-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2019; 9(1): 1-9

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20190901.01

Employee Readiness to Change and Its Determinants in Administrative Staff of Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia

Mintamir Mekonnen Workeneh1, Amare Sahile Abebe2

1Department of Finance, College of Agriculture, Bahir Dar University Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

2Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, College of Education and Behavioral Sciences Bahir Dar, University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Amare Sahile Abebe, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, College of Education and Behavioral Sciences Bahir Dar, University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The main concern of this study was to investigate employee readiness to change and its determinants with particular reference to the administrative staff of the Bahir Dar University. Data collected from 367 sample participants from nine campuses using stratified random sampling method. Scale questionnaire employed as data collection instruments. The results indicated that administrative staffs had higher perceptions of readiness to change in the emotional, cognitive and intentional components. Moreover, perceptions of a history of change, participatory management, and quality of communication positively correlated to readiness to change. There were statistically significant contribution of a history of change, participation management and quality of communication to readiness to change. In conclusion, management bodies should work more to bring about good feelings about the change, all members of the staff need to be communicated regularly, information should be clear, transparent and progressive.

Keywords: Readiness for change, Determinants of change, History of change, Trust in top management, Participatory management, Quality of change communication

Cite this paper: Mintamir Mekonnen Workeneh, Amare Sahile Abebe, Employee Readiness to Change and Its Determinants in Administrative Staff of Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20190901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Several studies observed that management usually focuses on the technical elements of change with a tendency to neglect the equally important human aspect (Backer, 1995; Beer & Nohria, 2000; Bovey & Hede, 2001; George & Jones, 2001). Despite the popularity of the technological change approach, other studies have demonstrated that adopting such perspective does not always lead to successful change (Beer & Nohria, 2000; Clegg & Walsh, 2004). An important reason why many organizational changes result in outright failure is because of an underestimation of the powerful role of the human factor in organizational change (Prosci, 2007). Therefore, in order to successfully lead an organization through major change, it is important for management to consider both the human and technical aspects of change. Organizational change is simply doomed to fail (Antoni, 2004; George & Jones, 2001; Porras & Robertson, 1992). Researchers in the area of organizational change have begun to direct their observation to a range of variables that may foster change readiness (e.g., Armenakis, Harris & Mossholder, 1993; Armenakis et al., 2007: Chonko, Jones, Roberts, & Dubinsky, 2002; Eby, Adams, Russell, & Gaby, 2000; Jones, Jimmieson, & Griffiths, 2005; Oreg, 2006; Jimmieson, Terry & Callan, 2004; Jones, 2006).According to Holt and colleagues (2007a) readiness for change is manageable. Several organizational development models (Kotter, 1995; Lewin, 1951; Mento, Jones, & Dirndorfer, 2002) suggest that the potential sources of readiness for change lie both within the individual and the individual’s environment. In addition, the instruments appear to measure readiness for change from several perspectives, namely the process, the context, the content and individual attributes (Holt, Armenakis, Field, & Harris, 2007b). The importance of these four drivers of change has been widely acknowledged (Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Bommer, Rich, & Rubin, 2005; Judge, Thoresen, Pucik, & Welbourne, 1999). Studies that considered the combined effect of these four enablers, however, are somewhat limited in their scope (Eby et al., 2000; Oreg, 2006; Wanberg & Banas, 2000). The results are often based on data obtained in a single organization or sector, this often leading to very specific conclusions about the impact of change context and change process factors.Based upon these inadequacies, Special attention is drawn to the combined influence of the context and process factors of the change readiness. A better understanding of how employees perceive the context and the process of change will advance our knowledge of the central role change readiness plays in the management of programs of planned organizational change.According to Bouckenooghe, (2008) explored the relationship between psychological climate of change (i.e. Trust in top management, history of change, participatory management, and quality of change communication) and readiness for change. He employed a large scale survey administered in 53 Flemish public and private sector organizations; he collected a total of 1,559 responses. Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypotheses. A positively perceived change history, participatory management and high quality change communication had positive correlations with trust in top management. Trust in top management did not mediate the relationships between those three change climate dimensions and the outcome variables (i.e. Emotional, cognitive and intentional readiness for change). In addition, it was found that history of change and quality of change communication shaped organizational members’ emotional and cognitive readiness for change. The complex interplay between people’s cognitions, feelings and their intentions about organizational change confirms the need to consider readiness for change as a multi-faceted construct.This research aims an investigation into employee readiness to change and its determinants with particular reference to the administrative staff of the BDU. This topic was selected in an attempt to find out to what extent change readiness is influenced by determinants such as trust in top management, history of change, participatory management, and quality of change communication currently perceived by employees of the BDU.The justification behind selecting the topic was an expansion in various areas including new work innovations in the context of Ethiopian universities was commenced two decades ago, which BDU is not an exception of the change initiatives. But what initiated the investigator of this study to date was no investigation carried out so far related to employees’ readiness for change and determinants their perception on the overall work efficiency particularly in BDU. Investigating this problem may provide knowledge how employees perceive readiness to change so as be familiar with the change and attain to its realization and this in turn lead to understand the benefit of change that could promote worker efficiency and support the newly launched change initiatives and find out the main determinants employee ascribe for the readiness of change. This study explores employee readiness to change and its determinants with particular reference to the administrative staff of the BDU.

2. The Problem

- Success of change depends on the organization’s ability to make all their employees participate in the change process (Olive, 2009). The dynamic work environment today requires frequent changes both in the way organizations operate and in the organizational structure. Organizations today operate under increasing demands for change. According to Burnes, (2004) change is an ever-present feature of organizational life, both at an operational and strategic level. Therefore, there should be no doubt regarding the importance to any organization of its ability to identify where it needs to be in the future, and how to manage the changes required in getting there. From a practical point of view, there is a clear need for an integrated and holistic framework to help top management think about how to formulate, implement and sustain a fundamental change in complex organizations like Ethiopian Universities.With regard to trust in top management literature, trust describes as a concept that represents the degree of confidence employees have in the goodwill of their leader, specifically the extent to which they believe that the leader is honest, sincere, and unbiased when taking their positions into account (Folger & Konovsky, 1998; Korsgaard, Schweiger, & Sapienza, 1995). Trust in top management is found to be critical in implementing strategic decisions (Korsgaard et al., 1995) and an essential determinant of employee openness towards change (Eby et al., 2000; Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1999). One of the most difficult things employees experience when confronted with change is the uncertainty, the ambiguity, the complexity and the stresses associated with the process and outcomes (Difonzo & Bordia, 1998). Trust can reduce these negative feelings, because it is a resource for managing risk, dispersing complexity, and explaining the unfamiliar through the help of others (McLain & Hackman, 1999). Therefore, readiness for change will be strongly undermined if the behavior of important role models (i.e. Leaders) are inconsistent with their words (Kotter, 1995).Concerning the history of change research has tended to ignore time and history as critical context factors that affect organizational change processes (Pettigrew et al., 2001). Few studies actually considered an organization’s change history as an antecedent of readiness for change. Despite the limited interest in this contextual force, indications revealed that employee’ perceptions of past change failures may limit or even doom efforts at new organizational changes. For example, Reichers et al. (1997) noted that people tend to develop cynicism about new organizational change, due to negative change experiences (Reichers et al., 1997; Wanous et al., 2000). Studies showed that unsuccessful change history is negatively correlated with the motivation or effort put into making those changes. As a consequence, one of the aims of this study is to explore the effects of organizational change history on employee change readiness. The effects of organizational change history can be in terms of the schema theory (Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Lau & Woodman, 1995). This perspective helps us in the understanding of how beliefs or expectancies about the likelihood of successful organizational change become crucial drivers of employee motivation to change.Leana (1986) expresses a view that participation management is a special type of delegation by which management shares authority with employees. Early and Lind (1987) considers this process as a means by which employees are given a voice to express themselves. This style of management affords employees the opportunity to gain some control over important decisions and in fact is, a way designed to promote ownership of plans for change (Manville & Ober, 2003).With regards to quality of change communication, writers claim that communication of change is the primary mechanism for creating readiness for change (Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Bernerth, 2004; Mille et al., 1994). Communication is vital to the effective implementation of organizational change (Schweiger & Denisi, 1991; Richarison & Denton (1996). Poorly managed change communication often results in widespread rumors, which often exaggerate the negative aspects of the change and build resistance towards change. Thus the quality of communication will often determine how employees fill in the blanks of missing change information. If the quality is poor, people tend to develop more cynicism (Reichers et al., 1997).In Ethiopia several changes in organizational structure and business process have been taken place in the past in civil service organization in general and educational institution in particular. Changes in structures such as business process reengineering (BPR), Balanced Score Card (BSC) and Kaizen are some of the major change initiatives introduced. So far little or scanty studies have been conducted as to how these changes in organization brought about workers and organizational efficiency in the context of higher learning institutions in relation to administrative staff. At present, there is a gap in the literature relative to assessing change readiness of employees and major determinants in the context of the Ethiopian higher learning institution particularly BDU.Furthermore, the extent to which determinants of readiness for change, for instance trust in top management, history of change, participatory management, and quality of change communication affect human resources Bouckenooghe (2008). Local studies conducted by (Yared, 2013) in Science and Technology University in Ethiopia on employees’ perception towards organizational change indicated a further study in Ethiopian higher learning institute to see how employees react to changes undertaken in organization such as University context as worthwhile. Presently, it is less evident whether research fully attested the determinants influence employees’ readiness for change in a learning institute of developing nation like Ethiopia. Additionally, the investigators of the study unaware of a literature focused on employees change readiness and its determinants in the Ethiopian context. Studying this contribute to a better understanding of how employees perceive change readiness and its determinants in the process of change, and in turn to advance knowledge of the role change readiness plays a requisite for management programs of planned organizational change in Universities.The general objective of this study is to investigate into employee readiness to change and its determinants with particular reference to the administrative staff of Bahir Dar University, one of the first generation universities in Ethiopia.

3. Objective

- The study was carried out with the following objectives• To assess the perceived level of change readiness and its determinants among administrative staff• To examine the relationship between the determinants and perceptions of change.• To determine the extent to which determinants contribute to the total variance of employee readiness to change.Scope of the studyThe present study aims to assess employee readiness to change and its determinants of the administrative staff of the BDU. It covers employees working in the university. The employees belong to different colleges and faculties such as officeholder, clerical staff and sub-staff. The study explores employee readiness to change and its determinants among employees working in the university and examines it in university organization context, such as, readiness to change, determinants of readiness to change, for instance trust in top management, a history of change, participatory management, and quality of change communication.Above all, it can be said, that a readiness to change is very important for the individual employee and as well as an organizational apprehension. In today’s world of work entailed with changes that derived from innovation, technology and in the changing nature of the job, differential expectations, new management practices, demands for specialized skills, etc., the process of change is inevitable in the existence and growth of any organization. It depends on the employees need to change with the changing conditions of the organization. As a result, determinants of readiness of change affect employees’ perception and make them internalize and accept change efforts.

4. Methods

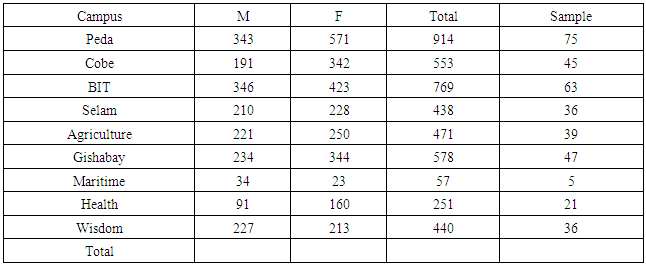

- The correlation approach was considered more appropriate to understand the phenomenon of change readiness and its determinants on university employees administrative staff. The target populations of the study consist of 4471 administrative staff of Bahir Dar University spread over nine colleges, faculties, institutes and school. Out of the total number 367 administrative employees taken as the sample of the study. The sample participants selected based stratified random sampling from their working campuses.

4.1. Dependent Variables

- The instrument for data collection was a questionnaire. The readiness to change variables measured using a scale adapted from Metselaar (1997) and Oreg (2006). The scale consisted of emotional dimension (EMORFC), the cognitive dimension (COGRFC), and the intentional dimension (INTRFC) each consist of three items.

|

4.2. Independent Variables

- Trust in top management assessed with a three-item scale based on instruments developed by Albrecht and Travaglioni (2003), and Kim and Mauborgne (1993). The internal consistency of this scale was found to be good The measurement of the second context variable ‘history of change’ adapted from Metselaar (1997) and is comprised of four items (α= 73). The third context variable ‘participatory management was measured with a six-item scale. The reliability of this scale was found to be more than adequate (α=.78). Finally, quality of change communication measured (QUALCOM) with six items and adapted from Miller et al. (1994). This scale also yielded a good internal reliability (α =. 83). Measurement of independent and dependent variables measured with a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 to 5 (Strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) when the items are worded positively and strongly disagree (5) to strongly agree (1) when the items are phrased negatively (reverse scoring). The questionnaire translated into Amharic (local) language by the language instructors to avoid the language barrier.

4.3. Data Analysis

- The responses classified into themes and sub themes. Data analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean and SD), correlation and regression.

4.4. Ethical Consideration

- Participants gave their informed consent to participate prior to seeking their responses. The researchers tried to do this by requesting permission from the heads of the management of the university through discussion. Finally the participants’ agreement obtained after being informed the purpose of the study.

5. Results

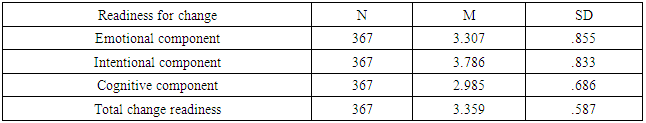

- As indicated in Table 2 the results of descriptive statistics demonstrated that the mean score of the emotional components of readiness for change is 3.307 and SD is. 855. This result shows that administrative staffs exhibited higher levels of perceived emotional readiness for change The mean score of intentional components of readiness for change is 3.786 and SD is .833. This result shows that administrative staffs, higher levels of perceived intentional components of readiness for change. The mean score of a cognitive component of readiness for change is 2.985 and SD is .587. This result shows that administrative staffs had a moderate level of perceived cognitive components of readiness for change. The mean score of total readiness for change is 3.359 and SD is .587. According to Field (2009) interpretation the mean score below 2.5 was considered as low, the mean score from 2.5 up to 2.99 considered as moderate and the mean score above 3.0 considered as high.

|

|

|

|

6. Discussion

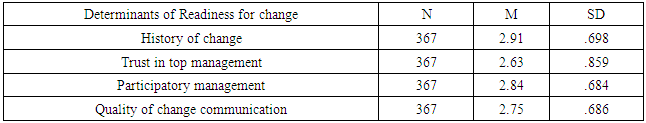

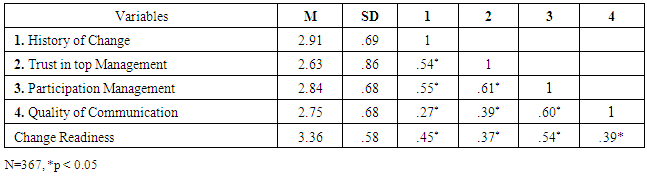

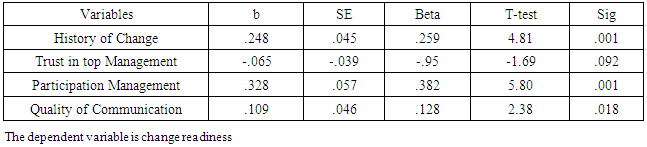

- The administrative staff have higher levels of perceived emotional components of readiness for change. On the other hand the result shows that administrative staffs have moderate level of perceived cognitive components of readiness for change. The interplay between the different components of readiness for change confirmed the necessity for treating readiness for change as a multifaceted concept (Holt et al., 2007a; Piderit, 2000). This finding suggests that readiness is manifested through different channels (emotion, thinking and intention), indicating that employees’ readiness for change is the result of a complex interplay between three forces of psychological functioning. The relationships between emotional and cognitive dimensions and emotional and intentional dimensions partially support the Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (1991). This stipulates that people develop feelings and cognitions about the benefits and losses associated with engaging or not in change. Depending on the favorableness of this evaluation process, employees will have a stronger or weaker intention to engage in change. In short, intention to change is determined by how people feel and think about the change. On the contrary, Bovey and Hede (2001) but aligned with George and Jones’ process model of individual change, affect is considered an impetus for activating cognitions about change (George & Jones, 2001). Thus, emotions motivate the cognitive activity and behavior to deal with an emotion-triggering situation like change.The study also assessed the perceived level of each determinant of change readiness among administrative staff. Based on the interpretation adopted from the Field (2009) recommendations. The results show that majority of administrative staffs perceived past changes as moderately successful.With regard the history of organizational change research has tended to ignore time and history as critical context factors that affect organizational change processes (Pettigrew et al., 2001). Few studies actually considered an organization’s change story as an antecedent of readiness for change. Despite the limited interest in this contextual force, it seems an indication that employee’ perceptions of past change failures may limit or even doom efforts at new organizational changes. For example, Reichers et al. (1997) noted that people tend to develop cynicism about new organizational change, due to negative change experiences (Reichers et al., 1997; Wanous et al., 2000).Similarly, administrative staffs perceived trust in top management as moderately successful. With regard to trust in top management literature trust is described as a concept that represents the degree of confidence employees have in the goodwill of their leader, specifically the extent to which they believe that the leader is honest, sincere, and unbiased when taking their positions into account (Folger & Konovsky, 1989; Korsgaard, Schweiger, & Sapienza, 1995). Trust in top management is found to be critical in implementing strategic decisions (Korsgaard et al., 1995) and an essential determinant of employee openness towards change (Eby et al., 2000; Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1999).Correspondingly, the majority of administrative staffs perceived participation of the management as moderately successful. Through a variety of experiments at the Harwood Manufacturing Plant observed that groups that were allowed to participate in the design and development of change had a much lower resistance than those who did not. Leana (1986) expresses a view that participation is a special type of delegation by which management shares authority with employees. Early and Lind (1987) considers this process as a means by which employees are given a voice to express themselves. This style of management affords employees the opportunity to gain some control over important decisions and in fact is, a way designed to promote ownership of plans for change (Manville & Ober, 2003).Likewise, the majority of administrative staff perceived quality of communication as moderately successful. With regards to Process Factors: in Quality of Change Communication the challenge that constantly returns in all change projects are management’s struggle to overcome employees’ persistent attitude to avoid change. The answer not only lies in a participative leadership style of management, but also in communication with organizational members Indeed, several authors claim that communication of change is the primary mechanism for creating readiness for change (Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Bernerth, 2004; Miller et al., 1994). Communication is vital to the effective implementation of organizational change (Schweiger & Denisi, 1991). Poorly managed change communication often results in widespread rumors, which often exaggerate the negative aspects of the change and build resistance towards change. Thus the quality of communication often determines how employees fill in the blanks of missing change information. If the quality is poor, people tend to develop more cynicism (Reichers et al., 1997).With regard to the relationship between determinants and perceived levels of readiness to change significant positive correlation observed between history of change and perceived levels of readiness to change. In the study of cynicism about organizational change Wanous, Reichers, and Austin (2000) noted that history of change is correlated with the motivation to support change. These authors suggested that the higher the pre-existing level of cynicism about organizational change, the more executives need to confront and discuss previous failures before moving ahead.Similarly, significant relationship between trust in top management and perceived levels of change readiness observed. In organizations where trust in top management exists, and where change projects have been implemented successfully in the past, organizational members are more likely to develop positive attitudes towards new changes. A vast amount of literature denotes that trust of organizational members in their leader is a salient antecedent of people’s cooperation in implementing strategic decisions and an essential factor in predicting people’s openness toward change (Eby et al., 2000; Korsgaard et al., 1995; Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1999). Trust in top management is critical in shaping people’s responses to change, because it helps to reduce the change related feelings of stress and uncertainty, both major inhibitors of readiness for change.Likewise, significant relationship between participation in management and perceived level of readiness to change observed. According to Eby et al. (2000) perceived participation at work or what we call participatory management may affect people’s reactions to change. Although several sources indicated that a limited access to participation can lead to increased levels of cynicism about change and resistance to change (Reichers, Wanous, Austin, 1997), there is no clear consensus about the effect of participation.Although the results are mixed, it has been shown that participatory of the management has an impact on job attitudes and motivation (Leana et al., 1990) Greater levels of participation and involvement allow individuals to have wider repertoires of activity and control over the dynamic and complex environment in which they work. In other words, an outcome of increased participatory management is employee empowerment, which gives employees the ability, the authority, and responsibility to make decisions. In short, stronger levels of participation contribute to a sense of control in one’s job which in turn contributes to a higher self-efficacy in dealing with uncertain conditions or challenges like change. Thus, it is expected that if employees perceive the work environment as participative, they are likely to be more receptive to organizational change, and in turn, are going to be more ready for change.Correspondingly, significant correlation was observed between the quality of the communication and perceived levels of readiness to change. In the seminal work on creating readiness for change, Armenakis et al. (1993) mentioned several influence strategies that can be used by change agents to increase readiness for change. One of the foremost strategies is persuasive communication, which is mainly a source of providing explicit information about the reasons and urgency for change. Several authors indicated that communication is a vital mechanism for the effective implementation of organizational change (Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Schweiger & Denisi, 1991). Poorly managed change communication often results in Widespread rumors, which provides a fertile ground for the development of negative feelings and beliefs about change. Briefly, what is said matters, and the rigor and consciousness in the communication of change are what differentiates a successful change from one derailed by resistance and uncertainty (Ford & Ford, 1995; Miller, Johnson, & Grau, 1994).

7. Conclusions

- From the findings of the study it was understood the administrative staff have a high level of perception of change readiness. This implies whatever a change may be introduced it is likely to be accepted by the staff and they strive to perceive change efforts as positive. On the other hand, the determinants are moderately effective to bring change on the part of staff, whatever the change comes from the trust in top management, whether the quality of communication is good or not, participation of management is high or low and history of change is known or unknown. The determinants of change positively related to readiness for change. This implies that the determinants of change readiness positively impact on employee readiness to change. This shows the determinants have a power to predict employee readiness to change.It seems that the staffs have a positive perception of change readiness and this should be encouraged, supported and motivated by concerned bodies. The change needs to refreshing, bring good feeling about the change, make the staff experience the change as a positive process. Therefore, the management body should clearly create awareness of a history of change and its importance, the top management should be trustful to employee about the change to be effective.Concerned management body of the university should think an organization has always been able to cope with the demands of new situations; they have to orient the staffs that past changes have generally been successful. The management should fulfill its promises and consistently implement changes. Decision -making concerning change related matters are taken in consultation with the staff members to effect change and provide sufficient time for consultation. Problems should be openly discussed, the two way communication between the management and the staff need to be transparent., therefore the management should be aware of the history of change before change initiatives are implemented, and participates profoundly to bring about the desired change and the communication regarding change should be informative, clear and enlightening.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This Study supported by the Bahir Dar University. The writers of this paper extend their appreciation to the university at large.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML