-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2018; 8(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20180801.01

How Would Your Employees be Charged? The Study of the Incentive Practices and Employees’ Charged Behavior in Foodservice Companies

Joseph Si-Shyun Lin1, Chien-Chung Chen2

1Department of Restaurant, Hotel and Institutional Management, Fu-Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, R. O. C.

2Department of Tourism, Shih-Hsin University, Taipei City, R. O. C.

Correspondence to: Joseph Si-Shyun Lin, Department of Restaurant, Hotel and Institutional Management, Fu-Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, R. O. C..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Foodservice operators have being facing challenges from competitors as well as consumer’s demands along with the growing market. Customers in particular are more than ever before looking for new and unique experiences. To meet these challenges, company has to emphasize and accommodate ‘‘innovation’’ in their business to provide alternative and better services as compared to their competitors. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between employees charged behaviors and the incentive practices implemented by the companies, to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of the practices on the arouse of employee’s charged behavior. Results of this study showed that foodservice companies have implemented incentive practices to provide their employees the channel to bring out new ideas during their work. Among the practices, ‘Vision communication’ was the most implemented one in foodservice companies, while ‘Study group’ was the least implemented. The results also confirmed that the implementation of incentive practices increased the charged behavior of employees. However, the practices with higher level of implementation did not necessarily showed higher correlation to employees’ charged behavior. The practice of ‘15% time program’ was found to have the highest impact to the employees’ charged behavior. Managerial implementations were suggested to the foodservice company, in order to increase their employees’ charged behavior and, therefore, enhance their service innovation performance.

Keywords: Incentive practices, Charged behaviour, Employee, Foodservice

Cite this paper: Joseph Si-Shyun Lin, Chien-Chung Chen, How Would Your Employees be Charged? The Study of the Incentive Practices and Employees’ Charged Behavior in Foodservice Companies, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20180801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The tourist industry in Taiwan has being growing with the demands from domestic and international tourists, as well as the support from the government. The number of visitor to Taiwan has grown from three million in 2005 to more than nine million in 2014. The number of visitors reached its peak at over ten million in 2016. It is believed that the influence of domestic factors, the higher incomes, the increased number of family with dual incomes, and the increased opportunities of dining out, also contribute to the growth tourist in Taiwan. The foodservice industry, which play an important role in tourist activities, is also growing rapidly. The foodservice industry had the revenue of more than forty three thousand billion NT dollars in 2016 as compared to the number of twenty nine thousand billion NT dollars in 2005, and is expected to grow. With the growing market, the foodservice operators have faced variety of challenges and competitions. Customers in particular are more than ever before looking for new and unique experiences. Therefore, the players in the foodservice sector have to grasp their customers by satisfying their demands (Panayides, 2006; Vang & Zellner, 2005). To meet this challenge, companies have to emphasize and accommodate ‘‘innovation’’ in their business. Innovation becomes the core and an important strategy to have better performance and be successful for the company (Tajeddini, 2010). The innovation may include the development of innovative products or services to attract customers, or a new business model in the industry or the upgraded system for their employees, to provide alternative and better services than their competitors (Chang, Gong & Shum, 2011; Jones, 1995; Ottenbacher & Gnoth, 2005; Huse, Neubaum & Gabrielsson, 2005; Sandvik, Duhan & Sandvik, 2014; Vang & Zellner, 2005) and increase level of loyalty of their customers (Anderson, Fornellet & Lehmann, 1994; Grissemann, Plank & Brunner-Sperdin, 2013).Researchers have indicated that the ‘Supply-Value fit’ from the theory of ‘Person–Environment fit, P–E fit’ can be effectively adapted in study of the relationship between the psychological state of individuals, the climate of organization and the climate of creativity in the company (Choi, 2004). It’s indicated that a higher performance of innovation was expected when the organizational climate of creativity was provided and recognized, which is high level of ‘Supply-Value fit’ between employees and organization (Choi, 2004). Therefore, this study explored the relationship between employees’ charged behavior and the incentive practices implemented by the foodservice companies. The feasibility and effectiveness of the incentive practices were examined to provide the companies with knowledges to increase employee’s charged behavior.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Charged Behavior

- Research on high performance teams suggests a set of key behaviors and attitudes related to the behaviors of a team that lead to exceptional success in innovation (Chen, 2011; Parker, 1998; Seibert, Kraimer & Crant, 2001; Sethi and Nicholson, 2001). Sethi and Mocholson (2001) indicated that, charged behavior, is a higher order variable, which means that it is comprised of a number of component dimensions, which are identified as enjoyment, commitment, open information sharing, challenging ideas, and company (Chen, 2011; Sethi and Nicholson, 2001). The charged-behavior team exhibit loyalty to the task and team members are committed to the project; members in such teams enjoy their task and have fun; moreover, they translate their drive and commitments into collaborative action, that is, free challenging of each other’s and the team’s ideas, and demonstrating cooperative behavior. It is suggested that outcome interdependence and interdepartmental connectedness are related to new products’ market performance only through charged team behavior. This means that joint rewards and reduced functional boundaries only help product outcomes to the extent that they create climate conductive to the development of charged behavior in the team (De Dreu, 2007; Sethi & Nicholson, 2001).Sethi and Nicholson (2001) indicated that charged behavior of employee is the key effect in new product development. The highly charged employees demonstrated better innovation behaviors as compared to less highly charged employees (Chen, 2011; Parker, 1998; Seibert et al., 2001).

2.2. Company Incentive Practices

- Hu, Horng and Sun (2009) discovered that organization knowledge sharing and team culture are essential to the service innovation in the hospitality industry. De Jong and Den Hartog (2007) in their study of the influence of leaders on employees’ innovation behaviors, they identified 13 leader and organization behavior constructs that are influencing either idea generation or application behavior of the employee. Nieves and Segarra-Ciprés (2015) found that both the internal sources and external change play influential roles in driving the managerial innovations in hotel industry in Spain.It is believed that some of the organization and leader’ behavior is more general in nature (e.g. consulting, delegating). Other behaviors are more directly at stimulating employees’ idea generation and/or application efforts (e.g. providing resources). De Jong and Den Hartog (2007) indicated that leaders typically display consulting, delegating and monitoring behavior. Leaders create a positive and safe atmosphere that encourages openness and risk taking seems to encourage idea generation and application among employees. The organization knowledge sharing, such as brainstorming activity and study group, and team culture and are essential to the service innovation in an organization (Hu, et al., 2009).Researchers found that leaders communicate an attractive vision to incorporate the role and preferred types of innovation may guide idea generation and application behavior in an organization. Also, by directly stimulating and probing employees to generate ideas, such as suggestion program, can help inducing idea generation and opportunity exploration (De Jong & Den Hartog, 2007; Shalley & Gilson, 2004). Harborne and Johne (2003) fond that a successful project leader can enhance the relationship among employees and the climate of group by non-official meeting.It is also indicated that financial rewards (such as reward system) provided by the company may, occasionally, encourage the desired behavior (De Jong and Den Hartog, 2007). However, Amabile (1988) considered that the internal motivation should be the key driver to innovation behaviors, not the money attraction. He thought the reward system should be avoided. Brand (1998) mentioned that some companies, such as 3M, allow employees to use a portion of their paid time (15-20%) to chase rainbows and hatch their own ideas. Nijhof, Krabbendam and Looise (2002) suggested that company could help their employees to focus in idea generation and opportunity exploration by removing or minimizing their routine chores.Despite the increasing research on innovation in hospitality industry, however, it mainly focus on product, process and service innovation, or its relationship with customer satisfaction and loyalty (Chen, 2011; Chen, 2012; Higgins, 1995). Few studies have addressed in depth the interaction of employee’s charged behavior, perceived innovation, and service innovation performance in the hospitality sector. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between employees charged behaviors and the company incentive practices, to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of the incentive practices on the arouse of employee’s charged behavior. The results of this study can provide more insights further to explain the influence of employees charged behaviors on their perceived innovation and service innovation performance in foodservice sectors.

3. Methodology

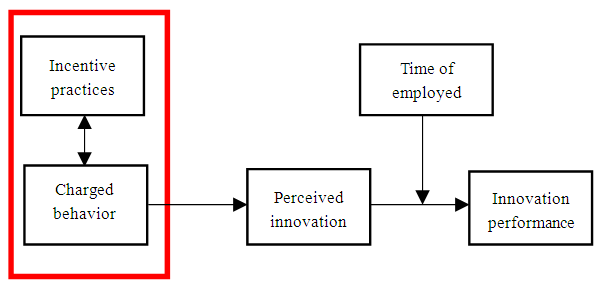

- This preliminary study only examined the relationship between employees charged behavior and the company incentive practices. It is part of the research, which tries to explore the interrelationship among employees’ charged behaviors on their perceived innovation and service innovation performance in foodservice sectors (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Frame of research |

4. Result and Discussion

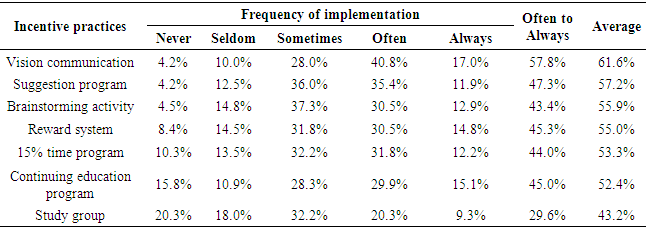

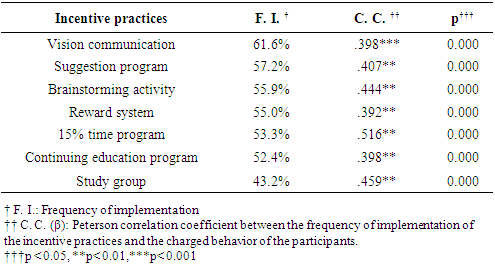

- Reliability check by Factor analysis showed that the construct displayed ample reliability with factor loadings exceeding 0.85 for the scales of charged behavior. The results of this study showed that, in general, foodservice companies have implemented incentive practices to provide their employees channels to bring out new ideas during their work. As shown in Table 1, the frequency of implementation for the practices by the organizations introduced in this study varies from 43% to 61%.

|

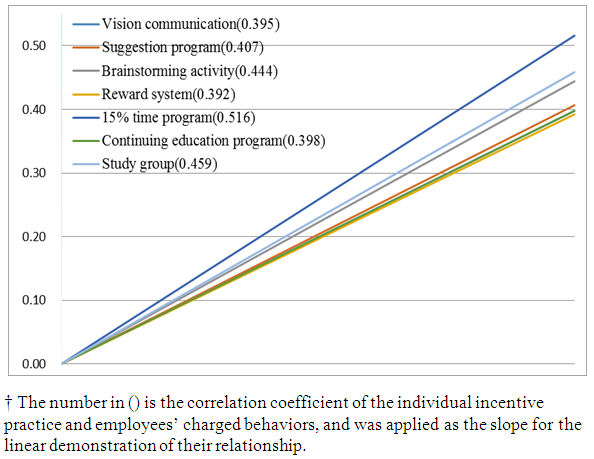

| Figure 2. The demonstration of the effect of the implemented incentive practices on employees’ charged behaviors |

|

5. Conclusions

- This study surveyed the frequency of implementation of company incentive practices in foodservice companies and examined the relationship of these practices and the employees’ charged behavior. The results revealed that foodservice companies have implemented incentive practices to provide their employees channels to bring out new ideas during their work (implementation rates ranges from 43% to 61%). Among seven incentive practices examined in this study, ‘Vision communication’ was the most implemented practice in foodservice companies. It was followed by ‘Suggestion program’, ‘Brainstorming activity’, ‘Reward system’, ‘15% time program’, ‘Continuing education program’ and the least implemented ‘Study group’.The results also confirmed that the implementation of company incentive practices resulted in increasing charged behavior of the employees. However, the practices with higher level of implementation didn’t necessarily show higher correlation to employees’ charged behavior. The practice of ‘15% time program’, which the company allows employees to use a portion of their paid time to hatch their own ideas, was found to have the highest correlation to the employee’s charged behavior, while the group of four practices, i. g. ‘Suggestion program’, ‘Vision communication’, ‘Continuing education program’ and ‘Reward system’ have lower relationship to employee’s charged behavior. It’s suggested that the nature/values of the practice, instead of the frequency of implementation, has higher influence in inspiring employee’s charged behavior.It is suggested that the implemented practices, which providing guidance, trust, joint rewards and reduced functional boundaries help creating the climate conductive to the development of charged behavior of the employees. The higher level of charged behavior of employees is expected to relate to higher innovation performance of the company. Therefore, leaders of the companies in foodservice sectors can consider incorporating incentive practices, especially the ‘private time program’, to effectively help inducing employee’s charged behavior.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML