-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2012; 2(5): 74-82

doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20120205.02

The Effects of Task Interdependency on Cooperative and Competitive Group Processes: An Example of Scheduling Audit Engagements

ToddL. Sayre, Carol M.Graham

School of Management, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, 94117, USA

Correspondence to: Carol M.Graham, School of Management, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, 94117, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Our study investigates and tests the interaction of cooperative and competitive group processes and high and low task interdependencies on performance in scheduling staff auditors to audit areas. The task examined is the scheduling of staff auditors to audit areas. In one case, we assume managers schedule staff auditors to audit areas and in the other we assume staff auditors schedule themselves to audit areas. We measure performance as the total expected time of those scheduled to complete the audit areas, where less time translates to better performance. Task interdependency varies depending on who performs the task. When managers schedule audit areas, task interdependencies arise related to information and scarce human resources, neither of which exist when staff auditors schedule themselves. Accordingly, because of the difference in task interdependencies, cooperative and competitive group processes result in larger performance differences for managers scheduling staff auditors than for staff auditors scheduling themselves. The results of our laboratory experiment support this conclusion.

Keywords: Audit Scheduling, Task Interdependency, Group Processes

Cite this paper: ToddL. Sayre, Carol M.Graham, "The Effects of Task Interdependency on Cooperative and Competitive Group Processes: An Example of Scheduling Audit Engagements", Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 74-82. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20120205.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Group decision making plays a central role in public accounting firms. For example, auditors working together in conducting and interpreting fieldwork results in many forms of group decision making. On broader issues, such as in setting firm policy or in acquiring a new client, the decisions of one auditor indirectly affect the decisions of other auditors. Despite its importance, little research on judgment and decision-making considers the multi-person component of the auditing environment. Literature reviews of both[1] and[2] note the need for additional research in this area. More specifically,[1] encourage studies" ... on the interaction of type of group process and type of task: that is, one kind of group may do better at one task, another kind at another task" (p. 424). Such studies, they contend, do not exist in the accounting literature and therefore would add to our understanding of the way auditing and other accounting work is organized.Surprisingly,[1]’s call has gone virtually unanswered in the nearly 20 years since it was first made.One important aspect of group decision making is that cooperation does not always improve performance. For example,[3] contrary to their prediction report no performance difference between competitive and cooperative groups. One explanation involves what the psychology literature refers to as task interdependency. Tasks with low interdependency are solvable without the help of other individuals while tasks with high interdependency can be resolved through a mutual exchange of ideas and information[4]. If the task used in[3] had low interdependency and therefore could be accomplished without assistance, we would expect no difference in performance between competitive and cooperative incentive schemes. The effects of task interdependency on group decision making have direct implications for organizations. Those organizations that distinguish between tasks with high and low interdependency benefit because they can focus their efforts on the tasks that have the potential to yield performance improvements. For instance, organizations will not waste their time changing from competitive to cooperative incentives for tasks with low interdependency. Instead, they can focus their efforts on improving performance on the tasks with high interdependency. Clearly, an organization benefits when it distinguishes between tasks with low interdependency, where performance cannot be improved, and tasks with high interdependency, where performance improvements are possible. For the tasks with high task interdependency, the organization providing competitive incentives can improve performance in two ways. First, as previously discussed, it can change its incentives from competitive to cooperative. Second, it can reduce the interdependency involved with task. In the psychology literature, experimenters typically reduce interdependency by providing subjects with the necessary information to solve the task without assistance. Understanding that two options exist to improve performance potentially benefits the organization. For example, the organization that does not want to switch from competitive to cooperative incentives can still improve performance by reducing task interdependency. The organization that understands these options will benefit since it can choose between switching incentives or reducing interdependency based on its overall strategic goals. The role of task interdependency is especially important to accounting firms since many tasks involve group decision making. Some of these tasks that auditors perform under competitive incentives involve high interdependency, and are therefore prime candidates for improving performance. One such task is the scheduling of staff auditors. We argue that a firm can improve its scheduling efficiency, the total expected time to complete all audit areas, in two ways. First, by providing managers with cooperative rather than competitive incentives and second by allowing staff auditors to schedule themselves. Our study makes several contributions to the literature on multi-auditor decision making. First, it responds to[1] in that we investigate the interaction of two types of group processes (cooperative and competitive) and two types of tasks (high and low interdependency). Second, our findings imply that accounting firms can vary task interdependency by changing the individual assigned to the task. Therefore, if a firm determines whether its incentives elicit competitive or cooperative behavior, it may, through the individual it assigns to the task, vary task interdependency in its favor. For example, our study suggests that if accounting firms provide competitive incentives they may improve performance by allowing staff auditors to influence their schedules. Alternatively, if the firm wants managers to schedule staff auditors, they can still improve performance by implementing more cooperative incentives. The next section provides a review of the literature on task interdependency, scheduling and performance which is followed by the theory and hypothesis development section. The last two sections are the results and conclusion, respectively.

2. Literature Review

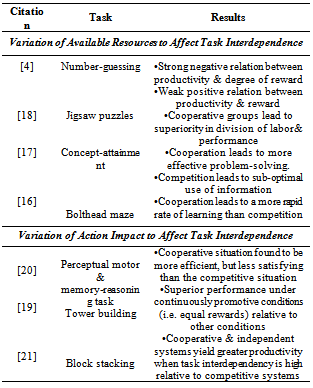

- The seminal study of[5] outlines a theory of cooperation and competition related to small group interaction. While previous studies (e.g.[6]) concentrate primarily on the individual motivations and goals intrinsic in cooperation and competition,[5] emphasizes the importance of interactions between individuals. Reference[5] argues that cooperation facilitates increased coordination of efforts, division of labor, and helpfulness toward each other. In contrast, competition for scarce resources pits group members against each other. Therefore,[5] argues, competitive groups lack coordination, role differentiation, and members of the group will obstruct the efforts of others. As a consequence of these effects on group processes,[5] hypothesizes thatcooperative groups, qualitatively and quantitatively, outperform competitive groups. This hypothesis engendered many studies examining the effects of competitive and cooperative reward structures on group productivity. These studies yielded some interesting, although many times conflicting, results. Many studies found that compared to competitive reward structures, cooperative reward structures increased group productivity. For example,[7] gave groups of 15 to 21 subjects the task of using a string to pull cones out of a glass bottle. The neck of the bottle required that only one cone was removed at a time. As predicted, serious "traffic jams" developed when subjects were paid by competitive as opposed to cooperative rewards. The results of the experiment support[5]'s prediction that cooperative groups produce more than competitive groups. Other studies found that cooperative reward structures decreased group productivity or had no effect compared to competitive reward structures (e.g.[8]). Reference[4] were the first to offer an explanation for these ambiguous results (also see[9]).Reference[4] distinguishes between tasks of high interdependency, which involve a mutual exchange of ideas and information for resolution, and tasks of low interdependency, which are solvable without the help of other individuals. Of 24 previous studies on cooperative and competitive reward structures and group productivity,[4] classified 6 that involved high task interdependencies and 18 that involved low task interdependencies. The results of all 6 of the high interdependency tasks indicate that competitive reward structures decrease group productivity. Fourteen of the 18 of the low interdependency tasks indicate that competitive reward structures increase group productivity while the remaining 4 studies indicate the inverse relationship. As[4] note, the 4 exceptions indicate either that, in the low interdependency situation, the positive relation between group productivity and competitive reward structures is weak or that there is another confounding variable. To address this issue,[4] analyzed the magnitude of the differences in nine earlier studies. Studies with low task interdependency by[8],[10],[11],[12],[13], and[14] were compared to studies with high task interdependency by[15],[7] and[5]. For low interdependency tasks, reward structure explained only .04 of the variance in productivity, while, for high interdependency tasks, .42 of the variance in productivity was explained by reward structure. In sum,[4] maintain that under conditions of high (low) task interdependency, the amount of group productivity varies inversely (positively) with the degree of differential rewarding for relative productivity. Furthermore, low interdependency tasks generally results in smaller productivity differences favoring competitive reward structures than those of high interdependency tasks favoring cooperative reward structures. Since[4], several experimental studies, employing a variety of tasks, have examined the interaction between reward structures and task interdependency. Typically, these studies operationalized task interdependency in one of two ways. Numerous studies varied the availability or supply of resources, making sharing advantageous (e.g.[16],[17],[4]). For example,[18] provided pairs of subjects seated near each other with the task of assembling identical jigsaw puzzles. They varied information sharing by varying one subject's visibility of the other subject's puzzle pieces. When view of the puzzle was impeded (low interdependency), pairs paid according to cooperative and competitive reward structures performed equally. In contrast, when the pairs of subjects could easily view each other's puzzles (high interdependency), they performed better under the cooperative reward structures than they did under the competitive reward structure. Other researchers operationalized task interdependency by varying the extent to which the action taken by group members in accomplishing a task affects the ability of other members to complete any part of the task (e.g.[19],[20]). For example, the task of[21] required subjects to build towers by stacking blocks on top of each other. The high interdependency task required that subjects, as a group, build a single tower, while in the low interdependency task, subjects built their own individual towers. Again, in the high interdependency task, subjects under the cooperative reward structure performed better than they did under the competitive reward structure and, in the low interdependency task, subjects performed equally. Table 1 summarizes these papers.

|

3. Theory

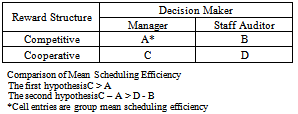

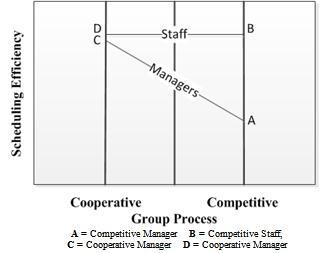

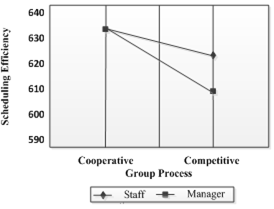

- In this section, we examine the effects of high and low task interdependency and competitive and cooperative incentives on scheduling audit areas. The dependent variable we use to measure performance under the 4 scenarios is the total time we would expect staff auditors, after they are scheduled, to spend completing all audit areas. We will refer to a set of schedules with a low total expected time as having high scheduling efficiency. We argue that a firm can affect scheduling efficiently by varying incentive scheme or task interdependency. Moreover, we show that a firm can affect task interdependency depending on whetherit has managers schedule staff auditors or staff auditors schedule themselves. The competitive incentives we use in our examination differ between managers and staff auditors. We assume that, holding all else constant, a manager whose audit requires less time relative to the audits of other managers receives higher pay. Alternatively, the performance of a staff auditor varies according to the time he is under or over the budget on his audit area compared to the time other staff auditors are under or over their budgets. The staff auditors receive higher (lower) pay for the time by which they are under (over) budget relative to other staff auditors increases. These competitive incentives for the manager and for the staff auditor are not inconsistent with the actual incentives provided by public accounting firms. For cooperative incentives, we assume that the pay of both managers and staff auditors increases with scheduling efficiency.Our first hypothesis concerns the effect of task interdependencies and cooperative and competitive incentives on managers scheduling staff auditors to audit areas. Suppose two managers A and B each need to schedule one staff auditor to their respective audit engagements. Manager A needs a staff auditor to audit cash and manager B needs a staff auditor to audit a pension. Two auditors, an experienced senior and an inexperienced assistant, are available. The senior audits pension areas much faster than the assistant auditor, but audits cash areas only slightly faster than the assistant auditor does. Therefore, these auditors would be efficiently scheduled only if the senior audits manager B's pension area and the assistant audits manager A's cash area. In this situation, two interdependencies exist, one related to information and the other to the scareresource of skill. Related to the information interdependency, managers know the area they need to audit and can estimate the skills of the auditors; however, they do not know the areas that other managers need to audit. Therefore, managers A and B are unable to consistently schedule staff efficiently (e.g. staff on cash and senior on pension) unless they share information on each other's needs. Related to skill as the scarce resource interdependency, a manager in scheduling a staff auditor simultaneously precludes other managers from scheduling the same auditor to their areas. Therefore, in our example, without manager A's help, manager B would be unable to consistently schedule staff auditors efficiently; for manager A, when he chose first, would schedule the senior to cash and manager B would be forced to schedule the assistant tothe pension area.Given these interdependencies, previous research suggests that if the managers cooperate, scheduling efficiency will be higher than if they compete. This is because if the managers cooperate, they will share information regarding their audit needs and manager A will schedule the assistant to audit cash and leave the senior for manager B's pension area. Accordingly, we state the first hypothesis in the alternative form. H1: Managers in cooperative groups schedule staff auditors more efficiently than do managers in competitive groups. Some firms may find it difficult to entice managers to cooperate. Therefore, our second hypothesis concerns the effects of task interdependencies and cooperative and competitive incentives on staff auditors scheduling themselves to audit areas. We assume that managers make their area budgets available to staff auditors prior to scheduling and that the budgeted hours for each audit area are based on an average expected hours of all auditors' to complete each area. Recall that when managers scheduled staff auditors, two interdependencies related to information and scare resource of skill arose. When staff auditors schedule themselves, two similar potential interdependencies arise, one related to information and the other related to the scarce resource of audit areas. Related to the information interdependency, staff auditors can estimate the hours it would take to complete each audit area on the budgets; however, they do not know the expected hours of other staff auditors for each audit area. Related to audit areas as scarce resource, a staff auditor in scheduling himself to an audit area simultaneously precludes other auditors from scheduling themselves to that area. We argue that these potential interdependencies, unlike when managers schedule auditors, have no effect on scheduling efficiency when staff auditors themselves. By having managers base their budgets on the average of the hours they expect each staff auditor would take to complete their areas, the interdependency related to information diminishes. This is because the difference between an auditor's expected hours for an audit area and the average expected hours for the area reveals the auditor's relative skill in that area. If an auditor's expected hours are lower than the average, he will expect to complete the area under budget, and the extent of the difference reveals by how much he can expect to be under budget. Related to the scarce resource of audit area, an auditor that schedules himself to where his relative skills are highest does not preclude other auditors from scheduling themselves to areas where their relative skills are highest. Accordingly, relative to when managers schedule staff auditors, when staff auditors schedule themselves, task interdependencies related to information and scare resources decrease. Related to information, whereas managers need to share information to schedule efficiently, the staff auditors can schedule themselves efficiently without sharing information. Related to scarce resources, a staff auditor who schedules himself to the audit area where his skills are relatively highest, will not affect the decisions of other auditors. As discussed in the literature review, as task interdependencies decrease, differences in scheduling efficiency between cooperative and competitive group processes decrease. Therefore, if all of the staff auditors schedule themselves to the areas where their relative skills are highest, they minimize the expected time spent for all audit areas (i.e. scheduling efficiency is maximized). Accordingly, we state the second hypothesis in the alternative form. H2: The difference between scheduling efficiency under competitive and cooperative reward structures is greater when managers, rather than staff auditors, schedule audit areas. Specifically, the scheduling efficiency of managers under cooperative incentives is the same as that of staff auditors and under competitive incentives is less than that of staff auditors. Figure 1 graphically illustrates our hypotheses. Moving from cooperative to competitive reward structures, we expect staff auditors to show no difference in scheduling efficiency and managers to decrease in scheduling efficiency. We also expect that staff auditors scheduling efficiency under both reward structures will be identical to managers scheduling efficiency under the cooperative reward structure.

| Figure 1. Expected Relationships |

4. Experiment

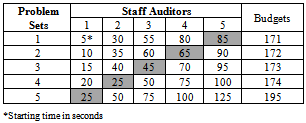

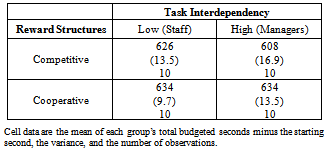

- The experimental design is a 2 x 2 factorial. The factors are the subject's reward structure (cooperative vs. competitive) and the subject's decision-maker status (staff vs. manager). Subjects were randomly assigned to each condition. Both factors were manipulated between-subjects; therefore, therewas an experimental session for each condition. Each session consisted of 5 rounds. Table 2 illustrates the experimental design and predicted directions of the mean responses.

|

|

|

5. Results

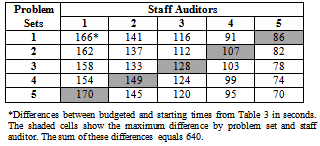

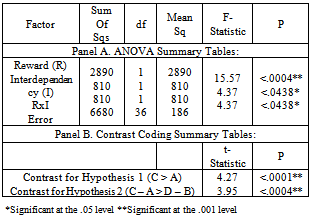

- For each round, we totalled the differences in starting and budgeted times for the subjects in each group. For both hypotheses, we measured the dependent variable by the average total group difference between starting and budgeted times. The higher the difference, the more efficiently staff auditors were scheduled to audit areas. The maximum total difference was 640 seconds and the minimum was 560 seconds. The first hypothesis states that managers in cooperative groups schedule staff auditors more efficiently than do managers in competitive groups. Table 5 reports the average total group difference between starting and budgeted times. Under the cooperative reward structure, managers scheduled staff auditors more efficiently than under the competitive reward structure. Under the cooperative scheme, the average total group difference was 634 seconds, while under the competitive scheme, it was 608 seconds. Table 6, panel B presents a linear contrast showing that this difference is significant (p <.01).

|

|

| Figure 2. Means of Group Scheduling Efficiency |

6. Conclusions

- Group decision making plays a central role in public accounting firms. Despite its importance, little research on judgment and decision-making considers the multi-person component of the auditing environment, particularly on the interaction of type of group process and type of task. Our study contributes to the literature on multi-auditor decision making by investigating the interaction of two types of group processes (cooperative and competitive) and two types of task interdependency (high and low) on performance in scheduling staff auditors to audit areas. The results support our first hypothesis that managers in cooperative groups schedule staff auditors more efficiently than do managers in competitive groups. This implies that public accounting firms should provide their employees with cooperative rewards. However, the hierarchical structure and promotion-based practices of accounting firms reflect competitive rather than cooperative rewards. This implies that the benefits of competitive reward structures outweigh the cost of reduced scheduling efficiency ([40]). Two such benefits of competitive rewards include more efficient risk sharing and motivation (e.g.[41],[42]). Still, firms should understand the costs of using competitive rewards, which would include the less efficient scheduling of employees. We find support for our second hypothesis that the difference between scheduling efficiency under competitive and cooperative reward structures is greater when managers, rather than staff auditors, schedule audit areas. Specifically, the scheduling efficiency of managers is the same as staff auditors under cooperative reward structures and lower than staff auditors under competitive incentives. Support for this hypothesis implies that public accounting firms improve their overall performance by having staff auditors schedule themselves to audit engagements. Of course, we do not offer this as a definitive prescription or description since we examine only subset of the variables that affects the procedures a firm follows in completing its schedules. However, the results of this paper do suggest that staff auditors should, in some fashion, be involved in the scheduling process. In sum, our study provides support for the interaction of group processes and task interdependency on the efficiency of scheduling staff auditors to audit areas. The findings make contributions to both the literatures on multi-auditor decision making and on the interactive effects of group processes and task interdependency. Our study responds to[1] in that we investigate the interaction of two types of group processes (cooperative and competitive) and two types of task (high and low interdependency). In addition, in demonstrating the interaction between competitive and cooperative groups and task interdependency, we investigate the task of scheduling, which is important in itself. Our study also contributes to the literature by generalizing the interactive effects of group processes and task interdependency to a practical setting. To our knowledge, this represents the first study that takes as a given the task interdependency that exists in an organization as opposed to inducing task interdependency as an experimental manipulation. Care must be taken in interpreting and generalizing our study’s results. Given that we used a controlled experiment with a small sample size, our study is subject to the usual well-documented limitations associated with experimental research under such conditions. Our study should be viewed as exploratory. As such we call for future research to replicate and/or extend our study by obtaining larger samples and by using auditors in addition to, or in place of, students as test subjects. Additionally it would be informative to vary the experimental tasks such that they are more representative of the tasks that professional auditors would realistically be scheduled to complete. Future research could also incorporate other aspects of performance not included in our study. The findings suggest that public accounting firms interested in cost-saving efficiencies should allow auditors to self-schedule, at least on a trial basis, in order to determine whether such changes will in fact lead to reduced audit costs in the field.Given our results showing the benefits of self-scheduling, this future research might ask why public accounting firms do not allow auditors to self-schedule to audit areas. Our results suggest that enabling auditors to self-schedule reduces total audit time in practice. However, it is possible that enabling self-scheduling leads to dysfunctional behavior that is not identified in a controlled experiment. In addition, even if self-scheduling leads to reduced costs for client audits, firm-wide problems might arise. For example, self-scheduling might incentivize auditors to choose the audit areas in which they are most proficient, failing to learn about other audit areas. Perhaps self-scheduling leads to too much specialization of auditors. Such potential problems would need to be investigated in future research with more realistic experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank Mark Cannice for his comments on a previous draft of this paper. The authors would also like to thank Mike Becker, Steve Huxley and Joel Oberstone for helpful discussions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML