-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2020; 10(1): 9-19

doi:10.5923/j.health.20201001.02

Received: Nov. 8, 2020; Accepted: Nov. 23, 2020; Published: Nov. 28, 2020

Perceived Determinants of Domestic Violence and the Strategies for Its Prevention in Orlu Local Government Area of Imo State, South East Nigeria

Cynthia Oluchi Okorie1, Philip Etabee Bassey1, Nuria S. Nwachuku1, Antor O. Ndep1, 2

1Public Health Department, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria

2Enareh Public Health Consultancy, B4/19 MSQ, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Philip Etabee Bassey, Public Health Department, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Heading: Perceived determinants of domestic violence and the strategies for its prevention in Orlu Local Government Area of Imo State, South East Nigeria. Background: Domestic violence (DV) also referred to as intimate partner violence (IPV) is considered a norm, tolerated, and often veiled in a culture of silence in Nigeria. Understanding of the contextual socio-cultural factors fueling this practice in patriarchal societies may help set the tone for addressing it. Objectives: This study aimed at determining adults’ perceptions on intimate partner violence and a trend analysis of reported cases between 2013-2016 in Orlu. Methods: A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study involving a total of 440 subjects (220 men and women) was conducted. The study also included review of documented incidents of DV/IPV reported to the police between 2013 and 2016 in the study area. Results: All 440(100%) respondents agreed that disobeying or ‘talking back’ to the male partner were major causes of domestic violence. Unemployment, 435(98.9%), refusing to have sex, 419(95.2%) and delay in serving meals, 380(96.4%), alcohol influence, 310(62.5%), suspicion of infidelity, 300(68.2%), and disagreement over finances, 275(62.5%) were also important contributory factors. Reviewed police records indicated steady increase in reported IPV incidents from 79(20.3%) in 2013 to 185(47.6%) in 2016. Effective communication between partners 440(100.0%) could help reduce the trend. More respondents, 271(61.6%) suggested that victims should quit the relationship, while 251(57.1%) opined that reporting incidents of DV/IPV to the police could act as a deterrent. Conclusions: Female partners were usually the victims of DV/IPV. Police records show increasing trends in DV/IPV however, none of the offenders were prosecuted. Criminalizing DV/IPV offences and ensuring victims obtain justice could help reduce this upward trend.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Intimate partner violence, Socio-cultural factors

Cite this paper: Cynthia Oluchi Okorie, Philip Etabee Bassey, Nuria S. Nwachuku, Antor O. Ndep, Perceived Determinants of Domestic Violence and the Strategies for Its Prevention in Orlu Local Government Area of Imo State, South East Nigeria, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 9-19. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20201001.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Domestic violence, also known as domestic abuse, spousal abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV), battering, and family violence, is a pattern of abusive behaviors by one partner against another in an intimate relationship such as marriage, family, dating or cohabitation [1]. Actions that are manifestations of domestic violence (DV) include: physical aggression or assault (shoving, hitting, slapping, kicking, biting, restraining, throwing objects), threats, criminal coercion, emotional/psychological abuse; intimidation, stalking, controlling or domineering; endangerment, unlawful imprisonment, kidnapping, trespassing, denial of access of the victim to family or friends, harassment, humiliation, as well as passive abuse otherwise known as neglect or economic deprivation [2,3]. Sexual violence or abuse on the other hand entails being physically forced to have sexual intercourse against one’s will, or yielding to a sexual act out of fear of what one’s partner might do, or being compelled to engage in degrading and undignifying sexual acts [1-3]. Domestic violence can happen to a man or woman in all settings regardless of age, race, cultural group, religion or socioeconomic status. The overwhelming global burden of IPV is however borne by women [1,4]. The frequency and severity of domestic violence also vary among partners and across cultures and societies; however, the recurring decimal of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other by the use of force or by coercion. Each incident builds upon previous episodes, thus setting the stage for a cycle of violence [2,3]. Domestic violence is therefore not a new phenomenon; neither are its consequences to women’s physical, mental and social well-being. reproductive health. It spans history and cultures and affects people across society, irrespective of their religion and socioeconomic status [1,4] The unmistakable narrative is the growing awareness of the fact that acts of violence against women are not isolated events but rather form a pattern of behavior that have been accepted in some societies as acceptable societal or cultural norms even though these practices violate the rights of women and girls, damage their health and well-being and also limit their participation in society [5,6]. The prevalence of IPV, has been estimated from population-based surveys; notable among them is the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women which involved the collection and analysis of IPV data from more than 24 000 women in 10 countries, representing diverse cultural, geographical and urban/ rural settings [7]. The study confirmed that IPV is prevalent in all the countries studied. The proportion of women in intimate relationship who reported ever having experienced physical violence by a partner ranged from 13–61%; about 4–49% of the women reported having experienced severe physical violence, 6–59% reported sexual violence by a partner at some point in their lives; while 20–75% had been emotionally abused by a partner in their lifetime [7]. A comparative analysis of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from nine countries also found that for physical violence, the percentage of women in intimate partnership who reported ever experiencing any physical or sexual violence by their current or most recent husband or cohabiting partner, ranged from 18% in Cambodia to 48% in Zambia, and 4% to 17% for sexual violence [8]. An analysis of the DHS data for physical or sexual IPV ever reported by currently married women for 10 countries ranged from 17% in the Dominican Republic to 75% in Bangladesh [6]. The findings from a systematic review of studies on the global prevalence of violence against women indicated that approximately one third of women globally are affected by this global public health malady. [1] In this regard, the United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women defined gender based violence (GBV) as: “Any act of violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life [5]. A Crime Survey report for England and Wales (CSEW) of adults aged 16 to 59 who experienced any type of domestic abuse (emotional, physical and financial) by partners or family members, as well as sexual assaults and stalking by a current or former partner or other family member in the year ending March 2015, estimated that 8.2% of women and 4.0% of men reported experienced any type of domestic abuse; equivalent to an estimated 1.3 million female and 600,000 male victims respectively [9]. The prevalence and determinants of domestic violence of different societies and cultures have been extensively studied in several countries across the globe [6-8,10-12] including Nigeria [13-15]; however, there is a paucity of studies on the perceptions of individuals and communities about IPV and how it can be eliminated or prevented in Nigeria. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge no previous study on domestic violence in Nigeria had included the examination of the cases of IPV reported to the police. This study was therefore conceived to assess the trend in the number of cases of IPV reported to the police department in Orlu local government area (LGA) of Imo State in the South Eastern part of Nigeria as well as explore the factors influencing IPV as perceived by male and female members of the locality and how best it can be prevented or eliminated.

2. General Objective

- The general objective of this study was to determine the factors influencing domestic violence in Orlu LGA of Imo state, Nigeria.

2.1. The Specific Objectives of This Study were to

- ο Determine the general perceptions of men and women about domestic violence.ο Assess the socio-cultural perceptions of the respondents about DV.ο Identify the perceived causes of domestic violence among intimate partners in Orlu LGA of, Imo state.ο Determine the prevalence of domestic violence in Orlu L.G.A using records obtained from courts, police stations, and NGOs involved with IPV.ο Identify the preventive measures against domestic violence in Orlu L.G.A.

2.2. Research Questions Formulated for the Study

- ο What are the general perceptions of men and women on domestic violence?ο What are the socio-cultural perceptions of the respondents about domestic violence?ο What are the perceived causes of domestic violence among partners in Orlu L.G.A.?ο What is the prevalence of domestic violence in Orlu L.G.A, Imo State?ο What are the preventive measures against domestic violence in Orlu L.G.A?

3. Method

- A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study involving a total of 440 subjects (220 men and women) was carried out in Orlu LGA of Imo State in South Eastern Nigeria to identify the determinant factors of gender based violence. A retrospective review of incidents of gender-based violence between 2013 and 2016 reported to the police was equally carried out.

3.1. Study Population

- The population for this study included men and women aged 15 – 60 years who are permanent residents of Orlu LGA.

3.2. Sample Size Determination

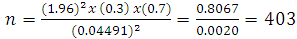

- The sample size was determined using the Bluman’s formula, (Bluman, 2004) which is given as { n = Z2pq / d2} [16].Where n = the desired sample size; P= estimated prevalence of domestic violence (30%) obtained from the WHO 2013 Global and regional estimates of violence against women (1); q=1-P (Proportion of non-occurrence of DV); z = the standard normal deviate set at 1.96 which corresponds to 95% confidence level; d = the precision or margin of error was set at 0.04. Inputting the figures into the equation gives the following result:

The sample size for this survey was approximately 403, however, 10% of 403 (approximately 40) was added to make up for non-response or attrition bias, bringing to the total sample required to 440 subjects.

The sample size for this survey was approximately 403, however, 10% of 403 (approximately 40) was added to make up for non-response or attrition bias, bringing to the total sample required to 440 subjects. 3.3. Sampling Procedure

- A multistage sampling technique was used to select 440 respondents for this study. Since there are thirteen political wards in Orlu LGA, a simple random sampling method was applied in selecting five wards. By applying a simple random sampling method, two communities each were then selected from the five selected political wards, yielding a total of ten communities. Forty-four houses were then selected from each of the selected communities through systematic sampling technique based on a determined selection interval. A simple random selection method was then applied in selecting forty-four households from the selected houses; depending on the available number of households living in each house. Finally, a purposive sampling technique was applied to select 220 equal numbers of eligible male and female respondents aged 15 – 60 years) from the households.

3.4. Data Collection Instrument(s) and Data Collection

- Primary and secondary data was generated for this study. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to generate the primary data while the secondary data was generated by reviewing records from courts, police stations, and the welfare department. The questionnaire was divided into four (4) sections (A – D) as follows: Section A – Socio-demographic data, Section B – Perceptions on DV, Section C – Knowledge of the causes of DV and Section D – Preventive measures. The questionnaire was interviewer-administered.The questionnaire was pre-tested to ascertain its content validity and reliability among 22 residents (i.e. 5% of the study sample) in the Mbukpa community in Calabar South LGA of Cross River State. The feedback obtained was applied to improve the consistency of the instrument.

3.5. Data Analysis

- Data generated from the completed questionnaire was analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 16. Frequency distributions were run on the data and results were presented as frequencies /percentages in tables, figures and charts.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

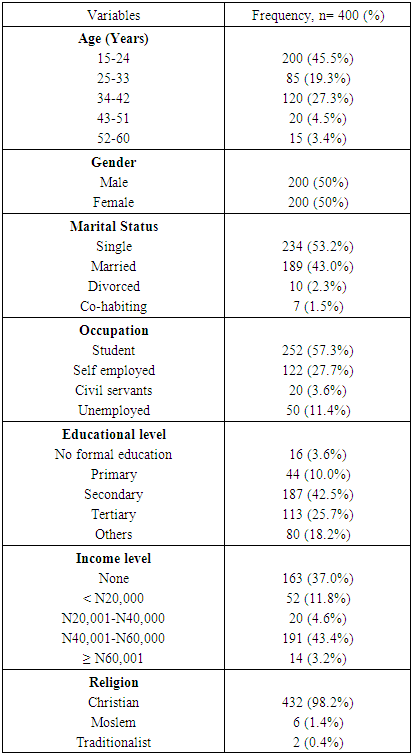

- The results on socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents as shown in Table 1 indicates that majority 200(45.5%) of the respondents were between the ages of 15-24 years. The second highest age category with 120 respondents were those age 25-33years. While the least number 15(3.4%) were in the age category 52-60. Majority of the respondents 234 (53.2%) were single, 189(43.0%) were married, 10(2.3%) were divorced, 7(1.5%) were co-habiting. By occupation, 252 (57.3%) respondents were students, 122(27.7%) were self-employed, 50(11.40%) were unemployed, while 20(3.6%) were civil servants. 16(3.6%) of the subjects had no formal education, 44(10.0%) had primary level education, 187(42.5%) had secondary level of education, 113(25.7%) had attained tertiary level of education while 80(18.2%) had other forms of education. On income level, 52(11.8%) of the respondents earned incomes of less than 20,000 naira (equivalent of $50) per month, 20(4.6%) of the respondents earned incomes of 20,001-40,999 naira ($50.003-$102.5) monthly, 191(43.4%) had incomes of 41,001-60,999 naira ($102.51- $152.5) per month, while 14(3.2%) earned 61,000 naira ($152.52) and above as income. (see Table 1)

|

4.2. General Perceptions of Men and Women About Domestic Violence

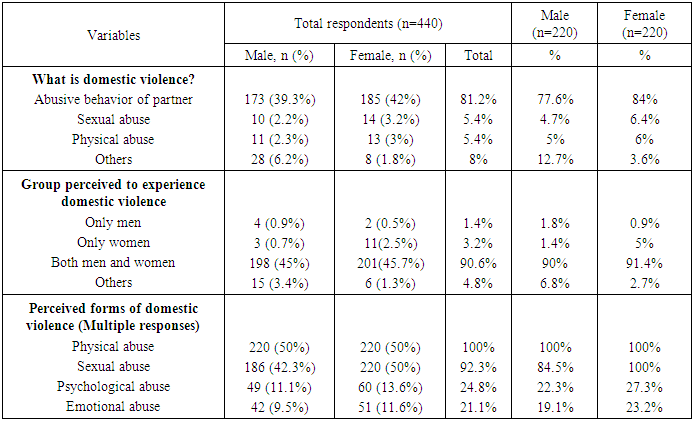

- The result of the general perceptions of the respondents about domestic violence is shown in Table 2. Overall 173(39.3%) of the male respondents knew domestic violence as an abusive behavior of a partner compared with 185(42.0%) of the female respondents. When considered on a gender basis, more women 84% compared with men 77.6% perceived DV as an abusive behavior of a partner. Both genders 201(91.4%) females and 198(90%) males agreed that men and women can be victims of DV. On the perceived forms of DV experienced in an intimate relationship, both men and females were unanimous (100%) agreed that DV involves physical violence. All the 220 women agreed that DV included sexual violence, however, only 186(84.5%) of the men agreed that DV included sexual violence. More women 60(27.2%) and 51(23.2%) compared with 49(11.1%) and 42 (9.5%) respectively were of the opinion that psychological and emotional abuse were other forms of DV.

|

4.3. Socio-Cultural Perceptions of the Respondents about Domestic Violence

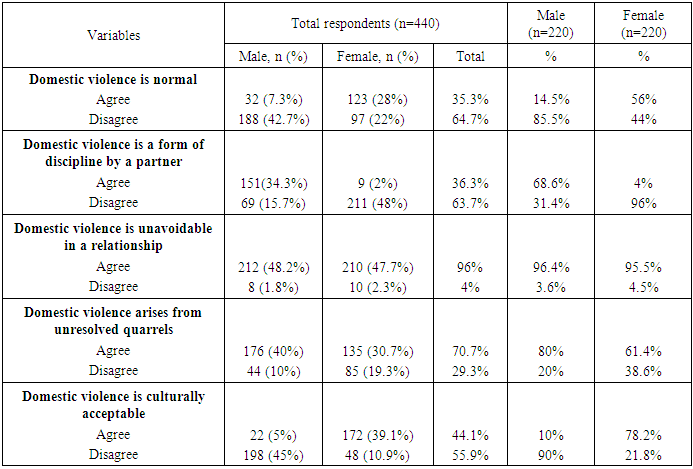

- On the socio-cultural perceptions of the respondents about DV as shown in Table 3, majority of women, 123(56%) compared with 32(14.5%) men agreed that DV is a normal social behavior, while 188(85.5%) males and 97(22%) women disagreed that DV is an accepted social norm. Majority of men 151(68.6%) compared 9(4%) women agreed that DV is a form of discipline by a partner. 211(96%) of women disagreed as opposed to 69(31.4%) of the male respondents. With regards to whether DV was unavoidable in a relationship, 212(96.4%) males and 210(95.5%) females were affirmative while 8(3.6%) males and 10(4.5%) females respectively disagreed. 176 (80%) males and 135(61.4%) women agreed that DV arises from unresolved quarrels. With regards to the cultural acceptability of DV, 172(78.2%) of women and 48(21.8%) of males agreed that DV was culturally acceptable.

|

4.4. Perceived Causes of Domestic Violence

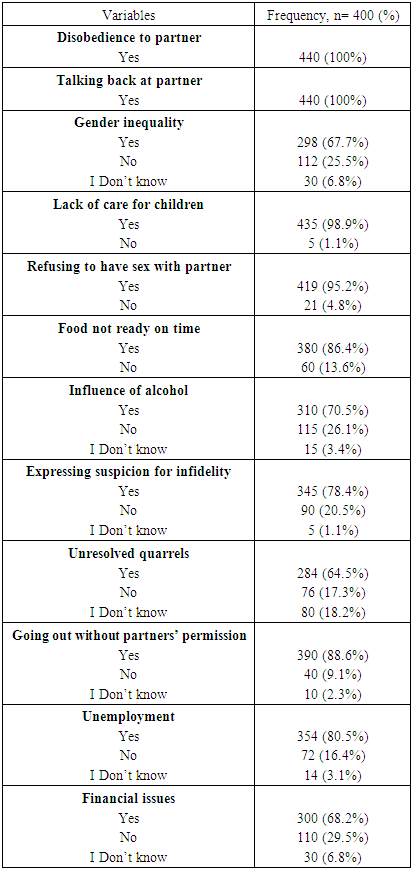

- The respondents’ answers to the questions regarding their perception of the causes of DV as shown in Table 4 indicates that all the respondents 440(100.0%) were in agreement that disobedience to partner as well as talking back at ones’ partner can engender DV. 419(95.2%) indicated that refusing to have sex with partner can incite DV. 380(86.4%) subjects stated that not serving meals on time could cause DV. The role of alcohol in causing DV was mentioned by 310(70.5%) respondents, while 345(78.4%) subjects cited the suspicion of infidelity of a partner as a causal factor.

|

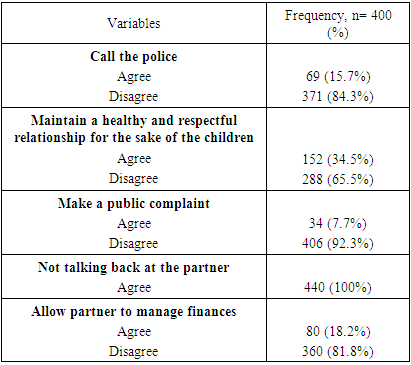

4.5. Respondents’ Suggestions of Ways Victims of Domestic Violence Can Prevent Further Abuse

- With regards to how victims of domestic violence can respond to the abuse, all the 440 respondents indicated the victim should not talk back at the abusive partner to avoid provocation. 371(84.3%) of the respondents disagreed with the option of calling the police when a partner becomes abusive. 406(92.3%) subjects also disagreed with the notion of going public about the abusive behavior. On the option of remaining in an abusive relationship for the sake of the children, 152(34.5%) agreed while 288(65.5%) disagreed. The option of allowing a partner to manage the finances as a way of ensuring peace was favored by 80(18.2%) while 360(81.8%) disagreed with the option. (see Table 5)

|

4.6. Result of the Analysis of the Data Obtained from the Police Records

- The findings of the data extracted from the police records showed that the cases of domestic violence reported to the police were not properly documented: for instance, there were no separate records for men and women. The entries made in the register included the following: the date of the incident, demographic details of victims and offenders, and the type of IPV committed. There was no column for the cause of the domestic violence, nor was there any documentation of the cases that were charged to court, referred to a correctional center or other follow-up actions.

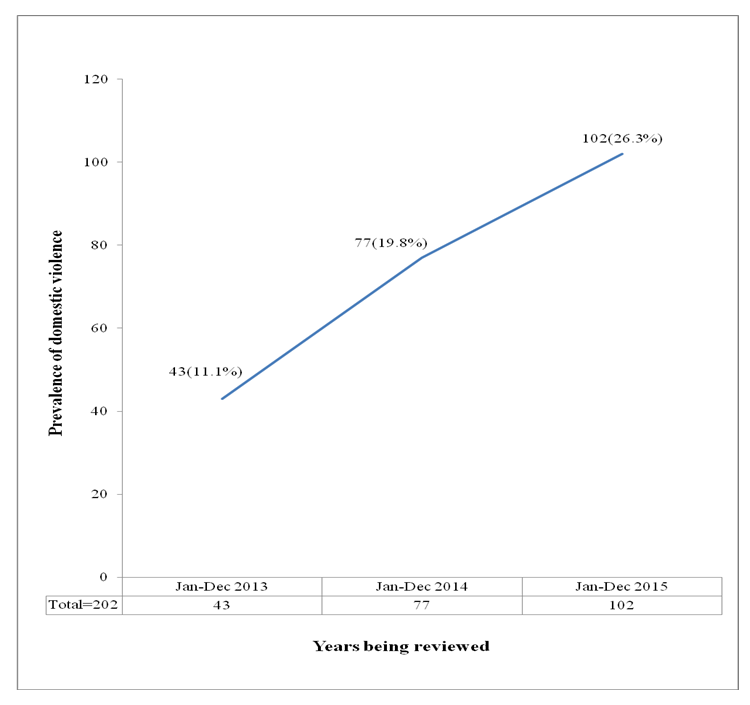

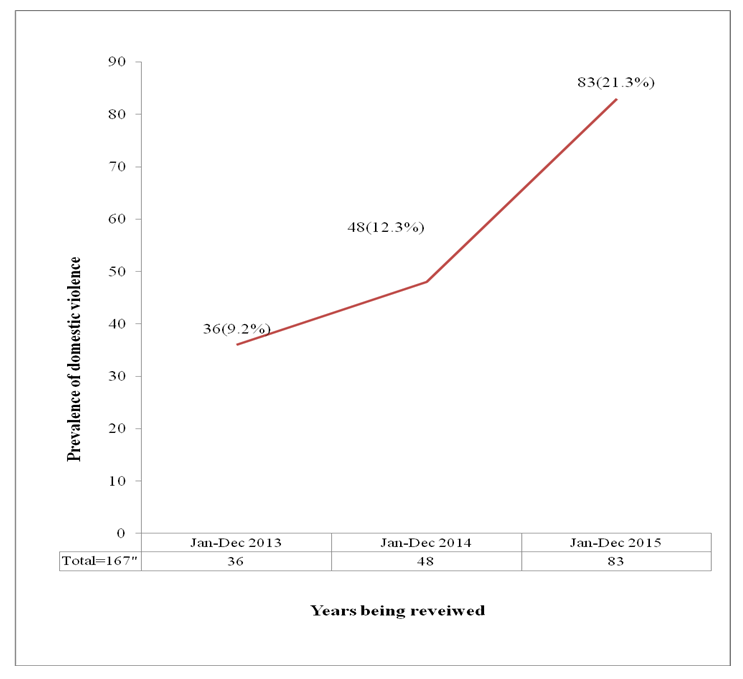

4.6.1. Prevalence of Domestic Violence among Men and Women from the Police Records

- The analysis of the data obtained from the police records showed that a total of 389 incidents of domestic violence involving 222(57%) females and 167(43%) males. were reported to the police within the period 2013 to 2015. The records indicated steady increase in reported IPV incidents from 79(20.3%) in 2013 to 185(47.6%) in 2016. In 2013, 43(11.1%) women were abused compared to 36(9.3%). In 2014, 77(19.8%) women and 48(12.3%) males respectively were abused. In 2015, 102(26.2%) females and 83(21.3%) respectively suffered one form of DV or the other. See details in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

| Figure 1. Prevalence of domestic violence among women in Orlu within the period of 2013 to 2015 using police records |

| Figure 2. Prevalence of domestic violence among men in Orlu within the period of 2013 to 2015 from police records |

5. Discussion

- Domestic violence has rightly been described as an inhuman practice [17,18], which violates the human rights and personal dignity of the victim [19-21], and above all damages the physical, mental and psychological well-being of the victim [22-23]. Tjaden et al [24], in their study on DV, found that physical violence was typically accompanied by psychological abuse resulting in the following psychological consequences: anxiety, depression, flash-backs, replaying assault in the mind and fear of intimacy.Studies have shown that abused women were twice as likely as non-abused women to report poor health and physical and mental problems, even if the violence occurred years before [7,25]. Women who are abused by their partners suffer higher levels of depression, phobias and anxiety than non-abused women [26]. This study sought to assess the general perception of our respondents (men and women) about domestic violence and the causal factors. The response obtained, showed that both male and respondents were in agreement that domestic violence involves physical, sexual and psychological abuse by a partner and that it can be perpetrated by both males and females.

5.1. Perceived Causes of Domestic Violence

- On the perceived causes of DV, both male and female respondents, agreed unanimously (100%) that disobedience to partner and talking back at one’s partner could provoke partner abuse. There was also some consensus between the males and females that the following factors: refusal to have sex with one’s partner 419 (95.2%), not preparing meals on time 380(86.4%), or not giving attention to the upkeep of children 435(98.9%), influence of alcohol 310(70.5%), expression of suspicion of infidelity by a partner 345(78.4%), unresolved quarrels 284(64.5%), unemployment 354(80.5%), financial issues 300(68.2%), gender equality 298(67.7%), and going out without spousal approval 390 (88.6%) could equally provoke domestic violence. Evidences from previous studies have highlighted various factors that could predispose individuals to domestic violence. The American Centre for Disease Control (CDC) identified the following as risk factors: Use of drugs or alcohol, witnessing violence or being a victim of violence as a child, unresolved quarrels, socio-cultural factors that support wife beating, competition/jealousy about spousal achievements, unemployment; which is more so when the male partner is the unemployed one [27]. Other risk factors include tradition and norms within African traditional culture that regard wife battering and harsh discipline as normal, economic stress, conflict or dissatisfaction in the relationship, male dominance in the family, man having multiple partners, as well as broad social acceptance of violence as a way to resolve conflict [28]. Obi et al. [29] found that domestic violence was significantly associated with financial disparity in favor of the female, influential in-laws, educated women and couple within the same age group. It should however be borne in mind that the presence of these causal factors does not necessarily imply that domestic violence will occur.

5.2. The Role of Socio-Cultural Beliefs and Norms

- Our study explored the role of culture and societal norms as causal factors of domestic violence. Our respondents were however divided along gender lines on their perception of the socio-cultural norms about domestic violence. 56% of the female respondents assented that DV was a social norm while 85.5% of the men disagreed. Most (68.6%) of the men respondents agreed that domestic violence is a form of discipline while majority (96%) of the female respondents disagreed with that assertion. With regards to the perception of domestic violence as a culturally accepted behavior most (78.2%) female respondents agreed while most (90%) of the male respondents disagreed. Tran et al. [11], studied the “Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence against Women among Women and Men in 39 Low and Middle-Income Countries in which they examined the attitude of women and men on the subject of justification for wife beating using data from Round Four of the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS).They assessed attitudes about IPV against women using a single set of fixed response yes/no questions that reflected widely accepted gender stereotypes about women’s roles and responsibilities: one of the questions for instance is as follow: “Is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in any of the following circumstances” (a) she goes out without telling him, (b) she neglects the children, (c) she argues with him, (d) she refuses to have sex with him, (e) she burns the food. Attitudes that were in consonance with the acceptance of IPV were scored as 1 if the respondents indicated with a “Yes” answer at least one of the five listed situations, and was scored as 0 if none of the options was endorsed [11]. The result of the study showed that the proportions of women who held attitudes that ‘wife-beating’ was justified in any of the five circumstances varied widely among countries from 2.0% (95% CI 1.7;2.3) in Argentina to 90.2% (95% CI 88.9;91.5) in Afghanistan. Similarly, among men it varied from 5.0% (95% CI 4.0;6.0) in Belarus to 74.5% (95% CI 72.5;76.4) in the Central African Republic [11].Moreover, the belief that ‘wife-beating’ is acceptable was most common among respondents in Africa and South Asia, and least common among respondents in Central and Eastern Europe, the Caribbean and Latin America. This belief was generally more common among people in disadvantaged circumstances such as being a member of a family in the lowest household wealth quintile, living in a rural area and having limited formal education [12].The results of a cross-sectional study of the 2013 Nigerian Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) involving 20,802 ever-partnered women aged 15–49 years, by Benebo et al [30], using multilevel logistic regression modeling to assess the association of individual- and community-level factors with IPV, showed that about one in four women in Nigeria reported having ever experienced intimate partner violence. After adjusting for covariates in the analysis, the result showed that higher status of women was protective (OR=0.47; 95% CI=0.32–0.71). However, the odds were reversed (OR=1.89; 95% CI=1.26–2.83), when community norms among men that justified IPV against women was added to the mode. The authors therefore concluded that besides women’s status, community norms towards IPV are an important predictor for the occurrence of IPV. Thus, a community-wide approaches aimed at changing norms among men is a sine qua non for preventing or elimination IPV especially in patriarchal male dominated societies such as Nigeria [30]. Evidences from the various studies on IPV have shown that socio-culturally defined gender stereotypes and attitudes that have made IPV acceptable and culturally normative are among the most significant factors that have been associated with the likelihood of perpetration of IPV and the lukewarm social responses to its perpetration [31-34]. Consequently, women who believe that IPV is acceptable and normative are more likely to blame themselves for the violence, and are less likely to report the problem to civil authorities or other family members Thereby enduring the humiliation, suffering and pains in silence and the long-term sequel of mental health problems [35].

5.3. Prevention of DV

- Domestic violence can lead to several negative sexual and reproductive health consequences for women, such as sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, unintended and unwanted pregnancy, pregnancy complications, abortion, pelvic inflammatory disease, urinary tract infections and sexual dysfunction, therefore its prevention is important to safeguarding the physical and psychosocial well-being of would-be victims [36-37].In this regard, our study also sought to determine the perceptions of how victims of DV can prevent the partner abuse. On the option of reporting the perpetrator to the police, only 69 (15%) respondents agreed that the matter should be reported to the law enforcement agency; the other 371(84.3%) respondents were opposed to reporting the matter to the police. This negative position was also upheld on the question of whether the abusive behaviors should be publicized or not. 34(7.7%) respondents agreed, while 406(92.3%) disagreed.The overwhelming opposition to the notion of involving the police in DV matters or exposing the perpetrator is quite predictable in Nigeria. This is largely because most cultures and societies in Nigeria and indeed Africa at large believe that domestic violence is a private affair that should be handled by the persons involved or where necessary their family members.All the 440 respondents were however unanimous on one option for preventing partner abuse, which is “not talking back at an abusive partner”. Majority of the respondent were however opposed to the idea that a victim of abuse should remain in the abusive relationship for the sake of the children. 288(65.5%) of the respondent disagreed with the notion that an abused spouse should endure the abusive relationship in the interest of the children. In a similar response, 360(81.8%) of the respondents opposed the idea of allowing an abusive partner take charge of the victims finances as a guarantee for peace.

5.4. The Involvement of the Police in Domestic Violence Matters

- The review of the records of cases of domestic violence reported to the police within the period in review showed that over the three-year period, more women 222(57%) than men 167(43%) were abused. There was also a progressive yearly increase of incidents of domestic that were perpetrated against both females and males. The availability of the police records provides some evidence that at least victims chose to report the incidents to the law enforcement agency. However, the figures may be an under-estimation of the actual prevalence of DV, since not all cases may have been reported. From the records the cases were not charged to court. This may not be unconnected with the notion that issues of domestic violence are considered as private issues that should be handled at best by the families of the victims and perpetrators. Kilpatrick et al (1992) noted that universally, relationship violence is to a large extent grossly underestimated because the documentation of reported incidents of DV depend on several factors, including the form of abuse and the decision of the victim or of an interested party to inform law enforcement [38]. This significant under-reporting is likely to be similar or greater for male victims of intimate partner violence. Consequently, it is only the reported cases of intimate partner violence that the law enforcement agencies have records about, but not about hidden unreported incidents. The under-reporting of intimate violence offences to the police is not uncommon because victims are often protective of their abusive partner [39]. The CSEW survey in the UK [9] found that women were more than twice as likely as men to tell the police (26% and 10% respectively) about domestic abuse. The most common reasons adduced by those that did not report the abuse, were that: the abuse was too trivial or not worth reporting (43%), it was a private, family matter and not the business of the police (37%), while (25%) of the victims reported that they did not think the police could help.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The findings of this study has shown that socio-cultural beliefs, norms and gender stereotypes play pivotal roles in the perpetration of domestic violence and that the attainment of the United Nations Sustainable Development goal 5 which is to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” may be a far cry if the inherent socio-culturally determined beliefs, norms and practices that have been entrenched to demean, suppress and brutalize the female gender are holistically addressed and discarded. It is obvious from available evidences that in spite of the educational, technological, scientific and social advancement of the 21st century, religion, culture and tradition still define and shape gender norms in most African societies. The norms and practices of male-dominated patriarchal societies that is deliberately skewed in favour of the male, and is the basis for justifying the continued perpetration of domestic violence especially against the female gender, have to a large extent sustained the existent primordial gender power imbalance.Efforts at changing these norms have often been resisted by vested male-interests. This is so because males dominate the socio-political and economic activities in most developing countries and even when legislations on gender equity are passed they are hardly defended or implemented. Moreover, even though in principle, UN charters about gender equity and human rights are the benchmarks and the required guiding principles for ensuring gender equity, the regulations are largely unenforceable or justiciable because of the apparent inertia of member nations particularly Low and middle income countries in Africa and Asia in adopting, and adapting them in line with global best practices by passing them through the required legislative processes to make that statutorily enforceable laws. In conclusion, religion and cultural beliefs fuel domestic violence in Nigeria, therefore beyond the domestication of the various UN conventions on Women rights and Gender Equity, the much needed high level governmental political will buttressed by cogent administrative policies and supportive legal frameworks that would ensure that violations are adequately punished should be entrenched in Nigeria. There is equally a need for socio-cultural reorientation for our men-dominated societies to appreciate the fact that wife battering is barbaric, primitive and inhuman; that there are dignifying and amicable sways of resolving domestic problems or conflicts other than wife beating. Domestic violence can also be prevented by addressing social and culturally entrenched gender stereotypes and potential risk factors that create friction and misunderstanding in an intimate relationship. Partners with alcohol or drug addiction problems should seek help for their addiction. Temporarily unemployed male partners should appreciate the efforts of their partners and make efforts to secure new jobs so as to deflate tensions arising from financial insufficiency and obligations that need to be met. Finally, no public health response to domestic violence can be meaningfully implemented without the institutionalization of primary prevention. This implies the complete abolition or stoppage of domestic violence through appropriate preventive and protective legislation, acculturation on gender equality and sustained behavior change communication to reinforce the desired new norm of mutual respect and love in intimate relationships. Future direction of this research will involve an assessment of the community’s knowledge of current state and federal legislation on domestic violence. Findings will inform a state-wide social marketing campaign aimed at educating the general public on the issue and its legal implications.

Disclosure

- The study was not supported or sponsored by any funding agency and there are no disclosures to be made.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML