially in the public sector merit to be closely researched as they have specific characteristics which will be analyzed below.

1.2. Particularities of Conflicts in the Public Sector and the Recognition of New Qualifications of Managers

- In the public sector, more than in the private, the permanent tenure of employment status creates the condition sine qua non for a stable working environment (Makrydemetres, Pravita, 2012) where appropriate control is exercised and labor disputes cannot be tolerated. In such an environment, tensions can potentiate the atmosphere and act as a catalyst with long-term negative consequences that may end to an organizational paralysis.Some significant sources of conflicts in public service are considered:• The bureaucracy and abundance of legislation that leaves the possibility for subjective approaches.• Lack of standardized procedures for all administrative cases (Makrydemetres Μ., Zervopoulos P. and Pravita M.-E., 2016).• Lack of financial or material resources: supply of consumables, software, equipment, etc. (Pondy, 1967).• Incompetent Directors that are not trained in Human Resources Management (Rammata, 2011) and are “learning by doing”6 (e.g. abusive supervision, Hershcovis, 2011).• Different working conditions and benefits that accompany the various categories of staff that are working on the same project or in the same administration.• Pressures from citizens especially in services with a high rate of users/visitors.• The challenge to transform the vertical and the individualist approach of working with a more horizontal and collaborative way of work, etc.7.• Disciplinary law is very strict and unfair8.Passing from a present, non-desirable situation, that tolerates conflicts and their negative impact, to a better future one, that promotes the settlement of disputes and the cultivation of a warm working environment, would be facilitated by the introduction of a procedure that would promote the disclosure of different options and sabotage traditional stereotypes, such as the management by fear, the authoritarian style of leadership, the prevalence of control, the non-sharing of information, the individualist approach, and so forth. This approach could foster resilience and mindfulness to all parts of the conflict and also, could lead to the development of better individual and team workplace behavior.To face these challenges, Directors must demonstrate skills to manage (Bourantas, D., Agapitou, V. 2014), negotiate, solve, and disseminate the “lessons learned” from managing conflict situations by conducting workplace investigations, coordinating a dialogue with the implicated persons and practicing the mediation process9. As argued by Lewicki, R., Weiss S., & Lewin, D., (1992), “The collaborative behavior is strongly desirable as a way to manage and resolve conflict”, and furthermore Pruitt (1983a) had pointed out that “Integrative agreements are likely to be more stable, to strengthen the parties’ relationship, and to contribute to broader community welfare”…. “an integrative agreement may represent the only possible means of resolution” (in: Lewicki et al.). Apart from the required training on Mediation, a reform in the regulatory basis is necessary, one that would foresee and describe in detail the steps to implement the mediation process, the training needed and the appointed Mediators (from within the Administration or specialized personnel on the field)10.In the following chapter, the Greek disciplinary regulatory framework will be analyzed so as to further explore whether it can be a potential source of tension or whether it settles successfully the disputes that relate to behavioral issues.

2. The Disciplinary Framework and the Discussion on Conflict Resolution in the Greek Public Administration

- Disciplinary Law in Greek public administration aims to seek for the proper and efficient cooperation of the State administrative services by means of the compliance of civil servants with their statutory law, while protecting the well-functioning of the State and its institutions (Spiliotopoulos and Chrysanthakis, 2017). The existing disciplinary procedure is described in Law 3528/2007 (Government Gazette 26, Α΄, 09/02/2007) "Ratification of the Code of State for Public Policies of Administrators and Employees of Public Entities", as amended by the provisions of the more recent laws.It is widely accepted that civil servants must carry out their duties by obeying specific disciplinary provisions that emanate from constitutional values and the current legislative framework. Procedures concerning disciplinary sanctions are stronger and more formalized in public employment than in the private sector, so that to ensure that all personnel adheres to its duty of service to the society and contributes to the prosperity of the economy. This consistency in civil servant’s actions with the fundamental rules and codes of action, strengthens the faith of the society in the performance of the public sector and enhances the respect of people to the values of the public service. Impartiality, objectivity, proportionality, consistency, ethics, personal integrity and lawfulness are considered to guide the administrative conduct of civil servants towards satisfying the public interest. Questions arise as to what should be the recommended methodology that pertains to make respectable these valuable principles, eliminates the cases of violation or misconduct that may lead to a conflict or to the installation of a contradictory culture that is counterproductive.We will state here some of the critics that have been imputed to the application of the disciplinary procedure in the Greek public administration with the corollary that it is extremely rigid, generates administrative burdens that emanate from the excessive use of internal administrative processes that do not necessarily succeed in the resolution of litigations:- Impunity and delays in granting justice: for the majority of the disciplinary cases, decisions take several years to be adopted (Annual reports of the General Inspector of Public Administration) and as a result, in many, even serious cases, the accusations are withdrawn after the expiration of a period of five years (until recently).- The punishments for actions or omissions are not always proportionate to the gravity of the offense.- The regulations are not always clear enough so as to support and help the ability of the administration to demand accountability from its civil servants.- The verdicts of the Disciplinary Assembly are not always enough supported and many of the cases are directed to the Administrative Courts for final resolution.- In many cases, there is no apparent verdict or the personnel, after the period of sentence is passed, they take back their position and may even repeat the same violation.- The verdicts of the Second degree Disciplinary Council that concern the “written warning” or “reprimand” and the fine of “reduction or loss of the salary” until one month cannot be the object of an appeal. So, for many mediums “critical” cases, the disciplinary authority does not respect the constitutional right of civil servants to defend themselves in front of the Assembly and to allow them to submit their own version of the facts.The various amendments of the disciplinary law have attempted to restore the above deficiencies with the objective to increase the level of conformity of civil servants to the rules and regulations of the disciplinary framework. The reformed framework sets forth:• The aggravation of the penalties whenever there is a breach.• The extension of the cases that may enter in the field of the disciplinary procedure by expanding the legal definition of punishable behavior and of all possible misdeeds in a detailed way in legislation.• The shortening of timeframes and the extension of the period of time that the disciplinary sanction could be expunged, i.e., eight years is now necessary for the removal of the penalty of administrative fine instead of five that were up to now (L. 4210/2013).These recent reforms have added more stress in an already hostile given working environment, since the adoption of strict labor measures (among others) of the Memorandum of Understanding with the European institutions: reduction of salaries, reduction or abolition of allowances by also setting a threshold of 3,000 Euros in the remuneration of the public servants and other benefits, premature retirements, abolition of pensions, increase of working hours, etc..Apart from the severe offenses that civil servants may commit (such as fraud, falsification of documents, disclosure of official secret fraud, steel of public assets, etc.11) the following wrongdoings enter as well in the same disciplinary framework and can trigger the convocation the Assembly of the board of inquiry:- The civil servant omits to publish electronically the working of the service on the web site of the administration or the internet or does it, but with mistakes (L. 3861/2010 art. 2 & 4).- The administrative personnel does not make the necessary effort to simplify the administrative procedures and eliminate administrative burdens12.- The civil servant does not reply to the citizens or delays in responding to their demands.- The civil servant breaches the principle of neutrality or of independence and treats subjectively the affairs of citizens.- The civil servant behaves “inappropriately” during service or in his/her private life.- The civil servant omits to collaborate or does not support the working of the Citizen’s Help Center (L. 4093/2012). In this specific case the civil servant is directly put into the suspension of duties before the commencement of the preliminary investigation on the subject (without exercising the right of hearing13).

2.1. Critical approach to the Disciplinary Procedure: Solution towards Mediation

- The foundations of the discipline procedure demonstrate that the procedure is launched without exhausting all sufficient empirical evidence. It would be recommended to : 1) consider informal tools of resolving the behavior, such as discussions with the person in the case, 2) prioritize cases and 3) make sure that there is no misunderstanding in the process. In the above mentioned cases, such as the “delay in answering to the citizens request” or the “delay-denial to cooperate with the “Citizen’s Help Center”, the disciplinary method that is launched automatically is identical to the one applied when civil servants commit: i.e. embezzlement, fraud, falsification of documents, disclosure of official secrets, willful use of Government owned or leased assets, etc.. Thus, the punishment is not proportionate to the breach or the misconduct, and there is not a clear link between punishable behavior and obligations of civil servants. That way, the principle of proportionality14 is violated and whenever there is a suspicion of a breach, civil servants are unable to predict the consequences. This sanctioning orientation of the disciplinary procedure for minor litigations fosters a negative culture, a working environment, that instead of being friendly, becomes hostile, and where, accusations, guilt, fear, resentment and anger are installed among workers or between them and the hierarchy. The current situation that uplifts the minor incident to a serious one, inevitably leads to the polarization of labor relationships between “injured party” (civil servant) and “prosecutor” (Director”) and does not portend a positive resolution or rapprochement of disputing parties in a perspective of smooth reintegration in the workplace.Τhis extremely rigorous procedure is inherited by the traditional top-down approach that creates a gap between the hierarchical levels and does not put forward the interaction, the reconciliation and the possibility to negotiate between layers. Or, modern organizations tend to bypass the top-down level of managing and to put more emphasis on the horizontal interactions internally, as well as with stakeholders, NGOs and other interest groups outside of the organization. And as it is remarked by Peters (Peters, 1998) “As more open conceptions of ‘governance’ (Rhodes, 1997) become the norm, then networked versions of co-ordination involving interest groups, also become more of the norm. This involves substantially more negotiation and mediation than would be true in the more traditional conception”.Also, the regulatory framework in Greek public administration that traditionally emphasizes the need for a detailed structure of laws and regulations to cover all issues, makes it even more difficult to be efficient and flexible and to permit other disciplines than those of legalists to interfere in order to resolve similar matters. Corrective action should be taken in the handling of these minor cases so as to make the procedure more flexible, to give permission to express the divergent opinions, to expose the arguments and support, if there is enough evidence to warrant the initiation of disciplinary action at a second degree. It is wrong to automatically consider all cases as strong legal differences that require a formal disciplinary procedure.This is kind of less stringent and more informal, nevertheless, standard procedure to better handle misconduct or default, is the mediation and the coordinated negotiation between opposing parties. This more “soft” approach would lead to a definitive resolution of the situation at an early stage appearance and would decongest disciplinary procedures that already show signs of inefficiency and time delays in processing the cases. That way, the Second Disciplinary Council would be dedicated to dealing with more important affairs and redirect its essential time and effort of the specialized personnel to promptly and quickly respond, whenever it is called upon. The positive outcomes would be obvious for: the performance of the civil servant, the departmental working environment and the public administration’s culture.The main obstacles to achieve this target and effectively deal with difficult issues, are:- First, to accept the need to determine whether the conduct or circumstance at issue should be initiated as a disciplinary complaint and distinguish offenses from minor to serious ones, from those that require a more strict evaluation and those that could be easily treated in a consensual manner through the mediation.- Second, to eradicate the old stereotype that all issues need a legal formal treatment in order to be resolved.- Third, to cultivate the appropriate skills and competencies for Managers or for dedicated personnel, so as to resolve the softer cases for the good purpose of the service and with the application of “Mediation procedures”.As it is stated by Bush and Folger: “The mediation process contains within it a unique potential for transforming conflict interaction and, as a result, changing the mindset of people who are involved in the process. This transformative potential stems from the mediation’s capacity to generate two important dynamic effects: empowerment and recognition. In simplest terms, empowerment means the restoration to individuals with a sense of their value and strength and their own capacity to make decisions and handle life’s problems. Recognition means the evocation in individuals of acknowledgment, understanding, or empathy for the situation and the views of the other” (Bush R. and Folger, 2005). Also for Bush and Folger “Mediation is an informal process in which a neutral third party with no power to impose a resolution helps the disputing parties to reach a mutually acceptable settlement” (Bush and Folger, 2009). Conflict, awkward situations, can be resolved promptly with the intervention of a third neutral party as it may be the Mediator, who through a structured process, establishes the ground rules, listens to the story from the perspective of each of the disputants, offers to each of them a summary of what he or she has said, helps the disputants identify the problems, brainstorm solutions, and, ideally, agrees upon a solution.The significance of Mediation has become already recognized in the sector of Education where especially in France (Souquet, 2013) (along with other countries such as in North European countries, Germany, Finland, Belgium, etc., as it is stated by Nylund, A., Ervasti, K. Adrian, L. Editors, 2018), a Mediator was appointed in each Office and each Academic Inspection and a body of mediation was created, composed of educational staff and students in each High school. The successful resolution of conflict issues and problems of early school drop outs through the mediation have led to the education of 10.000 Mediators every year in Finland in this specific educational sector.In the next chapter, we will present research that took place in the Greek public administration, which gives evidence that there is great importance to deal with conflicts as they are considerably affecting performance in the public sector.

3. Case Study: Dealing WITH Conflicts in the Public Sector

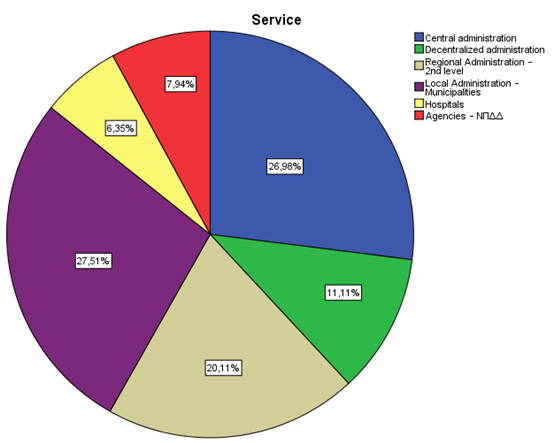

- This research had taken place in January 2018 and the main focus questions were:• “To what degree do civil servants get implicated in a conflict situation?”,• “What kind of conflicts we are referring to?”,• “What are the consequences for performance when the handling of conflict situations is not the most appropriate one?”, “Do conditions exist in order to foster a climate of consensual agreement between parties and to facilitate the application of this procedure for people who are expert on mediation?The interrelations between a set of independent variables that are examined are: the impact that conflicts and tensions have on organizational performance, the role of Managing to its resolution; the emergence of a need to tackle conflicts through a mediation process; the fact that there is a need to eliminate conflicts’ that may emanate by the disciplinary process.The aim of this study is to illustrate in depth those factors that trigger conflicts in the working environment of Greek public administration, to make a statement about the conditions of the working environment in the Greek public administration and to demonstrate at what extent there can be any intervention towards eliminating their effect on maladaptation of civil servants to the mission of the administration. The final conclusions that are drawn expose that the current deal with these situations needs to change and to give place to more flexible methods, such as the Mediation in which the Directors play a fundamental role.The survey was emailed to civil servants in the central administration as well as to local government, to health services and to decentralized administrations. A total of 500useable surveys was received after the survey was emailed to representatives of the administration.The questionnaire had two variations, one made for Directors/Section Managers and a second one for civil servants. For the first category, Directors/Section Managers came from various administrations: 27.51% from the municipal level, 26.98% from central administration, 20.11% from the regional level (second level of local administration), 6.35% of hospitals, and only 7.94% of the agencies and public authorities. The great majority of 97.35% are permanent civil servants, and only 1.06% are temporary staff and also the rest of them are appointed by the government for a short term mission.

| Figure 1. Percentage of Directors/Section Managers that participated in the research |

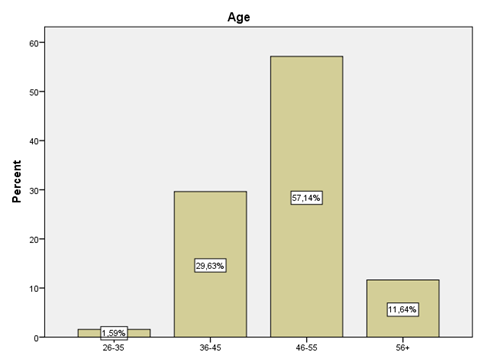

| Figure 2. Distribution of ages οf Directors/Section Managers |

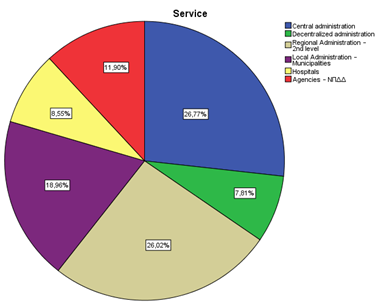

| Figure 3. Distribution of participants in the various administrations |

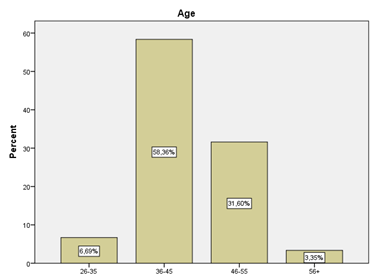

| Figure 4. Demographic characteristics of employees |

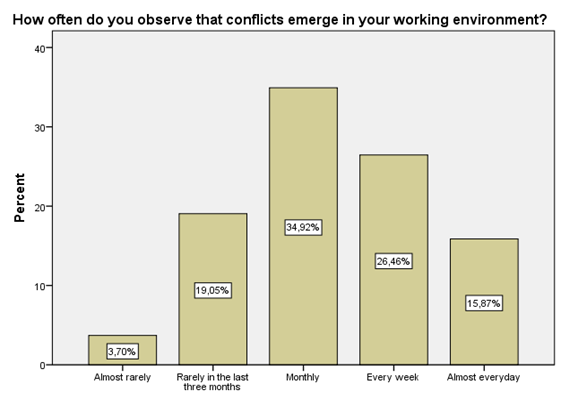

| Figure 5. Frequency of appearance of conflicts for Directors/Section Managers |

| Figure 6. Frequency of appearance of conflicts for Directors/Section Managers |

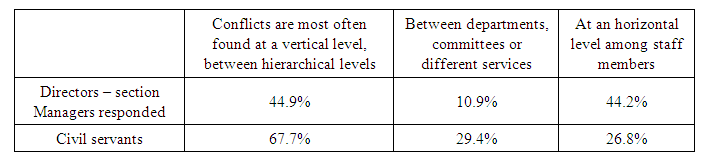

| Figure 7. Appearance of conflicts between layers of the hierarchy or horizontally |

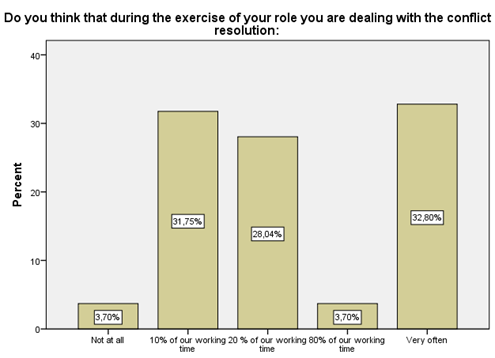

| Figure 8. Time consuming of the resolution of conflicts for Directors/Section Managers |

| Figure 9. The personnel that is implicated in a conflict |

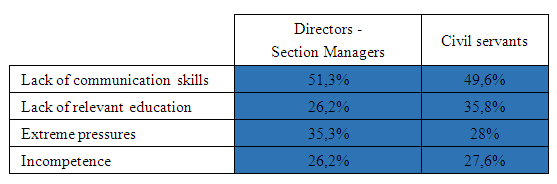

| Figure 10. Sources of conflicts for the two main categories |

| Figure 11. Reasons that explain why conflicts could not be dealt effectively |

| Figure 12. Consequences of conflicts in the workplace |

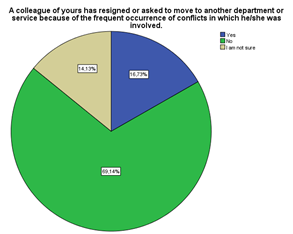

| Figure 13. A colleague that has asked to change his/her post due to conflicts |

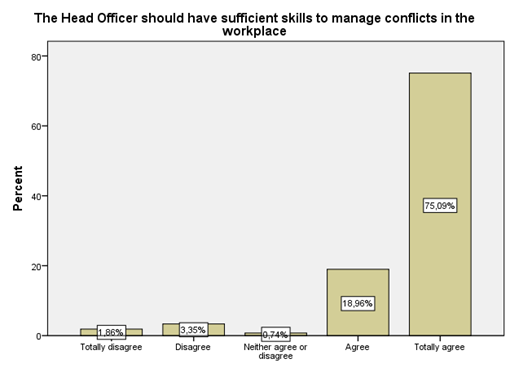

| Figure 14. How important it is to train Managers on Mediation and conflict resolution |

4. Discussion

- The goal of this research was to reach a more definitive conclusion as to: 1) the relationships among the organizational conflicts and the need to address them in a more systematic and effective way through modern tools such as the Mediation mechanism, 2) the negative consequences that the organization suffers from as long as persisted conflicts are not dealt effectively (that may even end to rotate people between departments!). Through the quantitative research it was argued that conflicts exist and persist and a more systematic approach is needed in order to overcome their negative effect on performance. Also, it was recommended to build capable administratively public organizations that will be legitimate, and at the same time, will maximize their performance and will create a warm and friendly environment for the personnel and the users. By recognizing the need to tackle disagreements and conflicts in a workplace, we take the first step towards creating a “best workplace” that is the one that does not underestimate the negative climate and is researching the following issues whenever it is needed: What are the main sources of conflicts?; in which department/section/area conflicts appear and why?; what role the affected Managers have played so far?; what are the opinions of those who are implicated (directly/indirectly) to the problem?; what does or omits to do the Senior Management for these cases?; etc.. Also, in case of disagreements and/or conflicts the negative consequences are also important to be acknowledged, as the ones that were depicted in the presented research: “Negativity and unpleasant working climate”; “disorganization of the service”; “division of the personnel into subgroups”; “energy waste”; “stress”; “failure to cooperate or application of passive resistance”, etc. That way of lateral “self-assessment” of public organizations is a modern tool to be further more analyzed. In this research the main objective was to introduce, to discuss about the need to deal more systematically with the subject of conflicts in workplace and to propose the institutionalization of a formal procedure through the mediation that even though it can be competitive to the disciplinary method (that up to now in some administrations had the privilege to handle minor disagreements) it can be far more effective and accepted by the personnel.

5. Conclusions

- Organizations are strongly dynamic communities and no one can argue that they formulate a perfect, peaceful working place where all members share the same vision and objectives and cooperate towards their accomplishments easily. It is very important to accept that disagreements are valuable criteria of a healthy and productive environment where every voice is heard and people do not hesitate to raise issues whenever they believe it is important to share their divergent view. Stability and a well-coordinated chain of command were the main components of the traditional top down organizational form in public administration, in which staff had only one specific assignment and procedures were clear cut vertically. The U organization gave place to a more horizontal (matrix) way of formulating policies and employees became multitask and multi oriented to undertake various missions at the same time. The emphasis of new public organizations to openness and inclusiveness by conducting an open dialogue with various other organizations, stakeholders, NGOs, social organizations, etc., or by cooperating with the private sector, etc. (Rhodes, 1996), at national and international level, led to the prevalence of a strong belief that the environment in organizations is far more dynamic and receptive of different options that may often lead to disagreements or conflicts between its members or with representatives of other organizations, etc.. The management of procedures has revealed more opportunities for conflicts and staff has become aware of the issue.Indeed, the challenges to face conflicts and disagreements are strong and organizations must undertake a specific and appropriate model of processing towards those harmful situations that, as long as they persist, they consume valuable working hours, distract the personnel from its goals and affect performance. Furthermore, the traditional discipline procedure as well as the legalism and formalism of organizing the work has made it a hard endeavor to change this optic and to let other disciplines interfere in management, as it is the Mediator, or the Manager himself. In old public administration misunderstandings and violations were considered a priori as parts of a solid and rigorous procedure that starts with the investigation and triggers an official disciplinary procedure that is the only one being objective. Recent developments and the increase of the appearance of these phenomena has led to the conclusion that this old paradigm is no longer effective and must change in order to ameliorate the responsiveness of the organization to new challenges. One of the major benefits identified through this research is that conflicts need to be addressed differently and more systematically, especially through the Mediation procedure, as they have a great impact on the performance of public services and on the implementation of reforms.

6. Further Research

- Conflict’s management and misconducts in Greek public administration or in European administrations merit the involvement of researchers that could propose adequate solutions and facilitate the implementation of current reforms. The topic of management of conflicts in a workplace has been quite analyzed in the international literature review. What is needed to do furthermore is to innovate by introducing modern tools to treat effectively conflicts and disagreements, such as the Mediation technique, as one that can be effective and efficient in order to mitigate the negative consequences of these harmful situations for the personnel, the department and the organization as a whole. This new approach through the Mediation (or even the peer Mediation) means that there is a willingness to further more eradicate the loyalty of public administration to the strict legal framework and to permit more soft “managerial” methods (Whetten, D.A. and Cameron, K.S., 2007) to interfere in the traditional perception of the “way we do around things” in the public sector.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author acknowledges the support of Professor M. Theodosios Karvounarakis (University of Macedonia) as well as the provision of added assistance in the execution of the quantitative research from Mr. Georges Sidiropoulos and Mrs Aikaterini Desli.

Notes

- 1. For an in-depth analysis and typology of conflicts you may consult the paper “Models of conflict, negotiation and third party intervention: A review and synthesis” of Lewicki, Weiss and Lewin (1992).2. Saks, A., Gruman, propose that the socialization of the organization can put an end to these tensions and contribute to the creation of a warm working environment. This coincides with their proposal to put emphasis on the interpersonal skills, both between the employees, as well as between the employees and the end-users of the public administration. Also they stress the need to enhance Emotional intelligence and self-efficacy of the employees. (See: Saks, A., & Gruman, J., (2011), “Manage Employee Engagement to Manage Performance”, Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4.3. In international literature the cause of conflicts has been the object of many researches i.e. March and Simon (1958) and also Sheppard (1984) conducted researches on the different origins of conflicts weather they relate to the inter-organizational sources or intra organizational sources.4. Productivity as well as stability and adaptability are some criteria to evaluate the level of conflicts in organizations (cf. Sheppard, 1984).5. Robinson and Bennett (1995) define “Employee workplace deviance” as voluntary acts that undermine the interests of organizations and its members.6. “In Greek public administration Human resource management of the central administration has been traditionally characterized by a lack of strategic vision and near-absence of workforce planning, a short-term focus on stand-alone reforms, and the absence of linkages with other areas of public management. The reform effort in HR has run out of steam” (OECD report, 2011).7. One may argue that in the Greek public administration, there is still a tendency to work individually in a way to avoid the risk that teamwork can bring to the serenity of one’s department. As it has been described in the report of OECD for the Greek public administration: “Almost 83% of the buildings do not have a conference room. Therefore, there is a lack of places for the staff to meet either informally or formally, which hinders the development of team spirit and complicates coordination and information-sharing within and between services”. See also, Sinclair, A. (1992) “The tyranny of the team ideology”, Organization Studies 13/4: 611–626.8. In addition to the general admitted causes of organizational conflicts, there are also a number of other possible sources of conflict in Greek public administration linked to the severe economic crisis. The cutoff of 150.000 employees until 2015 has led to the dismantling of public services and in particular of peak services with high numbers of serving the citizens (i.e. IKA, OAED (Manpower Employment Organization), OAEE (Self-Employed Workers’, Insurance Organization, Hospitals, etc.). In several critical departments, the alleged deficiency in human resources due to high personnel categories and specialized qualifications (especially those entered into early retirement- retirement scheme leading to lack of ratings services-skill shortage-) is a main source of tension and labor disputes. In addition to all these negative features as it is mentioned by Mrs Triantafyllidi, I., (2015), the motivation of employees is at the lowest level.9. It should be noted that these administrative capacities are generally not available to supervisors, since the career-based system allows, by definition, the staffing of higher positions by persons who meet specific criteria, linked more to seniority and technical knowledge, rather than to the managerial competencies, such as human resources management, leadership and conflict resolution.10. In Greece the “Legal formalism, ..,whilst originally intended to protect the administration against political interference and to secure its integrity, has become excessive to the point that it renders administrative/political processes opaque and complex, providing a screen for individual behaviours that undermine the common good” (OECD, report 2011). As a result, minor issues in management cannot be solved unless there is a relevant legal document that describes in detail the relevant competence of the administration to act upon. In the central administration there have been detected more than 2.500 competences in legal documents and authorities cannot take any initiative unless they are authorized to do so. The consequences are tremendous for the effectiveness of public action.11. It is debatable whether the Civil Service Law should contain a detailed description of all offences and the corresponding sanctions which is the case in Greek public administration.12. Issues such as the creation of administrative burdens instead of their abolishment are important to be discussed in the department, but as they are part of the strict disciplinary procedure, they rarely are recalled and so the problem is perpetuated (regarding bureaucracy in this case, but also the same applies for other issues). If they were categorized otherwise as they merit be, there may have been some vital solutions to these problems. 13. The disciplinary procedure must apply the adversarial principle, e.g. the disciplinary authority in charge of conducting the procedure and imposing the relevant sanction, must respect the right of civil servants to defend themselves against the charges and that the civil servants are allowed to submit their arguments and proofs. For instance, in the U.S.A., a Federal regulation requires that agencies provide employees with due process rights when imposing disciplinary sanctions: 30 days’ notice of the agencies intent to take disciplinary action and sufficient detail of the alleged wrongdoing, an opportunity to reply to the allegations both orally and in writing before a management official with higher authority than the management official initiating the sanction, a right to be represented by an attorney or other representative of the employee’s choice (including union representation), the right to see the material/evidence the agency is relying on to impose the sanction, and the right to a decision from a higher level management official identifying the employee’s multiple appeal rights Cardona, F., (2003) “Liabilities and discipline of civil servants”, SIGMA papers.14. “Proportionality means that the penalty imposed shall be proportionate to the gravity of the offence taking into account the circumstances. In order to ensure fairness and equal treatment across cases, it may be useful to establish in legislation a grading of offences and the appropriate penalties, while ensuring a sufficiently wide range of possible sanctions to punish misbehavior” (SIGMA papers).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML