-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2015; 5(2): 27-32

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20150502.01

Academic Burnout and the Positive/Negative Spillover from Non-Academic to Academic Activities in University Students

Takashi Tsubakita 1, Kazuyo Shimazaki 2

1Faculty of Communication, Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Aichi, Japan

2Department of Nursing, College of Life and Health Sciences, Chubu University, Aichi, Japan

Correspondence to: Takashi Tsubakita , Faculty of Communication, Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Aichi, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study evaluated the influence of students’ multiple roles on academic burnout and clarified how students’ time spent in non-academic activities moderated the relationship between perceptions of spillover and academic burnout. We asked students about perceptions of positive and negative spillover from non-academic to academic activities, academic burnout, and time consumption on part-time job(s), club, and other student activities. Data from 2,719 undergraduate students from five universities in Japan were analyzed. We tested a hypothetical model demonstrating the relationship among positive and negative spillover, burnout, and time spent in non-academic activities. The perception of negative spillover from non-academic activities to academic activities reinforced the students’ burnout (p < .01), whereas the perception of positive spillover alleviated the burnout (p < .01). Fit of the hypothetical model to the data met the respective criteria. Multi-group analysis indicated that the magnitude of negative spillover was stronger than positive spillover in groups engaged in non-academic activities for more than 12 hours. The influence of multiple roles on students’ burnout depends on how they evaluate their non-academic activity. Perception of positive spillover alleviated academic burnout and negative spillover worsened burnout, but the impact of spillover was moderated by amount of time spent in non-academic activities.

Keywords: Academic burnout, Positive and negative spillover, Academic and non-academic activities, Multiple roles

Cite this paper: Takashi Tsubakita , Kazuyo Shimazaki , Academic Burnout and the Positive/Negative Spillover from Non-Academic to Academic Activities in University Students, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 27-32. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20150502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

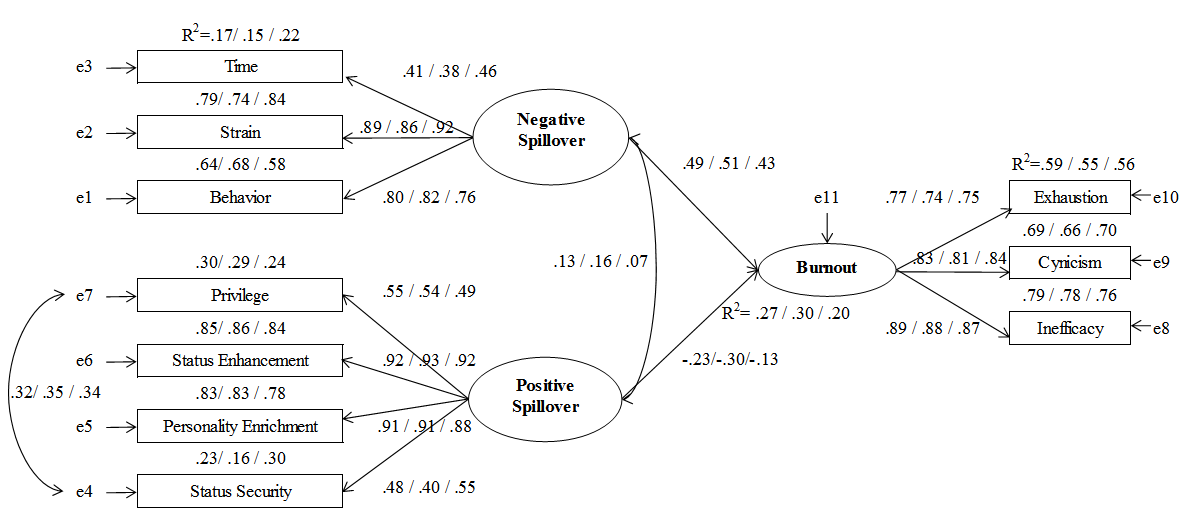

- In Japan, an extended structural recession since the 1990s has been economically suppressing university students’ lives [1]. However, financial pressure on students is not necessarily a negative impact for Students. In the United States, for example, numerous studies on the effects of part-time jobs on academic performance and students’ lives have been conducted [2, 3]. Reviewing studies conducted up to 1981, Hammes and Haller (1983) pointed out that working up to 20 hours per week had no negative impact on students’ grade point averages. They emphasized the positive effects of students’ job participation on college life and on their growth as individuals. Several nationwide studies in Japan suggested that most traditional students in Japan have some kind of part-time job, and the influences of their job experiences on their academic activities seem to be ambivalent [1, 4, 5]. Besides part-time jobs, most university students may engage in various kinds of club activities and circles. These non-academic activities are also considered to have both positive and negative influences on academic activities.The idea that non-academic activities pertaining to multiple roles rob students of time and energy to engage in academic activities is quite conceivable. This line of thought has been recognized as the “scarcity hypothesis” [6–8]. Specifically, Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) regarded time-based conflicts, strain-based conflicts, and behavior-based conflicts as the three major interdomain conflicts to explain nonwork-to-work negative spillover in employed workers [9, 10]. The assumption here is that resources such as time and energy are limited, and if workers commit to non-work domains too much, they may suffer from role overload and interdomain conflict. Cushman and West (2006) investigated factors of student burnout and reported that 24% of 354 participants noted the “external factors that occur [sic] outside of the classroom…work, personal relationships (e.g., family and friends), financial difficulties, and time management” ([11], p. 26). These students suffered from multiple roles resulting in negative spilloverfrom “external factors” to academic performance, which led to academic burnout [12]. There may be, however, those students who experience positive spillover, or whose “external factors” do not negatively influence their academic performances. If work experiences positively influence one’s academic engagement, enhancement of one’s resources via multiple roles would be conceivable. As enhancement factors, Sieber (1974) suggested that benefits such as “role privileges,” “status security,” “status enhancement,” and “enrichment of the personality” are accumulated as benefits of multiple roles [13, 14]. In the case of students with part-time jobs, for example, difficulties and burdens pertaining to academic activities are buffered by part-time job experiences which provide various resources, such as money and social skills. In this sense, this suggests that resources that are used in a certain role can be invested in another role, enhancing one’s personality and self-concept [15]. These positive effects reinforce one’s well-being as a student, and as a result, motivation for academic activities is enhanced [16, 17]. According to Marks “Some roles may be performed without any net energy loss at all; they may even create energy for use in that role or other role performances” ([8], p. 926). The assumption is that resources other than time are unlimited or rechargeable. Hypothesis on Spillover from non-academic to academic activitiesAlthough the scarcity and enhancement hypotheses seem to be antinomic, those who perceive positive facets of non-academic activities might also recognize negative facets, and vice versa. Therefore, we hypothesized that the perception of positive spillover from non-academic activities to academic activities is correlated positively with the perception of negative spillover (Hypothesis 1). In the hypothetical model (figure 1), students’ perceptions of negative spillover affect perceptions of academic fatigue (measured as academic burnout) differently. Students may recognize unwanted effects of non-academic activities on academic activities, such as time deficits, fatigue, and anxiety. Therefore, we assumed that the perception of negative spillover worsens academic burnout (Hypothesis 2). On the other hand, non-academic activities may provide benefits such as useful information, skills, and study support, and these merits may reinforce the motivation and provide resources for learning [18]. Thus, we hypothesized that the perception of positive spillover alleviates academic burnout (Hypothesis 3). The words “academic activities” refer not only to lectures in class and study hall but also to test taking, lab experiments, and clinical practice. “Non-academic activities” included part-time jobs, club activities, and students’ committees of various kinds on and off campus.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- First, we secured agreements from the deans of targeted departments and the lecturers of targeted classes. To avoid bias associated with measuring students of one major at one university, undergraduate students (N = 3,431) from seven universities as well as students from nursing colleges in two major cities (Tokyo and Nagoya) and three rural area (central, west, and north Japan) were recruited. Of the 3,431 students approached, some students declined to answer the questionnaire or did not complete the questionnaire because, in a few classes, they only had a little time at the end of their lecture to do so. In addition, extreme outlier cases (e.g., cases with “0” in all items and cases showing significant Mahalanobis distance) were excluded, leaving a final sample of 2,719 responses (response rate was 79.2%; 1,535 male, 1,175 female, 9 unreported gender; mean age = 19.8, SD = 2.1). Student majors were biology, computer science, architecture, mechanical science, nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and clinical engineering.

2.2. Measures

- To assess positive and negative spillover, we constructed scales based on two questionnaires developed by Kirchmeyer (1992) [10], changing the words as appropriate for students (e.g., “work” was changed to “study”). The positive spillover scale was composed of four subscales: privileges gained from the non-academic activities (three items, e.g., “earns me certain rights and privileges that otherwise I could not enjoy”); status security (four items, e.g., “gives me support so I can face the difficulties of study”); status enhancement (four items, e.g., “gives me access to certain facts and information which can be used at work”); and personality enrichment (four items, e.g., “develops skills in me that are useful at work”). The negative spillover scale was composed of three subscales: time based (one item: “demands time from me that could be spent on my study”); strain based (four items, e.g., “produces tensions and anxieties that decrease my performance at class”); and behavior based (three items, e.g., “makes me behave in ways which are unacceptable at class”). Each item of these two scales begins with the phrase “my engagement in non-academic activities since the previous semester…” All items were scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 6 = “strongly agree.”To assess academic burnout, the MBI-SS1 was used [19–21]. This 15-item scale consists of three subscales: exhaustion (EX: five items, e.g., “I feel emotionally drained by my studies”); cynicism (CY: four items, e.g., “I have become less enthusiastic about my studies”); and inefficacy (IN: six items, e.g., “I can’t effectively solve the problems that arise in my studies”). All items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “never” to 6 = “always.” Original version of the MBI-SS consists of 16 items, but one item in cynicism is ambiguous for students. Therefore, we excluded the item from the questionnaire. In addition, unlike the most previous study which uses the un-reversed items as efficacy [22, 23], we used un-reversed items in the dimension of the inefficacy to assess literally meanings of the inefficacy [18].

2.3. Procedures

- Students were recruited in class by their instructors, who assured them (both verbally and in writing) that participation was voluntary, refusal to participate would in no way impact them negatively, and that they would remain anonymous. All participating universities were assured anonymity. The students completed the questionnaire during lectures. Those students who agreed to participate were asked to complete the questionnaire during the class, which required approximately 15 minutes. This research was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Chubu University (approval number 240048).

2.4. Analysis

- To evaluate the fit of the hypothesized model to the data, we adopted the following indices: (1) the χ2 statistic, (2) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) [24], and (3) the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) [25]. Values for CFI greater than .90 indicate acceptable model–data fit. For RMSEA, values less than .08 indicate a satisfactory fit, while those greater than .10 signify that the model should be rejected [26, 27]. Path analysis and subsequent multi-group analysis were implemented using AMOS 21.0.

3. Results

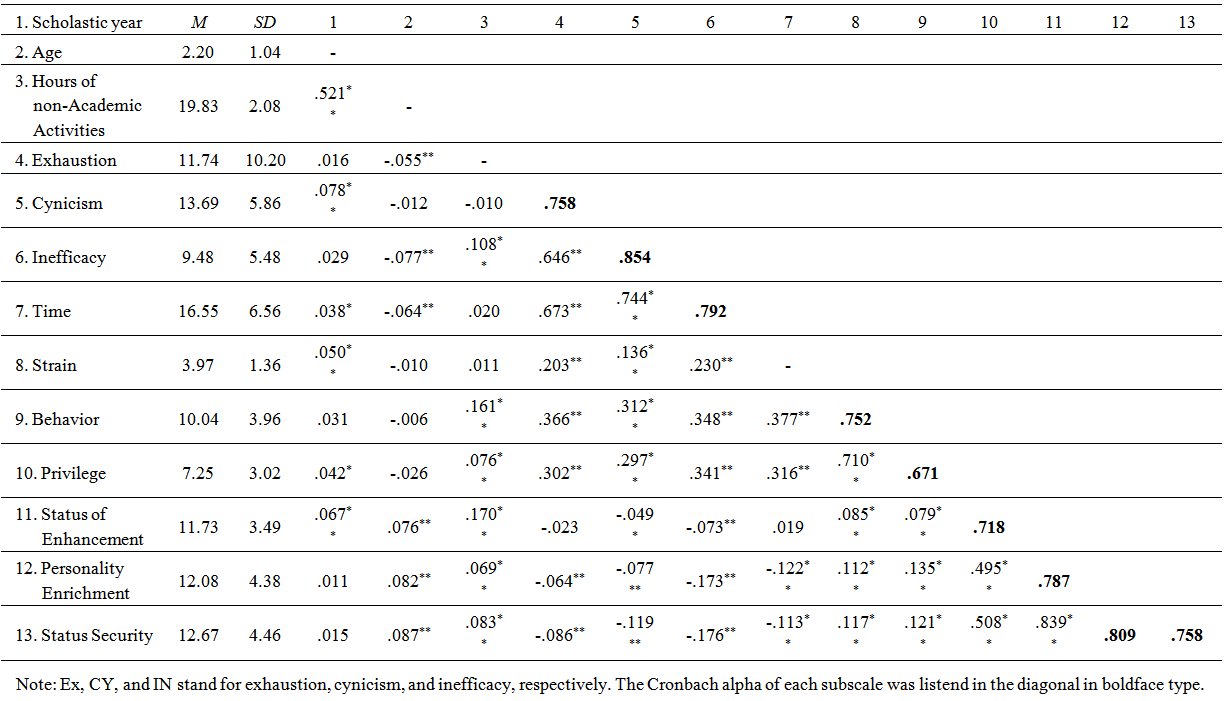

- Descriptive statistics for independent variables (age, engagement in non-academic activities, perceptions of negative and positive spillover) and dependent variables, as well as the internal consistency estimates of them are shown in Table 1. Generally, very weak but significant positive intercorrelations between subscales of Positive and Negative spillover were observed. In addition, there are weak but significant negative intercorrelations between subscales in Positive spillover and subscales in MBI-SS, respectively. It is worth noticing that there were no significant correlations between amount of time spent in non-academic activities and subscales of MBI-SS except Cynicism.To test all of the hypotheses concerning spillover effects and burnout, the hypothetical model was analysed, showing that the model was generally supported by the data (χ2 = 566.25, df = 31, n.s., CFI = .958, RMSEA = .080), when weadded additional paths between residual variables of privileges and status security (Figure 1). Negative spillover positivelyaffected burnout (Hypothesis 2), whereas positive spillover negatively affected burnout (Hypothesis 3). In this respect, academic burnout was influenced by students’ perception of spillover (R2 = .27). There was no statistical difference between the magnitude of Negative and Positive spillovers when we used all samples.

| Table 1. Correlation matrix of the age, engagement in non-academic activities, subscales of MBI-SS, and subscales of negative and positive spillover |

4. Discussion

- The present study focused on the perceptions of spillover effects of non-academic activities such as club participation and part-time jobs on students’ subjective academic fatigue measured as burnout. Although spillover effects of non-academic activities have both positive and negative sides, these facets are not at all antinomic. This assumption was represented by hypothesis 1. Students engaging in non-academic activities can generally recognize that their non-academic activities help as well as hinder their academic work. However, the correlation of positive and negative spillover was relatively low. Referring to Table 1, subscales of negative and positive spillover were mutually but only weakly positively and negatively correlated. A post hoc interview with a few participants suggested that the questionnaire on spillover was somewhat complex, although they recognized the positive and negative facets of non-academic activities. This could be one of the reasons for low intercorrelations. Another explanation could be that the responses to positive spillover contaminated the responses to negative spillover because of the cognitive tendency to avoid inconsistency. In any case, however, the experience and perception of spillover on both sides are important factors for students to maintain their work-life balance in academic life.Unlike non-traditional students [28], most traditional students are expected to exercise their own discretion in their activities. However, it is quite natural to consider that the amount of time spent in non-academic activities robs them of time for academic engagement to a greater or lesser degree. The R2 of “time constraints” in negative spillover was relatively small (.17), compared to other subscales. Therefore, subjective evaluation of time constraints can be explained by latent factors other than negative spillover. On the other hand, our data implicated that, as can be seen in Figure 1, the amount of time resources (an “objective” evaluation of time) seemed to be one of the important moderators between academic burnout and spillover effects. The magnitude of positive spillover becomes weaker compared to negative spillover when students spend considerable time in non-academic activities such as clubs and part-time jobs.Our results indicated students’ subjective evaluation of their multiple roles influenced students’ academic well-being. It is worth noting that our model does not suggest that students’ engagement in the non-academic activities perse was a direct factor of the burnout but that perceptions of their negative and positive facets influenced academic burnout. The result of the post hoc multi-group analysis also suggests that the amount of time spent engaging in non-academic activities was the moderator variable for the relationship between spillover effects and academic burnout.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

- Although the current study added important implications for students’ academic and non-academic balance, there are three limitations. First, this study was a cross-sectional design. Students’ perception of the spillover changes over the course of students’ life cycles and development. Therefore, longitudinal research is needed to confirm our results. Second, the study did not discuss positive psychological variables such as academic engagement [29, 30]. Subjective evaluation of engagement in academic activities would be an opposite state from burnout, but the relationships between positive spillover, negative spillover, academic engagement, and time consumption in non-academic domains were not evaluated. Third, the study lacks suggestions to reduce the negative spillover from non-academic activities to academic activities. To our knowledge, negative spillover and burnout are both related to personality aspects [31–34]. Linville, for example, considered self-complexity as a buffer against the adverse influence of stress, which causes illness and depression [35, 36]. The amount of time engaging in non-academic activities as a moderator may be interpreted differently if we take the personality variables into consideration.

Note

- 1. MBI-Student Survey-School and University forms (MBI-SS): Copyright ©2012 Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Michael P. Leiter, Christina Maslach& Susan E. Jackson. Note: MBI-SS is based on the MBI-General Survey (MBI-GS): Copyright ©1996 Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Michael P. Leiter, Christina Maslach& Susan E. Jackson. All rights reserved in all media. Published by Mind Garden, Inc., www.mindgarden.com

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML