-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2017; 7(1): 1-16

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20170701.01

Selection and Promotion of Nursing Leaders Based on Multiple Intelligences

Amanda Walder Parvari1, Sheila Hadley Strider2, Jodine Marie Burchell1, James Ready1

1Department of Business, Columbia Southern University, Orange Beach, United States

2Department of Business and Mass Communication, Brenau University, Gainesville, United States

Correspondence to: Sheila Hadley Strider, Department of Business and Mass Communication, Brenau University, Gainesville, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

As baby boomers age, the need for new healthcare leaders will emerge. Hospitals should be diligent to ensure organizational stability and eliminate derailment. Hiring and promoting leaders based on their multiple intelligences aids in securing personnel that embody the organization’s desired attributes. The problem addressed the relationship between leadership roles and demographic variables and the intrinsic multiple intelligences of nurses within the United States. This study population (N= 381) included nurses within the United States within Survey Monkey’s database. The theoretical framework of this study was Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory. The data garnered from this study can facilitate social change by aiding human resources departments in the hiring and promotion process. The results indicated a statistically significant relationship between five of the seven intelligences and leadership. The findings also conveyed a significant relationship between 13 of the 49 demographic variables and the intelligences. More research is needed to further the knowledge relative to the intelligences and the hiring and promotion processes.

Keywords: Multiple Intelligences, Leadership, Followership, Nurses

Cite this paper: Amanda Walder Parvari, Sheila Hadley Strider, Jodine Marie Burchell, James Ready, Selection and Promotion of Nursing Leaders Based on Multiple Intelligences, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-16. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20170701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Researchers have focused on the differences between leaders and followers in their respective fields. According to Carlyle’s (1841) great man theory of leadership, there is a dissimilarity between leaders and their followers’ opinions and characteristics intrinsic to each (Nelson, 2014). Carlyle’s contemporaries have pointed to the flaw in that logic and sought to determine the relationship between leaders and followers (Nelson, 2014). Leadership and followership are not mutually exclusive. The two concepts are interdependent since each relies on the other for existence (Kean & Haycock-Stuart, 2011). Long- term labor shortages are predicted within the healthcare sector due to an increasing elderly population and lack of qualified professionals to care for them (Juraschek, Zhang, Ranganathan, & Lin, 2012). As baby boomers age, the need for new healthcare leaders will emerge. Hospitals should be diligent to ensure organizational stability and eliminate derailment. Hiring and promoting leaders based on their multiple intelligences aids in securing personnel that embody the organization’s desired attributes. The problem in this study addressed the relationship between leadership roles and the intrinsic multiple intelligences of nurses within the United States. The purpose of this study was to determine if any relationship existed. The study population (N = 381) included nurses within the United States within Survey Monkey’s database. The theoretical framework of this study was Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory. The data garnered from this study can facilitate social change by aiding human resources departments in the hiring and promotion process. The results indicated a statistically significant relationship between five of the seven intelligences and leadership.

2. Multiple Intelligences

- The study of intelligence has vastly expanded since Francis Galton first believed that there was a correlation between the measurement of the human head and intelligence (Galton, 1884). Alfred Binet subsequently discovered that there was no significant correlation between the size of a person’s head and intelligence (Arnold, Riches, & Stancliffe, 2011). For many years Binet studied intelligence and, with the assistance of his mentee and colleague, Theodore Simon, established the Binet-Simon test to assess intelligence (Schneider, 1992). Gardner (1993) introduced the theory of multiple intelligences and redefined the criteria for the perception of intelligence. Before Gardner’s publication, many other theories measured the propensity of students to excel in school based on the results (Arnold et al., 2011). Gardner’s theory (1993) led to the understanding that intelligence is not merely based upon knowledge in a few areas that are conventionally linked to intelligence. Gardner stated that there are numerous intelligences not always measured by traditional intelligence testing. Gardner also theorized that each type of intelligence had an inclination towards intelligence. The traditional manner of intelligence examination will not always show the individual’s multiple intelligences. For example, many musical prodigies and athletic stars excel in their respective fields but are not considered intelligent in the traditional sense. Gardner stated that those individuals were intelligent under the evidence of the multiple intelligences theory. Gardner (1993) understood that though many individuals were not intelligent under the realm of logical-mathematical intelligence or linguistic intelligence, they were intelligent under the realms of musical intelligence and bodily-kinesthetic intelligence respectively. Consequently, he subsequently developed multiple theories defining what constitutes intelligence.

2.1. Visual-Spatial Intelligence

- Visual-spatial intelligence is the capacity “to perceive the visual world accurately, to perform transformations and modifications upon one’s initial perceptions, and to be able to re-create aspects of one’s visual experience, even in the absence of relevant physical stimuli” (Gardner, 1993, p. 173). Many of those who are spatially intelligent excel in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) (Kell & Lubinshki, 2013). Researchers have proposed advancements in the determination and identification of those individuals with a proclivity towards spatial intelligence (Kell & Lubinshki, 2013). In response to the demand, the Center for Talented Youth at Johns Hopkins University developed a Spatial Test Battery to assess the spatial intelligence of individuals taken in conjunction with or in place of the SAT test for certain STEM programs (Stumpf, Mills, Brody, & Baxley, 2013). Most universities rely upon mathematical intelligence and verbal intelligence determined using the standardized testing administered to potential students. Spatially intelligent individuals are not recognized and given the same opportunities as their mathematically inclined counterparts despite showing the same aptitude for the STEM fields (Kell & Lubinshki, 2013).There are connections made within individuals’ brains known as “mental maps” (Hu, 2014). These maps are a collection of the spatial knowledge that they gain throughout their day (Hu, 2014). Individuals then utilize this gained knowledge when faced with similar situations. Other individuals may use a “mental rotation” or the ability to mentally perceive an object from another angle by envisioning the object rotating (Karolyi, 2013). Hu (2014) established this theory with the use of the cognitive trails, whereby individuals can develop their spatial intelligence. Interestingly, Gardner (1993) stated that the multiple intelligences could be taught and developed unlike traditional intelligence that is relatively stable throughout life.

2.2. Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence

- Individuals express bodily-kinesthetic intelligence when they utilize their bodies to express emotion, feelings, or ideas (Ekinci, 2014). Many physical activities and exercises aid in the learning process for those who are prone to or prefer this type of intelligence (Zobisch, Platine, & Swanson, 2015). Individuals who regularly participate in sports have significantly higher levels of bodily-kinesthetic intelligence (Ermis & Imamoglu, 2013).

2.3. Logical-Mathematical Intelligence

- Logical-mathematical intelligence refers to deductive reasoning and logical thought processes and is preferred by those who enjoy patterns that are either logical or numerical (Adcock, 2014; Ansari, Nikneshan, & Farzaneh, 2014). Males have higher logical-mathematical intelligence than their female counterparts (Piaw & Don, 2013). Computer programming and chess are activities that people with elevated levels of logical-mathematical intelligence excel (Hafidi & Bensebaa, 2014). Researchers have indicated that there is a correlation between playing music and increased mathematical scores on exams (Taylor & Rowe, 2012).

2.4. Verbal-Linguistic Intelligence

- Those who excel in languages and reading rate higher in the verbal-linguistic intelligence (Al Muhaidib, 2011). Those individuals employed as authors, lawyers, and religious leaders typically have higher levels of verbal-linguistic intelligence (Ansari et al., 2014). A person with high verbal-linguistic intelligence finds learning new languages to be easier than others without such proclivity (Fonseca- Mora, Toscano- Fuentes, & Wermke, 2011). Since nurses are required to write down virtually everything that they do in the course of a day and give a report to the next shift, it is imperative that they have a significant level of verbal-linguistic intelligence. Grammar correlates positively with increases in verbal-linguistic intelligence (Shahrokhi, Ketabi, & Dehnoo, 2013). Those who are considered “mathematically under-prepared” have a dominant intelligence of verbal-linguistic intelligence (Mamhot, Havranek, Mamhot, 2014, p.59). When teachers educated students using a verbal-linguistic approach, they found the student performed much better than those who received traditional teaching methods (Mamhot et al., 2014). This further solidifies the logic that when individuals receive education or training that fits their preferred multiple intelligences, they are better able to grasp the concepts and understand the materials. Females have significantly higher levels of verbal-linguistic intelligence than their male colleagues (Piaw & Don, 2013). Since the majority of nurses (90%) are female, a higher level of verbal-linguistic intelligence is of importance (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015).

2.5. Musical Intelligence

- Individuals inclined towards rhythm, tempo, and pitch reflect musical intelligence (Gardner, 1993). There is a correlation between music instruction and increases in traditional intelligence (Goopy, 2013). Researchers indicated that there is a “Mozart Effect” that allows for increased spatial abilities and mathematical aptitudes in students who briefly listened to music before or during testing sessions (Taylor & Rowe, 2012). Additionally, Ball (2011) found that the human brain cognitively processes the emotional content of a musical piece faster than semantic content. These findings could be due to the different areas of the brain utilized for musical intelligence processing.

2.6. Interpersonal Intelligence

- Interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences show enhancement as individual leaders gain more experience (Piaw & Don, 2013). Interpersonal intelligence is a noteworthy measure of quality leadership (Gale, 2012; Piaw & Don, 2013). Interpersonal intelligence directly relates to patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction surveys yielded reviews that are more positive when the caregivers focused on interpersonal-based care (Chang, Chen, & Lan, 2013). Higher levels of interpersonal intelligence are required to deliver interpersonal-based care. Nurses who exhibit assertive communication methods have greater patient satisfaction (Maheshwari & Kaur, 2015). Greater interpersonal intelligence is required to determine the appropriateness of the utilization of an assertive communication style. Nurses who completed interpersonal communication skills training had increased job satisfaction (Dehaghani, Akhormeh, & Mehrabi, 2012). Those in management positions who have negative interpersonal predispositions are more likely to display derailment potential and ultimately derail in their careers (Carson et al., 2012; Quast, Wohkittel, Center, Chung, & Vue, 2012). Researchers also reported an inverse relationship regarding negative interpersonal skill-sets and derailment (Carson et al., 2012). Individuals who displayed greater interpersonal skill-sets were less likely to experience derailment during their careers.

2.7. Intrapersonal Intelligence

- McFarlane (2011) defined intrapersonal intelligence as “the capacity to understand oneself, to appreciate one’s feelings, fears, and motivations” (p. 2). Those with higher degrees of intrapersonal intelligence are better able to recognize their personal feelings and comprehend how they affect their decision- making processes. Intrapersonal intelligence often plays a role for those in leadership positions since leaders must understand their personal feelings relative to the activities that are taking place around them. An increased risk of derailment is associated with lower intrapersonal intelligence (Quast et al., 2012). Lower levels of self- awareness and self-insight are a factor in derailed careers for leaders (Quast et al., 2012).

2.8. Naturalist Intelligence

- Naturalist intelligence is defined as “the ability to perceive, like, and understand the surrounding natural world” (Demirel, Dusukcan, & Olmez, 2012). Those who have a high naturalist intelligence have an appreciation for the nature that surrounds. This appreciation includes the ability to identify various species of animals. Those with naturalist intelligence not only admire nature but also admire the aspects of their environments that are not necessarily natural such as cars and architecture (Demirel et al., 2012).

2.9. Existential Intelligence

- From the years 1994 to 1995, Gardner went on sabbatical and pondered other intelligences that might possibly exist (Gardner, 2003). Critics questioned Gardner regarding his obvious omission of an intelligence related to religious experiences. Gardner considered the inclusion of such an intelligence under the realm of existential intelligence (Gardner, 2003). Gardner (2003) claimed that he had eight and a half intelligences that would render the existential intelligence to be half of an intelligence.

2.10. Emotional Intelligence

- Emotional intelligence encompasses interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences (Tucker, Sojka, Barone, & McCarthy, 2000). Emotional intelligence encompasses one’s ability to control their own feelings and understand themselves and their emotions while reacting to others appropriately. Emotional intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, and intrapersonal intelligence are the three types of intelligence not traditionally taught in educational environments (Tucker et al., 2000). Consequently, Hess and Bacigalupo (2014) suggested that the definitions of previous scholars for emotional intelligence is a proclivity toward the perception of emotions in one’s self and others, the ability to think and understand utilizing these emotions, and to regulate their emotions in a manner that promotes intellectual growth and relationship building. Being part of a team that works well together can increase the emotional intelligence of the individual members (Wallis & Kennedy, 2013). There is also a link between emotional intelligence and effective learning strategies (Hasanzadeh & Shahmohamadi, 2011). Since individuals, in their formal education, do not properly develop the intelligence considered emotional intelligence, some individuals struggle with everyday interactions that interrupt their work. Derailment refers to the interruptions in the workplace, demotions, or loss of job due to poor performance. Self-awareness, or emotional intelligence, may aid in keeping individuals from derailing (Martin & Gentry, 2011). Further, there is a negative correlation between higher levels of emotional intelligence and the perception of stress levels in individuals (Singh & Sharma, 2012). Similarly, the utilization of interactive coaching sessions can improve an individual’s overall emotional intelligence (David & Matu, 2013). John Montgomery indicated that there is a propensity for individuals to learn emotional intelligence unlike the relatively static traditional intelligence conveyed by the intelligence quotient (Hyams, 2011). Since leaders influence others, it is important that they have high levels of emotional intelligence including the five components comprised within self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills (Wilson & Mujtaba, 2007). Hutchinson and Hurley (2013) conducted a study to determine if there was a link between leadership, emotional intelligence, and workplace bullying. The authors concluded that the emotional intelligence of leaders within an organization could influence the effects of bullying within their ranks (Hutchinson & Hurley, 2013). Hutchinson and Hurley’s research is relevant to the healthcare fields because they addressed how emotional intelligence influences the dynamics of the nursing units. In subsequent studies conducted, researchers found that employees’ perceptions of the leadership’s emotional intelligence could predict turnover. Fewer employees reported the intention of leaving an organization when they perceived their leaders to have higher emotional intelligence (Mohammad, Chai, Aun, & Migin, 2014). Therefore, there is a significant positive correlation between emotional intelligence and job performance (O’Boyle, Humphrey, Pollack, Hawver, & Story, 2011).

3. Leadership and Followership

3.1. Leadership

- In the study of leadership, researchers seek to identify potential leaders as well as to find the contributing factors that enable a person to excel in this area (Gudmundsson & Southey, 2011). Personality is a strong indicator of the potential for successful leadership (Hogan, 2015). Leaders and followers have different interpretations of the world around them (Nelson, 2014). Researchers have sought to determine a correlation between leadership and multiple intelligences (Elyasi, Sohrabi, Taheri, & Ghasemi, 2012; Ghamrawi, 2013; Nordin, 2011). Few researchers have evaluated the spectrum of multiple intelligences against leadership success, and none has added followership to their metric. Scholars have not produced any studies that examine leadership, followership, and multiple intelligences within the same study. Gale (2012) suggested future studies include the comparison between managers and non-managers to determine if there is a correlation between various job functions and the multiple intelligences that each of the study subjects’ embraces.

3.2. Followership

- There is a relative interdependence between leadership and followership. Leadership essentially cannot exist without followership and vice versa (Kean & Haycock-Stuart, 2011). Followership is a necessary component in effective leadership (Tonkin, 2013). Hierarchy within organizations often forces individuals to be both a leader and a follower (Kean & Haycock-Stuart, 2011). Leaders are often required to report to those who have more authority than they while also leading their departments, divisions, or subsidiaries. We sought, in this study, to determine if there were differences between those in leadership and followership positions and the various intelligences within the field of nursing.

4. Methodology

- Quantitative studies permit researchers to determine if relationships exist between variables and generalize based on their findings (Asamoah, 2014). Data collected within quantitative studies are typically measures, counts, and quantities of information gathered based upon the concepts or theories outlined within the hypotheses (Castellan, 2010). The use of a quantitative research method was appropriate because of a desire to examine the relationship between multiple intelligences of leaders and non-leaders. A survey instrument was used to collect the data. Spearman’s correlation analysis aided in the determination of correlations and generalizability. Surveys typically collect numeric data from subjects for generalization to a larger population (Yilmaz, 2013). Survey Monkey collected the data through their site, and we analyzed the data after all the subjects completed their surveys. Spearman’s correlation coefficient, Mann- Whitney U, and Kruskal- Wallis K were calculated. The p-value was set to .05 to assess the significance of the test, but was later decreased to p< .007 for the second research question during the post hoc testing. The post hoc testing was conducted using Bonferroni’s correction to increase the stringency of the statistical analysis and to reduce the possibility of a type one error (Abdi, 2007). Based on the current literature on the relationship between multiple intelligences and leadership, we believed that nurses that are in leadership positions would rate higher on the intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligences. Researchers indicated that leaders in the field of nursing had elevated levels of emotional intelligence (Wilson, Paterson, & Kornman, 2013). Since the umbrella of emotional intelligence contains both intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligences, one could infer that nurse leaders would rate highly in these intelligences. We also predicted that most of the respondents would likely be female since 90% of registered nurses are female (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). Other predictions included that the majority of the subjects would be of Caucasian decent because only 28.4% of registered nurses are classified as “Black, Asian, or Latino” according to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015).

4.1. Research Questions

- The first research question focused on the relationship between leadership roles and the multiple intelligences of nurses. The second research question sought to determine the relationship between seven demographic variables and the seven multiple intelligences of nurses. To determine the relationship between the groups, we utilized the Multiple Intelligences Checklist (Kline & Saunders, 1998). Participation in the survey was limited to those nurses ages 18 to 64 residing within the United States who were registered to take surveys administered by Survey Monkey or their affiliates. The following research questions and hypotheses guided this quantitative study:RQ1: Does the position of a nurse in an organization explain differences in the use of multiple intelligences? H10: The position of a person in an organization does not explain differences in the use of multiple intelligences. H1A: The position of a person in an organization does explain differences in use of multiple intelligences. RQ2: What is the relationship between demographic variables and the seven multiple intelligences of nurses?H20: A nurse’s gender does not explain the use of multiple intelligences.H2A: A nurse’s gender explains the use of multiple intelligences. H30: A relationship does not exist between the age of participant nurse and the use of multiple intelligences.H3A: A relationship exists between the age of the participant and the seven multiple intelligences. H40: A relationship does not exist between the participant’s years of experience in the field of nursing and the seven multiple intelligences.H4A: A relationship exists between the participant’s years of experience in the field of nursing and the seven multiple intelligences. H50: A relationship does not exist between the participant’s years of managerial experience and the seven multiple intelligences.H5A: A relationship exists between the participant’s years of managerial experience and the seven multiple intelligences. H60: A relationship does not exist between the participant’s years of general workforce experience and the seven multiple intelligences.H6A: A relationship exists between the participant’s years of general workforce experience and the seven multiple intelligences. H70: A nurse’s ethnicity does not explain differences in the use of multiple intelligences.H7A: A nurse’s ethnicity does explain differences in the use of multiple intelligences. H80: A nurse’s educational attainment does not explain the differences in the use of multiple intelligences.H8A: A nurse’s educational attainment does explain the differences in the use of multiple intelligences.The independent variables were the positions that the subjects held within their organization and the demographic variables. The subjects listed as having leadership positions were those who responded to the survey indicating they held a management position in their current organization. Those listed as having non-leadership positions indicated they worked within the general workforce in their present position. The demographic variables included gender, age, years of nursing experience, years of managerial experience, years in the general workforce, ethnicity, and educational attainment of the participants. The Multiple Intelligences Checklist (Kline & Saunders, 1998), was the instrument utilized to aid in the collection of data. Permission to use the instrument was obtained from both authors. Survey Monkey’s website hosted the 77-question survey along with demographic questions.

4.2. Design

- A non-experimental design was selected for this study. We sought to determine differences between groups and correlations between variables for this study. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal- Wallis tests aided in the determination of differences between groups. Spearman’s correlational coefficient assisted in the determination of correlations between variables. Correlational studies are quantitative research “in which two or more quantitative variables from the same group of subjects are taken through series of computations to determine if there is a relationship (or covariance) between variables (a similarity between them, but not a difference between their means)” (Asamoah, 2014, pp 45-46).Leaders and non-leaders were surveyed to determine their preferred multiple intelligences and help in answering the research questions. Additionally, each of the research subjects provided basic, non-identifying demographic information (i.e. age group, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, and job function) at the beginning of the survey. The independent variables were the employee’s status as being in a leadership position or a followership position. The respective self- reporting of holding a management position within their current organization aided in the inclusion the subject amongst the leadership group. The respective self- reporting of holding a general workforce position within their current organization assisted in the classification of the subject amongst the followership group. The dependent variables were the multiple intelligences of each of the nurses that volunteered as subjects in this study. The multiple intelligences included those defined by Gardner (1993) including logical-mathematical, visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, verbal-linguistic. Each subject completed the checklist. Scoring of the checklists was conducted according to the instructions included by the authors. The subjects were then compared to others within their field in leadership and non-leadership positions to determine the relationship between leadership and non-leadership roles and the intrinsic multiple intelligences of nurses.

4.3. Population and Sample Selection

- The total population for this study was the number of registered nurses within the United States, which is 2.8 million (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). The target population consisted of leaders and employees in non-leadership positions within the field of nursing who were signed up to take surveys with Survey Monkey or its affiliate websites. The total accessible population through Fulcrum Exchange (the affiliate of Survey Monkey utilzed for this study) is estimated at 29,000. The chosen method of data collection excluded all nurses who were not signed up with Survey Monkey and its affiliates. We used G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007), to determine the sample size. We also used an alpha (α) of .05 signifying that we desired to be 95% confident of not making a Type I error (Faul et al., 2007). The G*Power analysis indicated a sample size of 379 was needed to achieve statistical significance and identify a small to moderate effect size (r) of .18.The sample population was a convenience sample because of the host company’s available population. All subjects were nurses ages 18 to 64 living in the United States who were signed up to take surveys with Survey Monkey or its affiliated websites. A total of 389 survey results were received. Eight surveys were removed due to incomplete information or not meeting the criteria. After the exclusion of ineligible participants, the sample size used in this study was 381. Classification of the subjects as leaders or followers was dependent upon their self- reported status on their surveys. Leaders were those who reported that they worked in a management position within their current organization. Followers were those who self- reported working within the general workforce.The use of human subjects in research requires the consideration of ethical concerns by the IRB committee. The researchers consulted with the IRB committee to ensure protection of the participants. We protected the anonymity of the subjects by not collecting identifying information such as names, addresses, employer names, or social security numbers. The participants were given a disclaimer at the beginning of the survey that stated that participation was voluntary and they had the right to discontinue the survey at any time without penalty. Each participant had to click on the link to access the survey indicating their acceptance of the disclaimer and willing participation in the survey.

4.4. Instrumentation

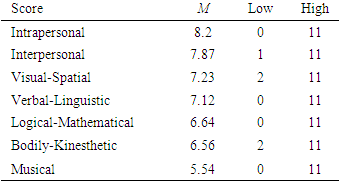

- Prior to taking the survey, subjects answered basic demographic questions including those related to their age range, gender, ethnicity, educational level, the length of employment within nursing, years of general workforce experience, and the number of years in a management position. The Multiple Intelligences Checklist instrument was utilized for this study. The survey requested the participants answer “A” if the statement applied to them and “B” if it did not apply. The 77 items aligned with the seven multiple intelligences: visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, musical, verbal-linguistic, and logical- mathematical intelligences. Each participant received a score from 0-11 for the number of items that they indicated applied to them for each of the seven intelligences. The numbers designated the sums of each “A” answer given for each of the said intelligences. A zero (0) was assigned for each answer of “B” and a half (.5) was assigned for all blank answers since blanks were neither yes nor no. Once each subject had a number assigned for each of the seven intelligences, the data was assembled into a spreadsheet and divided into two groups: management and employees. We noted the numbers one through seven in the margin and repeated until all seventy- seven items were labeled. Once appropriately labeled, the scorer counted the quantities of each numeric value and assigned the appropriate intelligence to each. The number one explained the visual-spatial intelligence. The number two connoted the bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. The number three signified the interpersonal intelligence. Intrapersonal intelligence was connotated with the number four. The number five signified musical intelligence. The number six indicated verbal-linguistic intelligence. The number seven denoted logical-mathematical intelligence. A tally kept the scores for each intelligence and aided the researchers in determining the subjects’ preferences. The subjects’ leadership or non-leadership roles determined the division of the groups. The researchers sought to determine if there was any relationship between the leadership and non-leadership functions and the intrinsic multipleintelligences.

4.5. Validity

- Research free from bias is deemed to have high internal validity (Higgins et al., 2011). The utilization of random selection enables researchers to minimize internal threats to validity. Threats to external validity typically arise when the researcher compromises the applicability of the data and over- generalizes it to realms not addressed by the study (Higgins et al., 2011). “Internal consistency describes the extent to which all the items on a test measure the same concept or construct and hence it is connected to the inter-relatedness of the items within the test” (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011, p53). The opinions of trained judges are the basis for content validity (Litwin, 1995). Researchers found that the instrument yielded valid results (Gale, 2012; Wilson, 2004). Gale (2012) stated that the Multiple Intelligences Checklist has “patterns of similar repetitiveness that measure the same factor” (p. 46). Previous researchers have also conducted pre-and post -tests to determine if the wording of the instrument was easily understood (Wilson, 2004). Wells (1999) explained that while internal and external validity are two different issues, the two types of validity are interrelated in that if the internal validity of the research is compromised, the results will not be generalizable to the population and even if the level of internal validity is high, the data is not worthy if it cannot be applied to a population. We utilized a G*Power analysis to determine that a sample size of 379 was needed for this study to achieve the desired small to moderate effect size.

4.6. Reliability

- The instrument has an internal consistency reliability because all the items within the survey meant to analyze specific characteristics yield comparable results. Other researchers that utilized the instrument all reported reliable results (Gale, 2012; Wilson, 2007; Wilson & Mujtaba, 2007, 2010). Standardization occurred by administering the survey in the same manner to each of the subjects. We found no previously published Cronbach’s Alpha for this instrument. After the data analysis, a Cronbach’s Alpha was performed, and the instrument yielded a .881 overall score which indicates a reliable instrument (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

4.7. Descriptive Data

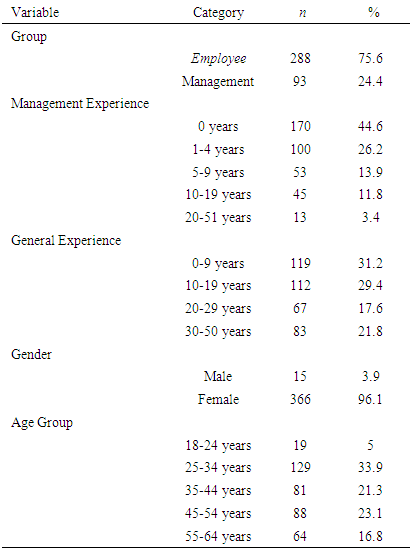

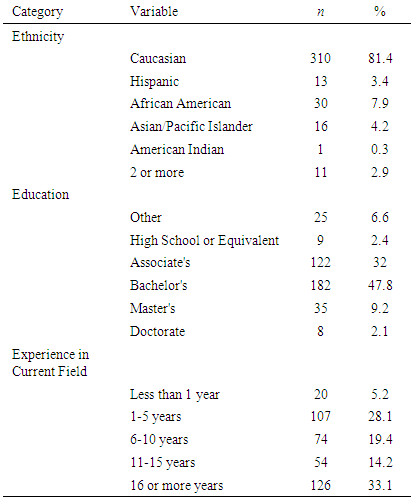

- Classifications of participants included management personnel (24.4%, n = 93) and employees in the general workforce (75.6%, n = 288). Almost half (44.6%) reported they had zero years of management experience. Almost sixty-nine percent (68.8%) of the participants reported working for ten or more years within the general labor force. Female gender comprised the majority of participants (96.1%). Over half the participants were between 25 and 44 (Table 1).

|

|

|

5. Data Analysis

- Three steps were used to analyze the data: (a) Test of Survey Reliability, (b) Test of Normality, and (c) Test of Association.

5.1. Test of Survey Reliability

- As described above, the Multiple Intelligences Checklist has shown to be reliable across different studies (Gale, 2012, Wilson, 2007; Wilson & Mujtaba, 2007, 2010). To confirm the instrument’s validity, a test of the survey reliability was performed. An overall Cronbach’s Alpha of .881 was calculated. A value of .70 or higher is considered acceptable (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Three intelligence scales, interpersonal (.708), musical (.789), and logical-mathematical (.711), each had acceptable values for individual intelligence according to the Cronbach’s alpha (α > .70).The remaining intelligence scales visual-spatial (.543), bodily-kinesthetic (.535), intrapersonal (.591), and verbal-linguistic (.562) had the minimally acceptable values (α between .50 and .70) (Gliem & Gliem, 2003). The lower levels of reliability for the latter intelligences may increase the risk of Type II errors in the findings.

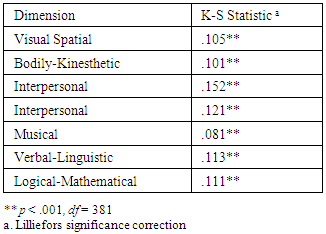

5.2. Test of Normality

- Each intelligence dimension was tested for normality. It is not uncommon for count data to follow a non-normal distribution (Lynch, Thorson, & Shelton, 2014). To confirm this premise, a K-S test of normality was performed on each dimension. For each dimension, the implied null hypothesis that the distribution was not normal could not be rejected, thus, nonparametric tests were needed to test the hypotheses. (Table 4).

|

5.3. Test of Association

- Research question 1 and research question 2 required different tests to be performed to reject the null hypotheses. Research question 1 required that an M-W test be conducted to determine if differences in means for each dimension by job category could be attributed to randomness. Research Question 2 required either an M-W test, a K-W test, or a Spearman’s correlation coefficient to be performed for each of the variables.

6. Results

6.1. Research Question 1

- The first research question focused on the difference in multiple intelligence scores based on the position of the participant. For this hypothesis, an M-W test was conducted to compare two groups, leader and follower, with each of the seven intelligence scale scores. Each of the seven intelligences had higher mean ranks for the management group when compared to the general workforce; however, only five of the seven differences were statistically significant. Visual-Spatial. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that visual-spatial intelligence was significantly different based on work group of management or employee. The output from the M-W test included the U statistic, Wilcoxon’s statistic, and the associated z score. The effect size r was determined by dividing the z value by the square root of the number of participants (r = z/ √N). The results of the test were not significant (z = -1.196, p = .232, r = -.06). The follower group had a mean rank of 187.20, while the leader group had a mean rank of 202.76. Bodily-Kinesthetic. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that bodily-kinesthetic intelligence was significantly different based on the work group of management or employee. The results of the test were significant (Z = -2.433, p = .015, r = 0.125). The results represent a small effect size (Cohen, 1992). The follower group had a mean rank of 183.27, while the leader group had a mean rank of 214.94.. Interpersonal. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that interpersonal intelligence was significantly different based on the work group of management or the general workforce. The results of the test were significant (Z = -3.123, p = .002, r =.160). The results represent a small effect size (Cohen, 1992). The follower group had a mean rank of 181.08, while the leader group had a mean rank of 221.73.Intrapersonal. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that intrapersonal intelligence was significantly different based on the work group. The results of the test were significant (Z = -3.179, p = .001, r =.163). The results represent a small effect size (Cohen, 1992). The follower group had a mean rank of 180.92, while the leader group had a mean rank of 222.23. Musical. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that visual-spatial intelligence was significantly different based on the work group. The results of the test were not significant (Z = -1.728, p = .084, r =.089). The results represent a small effect size (Cohen, 1992). The follower group had a mean rank of 185.48, while the leader group had a mean rank of 208.09. Verbal-Linguistic. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that verbal-linguistic intelligence was significantly different based on the work group. The results of the test were significant (Z = -4.282, p = .001, r =.219). The results represent a small to medium effect size (Cohen, 1992). The follower group had a mean rank of 177.39, while the leader group had a mean rank of 233.15. Logical-Mathematical. An M-W U test was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that logical-mathematical intelligence was significantly different based on the work group. The results of the test were not significant (Z = -3.935, p = .001, r =.202). The results represent a small to medium effect size (Cohen, 1992). The follower group had a mean rank of 178.45, while the leader group had a mean rank of 229.86. This combination of findings provides support for the partial rejection of the first null hypothesis (H10) for five of the seven intelligences.

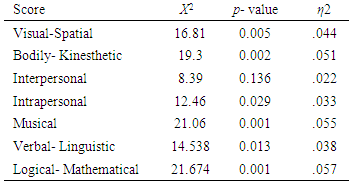

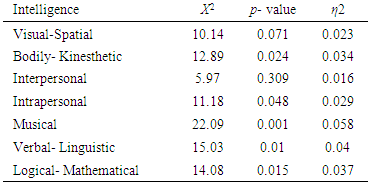

6.2. Research Question 2

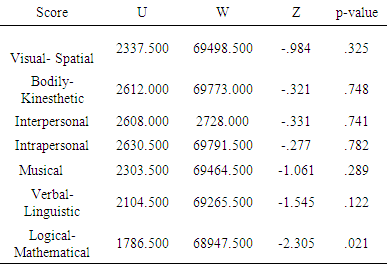

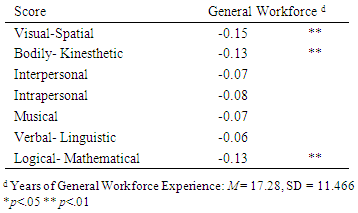

- The second research question focused on the relationship between the seven demographic variables and the seven multiple intelligences of nurses. The K-W test, M-W test, and Spearman Rank-Order Coefficient (rs) were used to test the null hypotheses. The K-W test was conducted to examine the relationship between ethnicity and education and each of the seven multiple intelligences. The M-W test was performed to examine the relationship between gender and the multiple intelligences. The Spearman Rank-Order Coefficient was determined to evaluate the relationship between age, years of experience as a nurse, years of management experience, and years in the general workforce and the seven multiple intelligences. As discussed above, the researchers used a p-value of < .007 to reject the null hypothesis in each test. Gender and Multiple Intelligences. Table 5 shows the M-W test conducted to evaluate differences in the associated intelligences between genders. Only the logical-mathematical intelligence showed a statistically significant relationship with the gender of the participants (Z (381) = -2.305, p = .021, r = .118), but did not yield significant results (p = .021) when the Bonferroni correction was applied to reduce the critical value to .007. All other intelligences showed small, non-significant relationships. The null hypothesis H20 was not rejected due to the lack of significant relationship when the Bonferroni correction was applied between any of the seven intelligences and the demographic variable of gender.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

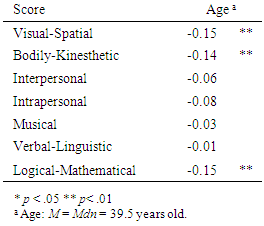

7. Summary of the Study

- Our findings were consistent with those reported by Wilson and Mujtaba (2010). The conclusions drawn support the previously reported results of Wilson and Mujtaba (2010) for the interpersonal and linguistic intelligences. Wilson and Mujtaba (2010) found no statistically significant correlations between the interpersonal and linguistic intelligences and age. Ekici, Sari, Soyer, and Colakoglu (2011) found no significant correlation between gender and verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal intelligences. Our study also found no statistically significant relationships between the previously mentioned intelligences and gender. Piaw and Don (2013) reported that males have a higher affinity for the logical-mathematical intelligence than do females. These findings from Piaw and Don (2013) are consistent with the findings of this study. While no statistically significant differences were found between logical-mathematical intelligence and gender, our findings indicated a higher affinity for males relative to their female counterparts. The results of our study stand in contrast to some of the findings of Wilson and Mujtaba (2010). Wilson and Mujtaba (2010) reported a statistically significant relationship between the intrapersonal intelligence and the age of the participants with a p- value of .026. Our study found no such relationship with a p-value of .136 and r of -.08. Intrapersonal intelligence and age had a non-significant negative association within the current study. Notably, the findings of our study add to the significance of multiple intelligences and leadership research. With a better understanding of the variables contributing to the composition of a great leader, human resources departments are better able to select the best candidates for leadership positions. The comprehension of followership in relation to leadership aids in the creation of teams that function well together. Conclusions drawn from our research suggested that those employed in a position of management self- report their individual intelligence higher than their counterparts employed in the general workforce. The demographic variables of age, race, and years of management experience showed statistically significant associations with several of the intelligences. These relationships indicate that ethnicity of the nurses has the statistically significant relationships with four of the seven intelligences to a p< .007 level after the adjustment of the critical value during the post hoc Bonferroni calculation. Our results also show statistically significant negative associations between age and the intelligences of visual-spatial (rs = -.15, p = .003) and logical-mathematical (rs= -.15, p = .004). These relationships could be explained by the aging process and the ramifications of aging on the human body including reduced cognitive functioning.

8. Implications

8.1. Theoretical Implications

- The theoretical implications of the results of our study included further examination of the intelligences as they relate to the various races of people. Our findings included a statistically significant association of four of the seven of the intelligences with the reported ethnicity of the participants. The findings should be further explored to determine if there is a theoretical implication that may warrant the inclusion of this caveat within the theory. Our results yielded a weak association between each of the statistically significant results. This weak relationship shows the current state of events relative to the hiring process and multiple intelligences. The associations between leadership and the multiple intelligencesindicated that using the seven intelligences as a recruiting and advancement assessment may benefit the organization.While the selected population allowed for generalizability, it is necessary to point out that only 381 participants contributed to this study. The single encounter survey limited the drop-out rate which, in turn, increased the external validity. Other researchers that utilized the instrument, all reported reliable results (Gale, 2012; Wilson, 2007; Wilson & Mujtaba, 2007, 2010). We conducted a Cronbach’s Alpha at the conclusion of the data collection stage and determined the overall score to be .881 which is within the acceptable range (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Standardization occurred by administering the survey in the same manner to each of the subjects. Consequently, our results were both generalizable and reliable. The methodology used for this study allowed for the utilization of a survey instrument and generalizability that would not have been obtained with an alternative method. Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory framed this research with seminal work on the various intelligences of individuals based on the intrinsic qualities that they possess. Gardner first wrote of the seven intelligences including visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, musical, verbal-linguistic, and logical- mathematical. Gardner later added two more intelligences including existential and naturalist. Gardner had stringent criteria for the creation of an intelligence.The theory of leadership has deep roots in the social constructs of humanity that aid the person in the position of inspiring others to accomplish a specified task or undertaking (Peterlin, Dimovski, & Penger, 2013). There are multiple types of leadership including servant, transformational, and laissez-faire. Each of the types of leadership has positive and negative traits that make them respectively more or less desirable to those who utilize them.

8.2. Practical Implications

- Human resource departments within a hospital setting, or any organizational setting, can use these findings to train their employees. Since these intelligences can be learned and enhanced, organizations can develop programs to train their employees on the use of the multiple intelligences desirable to their organization. Additionally, organizations can use multiple intelligences for better job assignment, team composition and patient-caregiver combinations once nurses are offered employment. Building functional teams of people who have similar intelligences or whose intelligences complement each other may be more efficient in achieving desired organizational goals. By building stronger teams that complement each other, leaders can function at a higher capacity thereby impacting the success of the organization.

8.3. Future Implications

- Our findings have many implications within human resources because those who are recruiting may wish to advance their knowledge surrounding multiple intelligence and how they apply it to the process. Future research will be impacted by the potential changes in recruiting methods as well. If human resource departments implement the new recruiting methods, stronger relationships will be likely.

9. Recommendations

9.1. Recommendations for Future Research

- The field of nursing as it relates to the multiple intelligences of leadership and followership needs further exploration to add to the knowledge. Due to the limitations imposed by the methodology chosen, we were only able to determine the numerical data from a self-reported survey. With the use of qualitative research, further information may be gathered that will add depth to the current study. One- on-one interviews may yield more information regarding the multiple intelligences of the participants than a survey can report as well as aid in eliminating some of the participants’ biases.Future researchers may wish to conduct a longitudinal study that evaluates subjects at various points in their careers to determine if their perceived multiple intelligences change or their propensity towards individual intelligences increases. Our research only examined nurses within the United States. Future researchers may conduct a quantitative study similar to this with leaders in other fields that have held their positions for a specified interval of time to determine if the duration of time in a management position alters the propensity to gravitate towards an individual intelligence. Future researchers may also wish to conduct a similar study within a single institution to compare the leadership to their respective followers to determine the relationship between leaders and the followers who personally work with them. Future researchers may also wish to conduct the same study with a more diverse population as this study had an 81.4% Caucasian population. Conducting a study on a more diverse group of individuals may yield more generalizable data.

9.2. Recommendations for Practice

- As previously stated, those in management positions who have negative interpersonal predispositions are more likely to display derailment potential and ultimately derail in their careers (Carson et al., 2012; Quast et al., 2012). Researchers reported an inverse relationship regarding negative interpersonal skill-sets and derailment (Carson et al., 2012). Individuals who displayed greater interpersonal skill-sets were less likely to experience derailment during their careers. Since it is imperative that leaders have strong interpersonal predispositions and intelligence, it is necessary for organizations to nurture this intelligence. The researchers derived the recommendations for practice from the results of this study.Ÿ Human resource departments can use this knowledge of multiple intelligences to assist them in the hiring process. With the examination of multiple intelligences, human resource professionals can ensure new personnel fit within the teams that they are placed. The entire population of the organization serves as a beneficiary of this recommendation since the staff hired will be more compatible with other team members and allow the organization to grow in the direction of their choice. Ÿ Leaders can use the multiple intelligences in their training to bring out the intelligences that they deem necessary for success within their culture and nurture those intelligences within their employees. Since the multiple intelligences can be developed unlike traditional intelligence, it is possible for organization leaders to train staff on the intelligences that they wish their employees to have. The facility and their individual employees serve as beneficiaries of this recommendation as each can grow together in a uniform direction that aids in the compatibility of the organization and staff. Ÿ Leaders can be selected from the pools of potential candidates within the organization with the use of multiple intelligence examinations and by nurturing those intelligences deemed relevant by the organization. The organization leaders and stakeholders benefit from this recommendation for practice because leaders can be organically cultivated from the ranks instead of spending more recruiting from outside of the organization.

10. Concluding Remarks

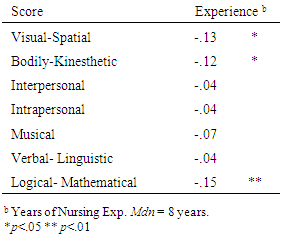

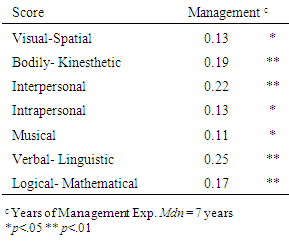

- Before conducting this research, it was unknown what relationship, if any, existed between leadership and the seven intelligences intrinsic to nurses within the United States. Our findings indicated the leadership position of the nurses as well as the years in the management position positively influenced their bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, verbal-linguistic, and logical-mathematical intelligences. While nurses in leadership positions had higher intrapersonal intelligence, the years in management positions did not increase this intelligence. Visual-spatial and logical-mathematical intelligences were found to decrease with age. Logical-mathematical intelligence was also found to decrease with the years of nursing experience while visual-spatial intelligence decreased with years of experience in the general workforce. This combination of findings is interrelated in that the decreases in visual-spatial and logical-mathematical intelligences across years of general workforce experience and years of nursing experience respectively may be attributed to both intelligences diminishing with age. Visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, and logical-mathematical intelligences vary across the various ethnic groups included within the study. Educational attainment may increase musical intelligence. This study added to the body of knowledge regarding multiple intelligences and established a statistically significant relationship between five of the seven intelligences and the leadership position held by nurses within the United States. Our study evaluated seven demographic variables and advanced the knowledge relative to the intelligences across the demographic spectrum. The findings will aid human resources and management personnel in the selection of appropriate applicants and advancement of suitable candidates.This study furthers the knowledge base relative to the multiple intelligences and their relationship with leadership and followership within the healthcare industry. With a greater understanding of the inner workings of the individual practitioner, the human resources departments within hospitals and healthcare facilities can compose better teams of workers who function at superior levels and give top quality care to their patients. Healthcare leaders should use all resources available to increase productivity, employee satisfaction, and patient outcomes. With the utilization of the multiple intelligences theory and the information gained from this study, those charged with hiring and advancement procedures will be better able to make sound decisions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML