-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2015; 5(2): 33-39

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20150502.02

The Effects of Demographic Attributes on Work Outcomes: A Study of the Lebanese Labor Market

Ali Sankari 1, Khalil Ghazzawi 2, Safwan El Danawi 3, Sam El Nemar 4

1Professor of Finance at the Lebanese University, Faculty of Business, Branch 3, Deputy Branch Manager at Lebanese Swiss Bank, Lebanon

2Professor of Management at the Lebanese University, Faculty of Law and Political Sciences, Branch 3, Lebanon

3Professor of Management at the Lebanese University, Faculty of Business, Branch 3, Chief of the Audit Department at Central Bank of Lebanon, Tripoli Branch, Lebanon

4School of Business, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

Correspondence to: Khalil Ghazzawi , Professor of Management at the Lebanese University, Faculty of Law and Political Sciences, Branch 3, Lebanon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper seeks to explore the relationships between demographic variables and work outcomes, specifically motivation, promotion, and work advancement. It also investigates the impact of demographics on sector preference, whether public or private. A conceptual model was developed based on a review of the literature. The model was tested through an empirical study involving a questionnaire collected from multiple respondents working in Lebanese companies. The results imply that demographic variables have a significant impact on work outcomes, some separately, and others jointly due to a multiplication factor. A deep analysis of the findings will be discussed in this paper. In order to understand the mentality of the Lebanese Employee, this paper will focus on the relationship between demographic variables and work outcomes. This paper fills a gap in the literature by providing empirical evidence about such relationships, as well as relevant implications that policymakers can utilize in making decisions that aim at raising performance and other work outcomes.

Keywords: Lebanese Workforce, Motivation, Work Commitment, Gender, Promotion, Private Sector, Public Sector

Cite this paper: Ali Sankari , Khalil Ghazzawi , Safwan El Danawi , Sam El Nemar , The Effects of Demographic Attributes on Work Outcomes: A Study of the Lebanese Labor Market, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 33-39. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Literature Review

- It is a common knowledge that demographic variables like age or gender may have some influence on work outcomes such as motivation, job commitment, career advancement, and even sector preferences. In general, education level represents the most important hiring criteria that applicants must satisfy to be assigned to a certain job. Also, there are promotions criteria, since measures of productivity within a job are necessarily restricted to workers who were assigned to a certain job and have not yet been promoted. For example, an empirical study [1] find that better educated workers need to achieve lower level of productivity before being promoted than do less well educated workers. Hence, even if productivity were positively correlated with education we could find that the better educated within a job are, on average, less productive than the less well educated workers.Older workers typically have more years of work experience than younger workers. Employees with more work experience generally earn more than workers with less experience. Thus, the age difference between private and public sector workers may indicate that public sector workers have more years of experience than private sector workers. In turn, a difference in work experience may be reflected in differences in earnings between private and public sector workers. [2]Workers with more education generally earn more than workers with less education. Other things being equal, the higher educational attainment of public sector workers, especially workers with an advanced or professional degree, likely affects the relative pay of private and public sector workers. [3]Due to the global work lab or force, the participation of women has increased dramatically over the past three decades, occurring in nations of varying levels of development [4]. Given the emerging global economy, understanding gender and cultural differences is critical to business success [5, 6]. Moreover, there are several management studies that examine gender differences in the workplace [7, 8] but underlying psychological explanations for these differences is not often the primary focus of gender research.Many theories discussed gender reproduction theory from an historical perspective and described gender as a socially constructed variable that is based on biological sex type [9]. While Gender systems, are historically rooted in inequality between men and women and comprised primarily of social practices [10]. Behavioral researchers have undertaken several strategies to discern disparities as they relate to the performance of working female and male adults in organizations. Their research on gender differences are generally associated with either culture value systems [11, 12] or personal attributes [13]. The findings from cultural studies indicate that males are more aggressive and competitive and less gentle, tender minded and concerned with home and family than females. The evolution/heredity explanation of a gender differences suggests that the key factors associated with them are attributed to different hormonal characteristics that occur as a result of evolution [14, 15]. These theorists believe different adaptive challenges throughout evolutionary history resulted in different responses by male and females to procreation, pregnancy, childbirth, childrearing, hunting, arousals needed to detect and avoid danger, and the like. Moreover, the social learning explanation of gender differences is based on social role theory [16]; the basis of this theory is a reciprocal interaction of the individual within the environment [17]. This psychological foundation holds that males and female are potentially alike. In fact, there are a lot of psychological characteristics that describe male and female behavior such as:According to heredity, that is transmitted genetically from generation to generation, illustrate that men and women vary with regard to motor differences, sexual/romantic attraction, and social dominance. First, Males have greater grip strength, throw velocity, throw distance, and sprint speed. Second, Males have less muscular flexibility especially boys have less ability to control their attention and impulses, and they demonstrate greater behavioral problems.According to Intelligence/aptitude, which is the ability to solve problems and comprehend potential to learn; male scores are equivalent for art, English language, and composition tests. Males score higher in math and science whereas boys score higher in science, spatial, and quantitative reasoning tests and lower in verbal and language tests. [18-20].Regarding the personality, the stable constellation of psychological characteristics that are unique to individuals, studies illustrate that men are more aggressive and place greater importance on taking the lead and controlling others. Moreover, males are less emotional (i.e. less anxious, less depressed, greater self-esteem, etc.); less agreeable, less warm/nurturing and less open to feelings [21-27].As far as the work interests, a stable constellation of psychological characteristics that are unique to individuals, it was illustrated that males are more assertive and open to ideas, they have a higher tolerance of risk, and males are less people-oriented and less tender-hearted. Furthermore, males score lower on social and conventional traits, however they score higher on realistic (i.e. mechanics, carpentry, etc.) and investigative traits. Furthermore, males are less people oriented and they demonstrate more interest in things, data, and ideas. [28-32].Regarding to live/work values, that is intrinsically desirable in life and at work, researchers had illustrated that males are more likely to value accomplishment and independence. Males are less likely to value friendship and equality, and they also place more importance on high salaries, taking risks, and organizational prestige. Males place less value on work satisfaction, respecting colleagues, clean working conditions, community and family, and friendships. Males devote less time to their careers [33, 34].On the other hand, there are gender differences in terms of preference sector, commitment, motivation, and advancement in Lebanese organizations.

2. Research Methodology

- In this study, a number of variables are considered along with the gender differences variables. Some of these are demographic (age, experience, marital status, kind of sector) and others are more job-related (motivation, advancement, commitment, and sector preferences). By considering these variables simultaneously, fake effects are minimized, and the most potent differences, by gender, are identified. A survey is developed that is about the gender differences in terms of motivation, advancement, and commitment in Lebanese organizations is developed and it is composed of 17 questions which 12 are questions related to motivation, advancement, commitment, and sector preference and the other 5 questions related to respondent’s profile.Therefore, participants are asked to respond to Likert scale items ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.For the next phase of the project, 25 organizations were randomly selected from different cities in Lebanon. Through intensive mail and telephone follow-up initiatives, 7 agreed to participate in the study. A total of 300 surveys were distributed to employees in several for-profit (financial services and insurance), Non For profit organization and public sectors.

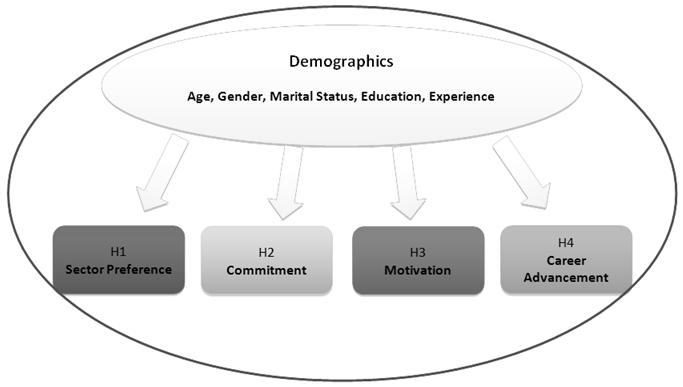

3. Research Model

| Figure |

4. Research Hypothesis

- - Sector PreferenceSector preference is used to define intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors [35] and consists of multiple measures representing several specific disciplines within the field of psychological measurement [36, 37]. It is used to help working adults make informed academic and career-related choices. Sector preferences also influence career choice decisions [38] and may shed light on the person-to-work environment fit.H1: Demographic variables may significantly affect the sector preference of employees.- Job CommitmentJob commitment may be defined as “one’s attitude towards one’s profession or vocation” [39]. In essence, career commitment involves the development of personal career goals and an identification with and involvement with those goals [40]. Employees who are willing to exert energy and be determined in pursuing personal career goals may be considered to have high levels of career commitment. At the core of the attitudinal approach, the individual is portrayed as having three dimensions of commitment: a belief in the organization’s mission, a desire to remain with the organization, and a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization.H2: Demographic variables may significantly affect organizational commitment.- MotivationThe profile of motivation captures the relative strength of employee’s achievement, affiliation, and power motivation. McClelland (1990) has performed extensive research on motivation related to behavior in managers. Each individual has, to varying degrees, needs for achievement, power, and affiliation. The need for achievement is defined as the desire to do better than others or to solve problems and to master difficult tasks more effectively. The need for affiliation is the desire to establish hand maintain close unfriendly relationships with other people. The need for power is defined as the desire controls other people, to influence their behavior or to be responsible for other people and their work.H3: Demographic variables may significantly affect employee motivation.- Career AdvancementCareer advancement defined as a pattern of work experiences spanning the course of a person’s life and is usually perceived in terms of a series of stages reflecting the “passage” from one life phase to another [41]. In this respect, career scholars have studied career advancement in specific organizations, particularly the implications of organizational career paths for both the organization and the individual. Organizational career advancement is an objective assessment of an employee’s career movement, either via hierarchical advancement or horizontal mobility. An employee is considered to have a “consistent and fair opportunity either to move higher in the organizational hierarchy or to move to other functional areas within the firm to gain broad-based experience for developmental purposes”.Therefore, companies try to eliminate gender differences so that women can compete as equals; they typically encourage women to learn to survive in a male dominated environment by adopting more masculine attributes. [42, 43]H4: Demographic variables may significantly affect career advancement.

5. Analysis of Findings

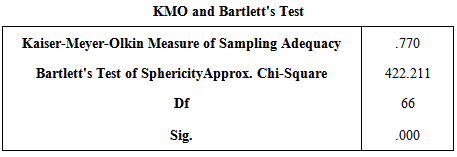

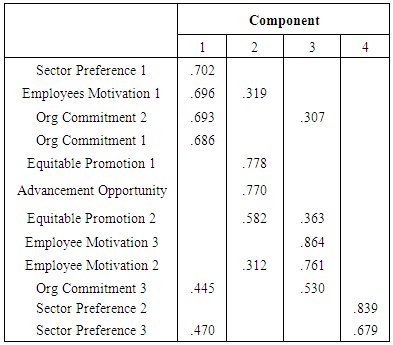

- - Sample AdequacyKaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) & Bartlett’s Spherecity test:KMO is used to assess the suitability of survey data for factor analysis [44]. As shown in table 2 below: KMO score had a value of 0.77 which is greater than 0.5, indicating that the data is suitable for factor analysis. Moreover, Bartlett’s test, which tells whether the variables are correlated in the population, revealed a significance value of .000. (p<.05)

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Interpretation of Results

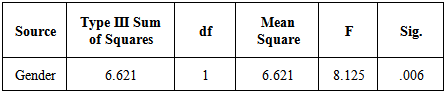

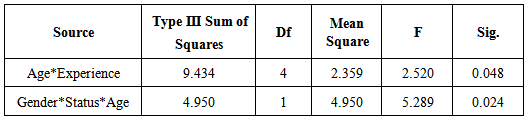

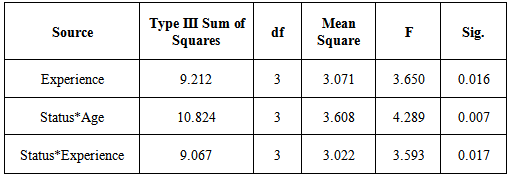

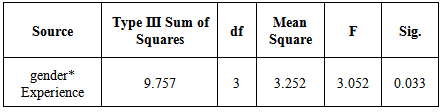

- Results show that sector preference is not affected by separate demographic variables. In fact, sector preference is significantly affected by the multiplication of gender and experience. This multiplication factor was the only factor that was highly significant in establishing an impact on sector preference (Sig. = 0.033).Furthermore, there seems to be a significant relationship between gender and organizational commitment (Sig. = 0.06). After comparing the means, we found out that women show more organizational commitment than men. This may be understandable since women seek security on the job, and are more willing to stick with their company than men are.In addition, it is commonly believed that gender has an effect on employee promotion. Promotion is decided mainly based on age, with some adjustments given for education level. Our results are different with this belief. Our results contrast sharply with the results of many previous studies which report substantial gender promotion gap within US and UK.This study shows that gender does affect the motivation process. However, through our data analysis the results showed that the multiplication of age and experience has a significant effect on promotion. Employees who are still young are motivated and do not see that promotion is easily available to them. However, older employees with more experience see that promotion is available to them. So we can conclude that age and experience are positively related to promotion in the Lebanese workplace.

7. Conclusions, Implication

- - ConclusionsThis research objective was to find out if demographic variables had an impact on work outcomes. Using ANOVA procedure, four variable factors were chosen to test for any difference in gender in case of organizational commitment, promotion, motivation, and economy sector. It is generally perceived that there is no significant difference between men and women in the work field, since women nowadays are being treated as equals. However the majority of employers still have stereotypical beliefs that men are more qualified at their jobs than women. Our results have generated new results that connect demographic variables to certain work outcomes, separately in some cases, and jointly in other cases.- Implications1. Since males showed less organizational commitment than females, companies should adopt retention strategies that enhance the organizational commitment for males, such as engaging them in activities that would raise their feeling of belonging to the company, and targeting them for development opportunities and empowerment initiatives.2. Since younger and inexperienced employees do not believe that firms are providing satisfactory career advancement opportunities, it is important that firms clarify the career path for all new hires, and adhere to the career path in a consistent manner.3. Since experienced personnel show more motivation than inexperience done, it is important to assign complex and important tasks to experienced employees since they have the needed motivation to complete them successfully. As for inexperienced personnel, it is important to adopt strategies that would raise their motivation level, through the proper incentives.4. Since experienced females have a preference and commitment to the private sector, this means that the private sector will benefit from low turnover rates and quality experienced personnel. This means that human resources in the private sector are stable and rich in quality. So the private sector should maintain current practices to retain those valuable human resources.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML