-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

p-ISSN: 2169-9607 e-ISSN: 2169-9666

2012; 2(5): 65-73

doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20120205.01

Shared Services Centre for Client Convenience: A New Perspective in Public Service Delivery. (Evidence from One-Corner-Stock-Shop in Niger State, Nigeria)

Musa Muhammad Lawal, Nura Abubakar Allumi

Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, 840244, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Nura Abubakar Allumi, Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, 840244, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Shared Services Centre (SSC) is one of the tenets of Digital-Era Governance (DEG) that integrates information systems for organizations to easily interact with each other sharing activities, processes, services, knowledge, technological infrastructure and best practices without necessarily affecting their autonomy. The Nigeria public sector is yet to make parallel with this basic tenets of DEG in it bureaucratic processes which have advisedly affected it level of service delivery. This paper intends to analyze empirically the motives and other management issues of establishing Niger State One-Corner-Stock-Shop (OCSS). The paper however employed a standalone qualitative case study. The findings revealed that the OCSS is still work in progress into ICT’s potentials that for now creates clients conveniences, enable sustainable ICT infrastructure and enhanced mutual interactions for participating organizations.

Keywords: Shared Services Centre, Digital-Era Governance, One-Corner-Stock-Shop, Niger state

Cite this paper: Musa Muhammad Lawal, Nura Abubakar Allumi, "Shared Services Centre for Client Convenience: A New Perspective in Public Service Delivery. (Evidence from One-Corner-Stock-Shop in Niger State, Nigeria)", Human Resource Management Research, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 65-73. doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20120205.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Dunleavy[1], asserts that we are in a ‘digital-era governance’(DEG), characterised by using ICT to reintegrate services, design services around people’s needs, and enable citizens to access services online. In spite of this, there has been persistent global outcry on the declining level of public service delivery. With shrinking revenues of public organizations, clients savvy as a result of globalization and growing service demands, organizations are joining forces to provide enhanced services to their clients. Shared Services (SS) are agreements between organizations to combine resources and provide excellent services to their clients. The idea behind SS is to share some common (not core) elements in their organizations. One of the most critical challenges of the SS paradigm is how to integrate for instance routine administrative activities such as information-data systems to a SSC in such a way that different organizations can suitably interact with each other by sharing activities, processes services etc. This integration essentially create pull of economies of scale such as reducing time dedicated to bureaucratic processes by clients, increases quality of services delivery, allows sharing of knowledge, information and best practices.OCSS is an SSC that provides the fundamental drivers for shaping public service delivery and organisational development in this digital era. These drivers can be summed up as – disintermediation – which means the stripping out, slimming down or simplification of intermediaries (duplication) in the process of delivering public services. Disintermediation achieves ‘joining-up’ by significantly and visibly reducing the bureaucratic complexity of the public institutions which citizens are confronted with in trying to access public services (Dunleavy,[1]). However, establishing an SSC requires considerable involvement of ICT resources that can be unsustainable in terms of cost and maintenance especially for small public organizations. Requisite technologies that support an SSC are fundamental to develop a general architecture that integrates all information systems of each organization intoone-single-folder designed to facilitate unified clients service delivery.Overall cost reduction was the initial rationale for implementing SSC, but high-performance governments in terms of service delivery now takes a more value-oriented precedence. In a bit to leverage the full potentials of SS as an opportunity to improve public-sector value and transform citizen-centered service delivery, adopting a true SSC operating model requires a dramatic transformation and corporate culture change that address both administrative processes, policies, organizational structure, human resources management and technology. However, many organizations address a few of these components when trying to set up an SSC in achieving economic of scales. Unless all of these components are addressed holistically, the benefits of SSC will not be attained.Therefore, this research aims at critically examining how practice really matches theory on the concept of SS and SSC. Our goal is to identify the drivers; critical success factors, benefits and challenges of SSC with particular reference to the Niger State OCSS as an SSC for acquiring the New National Vehicle Plate Number and Enhanced Drivers License. To ascertain if really this initiatives of OCSS can be said to be a true SSC.

2. Issue

- Organizations that branded themselves as SSC begin with a limited scope of services essentially related to a specific department or function. These limited scope organizations sometimes do not go beyond their past bureaucratic complexity and do not also demonstrate many of the key attributes found in a successful multi-functional SSC operating model. This raises the question as to whether such an operation is a true “shared services model” or merely a centralized functional organization. Despite the benefits of SSC, many public organizations in nations like Nigeria have been slow towards moving to a SSC infrastructure, simply because there is little or no much attention given to this area by the government. Again, no one-fit-all approach to having a successful SSC. These have lead to some confusion as to how to go about true SSC. There appears to be little researches or published materials on the issue of SSC arrangements in general and in the public sector in particular leading to no or little experience of this arrangement. This research examines what an SSC infrastructure is, how to consider evolving one, and best practices for launching such an initiative to avoid a mishmash of initiatives and achieve maximum economies of scale within the public sector.

2.1. Methodology

- A qualitative stand alone case study approach is employed. Case study is preferred because the story is unique and provides context to other data (such as outcome data), offering a more complete picture of what transpired in Niger state one-corner-stock-shop, Holetzky,[2]. At first, the researchers introduced the structured interview to standardize the interview as much as possible and thus as Gubrium and Holstei[3] argued reduce the effect that the interviewer's personal approach or biases may have upon the result. The question format/structure was Open-ended; Closed-ended with ordered response choices; and closed-ended with unordered response choices and partially closed-ended. The second level of interview was embarked upon to be able to effectively situate what has been captured from other employees in the study area, the senior personnel were approached and the style of interviewing was semi structured form. Nature of questioning was flexible. The last stage of interviewing adopted was the unstructured interview. Here the researchers placed this as the last category and clarified some issues with the chief executive in the results obtained from the two sets of people. Hermeneutical Analysis (Hermeneutics) was employed. This method integrates the constructs of dialogue, the hermeneutic circle, and the fusion of horizons to define a process for data analysis (Ajjawi & Higgs,[4].As far as this research is concerned however, the reliability and validity have been established through two main different means of Standard and Verification. To be able to adequately verify the rigor, ensure methodological coherence, sampling sufficiency, developing a dynamic relationship between sampling, data collection and analysis, Meadows & Morse,[5].

3. Related Literature

- A review of related literature on SS in the public sector shows that there is very little research or discussions on SS arrangements for public sector and, specifically, the practices of SS in developing countries as Nigeria. Indeed, there appears to be little experience of these arrangements. SS as a concept can take many forms and terms describing the arrangements of SSC such as: Inter-local Agreements, Shared Services, Service Transfers, Government Partnerships, Contracts with Government, Joining- Up and many other variants. This accounts for the existence of numerous partnership arrangements between and among public entities. These partnerships platforms have been previously treated (Ghash et al,[6]; NAO,[7]; Audit Commission,[8]). The most popular term is “Shared Services,” and that is the term adopted throughout this research work.

3.1. Evolution of Shared Services

- Since the 1980s, when the concept of SS first began to emerge, a number of trends have converged to give it added momentum. Successive waves of advance approaches like Business Process Reengineering and Six Sigma fixed attention on getting more out of processes, Spoeher, et al[9]. Initially, SS was an organizational and management tool first utilized by the private sector and later adopted by the public sector. In the business sector, SSC work as distinct units within individual organizations which then unite to provide services to a group of organizations (Spoeher et al,[9]). By the mid-1990’s, SS was introduced to the public sector as well. Public sector SS can be thought of as an extension of the Reinventing Government Movement, as it emphasis on less wastefulness and an entrepreneurial approach to public management. SS in the public sector occurs when two or more government entities join together to provide a service for all the clients within their jurisdiction, Vazquez - Cortes,[10]. Within the context of the public sector, there are usually two types of services. One is corporate services known as back-office services which are generally administrative and transactional services and core services which are fundamental to each organization (Spoeher et al,[9]). An SSC normally, treats back-office services which are routine administrative schedules. While transactional services are left to the parents organizations to handle.

3.2. Rational

- As Lipsky[11] argue, resources in public sector will perpetually be inadequate because even when services and resources are constantly expanded, the demand for services will always exceed the supply. Even if the number of people demanding for services did not increase (most of the time it does), the demand for quality of service will still increase. Public institutions must make important choices in determining how proper services will be provided not only according to the funds available but in line with current cost saving trends. In today’s digital world, we cannot afford to consume resources in doing things wastefully, less effectively or less cheaply in the public sector than it is possible to do analogous tasks in both the private sector and the civil society. Therefore, it follows from this argument that the practice of SS is increasingly becoming popular in the public sector, and it’s a trend that’s expected to continue to offer a logical solution. SSC reduces redundant effort within an organization. If the same operations are occurring in several divisions within an organization, it’s more efficient to designate one source as the provider of that same work across all divisions. By sharing the services provided by that one source, the organization benefits from economies of scale, improved efficiency, lower costs, better quality and this translate into client benefits. Most often, it’s administrative/routine type of work that’s shared especially data capturing and processing.

3.3. Shared Service Centers

- It becomes easier comprehending what an SSC is from the basic understanding of SS. Queensland Treasury[12], classifies SSC as involving ‘multiple agencies sharing common corporate services through a dedicated Shared Service Provider’ that is SSC. SSC provides the platform for translating the SS tenets into reality. Through the SSC, agencies develop partnership approach to provide services with responsibilities, accountabilities and authority clearly understood. As such agencies can purchase services based on agreed cost and quality parameters. Moreover, participation in the SSC platform, ideally facilitates a process of continuous innovation and improvement in the quality and cost effectiveness of services. As Frost[13] maintained, SSC can make services more accessible to service-users and improve internal professional relationships and ways of working. Services are integrated, centrally planned and coordinated to focus on one or more particular objectives. Services delivered in such a round as an OCSS can enable a better response to the client’s needs, creating convenient and better value for money.

3.4. Outsourcing

- We can further distinguish between “outsourcing” and SSC, the former represents services legally provided by an independent third party that is not part of the sharing units or organizations, while the latter is a proper function (SSC) within a “corporate group”. Outsourcing to a third party, provides who takes full responsibility for the management and operation of services. The idea of SSC is to gain from the investments in the domain of e-government by sharing common elements presented in a single administration. An SSC should be managed like third-party vendor, tailoring their IT-services to the requirements of their customers at a cost that the customers are willing to pay, Schmidt,[14].

3.5. Prior to Sharing

- Sharing is but one option to be considered when seeking for SSC’s economies of scale. Sharing works best when organizations operate within similar line of functions, share common processes and have alignment of organizational values and goals. It is important to recognize that sharing is “first and foremost a human and political challenge”. The term sharing implies surrendering of some power, autonomy, resources, people and control; whilst retaining responsibility and accountability. The key issues to address from the onset are the building of trust and a shared vision between and among shared organizations. Therefore, creating SSC models requires a new style of leadership skilled at building collaborative capacity both within organizations and with strategic partners. As Bland[15] observed, the first step is for the approval of Top Management of each organization for the need to consider which SS model of collaboration best suits their needs. The most essential drivers of moving to an SSC environment are to assist the consolidation of various hitherto separate applications operated by different organizations into a single-line process platform. It may not be possible to switch to a single system overnight. The primary focus of SSC has been the concentration of back-office orientated services that are repetitive and are much the same for each unit. Generally, these types of services included in a SSC include financial services including accounts payable and accounts receivable; procurement; human resources including registry, payroll; property and facilities management; and information technology operations.

3.6. A True Shared Services Center

- This highlights the important characteristics of a successful or true SSC widely recognised by Chartered Institute of Public Finance, Maclean,[16]; UN,[17] as being:• There must be a clear, well define common vision, with leadership will and drive from the top management of the each organisation (including sometimes elected members as it relates to public organizations);• Combining a SS project with business process efficiencies, redesigning services to streamline them prior to consolidation;• Commitment to significant change and standardisation across participating organisations;• Clear understanding and benchmarking of the positions, duties and responsibilities prior to change;• A roadmap defining the process of transformation, including the change management needs and governance arrangements required for operation;• The institutionalization of these basic administrative tenets accountability, transparency and effective project management control.Others include: Agree on a workable model – decision-making will need to be relatively easy to ensure the initiative gets off the ground, but it will be difficult for stakeholders to agree to any loss of control and accountability. Ensure senior commitment to Shared Services – they are strategic initiatives and will need support from the very top in order to be successful. Understand current baselines of performance – they will play an essential role in calculating whether the SS is more efficient than the previous way of working. They can also feed into objectives and relevant targets in service level agreement. Clarify why the organization wants to implement Shared Services – this will inform which model to adopt. For example, if improving organization processes is a major driver, it may be worth involving a private sector partner with specialist expertise in this area. Conduct a rigorous due diligence exercise – it is essential to know exactly where each partner stands in terms of existing contracts, exit provisions and intellectual property rights in order to prevent any nasty surprises further down the line. Agree on whether to move to a ‘Greenfield Site’ – it may be easier to move to a different office and make a fresh start than to continue working from existing locations. This can be particularly beneficial if the arrangement involves multiple organizations, as none of the staff will be on “home territory”.Identify the organization’s own capacity and appetite for change – if this is low it might be easier to piggy-back on someone else’s initiative. Understand the cost and possible funding options – some participants could be keener to put money in than others and private sector partners might agree to help with up-front investment Agree on the amount of risk each organization is prepared to carry – this will play an important role in contract negotiations and feed into the organizations case process. Identify any potential staff opposition – then it can be dealt with at an early stage. Any solution that may result in redundancies, relocation or changes in employment terms and conditions is likely to be controversial. Remember that other Organizations may wish to join at a later date – this will affect the governance model and technical architecture. Remember the rules – these may mean that all legal and cooperate instruments that established organizations as legal entities that can sue and be sued must be considered. This is something that also makes the initial scoping exercise even more important. Agree on whether the Shared Service could generate Income – this will affect discussions about shared investment, risk and reward. The above listed points will help stakeholders decide on a preferred type of shared services model.

3.7. The Major Drivers of a Shared Services Center

- Model Components: TechnologyTechnology serves as prime mover of any SSC as set out in the PA report[18], supported by the MSP blueprint providing the vehicle to ensure a clear specification of any technology components required to support major change and access programmes. It becomes paramount that the technology component of an SSC must address both the underlying infrastructure and individual systems-needs components that support the entire vision and strategy of establishing the SSC. This extends across, and encompasses, those areas covered by channel strategy, face to face data capturing connectivity, web, telephone (e.g. contact centre setup) that support front and back office systems and infrastructure requirements. The technology components need to clearly relate their purpose to the organizations objectives and customer strategy, set out in the model agreements Kaila et al,[19]. This ensures the right selection of technology, which should then be configured and deployed to meet the needs of the client centric processes.Model Components: Information (Data and Analysis)The information component aptly suits the OCSS that basically captures data from clients as an integrated data bank where a large amount of activity in the field of client insight is integrated to form a national data base that reduces duplications, multiple registrations, network services etc. The need for data and analysis of data is critical to all aspects of client contact data base. This component reflects service and storage design through channel strategy and process design, to feedback mechanism and continuous improvement. It ensures high quality, accurate client information – both on clients themselves, and the way they interact with the organization – as essential to be adequately stored, analyzed, distributed and applied, Thompson,[20]. Meanwhile, Nelson et al[21] identify three types of data for effective management of client information – descriptive data, relationship data and contextual data. To achieve a well functional SSC it becomes very imperative for the quality of data to be addressed squarely, with poor quality information identified as a significant factor to SSC failure, and poor return on investment. “Only when a foundation of good data has been built will a One-Stock-Shop find it easy for subsequent investments to generate acceptable return”. Nelson & Kirkby,[22]. The purposes for which data is to be used (for strategic planning or direct service provision to clients) must be driven, not only by the technological products or appropriate data software available, but by other key components like the SSC strategy, client’s strategy and the proposed vision and experience.Other Key DriversBesides the above two major drivers, Accenture[23] provides some other key drivers of SSC as:• Consolidating administrative functions into a stand-alone organizational entity, whose only mission is to provide administrative functions efficiently and effectively;• Redesigning standardized end-to-end processes around best practices, utilizing enabling technology.• Requiring a dramatic redesign or transformation of the organizational structure and workforce.• Elevating the importance of administrative tasks to the highest management levels so they take on “front office” importance.• Building a high-performance culture with a strong focus on service excellence (rather than solely a cost focus) and continuous improvement.• Clearly defining responsibilities for both customer and service provider via service-level agreements, key performance indicators and a comprehensive service management framework.• Typically operating in a low-cost, high-skill area.

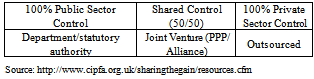

3.8. Shared Services Centre Models

- SSC models range from informal cooperation (casual understanding) through a series of iterations to full integration of services (i.e. merger). Various collaborative route maps have been developed to help steer management discussion. From a public sector perspective reflecting the UK Cabinet Office Central Government Shared Service, Making Government Work Better document.20 This document provides guidance to clients and providers of SS by categorising the delivery options into three categories: 100 per cent public sector control, joint control (or 50/50) and 100 per cent private sector controlled.Using the UK model as a guide, we can simply categorised SSC models into three:

The SSC models are receiving most attention include the followings:In De-Centralized Organizations: Each unit has its own support service tailored exactly to individual requirements. These previously distributed support services are now consolidated while forming SSC. The aim is to avoid duplication of work and to achieve synergies, Berger,[24]. Absolutely Engaged in Support Services; these are processes that support core processes of the organization. Goold et al.,[25], this further differentiate between services for transaction-oriented, complex and knowledge-based processes. Transaction-oriented processes are mainly processes that share a high degree of commonality or standardization, feature few interfaces with other processes and technologies, entail low financial/business risk, depend only to a small degree on outside clients, and show a high potential for automation, Shah,[26]. Typical processes are wage accounting, bookkeeping or operating a computer centre. Characteristic processes in the area of knowledge-based processes are, inter alia, administrative analysis, staff training, and development of applications or even real estate management, Quinn et al.,[27].Alignment with External Competitors: these platforms of SSC align themselves with external competitors (Young,[28]. To enhance competitiveness, SSC build strategic knowledge such as information about competitors in the external market, analyzing its own strengths and weaknesses, and pricing benchmarks. Through these processes SSC can confirm their competitiveness to internal clients and explain deviations (Quinn et al.,[27].Independent Organization/Partly Autonomous: Mostly this explicitly emphasizes the independent organizational form of a SSC as a unit clearly separate from other units, with its own responsibilities and its own management. Frequently the term “partly autonomous” is used Bergeron, [24], which is meant to signal that the SSC are managed like separate unit but still highly dependent on the parent company. Thus the SSC typically belongs 100% to the organization which at the same time is its main client. A Co-Location Model: consists of a numbers of organisations that share a common premises and common resources and facilities such as secretarial services, photocopying, joint insurance etc. On its own, a co-location model does not necessarily entail the adoption of SS arrangements such as book-keeping. However, this model nevertheless has the potential to facilitate these kinds of arrangements. Another variation of the co-location model is described by Earles et al[29] in relation to a trial of a SSC it consisted of four family services organizations that collaborated to form a SS function. In this case, the SS arrangement involved co-governance (where one member from each of the four co-governing agencies formed the SS Management Committee) and co-location (where members from each organization were co-located in other organizations participating in the SS arrangement) with the primary purposes of this approach related to fostering collective identity and learning across the collaborating agencies. More fundamentally, this model placed importance on the development of effective relationships between the members of the different agencies.Service-Oriented Focus on Internal Clients: An SSC aims at optimizing the internal client experience, focusing on service output—a defined functionality with contracted quality levels and an agreed price including penalties, Young, [28]. This approach enables the central department to act clearly on behalf of internal clients, a relationship which exhibits monopoly-like behavior, Bergeron,[24]. These traditional departments were typically focused on improving technologies used for producing the services and less on improving the actual service output. An amalgamation or merger model: wherebyorganizations in a similar field of service amalgamate with each other to form a single larger organization and, as a result, consolidate and streamline their administrative functions. Recently, this brand is more common to commercial banks in Nigeria.

The SSC models are receiving most attention include the followings:In De-Centralized Organizations: Each unit has its own support service tailored exactly to individual requirements. These previously distributed support services are now consolidated while forming SSC. The aim is to avoid duplication of work and to achieve synergies, Berger,[24]. Absolutely Engaged in Support Services; these are processes that support core processes of the organization. Goold et al.,[25], this further differentiate between services for transaction-oriented, complex and knowledge-based processes. Transaction-oriented processes are mainly processes that share a high degree of commonality or standardization, feature few interfaces with other processes and technologies, entail low financial/business risk, depend only to a small degree on outside clients, and show a high potential for automation, Shah,[26]. Typical processes are wage accounting, bookkeeping or operating a computer centre. Characteristic processes in the area of knowledge-based processes are, inter alia, administrative analysis, staff training, and development of applications or even real estate management, Quinn et al.,[27].Alignment with External Competitors: these platforms of SSC align themselves with external competitors (Young,[28]. To enhance competitiveness, SSC build strategic knowledge such as information about competitors in the external market, analyzing its own strengths and weaknesses, and pricing benchmarks. Through these processes SSC can confirm their competitiveness to internal clients and explain deviations (Quinn et al.,[27].Independent Organization/Partly Autonomous: Mostly this explicitly emphasizes the independent organizational form of a SSC as a unit clearly separate from other units, with its own responsibilities and its own management. Frequently the term “partly autonomous” is used Bergeron, [24], which is meant to signal that the SSC are managed like separate unit but still highly dependent on the parent company. Thus the SSC typically belongs 100% to the organization which at the same time is its main client. A Co-Location Model: consists of a numbers of organisations that share a common premises and common resources and facilities such as secretarial services, photocopying, joint insurance etc. On its own, a co-location model does not necessarily entail the adoption of SS arrangements such as book-keeping. However, this model nevertheless has the potential to facilitate these kinds of arrangements. Another variation of the co-location model is described by Earles et al[29] in relation to a trial of a SSC it consisted of four family services organizations that collaborated to form a SS function. In this case, the SS arrangement involved co-governance (where one member from each of the four co-governing agencies formed the SS Management Committee) and co-location (where members from each organization were co-located in other organizations participating in the SS arrangement) with the primary purposes of this approach related to fostering collective identity and learning across the collaborating agencies. More fundamentally, this model placed importance on the development of effective relationships between the members of the different agencies.Service-Oriented Focus on Internal Clients: An SSC aims at optimizing the internal client experience, focusing on service output—a defined functionality with contracted quality levels and an agreed price including penalties, Young, [28]. This approach enables the central department to act clearly on behalf of internal clients, a relationship which exhibits monopoly-like behavior, Bergeron,[24]. These traditional departments were typically focused on improving technologies used for producing the services and less on improving the actual service output. An amalgamation or merger model: wherebyorganizations in a similar field of service amalgamate with each other to form a single larger organization and, as a result, consolidate and streamline their administrative functions. Recently, this brand is more common to commercial banks in Nigeria. 3.9. Which of these Models Best Fit the One-Corner-Stock-Shop?

- The above mentioned models of SSC represent some (not all) of the types of SSC, it becomes critical to ask which of the above modals best fit or describes the research case study? As observed earlier on, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach of SSC. Couple with the issue of identifying a “true SSC.” The Co-Location Model partially fits to some extent the One-Corner-Stock-Shop initiatives with these features:Common Premises Co-location provides a new hosting avenue established separately for all the participating units distinct from their parent units.A co-location model does not necessarily entails the adoption of SS basically from the observed method of operations (by the researchers) of theOne-Corner-Stock-Shop initiatives, because each of the participating units is physically represented by an agent assigned to capture data of their clients for their parent organization. While a true SSC is an independent entity that provides agreed services to the shared organizations. The One-Corner-Stock-Shop aptly reflects the model described by Earles et al[29] the One-Corner-Stock-Shop Initiatives is with the primary purpose of fostering collective identity and learning across the collaborating agencies. More fundamentally, this model placed importance on the development of effective relationships between the members of the different agencies. And creating that One-stop convenient for the clients for which previously, a client have to separately deal with the four principal actors to capture his data. But for now, these separate principal actors are each presented by an agent in the new established SSC. In 2003 the state office of Meals on Wheels offered to take on all “paperwork” for its 136 local branches, thus allowing them to focus more on service delivery – that is, the state office would in effect become a shared service provider for all local branches. Previously, each hospital was using different systems and operating as a stand-alone entity. There are now a common chart of accounts and a common system across the group of hospitals providing an improved set of accounts, common purchasing contracts and a consolidated capacity to negotiate with suppliers and funding bodies whereby a peak body within a particular sector or industry provides a range of services for its members in return for a membership fee or a subscription fee or a combination of both which brought together a range of previously separate Uniting Church welfare services under the one umbrella organization.

3.10. Economies of Scale of Shared Services and Public Service Efficiencies

- SS have been explored and implemented with mix results as notable successes, abandoned and unsuccessful projects providing evidence from which to learn. This interest has been reflected in the wider world, leading to a range of research that helps identify the way in which SS can be approached, given the complex range of issues associated. Benefits realization, a report by KM Management Consulting KMCC,[30] proposed five major benefits of SS arrangements, Dollery et al.,[31].Scale economies• Reduction of costs as a main goal: The majority of authors include the goal “cost reduction” explicitly in their definition. Several surveys revealed that cost-cutting is a primary motivator for implementing SS, Ulbrich,[32]. Average savings of 25% – 30% are not unusual, Quinn et al.,[31], and MPC [33], achieving lower costs by making use of economies of scale.• Leveraging of technology investments to achieve cost savings and improved service delivery• Standardisation, consistency and continuousimprovement of process to provide improved service provision• Achievement of a client service focus• Greater concentration of strategic outcomes• Consolidation of processes within the group in order to reduce redundanciesAll these allow to continuously improve the “services standard” and to reach a low level of bureaucracy connected with shared functions.

3.11. Challenges of Shared Services

- The New Local Government Network, a leading UK think tank on local and public governance, notes on its website (.nlgn.org.uk) that: The scale and scope of SS remains extremely limited in terms of political, managerial, geographic and professional protectionism having too often impeded on the smooth running of SSC and led to their untimely demise. GTI [34] in an overview of SSC of public organizations identified a number of inhibitors that includes: • Resistance to sharing control with another authority. • An absence of expertise to manned a true SSC.• The cost of the initial investment on ICT infrastructure, human resources, etc is usually very high. • Attitudinal and career obstacles, linked to individuals' careers as it relates to the risks of reducing headcount. • A desire by top managers to maintain self-determination over front-line services and back-office support functions.

3.11.1. Five (5) Quick Steps to Acquiring the new Number Plate

- 1. Applicant completes online registration (MVA01) form at www.nvisng.org, prints completed form and attach all relevant vehicle documents and proceeds to SBIR/MLA (State Board of Internal Revenue/Motor Licensing Authority) office.2. Pays for vehicle number plate at SBIR/MLA and is assigned a number plate.3. Applicant takes his/her vehicle to VIO for physical inspection and is issued a Road worthiness certificate, if VIO is satisfied with the condition of the vehicle.4. Applicant then goes to Road safety for the verification of documents provided. The verified document are: Driver’s License, Insurance Policy Number, Means of Identification, Proof of Address (e.g. Utility Bill)Applicant returns to SBIR/MLA, where his/her Proof of Ownership Certificate (POC) number will be printed. Then the Proof of Ownership Certificate, his/her Vehicle Number Plate and Vehicle Identification Tag (VIT), is released to him/her.One-Corner-Stock-ShopThe principal actors of One-Corner-Stock-Shop are the Niger State Board of Internal Revenue, Federal Road Safety Commission, Vehicle Inspection Office and Vehicle (Motor) Insurance Company; each represented by an agent/officer. Essentially, the process started with the stoppage of the former manual vehicle registration in March 2011. But the Niger State One Corner Stock Shop formally commenced in December 2011 for the issuance of the New National Vehicle Plate Number and enhanced Driver’s License/ National Uniform Licensing Scheme. The One Corner Stock Shop is an internet-data base connectivity logistics provided by Niger State Government located at the premises of State Board of Internal Revenue.The Manual Vehicle Registration ProcessThe whole process was carried out manually by the four principal partners.The FRSC print out vehicle plate numbers for each state of the federation.Each state procures these plate numbers for the use of their motorists through Motor License authorityOffice/Department under the Board of Internal Revenue for allocation of plate numbers and vehicle papers.Also the Vehicle Insurance Policy was done manually with no guaranty of policy.This manual process was pruned to abuse as a vehicle can obtained more than one plate number.The New E-Vehicle Registration ProcessThe VIO starts the process with vehicle examination, if satisfied a certificate of recommendation is forwarded to the Vehicle License for the vehicle to be register through Policy Number for the issuance of road worthiness at the end of the e-vehicle registration process.All entering papers which include: Custom Papers, Purchasing receipt and etc, with one form of National Identity- such as Federal Republic of Nigeria National Identity Card, Drivers License and International Passport. The License Authority Officer examines all these papers for certification of their originality.A temporary file is now opened for the vehicle, a form with a full data of the vehicle owner and details of the vehicle. Allocation of vehicle plate numberThe temporary file is passed to the representative of the FRSC, to confirm the genuineness of the plate number at their central data base in Abuja. This temporary file moves to the Motor license office for the issuance of all relevant papers and prove of ownership certification. This file moves to the Motor Insurance Company agent for a Third Party Insurance Policy.At this stage the file finally goes back to the VIO for Certificate of Road Worthiness. Similarly, on-line payment for driver’s license has been introduced while the FRSC has taken initial step to computerize about 212 duty rooms located in its formations spread across the country, to further build a digital-enabled capacity to administer and collate data bordering on traffic offenders.Additional modalities for the proposed new drivers’ license, which has been endorsed by the Joint Tax Board include, the introduction of new measures for processing and production of drivers license such as, the sponsorship of fresh applicants by FRSC accredited driving schools, practical and theory driving tests and retests to be conducted by the Vehicle Inspection Office and the FRSC, on-line payment by successful applicants which, will be followed by physical capture of applicant’s biometrics and issuance of a temporary paper driving license at the one-step shop which will accommodate the FRSC, VIO and the Motor Licensing Authority valid for a month before production of the drivers’ license at the central print farm at the FRSC. The issuing desk of the Motor Licensing Authority, located at the one-stop-shop will further undertake delivery of produced drivers’ license to owners as part of the measures to stamp out parallel production, ensure reduction in processing time and also build a reliable database on the drivers’ license.Details of the proposed new drivers’ license indicate improved security features such as laser perforator, ghost portrait, over lapping data, altered font, variable micro script and split fountain printing.For the number plate, improved security features include directional visible water marks, depressed flange border of plate, issuance tied to vehicle owner, font size change from 5 ½’’ x 12’’ to 6’’ x 12’’, bolder serial font, reprinting of crest on reflective sheeting in addition to the display of number plate expiry date on the top right corner.

4. Data Analysis and Results

- The interviews were conducted at the convenient time for the respondents to make them feel relaxed in answering the questions. In fact 66 respondents of our 80 targeted respondents cooperated. Below in tables 1 and 2 are the summary of the key questions conveyed to the interviewees.The table above shows that 46 respondents out of the 66 interviewed (69%) believe strongly that SSC is good for them as individuals and for the state as a whole and the remaining 20 (31%) have a contrary opinion about that.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

4.1. Discussions

- We present here the results of the interview. We begin with codification of concepts. Using this we then look at themes of the codified concepts and apply them to interpret how SSC (one corner stock shop in Niger state) impacts service delivery, whether SSC should continue, The interpretations will be used to describe the selected case study area. We considered four questions that are very central to the research and the results of the interview on those questions discussed. Interview concepts that had been coded are Shared services center and service delivery quality was coded as SSC and SDQ respectively and continuity was coded as CNTY. We grouped the codes, across all interviews.We found that these numeric results (in tables 1& 2) show the dominant topics in the interviews but are insufficient indicators to conclude that one corner stock shop has really impacted the public because it is still an ongoing activity in ICT.Numerous relationships between codes emerged through our Generic Relational Coding. Here are some of the codes that are the most popular.The first relationship that was popular was the relationship between

opinions

opinions of the objective behind SSC and

of the objective behind SSC and  Good vs. Bad

Good vs. Bad regarding its overall assessment. Our respondents explained their ideas according to some biased definition of theirs. The relationship,

regarding its overall assessment. Our respondents explained their ideas according to some biased definition of theirs. The relationship,  opinions

opinions &

&  Good vs. Bad

Good vs. Bad informs that respondents were very biased about SSC, which pose another challenging task of wanting to know whether it is enough to conclude through individuals’ subjective evaluations on whether SSC is good or bad. This is perhaps evidenced in the second relationship that appears stronger than the first one.Second dominant relationship across the interviews was

informs that respondents were very biased about SSC, which pose another challenging task of wanting to know whether it is enough to conclude through individuals’ subjective evaluations on whether SSC is good or bad. This is perhaps evidenced in the second relationship that appears stronger than the first one.Second dominant relationship across the interviews was  Opinions

Opinions &

&  SSC

SSC and the third was

and the third was  Continuity

Continuity &

&  Agree vs. Disagree

Agree vs. Disagree . Through responses gathered from the subjects, we understand that the reason behind some of the respondents disagreed to the continuity option is simply because of bureaucratic bottlenecks not because the SSC is less important. Similarly, another dominant relationship was one between

. Through responses gathered from the subjects, we understand that the reason behind some of the respondents disagreed to the continuity option is simply because of bureaucratic bottlenecks not because the SSC is less important. Similarly, another dominant relationship was one between  Continuity

Continuity and

and  adjustment

adjustment . This relationship was important largely due to the fact that most of our respondents are civil servants who rely heavily on their monthly salary earnings. The following quote by one of the respondents is a fitting example” the procedure is very lengthy and things are not in any way easier especially for us that are not business men” Through quotes such as this, we saw that adjusting the existing procedure in SSC should be given a thought.

. This relationship was important largely due to the fact that most of our respondents are civil servants who rely heavily on their monthly salary earnings. The following quote by one of the respondents is a fitting example” the procedure is very lengthy and things are not in any way easier especially for us that are not business men” Through quotes such as this, we saw that adjusting the existing procedure in SSC should be given a thought.5. Conclusions

- Dismal service, soaring cost and rolls of red tape continue to muddy the reputation of many Government agencies. But the time is right for fresh thinking on how government support services should be organized and managed. Today, public organizations are struggling to improve services while managing cost- trying to achieve better value for money. The practice of shared services is increasingly popular in the public sector, and it’s a trend that’s expected to continue. With escalating pressure on budgets, and governments being expected to provide services more efficiently, the shared services model offers a logical solution.The business model known as shared services reduces redundant effort within an organization. If the same operations are occurring in several divisions within an organization, it’s more efficient to designate one source as the provider of that same work across all divisions. By sharing the services provided by that one source, the organization benefits from economies of scale, improved efficiency, lower costs and better quality. Most often, it’s administrative or back-office work that’s shared. But shared services can also work for e-mail, help desk, software, IT infrastructure and numerous other areas.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML