Takashi Tsubakita1, Kazuyo Shimazaki2

1Department of Communication, Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Aichi, 470-0193, Japan

2Department of Nursing, College of Life and Health Sciences, Chubu University, Aichi, 487-8501, Japan

Correspondence to: Takashi Tsubakita, Department of Communication, Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Aichi, 470-0193, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The six dimensional factor structure of the Educational Need Assessment Tool for Nursing Faculty (FENAT) was examined through descriptive statistics and subsequent confirmatory factor analysis by using data collected from nursing teachers in nursing schools (not in universities) in Japan (N = 335 from 59 nursing schools; 322 women and 13 men; 77 were in their 30s, 167 in their 40s, 91 were over 50; 171 had less than 10 years’ teaching experience, 164 had more than 10 years’ experience). The participants were sampled as: (i) a single group and (ii) two independent groups divided by teaching experience. The results generally supported the de facto model but 10 out of 30 items showed the ceiling effect. Multi-sample analysis showed that all factor means of the FENAT in the group with over 10 years of teaching experience were lower than those of the group with less than 10 years of teaching experience. With some modification, this scale can be used for assessing the educational needs of nursing school teachers. However, it was suggested that further comparisons between these results and the results of analyses that use data from nursing faculties of nursing colleges/universities should be made before modifying the items in the FENAT.

Keywords:

Educational Needs, Nursing School Teachers, Teaching Experience, Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Cite this paper: Takashi Tsubakita, Kazuyo Shimazaki, Factorial Validity of the Educational Needs Assessment Tool for Nursing Faculty in Japanese Nursing School Teachers, Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 115-123. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20130304.01.

1. Introduction

An “educational need” in a teacher is defined as the discrepancy between an ideal state and an actual state as a professional teacher[1]. Having an educational need in one’s teaching means that one needs to be further educated in order to fill the gap in knowledge. Therefore, the more educational needs one has, the lower one’s state as a teacher is perceived. However, if a teacher has fewer educational needs, then it implies that he/she appreciates his/her qualifications as a teacher. It is widely accepted that improving the qualification of nursing teachers directly influences the quality of nursing education, and in the long run, clinical nursing activities[2]. This means that enhancing the qualifications and quality of nursing teachers or faculties is a pressing issue.In Japan, there are two types of institutions for nursing education: nursing colleges and nursing schools. Teachers in the latter should have at least 5 years of clinical experience and finished about a year of the nursing teacher training course laid down by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare[3].However, it is reported that 15% of nursing teachers in nursing schools do not meet the requirements specified by the Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry[7]. This could be due to chronic understaffing problems in nursing schools because of the high burnout and turnover rates in nursing teachers[4, 5]. In order to secure adequate teachers, local governments have provided various courses for nursing teachers, but the methods, attainment targets, and evaluations have not been standardized[6]. Concerned about these problems, the Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry has established a committee termed the “New Style of Nursing Teachers”[6]. In 2010, the Ministry developed the Guideline for Training Courses for Nursing Teachers and Guideline for Training Courses for the Head of the Instruction Department to be used by providers of training courses in local governments.Teachers who have finished the training course are considered to be full-fledged educators. After the training course, it is their own responsibility to cultivate their abilities as teachers. Each school is given full responsibility over the continuing education of nursing teachers after the training course. Only 8.3% of nursing schools evaluate teachers’ educational achievements, abilities, and research publications whereas more than 80% of nursing colleges and junior colleges evaluate them. Thus, most teachers in nursing schools have fewer opportunities to be evaluated according to their activities[7]. Indeed, nursing schools generally do not place faculty development as a top priority[8].Studies on the self-evaluation of educational activities in nursing teachers or faculties have revealed that teachers in nursing schools tend to evaluate their educational activities and abilities lower than those of faculties in nursing colleges[8]. Thus, it is important not to combine data obtained from samples from nursing colleges and nursing schools when we analyze educational needs in nursing teachers and faculties.The “Educational Needs Assessment Tool for Nursing Faculty” (FENAT) was developed by Yamashita et al. to assess educational needs in nursing teachers[2]. Since its development, this scale has been widely used in studies on Japanese nursing education[e.g., 8, 9]. Although Yamashita et al. conducted factor analysis with varimax rotation on the scale, the correlations between each factor are nevertheless hypothesized. Cronbach’s alpha was .95 in their study, which sampled 546 participants.To our knowledge, studies on the FENAT thus far have used exploratory factor analysis and multiple regression models[8, 9, 12]. Therefore, we decided to examine the robustness of the hypothesized six-factor structure by conducting confirmatory factor analysis. We examined the fitness of the hypothesized model on a representative sample of Japanese nursing school teachers (not from university nursing faculties). We decided to focus on teachers in nursing schools because the work environments of nursing faculties in universities are different from those in nursing schools, which could lead to different self-perceptions of educational needs, as mentioned previously. We decided to use covariance structure analysis to test the robustness of the model[10, 14]A study by Funashima et al. found a negative correlation between the amount of teaching experience and FENAT score (r = -.396, N = 546, p < .01)[11]. Therefore, based on this finding, we proposed the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 1: The six-factor model is the most fitted to the composite validation sample.Hypothesis 2: Years of teaching experience would affect the factor means.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

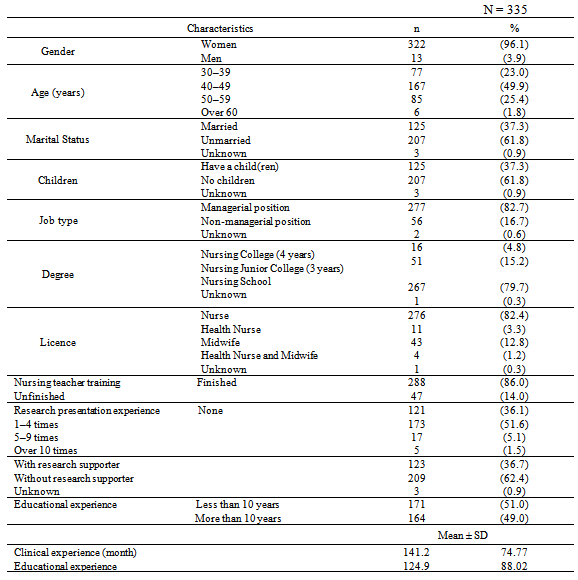

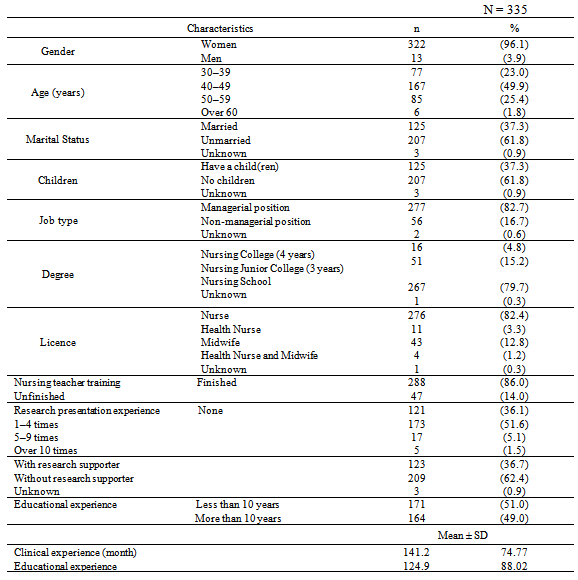

We selected 91 (all) nursing schools in the Tokai region in Japan and invited the administrators of these schools to participate in the study. We received positive responses from 59 schools. To increase the response rate of the surveys, we mailed the survey forms to the participating schools and requested the managerial staff to distribute, collect, and return the questionnaires together. The participants were informed of the purpose of the survey and asked to answer questions about educational needs and other related questions. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to any data collection.We asked respondents to specify their age only within a range and did not ask for any other identifying information. Each questionnaire was covered by a blank sheet of paper to protect the privacy of the respondent.Of the 613 questionnaires distributed, 396 were returned (response rate: 64.6%), of which 335 were included for statistical analysis. The sample consisted of 322 women and 13 men. Seventy-seven were in their 30s, 167 in their 40s, and 91 were over 50. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the participants.

2.2. Educational Need Assessment Tool for Nursing Faculty (FENAT)

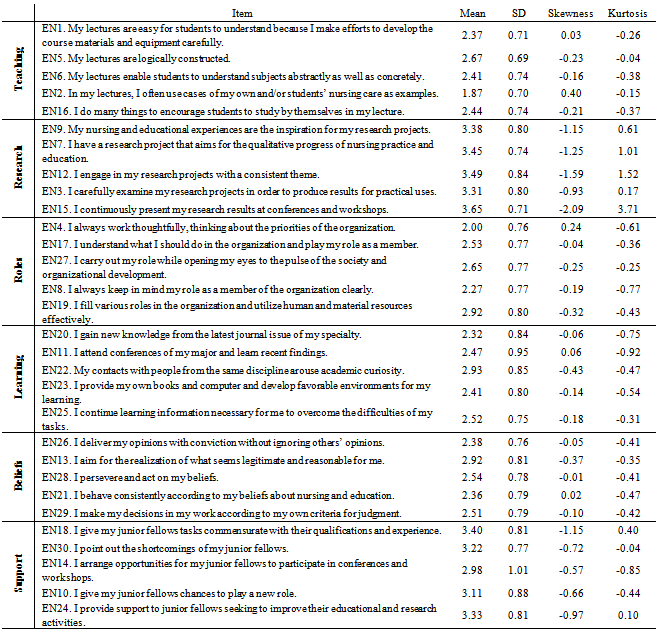

This scale includes the following six latent variables as factors: (i) providing high quality lectures (Teaching; e.g., “My lectures are easy for students to understand because I make efforts to develop the course materials and equipment carefully”), (ii) conducting research and giving the fruits of research back to communities (Research; “My nursing and educational experiences are the inspiration for my research project”), (iii) fulfilling multiple roles in the organization for the development of the organization (Roles; “I always work thoughtfully, thinking about the priorities of the organization”), (iv) continued learning for moreprofessional development (Learning; “I gain new knowledge from the latest journal issue of my specialty”), (v) autonomous teaching activities based on one’s own beliefs and values (Beliefs; “I deliver my opinions with conviction without ignoring others’ opinions”), and (vi) supporting the growth of junior fellows as professionals (Support; “I give my junior fellows tasks commensurate with their qualifications and experience”). Each latent variable is measured by five observed variables and rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 = to a very great degree, 4 = to a very little degree). There were no reverse-scored items. Higher scores indicate that one perceives more educational needs. Along with the FENAT, we asked for participants’ amount of experience in raising children, clinical experience, and teaching experience.

2.3. Analysis

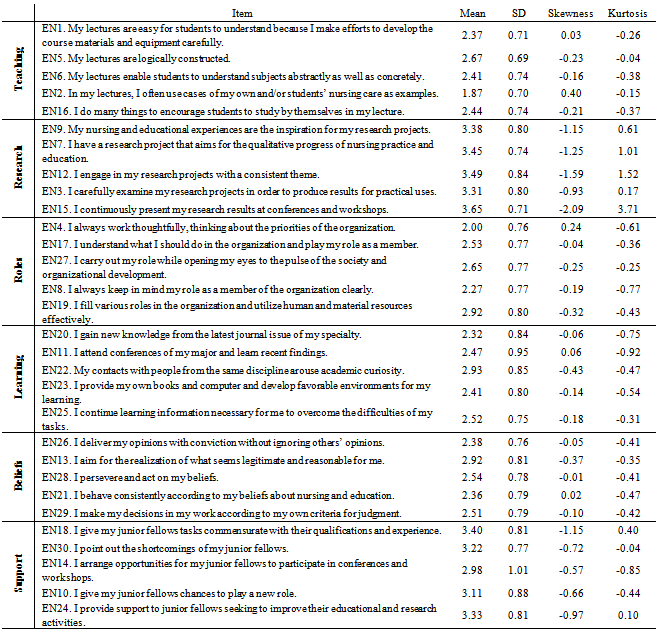

A previous study by Kameoka (2006) showed the floor effect in Items EN2 and EN4 and the ceiling effect in items EN3, EN12, and EN15[8]. If the same effects are observed in the same items in our sample, then the item(s) is considered to lead to a biased estimate. We therefore examined each item individually to determine whether the effects were observed. Table 1. Demographic information

|

| |

|

The validity of the six-factor structure was evaluated by a composite validation sample (N = 335 as a single sample). We examined whether the de facto six-factor model is the best fitted to the sample compared to (i) the null model in which no single latent factor was supposed and (ii) a factor model in which all items were influenced by only one latent factor. If the fitness indices of the six-factor model were better than those of these two models, then the hypothesized factor structure is said to be appropriate and will be evaluated for the robustness of the structure through cross validation samples. If the six-factor model is not better than (i) or (ii), then we will conduct exploratory factor analysis or revise the six-factor model.Next, we divided the sample into two groups (A: less than 10 years of teaching experience and B: more than 10 years of teaching experience) as the cross validation samples to evaluate the fitness of the six-factor model. If the model fits the two different groups well, then we can confirm that the model is robust.Finally, we examined the invariance of the measurement in order to calculate and compare the factor means across the two groups.In this study, all models were analyzed with the maximum likelihood estimation through AMOS 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

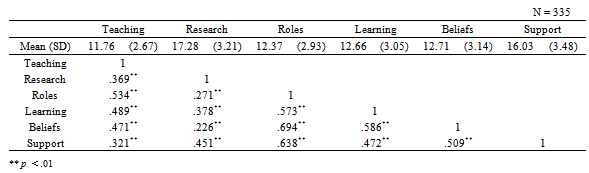

Table 2. Correlations among factors

|

| |

|

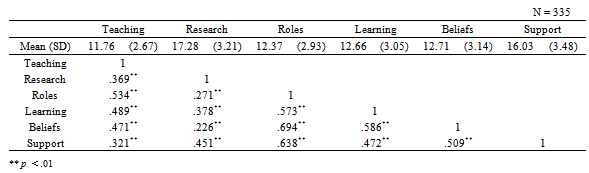

The descriptive data of each item are shown in the Appendix and in Table 2. The ceiling effect was observed in Items EN3, EN7, EN9, EN10, EN12, EN15, EN18, and EN24, and in the sums of the items in the factors Research and Support. Items EN14 and EN30 showed a slight tendency toward the ceiling effect. There were strong correlations between the factors, especially between the factors Beliefs and Roles. Results of an independent-samples (less than 10 years’ experience and more than 10 years’ experience) t-test revealed significant differences in the means of Roles (t (333) = -4.51, p < .00), Beliefs (t (333) = -2.99, p < .01), and Support (t (333) = -6.82, p < .00).

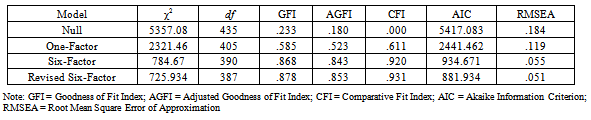

3.2. CFA (1): Composite Validation Sample

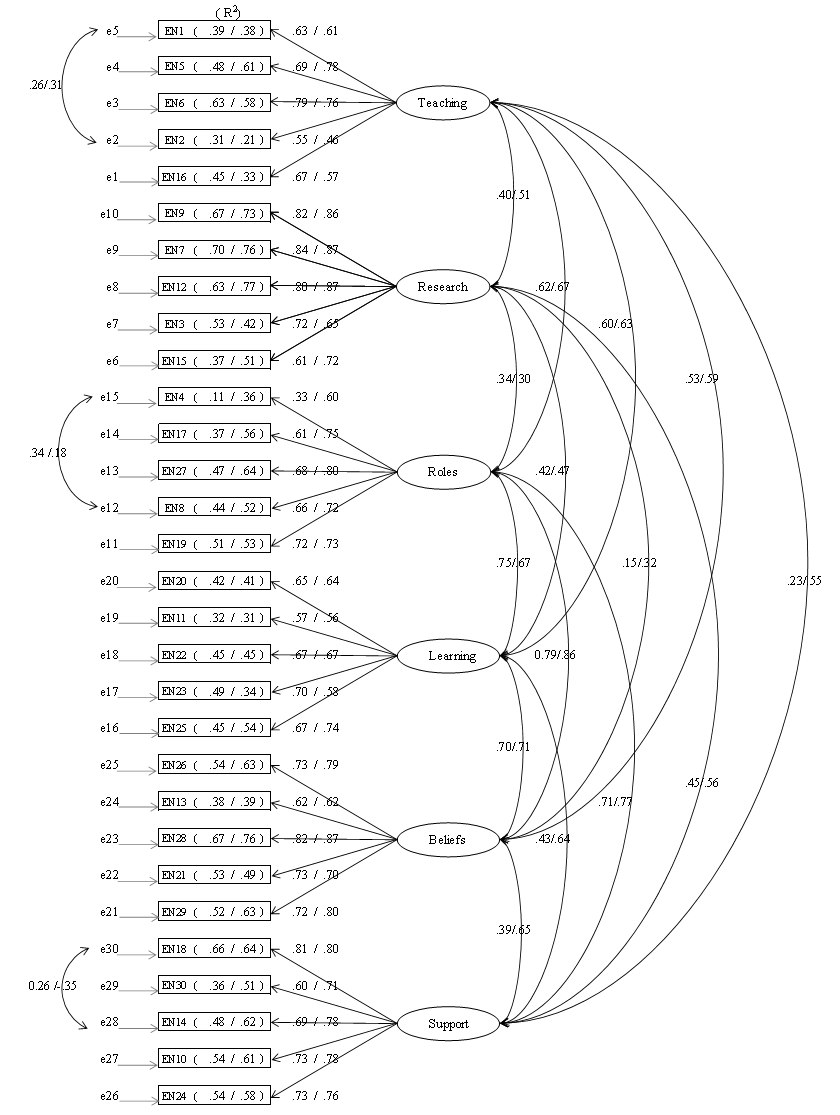

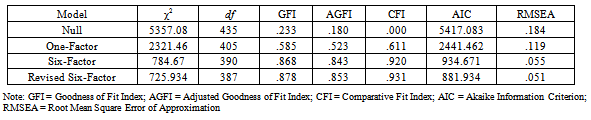

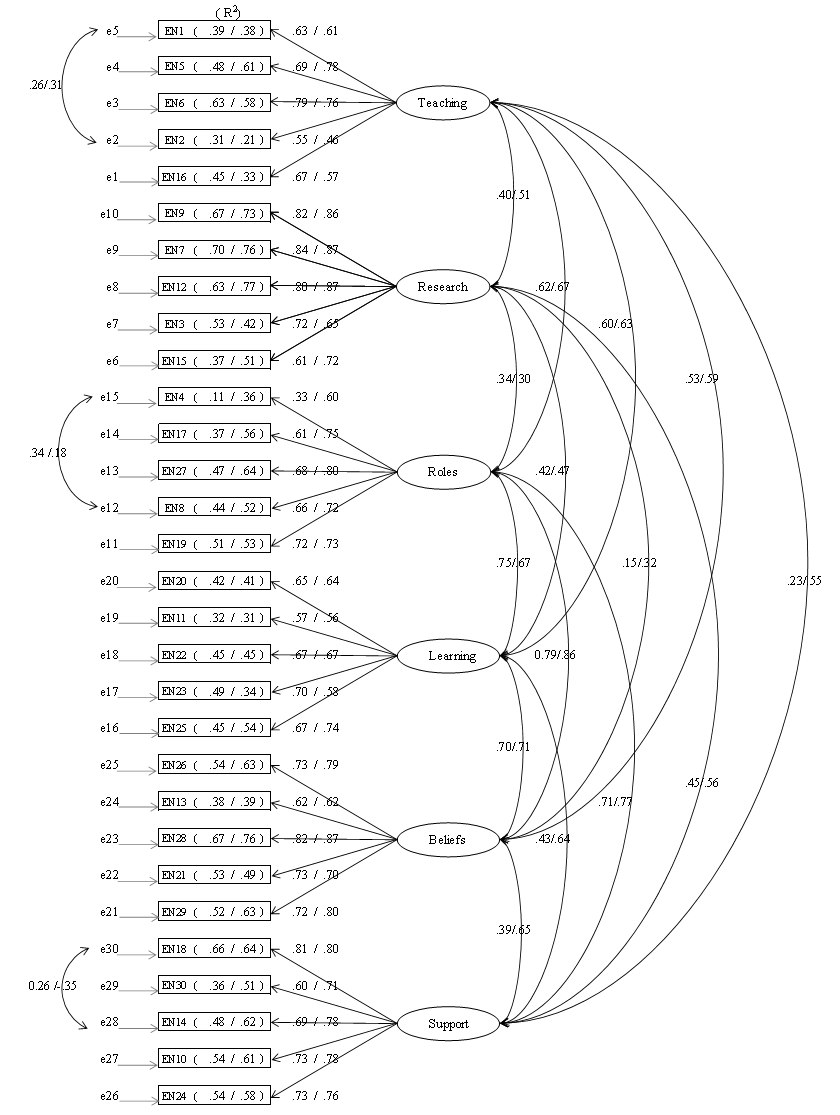

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on a composite sample (N = 335). The model-fit statistics for three substantive models are shown in Table 3. The fit of the hypothesized six-factor model to the data was better than that of the null model and the one-factor model, suggesting that the factor structure of the FENAT can be considered to contain the hypothesized six factors developed by Yamashita et al. (2004).However, the CFI (Comparative Fit Index) of the six-factor model was slightly below the Hu and Bentler criterion[14, 15] of .95, suggesting that some modification of the six-factor model is needed. Therefore, we attempted to modify the model by referring to the modification indices provided by AMOS.We constructed three new paths between error variables, as shown in Figure 1. This modification slightly improved the fitness of the model to the data. Therefore, we retained this revised six-factor model as a baseline model for this study. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

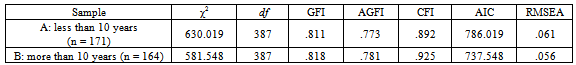

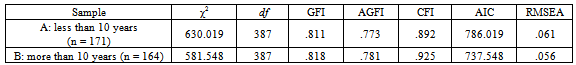

3.3. CFA (2): Cross Validation Samples

Next, the revised six-factor model was tested according to the amount of teaching experience (less than 10 years (A) or more than 10 years (B)). Fit statistics are shown in Table 4. The CFI of Group A was slightly under .90 and the AIC of Group A was larger than that of Group B, suggesting that there is some kind of model variance between the two groups. The RMSEAs of each group were under .10, which meets their respective criteria. To examine the existence of variance across the groups, we conducted multi-group analysis for groups A and B.

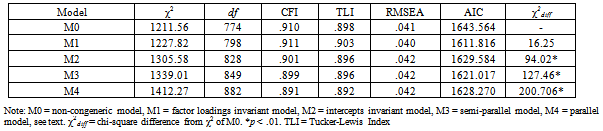

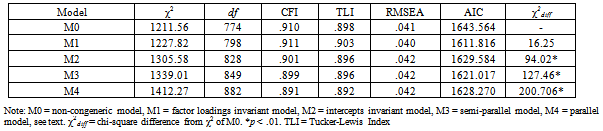

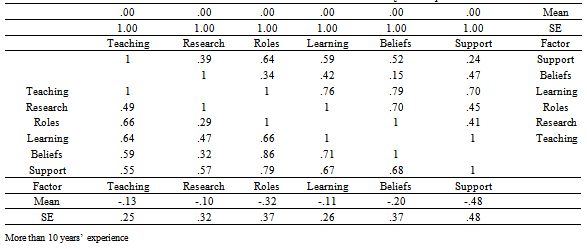

3.4. Multiple Sample Analysis

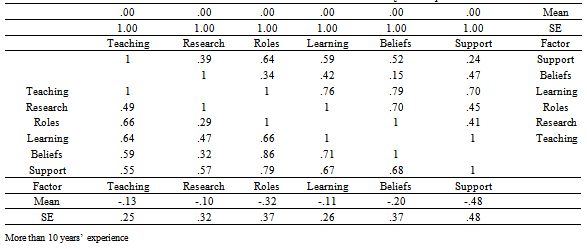

1) Analysis of Factor Loadings Invariance and Factor Variance-Covariance InvarianceBefore examining factor means across groups, we should examine the factorial invariance model and measurement invariance model to determine whether both models are confirmed by the data.As shown in Table 5, the non-congeneric model (M0) did not contain any equality constraint. The analysis of the factor loading invariance model (M1) is to examine whether each six-factor pattern in the baseline model is invariant across groups A and B by ensuring that every factor loading from the latent variables to relevant items has the same value across the groups. For example, the value of the factor loading from Teaching to Item 1 (EN1) in Group A is constrained to be equal to the value in Group B. The factorial invariance and measurement invariance models were both approved through this analysis. We then examined additional models as follows.We constructed models in order to examine the invariance of intercepts (M2), factor variances and covariances between factors (M3), and error variable variances and three covariances (M4). In M2, the invariance of each intercept was constrained to be equal. In M3, each factor loading, factor variance, covariance between factors, and intercept was constrained to be equal across the groups. In M4, the variances of each unique variable and covariances between unique variables (i.e., e2–e5, e12–e15, and e28–e30) are constrained to be equal across the groups in addition to the constraints in M4.Therefore, M2 contains the constraints of M1, M3 the constraints of M2, and M4 the constraints of M3. The results of a χ2 test suggest that the increase of the χ2 value from M0 to M2, M3, and M4 were significantly larger than the increase in the degree of freedom, meaning that there are non-invariance anywhere across the groups. We then tested the fitness of models in which every corresponding factor loading and correlation between factors were constrained to be equal across the groups, except any one of the parameters. In other words, only one pair of parameter was not constrained to be equal. We found that factor loadings to Items EN4 and EN23 were not invariant at p < .10 and p < .05, respectively, and the correlations between Research and Beliefs and between Research and Roles were not invariant at the p < .10 level. The model fit improved significantly than M4 at the p < .05 level after we excluded these four constraints.2) Factor MeanWe constrained each corresponding intercept of the observed variables to be equal (e.g., intercept of Item 1 in the under-10-year group = intercept of Item EN1 in the over-10-year group, and so on), and constrained each mean and variance in the under-10-year group to be 0.00 and 1.00, respectively. In this analysis, the less than 10 years’ group functioned as the reference group. In other words, the factor means in the more than 10 years’ group represent the relative deviation from those of the reference group. This analysis allows us to compare the factor mean in each factor across the two groups. Table 6 shows the results of this analysis.Generally, all factor means in the more than 10 years’ group were smaller than those of the less than 10 years’ group. Specifically, the effect sizes (standardized mean differences) of Roles and Support between the two groups were .39 and .56, respectively (Table 6, see[13] for the calculation of factor means). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.Table 3. Fit statistics of the composite validation samples

|

| |

|

Table 4. Fit statistics of the cross validation samples

|

| |

|

Table 5. Multi-sample analysis of the cross validation samples

|

| |

|

Table 6. Correlations between factors and factor means of each age group

|

| |

|

| Figure 1. Standardized estimates in groups A (less than 10 years’ teaching experience) and B (more than 10 years’ teaching experience), respectively. Note: All parameter estimates in this model are significant at the p < .01. “e”: error variables that influenced each item. The one-way arrows from the five factors to each item represent factor loadings. The two-way arrows between factors represent correlations |

4. Discussion

4.1. Ceiling Effect of the FENAT

As noted in 3.1, ceiling effects were observed in items EN3, EN7, EN9, EN12, EN15 (in Research), EN10, EN14, EN18, EN24, and EN30 (in Support), meaning that the participants generally felt educational needs in the domains of research and support. Although we did not observe the floor effect in items EN2 (“In my lectures, I often use cases of my own and/or students’ nursing care as examples”) or EN4 (“I always work thoughtfully, thinking about the priorities of the organization”), the means of these items were the lowest. The descriptive statistics of our study showed generally the same result as that in Kameoka (2006). As to the domains of Research, the results seemed to reflect the fact that most nursing schools do not provide enough opportunity and financial support for teachers. For those teachers who are engaged in research, items in the factor Research set an anticipation of a high standard of research; even if participants advance their own research, they would underestimate their results and express it modestly because their research environments are usually poorly funded and most nursing school teachers do not participate in any academic meetings in which members should have at least a bachelor or master degree. Indeed, in our sample, about 80% of participants do not have a bachelor degree (see Table 1). Most items generally contain two or three aspects of each relevant factor, which could lead to ambiguity and thus make it difficult for participants to respond. We therefore suggest that these items be divided into two or three sub-items. For example, Item EN7 “I have a research project that aims for the qualitative progress of nursing practice and education” could be re-written as (1) “My research project is aimed for the qualitative progress of the nursing practice” and (2) “My research project is aimed at the qualitative progress of nursing education.” This would enable a more accurate measurement of the factor.The items in the factor Support were designed for teachers who have junior coworkers. For example, Item EN10 (“I give my junior fellows chances to play a new role”) would naturally elicit more positive responses (lower scores) from participants with more experience because only those with enough teaching experience could guide junior fellows. This would result in Group A scoring higher on this factor than Group B, which is indeed shown by the results of the t-test. In addition, these items should be rewritten in accordance with the Japanese cultural context, where euphemistic expressions are used to avoid conflicts with others. For example, Item EN30, “I point out the shortcomings of my junior fellows” can be rewritten as “I encourage my junior fellows to advance their growth as teachers” because the phrase “I point out shortcomings” can be interpreted as denying junior fellows’ qualifications as teachers.

4.2. Validity of the Six-Factor Model in the FENAT

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis with our full sample as the composite validation sample indicated that the hypothesized six-factor model is adequate although three correlative paths were constructed in several error variables. The CFIs of the baseline model in the confirmatory factor analysis were slightly under the .95 criterion of Hu and Bentler although the values satisfied the .90 benchmark criterion. In this regard, we can conclude that the FENAT contains the hypothesized six factors. Analysis of this baseline model with the cross validation samples confirmed the robustness of the hypothesized six-factor model. Although the CFI of the model for Group A did not fit very well to the data, this result is considered to reflect the inadequacy of our hypothesis, not the model per se. Indeed, we could have divided the sample by, for example, seven or twelve years of experience instead of ten years.

4.3. Multi-group Analysis

The test of the factor structure invariance (M0) and measurement invariance (M1) models was conducted for groups A and B and revealed that both models were fitted to the given data. We can thus assume that each of the six factors influenced the observed variables in the same way across the groups.Subsequent analysis of factor means indicated that the means of Support and Roles differed between groups. These discrepancies are probably due to extra factors such as position or amount of educational experience, as discussed in section 4.1. Therefore, these items in Support and Roles have much room for improvement.However, we were unable to confirm the models that contained strong equivalent constraints (M2–M4). Therefore, we can assume that there are non-invariances in the covariances between Research and Beliefs (.15 in the less than 10 years’ group vs. .32 in the more than 10 years’ group), and between Research and Roles (.34 vs. .29), at the p < .10 level. These invariances seemed to reflect differences in how both groups evaluated their research activities. Apart from the ceiling effects, the most prominent item to be addressed is Item EN23 (“I provide my own books and computer and develop environments that are favorable for my learning”). This item was problematic because it contains the words “books” and “computer,” which may not necessarily be related to the development of a favorable environment for learning. In addition, this item is ambiguous because it does not specify whether it is referring to an environment for learning in one’s workplace or in some other place. This is considered to account for the negative response to this question.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the factor structure of the FENAT on a sample of nursing school teachers in Japan. The hypothesized six-factor model, factor structure invariance model, and measurement invariance model were generally confirmed. It was indicated that there were mean differences in the factors Roles and Support between the two groups of participants divided according to the amount of teaching experience. We suggested that several items be re-written to reduce the ceiling effects due to factors other than the six hypothesized factors, such as modesty, status, or age. However, this suggestion for the modification of items does not necessarily mean that the items can be rewritten adequately to be administered to both nursing school teachers and nursing faculties in colleges/universities. In other words, before revising the FENAT, we should conduct the same analysis on a sample of nursing faculties in nursing colleges.

Appendix

Items and factors of the Educational Need Assessment Tool for Nursing Faculty

References

| [1] | Funashima, N., Murakami, M., and Kameoka, T. 2006 Development of Educational Needs Assessment Tool for Nursing Faculty: FENAT. Nursing Education, 47(4), 350-355. |

| [2] | Tajima, K. 1989 Fundamentals and Practices of Evaluation in Nursing Education. Igaku-shoin, Tokyo. |

| [3] | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Guideline For Nursing Schools, final revision at Feb. 14, 2013; http://law.e-gov.go.jp/htmldata/S26/S26F03502001001.html |

| [4] | Miyaji, F., Nakazaki, K., Nogawa, T., Kouda, N., Watanabe, H., Ishida, Y., Yajima, C., Tsukakoshi, S., Hattori, M. 2003 Study on the Education Program for Nursing School Teachers. The Bulletin of Saitama Prefectural University, 5, 133-138. |

| [5] | Sakai, K. 2005 Developing a Scale for Evaluating Stressors on Teachers at Nursing Schools, Journal of Japan Society of Nursing Research, 28(5), 25-35. |

| [6] | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2010 Report on New Style of Nursing Teachers. [Online]http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2010/02/dl/s0217-7b.pdf |

| [7] | Japanese Nursing Association. 2000 Research of Nursing Education;http://www.nurse.or.jp/home/publication/seisaku/pdf/62.pdf |

| [8] | Kameoka, T., Funashima, N., Yamashita, N. 2006 Educational Needs of Nursing Faculty: Current Status and Related Factors. Journal of Japanese Society of Nursing Research, 29(5), 27-38. |

| [9] | Isshiki, H. 2007 Association between Sense of Coherence and Educational Needs in Nursing Teachers. Reports of Nursing Research. Nursing Teacher’s Course of Center for Professional Education, Kanagawa University of Human Services, 32, pp. 39-46. |

| [10] | Toyoda, H. 1998 Covariance Structure Analysis, An Introduction. Asakura-shoten, Tokyo. |

| [11] | Funashima, N. (ed.) 2006 Assessment Tools File for Nursing Practices and Education: Developing Process and Applications. Igaku-shoin, Tokyo. |

| [12] | Funashima, N., Murakami, M., Kameoka, T., Miura, H., Yamashita, N. 2006 Educational needs of nursing faculty: current status and related factors. Nursing Education, 47(4), 350-355. |

| [13] | Toyoda, H. 2007, Covariance Structure Analysis: For the Amos user. Tokyo-tosho, Tokyo. |

| [14] | MacCallum, R. C. & Austin, J. T. 2000 Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Psychological Research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 201-226. |

| [15] | Hu, L., Bentler, P.M. 1999 Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6(1), 1-55. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML