-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Human Resource Management Research

2012; 2(3): 9-14

doi: 10.5923/j.hrmr.20120203.01

The Astra-Manager Tool: A Method of Measuring Competencies of Micro Firm’s Managers

Elzbieta Talik 1, Mariola Laguna 1, Monika Wawrzenczyk-Kulik 2, Wieslaw Talik 1, Grzegorz Wiacek 3, Graham Vingoe 1, Patrick Huyghe 4

1Institute of Psychology, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, 20-950, Poland

2University of Economics and Innovation, Lublin, 20-209, Poland

3North Devon College, Devon EX31 2BQ, Great Britain

4Syntra West, Brugge 8200, Belgium

Correspondence to: Elzbieta Talik , Institute of Psychology, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, 20-950, Poland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article presents the process of constructing a new method for evaluating the competencies of micro firm’s managers – Astra-Manager. The literature study on competence pointed out the need to construct a multidimensional tool, which assesses the competencies strictly connected with leading a small enterprise (specific competencies) and those referring to other areas of activities (general competencies). The Astra-Manager method was created, which comprises of 75 statements grouped in 12 scales. The psychometrical analyses were carried on the results of 180 micro firm’s managers from six European countries. The reliability of specific scales ranges from .53 to .89. The method identifies competencies gaps and helps to design training for managers.

Keywords: Managerial Competencies, Micro Firms, Assessment, Training

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The main aim of this article is to present the process of constructing the Astra-Manager tool which is a new method for evaluating the competencies of micro firm’s managers–employing not more than 10 people. Unlike the studies on managers in large organizations, there has been very little systematic research on entrepreneurial and managerial competencies in small and micro businesses[1].Entrepreneurship is connected with the creation of something new and valuable, discovering and utilizing new possibilities[2]. It seems important to define the entrepreneur’s characteristics that enable him or her not only to survive in the market, but also to develop and become successful. Hence it is important to assess the major characteristics required to successfully functioning as an entrepreneur and a manager. For this reason the Astra-Manager method was created, which enables the measurement of managerial competencies. This can be the starting point for preparing training that takes into account the training needs of assessed managers. Such competence assessment can influence management practice within a company and initiatives connected with the shaping of professional life.

2. Managerial Competencies

2.1. The Notion of Competencies

- Competencies are the subject of research within several domains of social science, e.g. psychology, management, law, sociology, organisational studies. It is difficult to present a universal definition of competences. Most often it refers to somebody’s knowledge, area of rights, responsibilities and skills. This expression is used in most research to state the effectiveness with which an individual operates in different, complex and changing circumstances, tasks, social roles or situations[3, 4].There are different ways of defining competencies, taking into consideration different aspects of this notion. Most often they are divided into general competencies relating to different areas of life and specific competencies relating to narrower areas such as, occupational or social competences. Other authors distinguish between those competences that concern people and competencies which are specifically job-related[5]. Rankin[6] describes them respectively as behavioural competencies and technical competences. Behavioural notions of competence concentrate on the behaviour, attitudes and skills of individuals achieving high effectiveness in their work[6]. This apprehension of competencies originates in the works of McClelland[3] and his criticism of the use of academic intelligence test and IQ factors as a basic prognostic of future success in professional life. McClelland acknowledged that tests based on the analysis of behaviours distinguishing people achieving best results in specific jobs, would be most valuable[7]. The research was continued through the 1970s by McBer & Company, established by McClelland. They concentrated on the identification of the behaviours which distinguish successful managers. As a result, a general model of managers' competencies was worked out by Boyatzis[8] for the American Management Association. In turn a technical notion of competences was developed in the United Kingdom together with a process of developing vocational standards, started in 1981 by the government agency responsible for public funds dedicated to training[5]. Vocational standards formulated on the basis of functional job analysis[6], define the minimum acceptable level of task performance. The technical notion of competences is connected with the analysis of tasks, skills, and knowledge necessary to their fulfilment. Competences formulated this way formed the basis of certification and process of specific vocational qualification development within National/Scottish Vocational Qualifications and Chartered Management Institute standards[5, 6].The former behavioural concept of competencies based on McClelland works was taken as a basis for new measure development.

2.2. Managerial Competencies of Micro Firm’s Managers

- The competencies important for company management are those characteristics which favour the successful management. The entrepreneurial success is the ability to stay in the market and introduce new products and services[9]. The micro firm’s manager is typically a person who has established the firm by himself, thus can be also treated as an entrepreneur. Researchers try to determine the factors influencing entrepreneurial success list abilities, knowledge and skills as important characteristics of the entrepreneur[10, 11].A manager’s work is composed of many tasks, especially in small and micro companies where a manager has to fulfil many of the responsibilities that in big teams would be divided among employees. Employing only a few people, the firm does not possess a well-developed structure or hierarchy. Therefore in such firms managerial tasks include: the purchase of the right materials, sales, marketing, logistics, finance and administration. Moreover risk taking related to strategic decision making is also included into the managerial activity[9].In addition to specific competencies, connected with successfully fulfilling the tasks of small and micro firm management, the manager also needs some general competencies[12, 13]. They can be useful in many areas of human activities, and are also helpful in management. For example: being open to people, challenges and ideas may be important for the success of the venture[14]. Both types of competencies - general and specific - are personal characteristics, which are possible to change and modify[1], for example through training. They are not as stable as personality characteristics. They can reach different levels for different people and also for the same manager in different moments in time[15]. We can try to measure the level of competences and, if they are insufficient, to recommend some training or other ways to develop them. Training and development is considered one of the factors which may be important to venture creation and success[16]. For this purpose the Astra-Manager method was developed.

3. Creation of the Astra-Manager Method

- As a starting point, a study of the literature on competencies was made which pointed out the necessity to create a multidimensional tool, taking into account both, competencies strictly connected with running small enterprises (specific competencies) and those referring to other areas of managers activities (general competencies).

3.1. The Choice of Statements

- A pool of 99 statements was developed (52 for general competencies and 47 for specific competencies). No reversed statements were used. Aiming at multiple-language tool preparation, the representatives of six countries took part in the development of the statements: Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and United Kingdom. The language during the development stage was English.

3.2. Preparation of National Versions

- Each country team translated the statements into their national language – two translators working independently and the third translator who knew the theoretical assumptions and research methodology supervised the translation and reconciled both versions of the translation. Furthermore national versions were given for back translation into English – according to the commonly used procedure of back translation[17]. After comparing those versions with the original, translations into national languages were accepted as satisfactory. To make the tool more transparent and correct, 2-3 people in each country, evaluated each statement and instruction according to understanding in their national language. Each person read translated text and marked the opaque and difficult to understand areas. All doubts and problems were cleared and the supervisor translator gathered remarks and suggestions for improvement. The teams making translations discussed the remarks and agreed the final version of statements in each country.

3.3. The Participants

- Psychometrical analyses were carried on the sample of 180 managers - 30 people from each country, running small enterprises employing up to 10 people. Entrepreneurs represented mainly trade (45%) and services (45%), only 10% of entrepreneurs sampled represented the production sector. The majority of the group were men (63%), women represented slightly over one third of participants (37%). Most of them live in small towns (53%). The participation of representatives of bigger towns and of villages was smaller (respectively – 29% and 18%). They were between 23 and 70 years old (M = 41.11) and possessed approximately 14.5 years of education.

3.4. The Creation of the Scales

- Before further works were carried out, initial analysis of the results obtained for each statement was made. There was a high skewness in the distribution of answers for some statements, meaning that the majority of sampled managers strongly agreed with their content. Those statements with a value of skewness indicator higher than 1.5 were excluded. The initial pool of 99 statements was decreased by 11 statements. An example of the statement excluded – “It is important for me to be punctual”.The starting point for creation of the scales was to carry out an Exploratory Factor Analysis – EFA, separately for general and specific competencies. As an extraction method of common factors, Principal Factors Method was used. Because the assumption was made that the different dimensions of managerial competencies can be correlated, the Oblimin oblique rotation with Delta equal 0[18, 19] was used.At first 45 statements for general competences were analysed. The validity of factor analysis model choice was formally confirmed by: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin KMO ratio (.69) and by Bartlett’s test of sphericity (approximate chi2 = 2456.33; p < .001). The percentage of total explained variance was the method of determination required and sufficient number of common factors – there were 9 factors with the total explained variance not less than 2%. The value of factor loading above .30 was used as the criteria to include variable into a factor after rotation. Six factors were obtained which explain 32.05% of total variance. The results of factor analysis served to create 6 scales, including 39 statements, which are described later in the text.Separately, factor analysis for 43 statements, referring to specific competencies was carried on. The KMO ratio (.86) and by Bartlett’s test of sphericity (approximate chi2 = 4065.99; p < .001) confirmed the validity of the choice of factor analysis. Three factors were obtained which together explain 41.04% of total variance. As the number of statements at the initial stage was bigger the criteria for inclusion of a variable was higher, with a factor loading variable of higher than .40 being used. The results of factor analysis served as the initial stage to construct scales. Because each of the extracted factors was constructed of respectively 13, 10 and 13 statements it was decided that they would be split into smaller groups, including narrower sets of competencies. Expert opinions were also taken into consideration, for those factors emerging as a result of statistical analysis which did not represent uniform and meaningful whole. The statements included in each factor were evaluated by three competent judges – experts who advise on small firm management on a daily basis. Such procedure seems justified because statements refer to self-evaluation of the skills necessary to deal with tasks relevant to leading economic activity. Each answer can be analysed separately, not necessarily solely as an index for more general characteristics, as happens in general competence analysis. Eventually the measure of specific competences included 36 statements and, as a result of expert’s grouping, 6 scales were constructed (two for each factor).

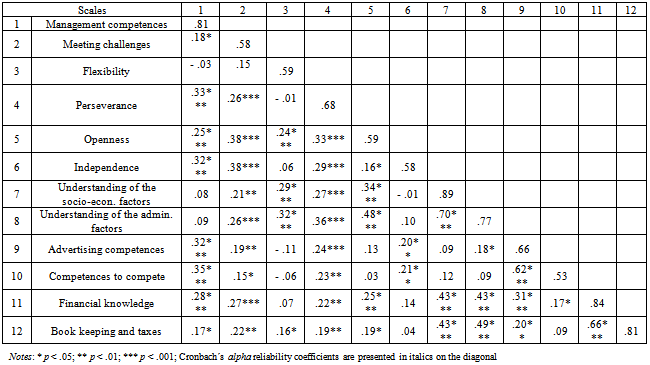

4. Psychometric Properties of Scales

- Eventually the method of measuring the competencies of micro company’s managers – Astra-Manager was created. It includes the following scales:1. Management competencies (15 statements) – basic skills and dispositions necessary for enterprise management and supervision of other people, e.g. activity planning, openness to suggestions, delegation skills.2. Meeting challenges (4 statements) – the skills to derive satisfaction from undertaking new tasks, resolving problems and the use of stress as a motivational factor.3. Flexibility (4 statements) – the ability to take a break from professional matters through other interests, and not needlessly worry about the activities of rival entrepreneurs. 4. Perseverance (7 statements) – the ability to put effort into fulfilling tasks and to keeping promises or agreements shared with a conviction that effort brings results.5. Openness (5 statements) – refers to a variety of tasks undertaken and to consideration of other points of view, acquaintances and the skills to communicate with them.6. Independence (4 statements) – the skill to uphold opinion against the resistance of others, to take calculated risks and accept constructive disagreement for the benefit of the status quo.7. Understanding of socio-economical factors (8 statements) – the knowledge of social and economical factors influencing economic activity e.g. workplace discrimination, healthcare and social benefits system rules.8. Understanding of the functional factors (5 statements) – the awareness of the existence of competition and the necessity to create an image for the enterprise; the skill to obtain legal advice referring to issues important for the enterprise e.g. accountancy, insurance. 9. Advertising competencies (4 statements) – the skills connected with promotion and advertisement of the enterprise.10. Competencies to compete (6 statements) – market skills derived from the knowledge of market rules and competition recognition.11. Financial knowledge (8 statements) – the skills of financial management. On the formal side it is connected with budget planning and knowledge of economic rules, on the practical side it refers to the ability to calculate breakeven point, the ability to read financial statements and calculate production costs.

|

5. Determining the Required Competence Levels

- In order to determine the required competence levels, which is sufficient for micro firm success, research on successful entrepreneurs was conducted. The successful micro firm’s managers participating in the study fulfilled all the following criteria: 1) they had established the company themselves (i.e. did not takeover an existing company) 2) they had run the company for at least three years 3) they did not plan to stop running the company within the next three years 4) they are satisfied with their activity (in answer to the question "How satisfied are you with your company?" on a scale from 0 to 100, with the minimum assumed as 50 points). Each of the managers taking part in this study filled up the Astra-Manager method.

5.1. The Participants

- The group of managers studied comprised of 40 entrepreneurs, the majority men (65%). Half of the group lived in small towns (50%), the rest in big towns (25%) and villages (25%). Their age ranged between 28 and 56 years (M = 42.98) and they had approximately 15 years of education (M = 15.11). The companies set up by these managers had been in business between 3 and 24 years, in average more than 9 (M = 9.20). Most of the companies were private (57.9%) and run by individuals (23.7%). The minority of companies had legal identity (5.3%) and the rest belonged to the public sector (13.2%). All the managers had established their companies themselves and did not plan to close it for the following three years. These managers presented a moderate level of satisfaction from their companies achievements (M = 68.5).

5.2. Results

- The results obtained by successful micro firm’s managers can constitute the point of reference for assessment made using the Astra-Manager scales (tab. 2).

6. The Ways to Use Astra-Manager

- The Astra-Manager method can be used in either a paper or electronic version. In the paper version the answers are given on the 100-grade scale. In the electronic version, a so-called slider is used, that can be moved using a mouse.After the evaluation is completed the managers receives an individual competencies profile and a comparison with successful managers profile obtained on the basis of described above research. The discrepancy between both profiles allows an estimate of the need for development in the area of specific competencies, and recognition of possible training needs. The person being evaluated also receives suggestions for available ways to develop competencies, where the results were lower than in the group of successful managers.However, using the method we have to be aware that it is a self-assessment tool. Because of this it may be vulnerable to the influence of social approval. Some people may tend to present themselves in a more positive manner and evaluate their competencies as higher than they in fact are. The possibility of such subjective evaluation (increasing results) should be considered when those results are used to design a specific training program.

7. Conclusions

- The Astra-Manager method allows the evaluation of the level of competencies both in the area of general competencies, such as perseverance and openness, and competencies referring directly to the management of a small company e.g. financial management. At present stage the method can be used for comparative studies of groups, e.g. of micro enterprises managers, leading their economic activity in different sectors and interested in participating in training. Since six language versions were developed, this method can be used in different countries. Because of the moderate reliability of some scales, this method should not be used for individual assessment, especially as a selection tool. It can though – comparing results of different people - indicate greater or lesser training needs in the area of analysed competencies. It can be helpful during the design of training programmes for small enterprise managers and adjustment of training content to the real needs of participants. If we can assess an individual’s strengths and weaknesses we can suggest areas where further development or counselling is needed[16]. The Astra-Manager tool has to be qualified as self-description method and it generates some limitations comparing to the direct observation methods like e.g. assessment/development centre. Even with the acceptable prognostic value this tool does not measure actual behaviours; the result is based only on the declarative answers. The answers may be vulnerable to the influence of social approval.This method will eventually allow measurement of twelve competencies which were distinguished according to the results of the Factor Analysis. However, it does not exhaustively list the qualities required for entrepreneurial operations. The group described as entrepreneurs is internally very diverse. The scope of their activities can also be diverse – from a small one person, or family owned company to bigger enterprises. The diversity refers also to branch or economic sectors. It is also presumed that cultural differences appear – in different countries different competence sets can bring success in economic activity operations[11, 21]. This subject requires further research. Further works on the method could aim to establish the required level of competencies for managers acting in those different areas, branches or countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank all the members of Leonardo da Vinci ASTRA project, for their help during the tool preparation.

References

| [1] | Lans Thomas, Biemans Harm, Mulder Martin, Verstegen Jos, “Self-awareness of mastery and improvability of entrepreneurial competence in small business in the agrifood sector”, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Human Resource Development Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 147-168, 2010. |

| [2] | Shane Scott, Venkataraman Sankaran, “The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research”, Academy of Management, Academy of Management Review, vol. 25, no.1, pp. 217-226, 2000. |

| [3] | McClelland David, “Testing for competence rather than for “intelligence”’, American Psychological Association, American Psychologist, vol. 28, no.1, pp. 1-14, 1973. |

| [4] | Raven John, Competence in modern society: its identification, development and release, Oxford Psychologists Press, UK, 1984. |

| [5] | Armstrong Michael, A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, Kogan Page, UK, 2006. |

| [6] | Rankin Neil (ed.), The IRS Handbook on competencies: law and practice, IRS, UK, 2001. |

| [7] | Adams Katherine, “Interview with David McClelland”, Competency, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 18-23, 1997. |

| [8] | Boyatzis Richard, The competent manager: a model for effective performance, John Wiley & Sons, USA, 1982. |

| [9] | Van Beirendonck Lou, Competentiemanagement: The essence is human competence, Acco, Belgium, 2001. |

| [10] | Shane Scott, Locke Edwin, Collins, Christopher, “Entrepreneurial motivation”, Elsevier Science, Human Resource Management Review, vol. 13, pp. 257-279, 2003. |

| [11] | Shook Christopher, Priem Richard, McGee Jeffery, “Venture creation and the enterprising individual: a review and synthesis”, Sage Publications, Journal of Management, vol. 29, pp. 379-399, 2003. |

| [12] | Laguna Mariola, “Positive psychology inspirations for entrepreneurship research”, In: Lukes Martin, Laguna Mariola (eds.) Entrepreneurship: A psychological approach (pp. 73-88). Oeconomica, Czech Republic, 2010. |

| [13] | Laguna Mariola, “Self-efficacy, self-esteem, and entrepreneurship amongst the unemployed”, Educational Publishing Foundation, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, in press. |

| [14] | Markman Gideon, Baron Robert, “Person-entrepreneurship fit: why some people are more successful as entrepreneurs than others”, Elsevier Science Inc., Human Resource Management Review, vol.13, pp. 281-301, 2003. |

| [15] | Obschonka Martin, Silbereisen Rainer, Schmitt-Rodermund Eva, “Successful entrepreneurship as developmental outcome: A path model from a lifespan perspective of human development”, Hogrefe Publishing, European Psychologist, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 174-186, 2011. |

| [16] | Vecchio Robert, “Entrepreneurship and leadership: common trends and common threds”, Elsevier Science, Human Resource Management Review, vol. 13, pp. 303-327, 2003. |

| [17] | Douglas Susan, Craig Samuel, “Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation”, American Marketing Association, Journal of International Marketing, vol.15, no.1, pp. 30-43, 2007. |

| [18] | Kim Jae-On, Mueller Charles, Introduction to factor analysis. What it is and how to do it, Sage Publications, USA, UK, 1986a. |

| [19] | Kim Jae-On, Mueller Charles, Factor Analysis. Statistical methods and practical issues, Sage Publications, USA, UK, 1986b. |

| [20] | Brzeziński Jerzy, Metodologia badań psychologicznych (Methodology of psychological research), PWN, Poland, 2005. |

| [21] | Moriano Juan Antonio, Gorgievski Marjan, Laguna Mariola, Stephan Ute, Zarafshani Kiumars, “A cross cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention”, Sage Publications, Journal of Career Development, vol. 39, pp. 162-185, 2012. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML