-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2013; 3(4): 157-165

doi:10.5923/j.hrmr.20130304.04

Revenue Sharing Regimes and Conflict Prevention in Nigeria: Between Government and Private Sector?

Essien Akpanuko1, Anietie Efi2

1Department of Accounting, University of Uyo, P. M. B., 1017 Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

2Department of Business Management, University of Uyo, P. M. B. 1017 Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Essien Akpanuko, Department of Accounting, University of Uyo, P. M. B., 1017 Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Inequitable resource sharing in different countries and communities has been the bane of conflict. It has been the basis for violent conflict in Nigeria in general (Boko Haram) and in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria, in particular (Niger Delta Militants). This paper seeks to find out the factors that sustain these conflicts, to evaluate the way forward for peace and the stakeholders’. The Review of literature approach is adopted. From existing documented history and analysis of events, conflict and crises, the Nigerian case is a paradox of poverty and violent conflict in the midst of abundance. In the centre of this conflict and crises is an ‘unfair complex and inconsistent formula for the distribution of oil revenue only, while revenues from other resources are wholly owned by the region in which they are found. The Niger Delta region has suffered several years of neglect and environmental degradation from oil exploratory activities. The multinational companies’ operating in this region has not been helping matters, largely due to corruption. The conflict situation in the Niger Delta of Nigeria presents itself in diverse form but can be traced to the advent of oil and lack of a fair institutional framework of revenue distribution, where some exist, it is created to be breached and bedeviled with unscrupulous legislature that circumvent the true state of the “Cake Sharing” formulae. The paper presents a case for Strategic Government-Stakeholders-Private Partnership built on accountability.

Keywords: Conflict, Revenue, Resource sharing, Partnership, Equity and development

Cite this paper: Essien Akpanuko, Anietie Efi, Revenue Sharing Regimes and Conflict Prevention in Nigeria: Between Government and Private Sector?, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 157-165. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20130304.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In capturing the conflict situations in the world at large, Akpan[1] puts across the following questions;● Why do we have ethnic conflicts in different parts of the world at a time when there is tremendous growth in education and modernization?● What accounts for the intra-country civildisturbances?● Why do countries disintegrate?● How equitable are resources shared in different countries and communities?The last question – How equitable are resources shared in different countries and communities? – underscores the problem of conflict and if answered, provides solutions to other questions. But because it is hardly ever answered in the affirmative, conflicts – both violent and non-violent - exist. Conflict negates economic development, triggers ethnic tension and engenders loss of lives and properties; causing untold human suffering and wrecking havoc in socio-economic and environmental terms[1,5,22].These conflicts manifest in various forms, with ethnic and religious undertones, and are a result of failed governance [23] and poor corporate social responsibility of the private sector enterprises that reap the much benefits of peace[13]. While the responsibility of fostering peace and conflict prevention (CP) lies primarily with the government, other societal actors have a role to play, especially the private sector. Economic failure is closely linked to political failure initiated by ethnic crises that results from the desire to control a nation’s resources; and inequitable distribution of the resources is always the root cause of civil unrest[24].Can the private sector contribute to the prevention of these conflicts? Should the burden and responsibility of conflict prevention be that of government alone? The private sector (Companies) while having little or no influence over a given country’s economic policies and infrastructures, they nonetheless have great influence over the allocation of economic and financial resources as a result of their business operations[5,9,13,14,17,22]. Indeed in many countries around the world, poverty and inequality are not necessarily due to lack of resources but rather, lack of access to resources generated by the private sector.The Nigerian case is one of such and presents a paradox of poverty and inequality amidst plenty and varieties of sharing formula. Faced with multiple crises and violent conflict that manifests in different forms (religious, ethnic and marginalization, economic and political), the nation seek means of mutual existence in a heterogeneous society. These raise the question – What is an equitable means of sharing resources and how can it be achieved?To address this all in one problem, the paper is discussed in two sections;(a) Lessons from Nigeria conflict situations and revenue sharing regimes, (b) The strategy (not tried in Nigeria) – The how?

2. Lessons from Nigeria’s Revenue Sharing Regimes

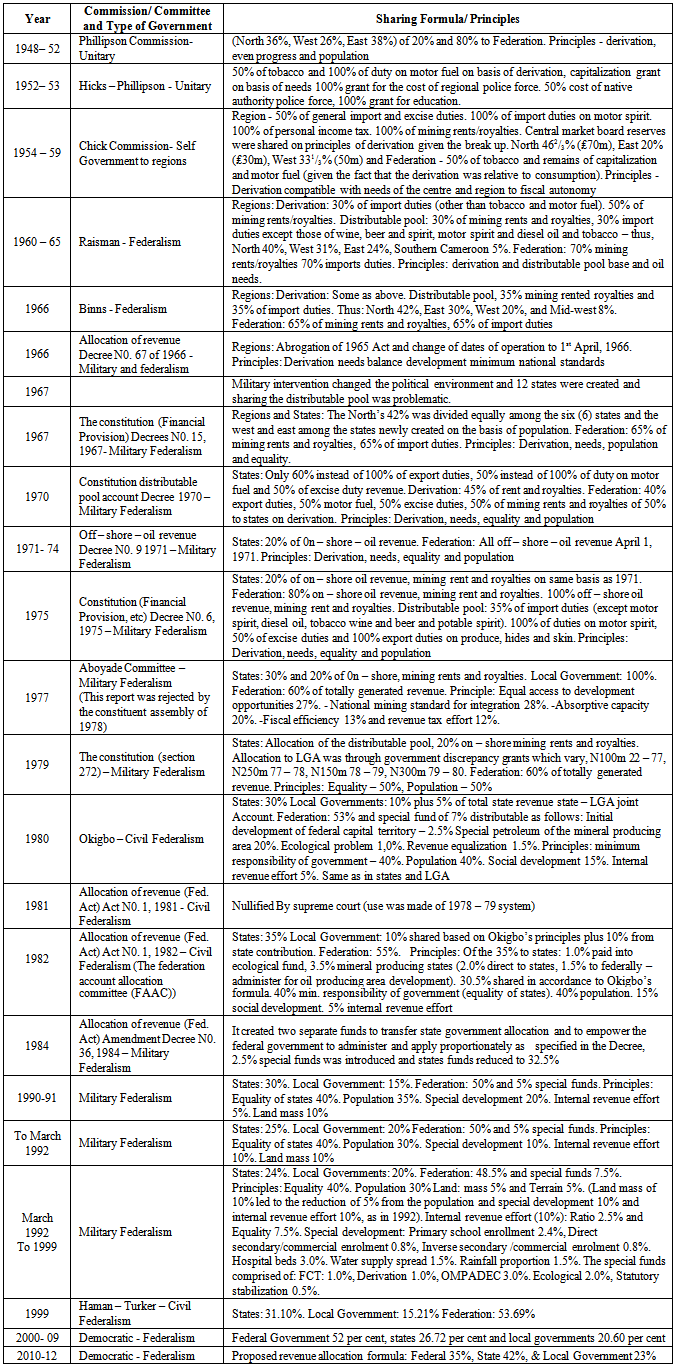

- Bequeathed with a contentious federal system by the United Kingdom at independence in 1960, the nation and over 250 ethnic groups are saddled a dysfunctional system of centralized ethno-distributive federalism, always engaged in frenzied competition to control the consumption of existing revenues. This competition has been noted as the major source of conflict (violent and non-violent) with ethnic, political and religious undertones[11,15,16,20,].Nigeria, a nation in chaos and on the brink[25], started out as four (4) region transformed by the need to resolve conflict into twelve (12) states in 1967, 19 states and 301 local governments in 1976, 21 states and 449 local governments in 1987, 30 states and 589 local government in 1991 and 36 states including Abuja and 774 local government area in 1996.To reduce the manifesting conflict progressively, several revenue allocation committee, commission and decrees were put in place to provide an equitable formula for sharing the national “cake” among the region and tiers; North, West, East, Midwest and Federal, States and Local government. The first being the Phillipson Commission of 1946 established by the colonial masters in their unitary system and three others before independence; Hick – Phillipson Commission of 1951, Chick and Raisman commission (1953) and Raisman commission of 1958. These commissions based their revenue sharing on derivation, 50% to the province area, 15% to the central government and 35% to others. After independence, the seed of ethno-resource conflict was formally sowed. The issue was left after the manner of the colonial masters. There was no formal agreement on the benefits of the federation to federating members; who gets what from whom and gives what to whom. Instead several commissions were established.Between 1960 and 1979, in nineteen (19) years, there were four different revenue sharing commissions; the Binns commission1964, Dinna commission 1968, Aboyade commission 1977 and Okigbo commission 1979. Between 1979 and 1994 many ad-hoc changes and amendments were introduced by the military. It is interesting to note that after the discovery of oil as a source of revenue in the south east, the principles of allocation changed from derivation to population, size and equality of states. Derivation was no longer an important issue and the inequality was deepened. To cover up for the inequitable sharing principles, more unsatisfied formulas were introduced, and states and local governments were created.Why the many unsatisfied conflict prone formula and number of states and local government? The answer is based on an understanding of the institutional design governing different sections which explains why some groups are more powerful than others[2,4]. The rules of the game (the politics) of national cake (resources) distribution are mostly honoured when breached and many individual actors circumvent institutional designs to enrich themselves and their constituencies[10]. Nigeria’s case presents the above.Before the 1970s there was relative peace, except only for the struggle for power, which necessitated the control of resources; power without resources does not last, thus things were changed to allow for both. By 1970 oil replaced agriculture as the major source of revenue. This changed the locational-directional flow of resources to centre. The oil producing area (minority states) becomes the oil Mecca of Nigeria. This brought developments and was taking away ‘resources power’ from those in power (the majority). To strip the minority of this resources power, Awolowo with the support of the majority Northern area, introduced the indigenization decree and a policy of onshore – offshore oil dichotomy. This allows 60% ownership of foreign companies to Nigerians. These companies were taken over by the west. The dichotomy gave total ownership of oil produced offshore to the centre and only 1 – ½% of royalty to producing states[16].The creation of twelve (12) states out of the four regions in 1967 increased the pressure for equitable allocation of revenue from national resources. As dissatisfaction in the revenue allocation mounts and to completely deny the minority (South-East) of any right to their resources, the land used decree of 1978 was enacted. This gave the central government, controlled by the North and West, ownership of every piece of land, which implies all the national resources. The change in the distribution principles from derivation to population, size and equality of states was justified in principle.This development gingered the request for creation of more states from the old regions to increase the share of revenue received from the distributable pool and more states were created. Before the creation of states, at the end of 1962 census exercise, Northern Nigeria was half a million less than the south and the result was rejected by Abubakar and the British representation, Warren was fired. The 1963 census was called for, which shows the “over counting” of the North by 8.5 million and Nigeria was 60.5 million (a figure believed to be too high and was scaled down to 55.66 million) and the North balloon to 31 million. With the protest of the south, the North was scaled down to 29.8 million while the East, South and Midwest remain as they were in 1962 census at 12.4 and 2.5 million. The west increased from 7.8 million in 1962 to 10.3 million in 1963. This result met violent protest but since the North and the West had their increases the protest was bounced. This led to the 1965 election controversy in the West. The aftermath of those doctored figures[for increase revenue allocation and other benefits of population (number)] led to 1966 coup by Nzeogwu and all the military prophets that followed and their revenue distribution – “distortion” – formulas. Agreement (an instance is the Aburi agreement) were made to be honoured when breached. This remains the rule of the game.The principles of horizontal allocation of resources from oil between states and local governments changed rapidly and continuously as shown in table 1. This led to conflict after conflict within the polity, some violent and some not. To make their resolutions known, the regions and/or ethnic grouping and regrouping of the minority and disadvantaged communities made declaration, after declaration that stresses upon the need to control their resources and be compensated for the injustices suffered in the years past. They declare their resolve to free themselves from environmental degradation due to oil exploration and seek equity and justice. Each declaration has resource control and distribution as key words. The first being the Biafra declaration of secession on May 30, 1967 by Ojukwu, this was to be followed by a declaration of secession of the west by Awolowo, as agreed. But Awolowo did not declare (again the rule of the game: agreement honoured when breached). Instead, he (Awolowo) took a dual position in Gowon’s administration as minister of finance and a civilian head of government. This led to a 30 months civil war to unite Nigeria which ended on January 14, 1970. Thus, Gowon became an acronym for unity “Go On With One Nigeria”. That was just the beginning of not more civil wars but violent ethnic conflict in struggle for resource control. The painful aspect of this unjust allocation of revenue to the centre was the waste and embezzlement of the revenue from oil in the 1970s. The funds were wasted in events like, FESTAC – First World black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. Nigeria joined the ‘Dutch diseased’ nations and since then has become terribly sick. Looters and public treasury rapist emerged sweeping Nigeria (badly) clean[27].Those left out were the minorities from whose land the looted resources were exploited. The oil companies continue to operate insensitively, often times leaving the people with completely devastated environment; polluted seas and farmlands, without pipe-borne water, no schools, no health facilities nor electricity. Since what determines control was number or money power, the minorities were and are completely locked out while the majority continues to prosper through formulated-systematic revenue distribution - distortion - and looting. The minorities were tagged troublemakers for questioning government and private sector (oil companies) injustices and demanding control over their resources. For instance, in 1970 a major oil spillage occurred in the village of Ibubu, in Ogoni land, as a clean-up measure for millions of gallons of crude covering several hectares of farmland, Shell B.P. decided to set fire to the crude. How just is this action to the environment? The fire that burned for weeks created craters of six (6) to ten (10) feet deep and a soil crust laden with tar of more than ten (10) feet deep. If plant can never grow even after 30 years, what happens to the ground water? What about fishing, the major occupation of the area? In Akwa Ibom State, Eket, several spillages have been occurring but the June 1995 was the in the state. The January 1998 (40,000 barrels) spillage was believed to be one of the worst in the world[16].After years of unanswered protest to Shell and the Nigerian government, the stage was set for various other declarations. The Ogoni declaration was made in bills in 1990. They declared as follows: under the umbrella of MOSSOP:“….over 30 years of oil mining, since 1958 has left the people with: (i)No representation ….in all institutions of the federal government. (ii)No pipe borne water (iii) No electricity (iv) No job opportunities (v) No social and economic project of Shell / government.….that the people wish to manage their alter…”In response, in October 19, 1992 Decree No. 23 1992 establishing the oil mineral producing area development commission (OMPADEC) was promulgated by the government. The primary aim of OMPADEC was the rehabilitation of the environment and people of the oil producing areas. Did OMPADEC actually exist? Not in reality but in physical sense, Yes. It was only a smoke screen tactics of deceiving the illiterates in the oil producing countries[27], but for how long? Violence was created by the government and Shell B.P. between Ogoni and Andoni, Ken Sarowiwa and eight others were slaughtered and the communities destroyed by army[28]. This was not without an accomplice from ogoni, a sellout[16].In Akwa Ibom the struggle for crumbs, for who gets what, in terms of the meager loyalty on land and the utter neglect continually generated communal clashes and violent conflict. In January 1993 the two communities in question came “face to face.” Okposo, the disputed location was set ablaze. Explosives were used to blow up homes. Where did they get them from? Fishing equipment and properties worth millions of Naira were destroyed and lives were lost.Before the committee to settle the January conflict resumed, the worst happened in June 28 1993. Ibeno was attacked by Eket and Esit Urua kindred. As the fighting persisted evidence of strong military backing was uncovered. Production of oil was halted. That prompted the government to send the Nigerian Army to quell the crises. Millions of naira worth of properties and scores of lives were wasted again.

|

3. The Theories and the Road Not Tried

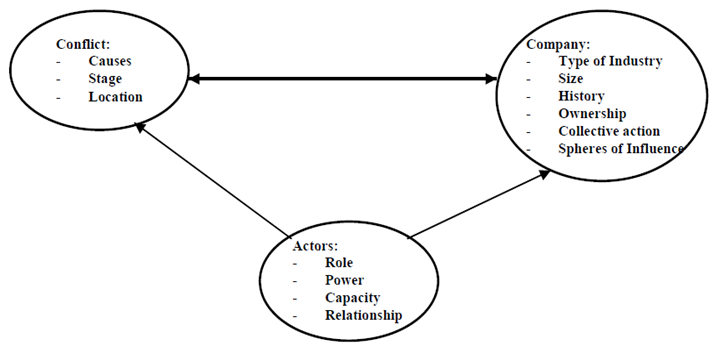

- Most of the existing literature on conflict and political economy of resource dependent states conclude or sometimes assume that the economic and political forces generated by inverse flow in export volume and revenue in natural resource-dependent states are so powerful that they distort any type of political structure. The relentlessness of these structural pull generated by oil exports persistently distort the best intention (if any) to sow the oil revenue, but instead results in economic deterioration, conflict and political decay. Some assign importance to state design while others argue that the decay is due to poorly organized economic sector[7,12,19].Most of the recommendation centers on changing resource and sectoral dynamics of these states. Collier[6] argues that economic diversification and poverty reduction are important in conflict prevention and recommends deregulation, improved transportation and reduction of barriers to information flow. However, suggestions are not made on reforms in government institutions that might reduce conflict. Also Herbst[10] notes that for countries at risk of conflict, the question of proper institutional design is exceptionally important. This holds true if changes in political dynamics surrounding government revenue are more tractable than changing the basic structures of the economy, at least through the medium term. Diversification of developing countries portfolio is exceptionally difficult and may be dependent on a host of issues outside the control of any government. In Nigeria, as observed by Ibeanu[30], the rules of the game are critical to the outcome of political conflict.Even in the unlikely event that resource dependence has dominated most institutional arrangement to date, there is still the possibility that countries could develop new institutional arrangement that would ameliorate or eliminate the correlation between resources and conflict. These inform the road not tried; partnership between government and the private sector through corporate social responsibility programme. Conflict resolution or management is not for the government alone. It requires the involvement of State and local entrepreneurs in the exploitation of the resources and sourcing for equipment and technology locally[31]. The private sector can be a force for conflict (www.globalissue) and for peace. Thus successful peace building process requires the support and involvement of the private sector and other stake holders. It requires the multi stakeholders approach.Nelson[17] outlines five (5) principles● Strategic commitment ● Analysis● Dialogue and consultations● Partnership and collective action● Evaluation and accountability (including sustainability)These principles suggest a generic framework for guiding the process of multi-stakeholder initiatives. The process is not rigidly chronological or independent stages in a process, but more akin to a jigsaw puzzle. It was first proposed by Global Compact and has been used in many countries successfully[5,9].Strategic commitment is a willingness to engage in the debate and basic recognition of partnership. It requires those who embrace the concept to develop attitude that influences others; persuading the skeptics. The analysis is illustrated in Figure 1. The figure shows that conflict does not exist without a company and the actors that represent the society or environment which the business operates. Therefore, conflict cannot be resolved without recognizing the business-conflict partnership and dealing with the conflict (causes, location, stage) in relation to the specified company variable (type of industry, size, history, ownership, collective action and sphere of influence) affected and the relevant actors (role, power, capacity and relationship).

| Figure 1. Analysis of Business and Conflict Partnership |

4. Summary and Conclusions

- The conflict situation in the Niger Delta of Nigeria manifest in diverse forms but can be traced to the advent of oil and lack of a fair institutional framework of revenue distribution. Where some exist, was created to be breached and bedeviled with unscrupulous legislatures that circumvent the true state of the “Cake Sharing” formula. The residents of this resource area suffer the exploitation effects without adequate indemnity[32]. Pollution, loss of property and lives to violent clashes, loss of soil fertility and negative effects on health are their reward. To them oil have actually become a curse.The theories suggest various measures, some feasible and others not. But given the pros and cons of existing literature, a new approach – the untried road – has been suggested. The drive for peace must go beyond government and the private sector, to other stakeholders. It requires themulti-stakeholders approach. This approach involves five (5) principles; strategic commitment, analysis, dialogue and consultation, partnership and collective action and evaluation, accountability and sustainability. This process guarantees peace and prevents conflict, and promotes political stability and the evolution of true federalism.

APPENDIX

- A CATALOGUE OF ESCALATING VIOLENCE IN THE NIGER DELTA 2003 – 20061. 2003 at Irri Isoko south local council, a traditional ruler was alleged to have sold the rights of the community to Agip Oil. This sparked off violence. And the end of the imbroglio, no fewer than ten persons died and properties worth millions of naira was vandalized, including the palace of the traditional ruler who took to his heels in the heat of the crises.2. 15th January 2003: Indigenes of Ohoror Uwheru community in Ugbelli North local council were attacked by a detachment soldiers from the joint security task force “Operation Restore Hope” 3. 23rd March 2003: while the security task force was on patrol off Escravos River, youth attack the team with 17 speedboats at Oporosa on the Escravos Creek killing three soldiers and one Naval Rating.4. 22nd March 2003: Youth struck at the TotalFinaElf tank farm in Oponani village and killed five soldiers and destroyed property worth billions of naira.5. 2nd May 2003: Barely 24 hours after the state house of assembly election, youth brandishing AK47 pump Rifles and other light weapons attacked the Naval base, leaving two Naval Ratings severely injured.6. 7th November 2003: 8 Mobile police men were reportedly killed by youths between Otuan and Oporoma in southern Ijaw local government area of Bayelsa state.7. April 2004: 5 persons including 2 Americans were killed by Militant youths. They were among the 9 people traveling in a boat along Benin River, west of Warri. When they came under what was described as “Unprovoked Attack”. The 2 American Expatriates were on the staff list of CheveronTexaco.8. January 2004: Suspected Itsekri Militants invaded some communities in Okpe Kingdom, killing 17 people and injuring 3 others.9. 14th April 2004: Ijaw youths attacked and killed 4 children and a 90 year old community leader, Madam Mejebi Eworuwo, in koko, head quarters of Warri North local council, Delta State.10. 23rd April 2004: About 9 members of the joint security task force “Operation Restore Hope”, in charge of security in Warri were killed by militant Ijaw youths.11. 2nd November 2004: for several hours, youths of Igbudu and soldiers of the joint task force clashed in igbudu area of Warri, Delta state.12. 18th November 2004: Ijaw youths from Odioma community in Brass council in Bayelsa State, protesting an alleged violation of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) by Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC), shut down and occupied its 8,000 Barrel per day flow station.13. 22nd November 2004: at least 17 youths of Ijaw extraction were confirmed dead as soldiers deployed to guard a flow station belonging to an oil servicing firm shot sporadically into a crowd.14. 28 November 2004: Ijaw youth clashed with soldiers at Beneseide flow station near Ojobo in Bayelsa state over breach of MOU.15. 23rd December 2004: the youths in Ogbe-Osewa and Ogbe Ilo quarters in Asaba clashed over a land dispute. Over 100 houses were ransacked, with property running into millions of Naira destroyed.16. 23rd December 2004: at Ekpan, Uvwie local council of Delta state youths clashed over the appointment of Unuevworo (Traditional head) of the community.17. 24th December 2004: Militant youths kidnapped 16 Oil workers, including a Yugoslav at Amatu community in Ekeremoh local council of Bayelsa state. They were kidnapped from a vessel identified as Seabulk, owned by an oil servicing firm, working with SPDC.18. 26th December 2004: Alleged similar breach of MOU by SPDC lead to the abduction of a Croatian worker, Mr. Ivan Roso, at the company’s sea eagle floating crude oil production facility.19. 21st December 2005: Explosion rocked Shell Pipeline in Niger Delta.20. 22nd December 2005: Fire raged in Shell installations causing 13 deaths.21. 12th January 2006: Pirates took four expatriates hostage.22. 16th January 2006: Militants Attacked another Shell platform and touched houseboats.23. 16th January 2006: 14 soldiers killed in Niger Delta shoot out.24. 18th January 2006: Soldier and Bayelsa Militants engage in gun duel.25. 18th January 2006: Shell cut output by 115 Barrels per day.26. 19th January 2006: Federal Government Open talks with militant27. 29th January 2006: Oil workers threaten to pull out of Niger Delta 28. 15th August 2006: Obasanjo order for security service to use “force for force” against Niger Delta Militants.29. 7th October 2006: Militant captured a barge of diesel fuel and kidnaps 25 shell workers.30. 3rd October 2006: 18 militants stormed Eket in Akwa Ibom state, and kidnapped 7 expatriate workers at an Exxon-mobile facility.31. 5th October 2006: Army of security forces allegedly razed the Ijaw village of Elem-Tombia in Rivers State.32. 11th December 2006: More than 500 young people representing about 500 communities and the 40 or so Ijaw clans, met in the town of Kiaiama to enforce the kiaiama declaration.33. 30th December 2006: Troops open fire on a 1000 strong protest march in Bayelsa Capital killing at least 3 people and wounding dozens, more that 20 people were reported killed in subsequent confrontation. A week after the first killing, estimate of the number killed by troops ranged between 26 and 240, and more that 90 houses were burned down.Source: The Guardian 13th February 2005 p. 26, various issues from December 2005 to January 2006 and other issues of The Punch and ThisDay, Gbomo, 2008 and Awuse, 2008

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML