-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2017; 7(5): 91-95

doi:10.5923/j.health.20170705.01

Knowledge of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation among Student Teachers in Nigeria

Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso1, Onyedikachi Oluferanmi Onyeaso2

1Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Department of Community and Social Medicine, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

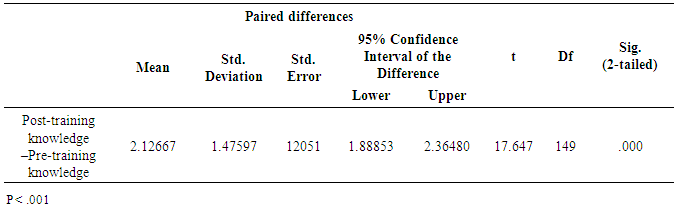

Background /Aim of Study: Although the teaching of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to of school teachers is highly recommended and practised in many countries across the globe for the purposes of generally increasing potential bystander CPR providers for out-of –hospital cardiac arrests in the community, informed management of emergency situations in schools as well as teaching of the school children the same, the situation is different in Nigeria. This study aimed at assessing the pre-training and post-training CPR knowledge of a group of Nigerian student teachers. Materials and Methods: A cohort quasi-experimental study involving 150 student teachers - 56 (37.33%) male and 94 (62.67%) female, age range of 17-28 years and mean age of 21.11 ± 2.40 (SD) was carried out in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt in June, 2017. By asking the participants to answer some questions in a questionnaire, their CPR knowledge before and after CPR training was tested. Results: The pre-training CPR knowledge of the student teachers was poor, but there was statistically significant improvement after the training (P = .000). Conclusion: Nigerian student teachers are very useful target group in the strategy for effective CPR training in Nigerian schools to produce potential bystander CPR instructors in our communities.

Keywords: CPR knowledge, Student teachers, Nigerian University

Cite this paper: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Onyedikachi Oluferanmi Onyeaso, Knowledge of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation among Student Teachers in Nigeria, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 91-95. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20170705.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It was strongly recommended that instruction in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) be incorporated as a standard part of the school curriculum [1, 2]. Although many school systems in other parts of the world have complied with these international standards with several publications supporting this [3-17], the situation is different in Nigeria with only few recently reported works on cardiopulmonary resuscitation involving the Nigerian school system [18-24].Cardiopulmonary resuscitation is a combination of rescue breaths and chest compressions which are intended to re-establish cardiac function and blood circulation in an individual who has suffered cardiac or respiratory arrest [25]. Cardiac / respiratory arrest is a very common emergency in not just the adult group but also in the neonatal period [26]. The medical science opined that the first 4-8 minutes in sudden collapse is the most crucial period in which resuscitation intervention is most needed [2]. If properly carried out effectively by a trained bystander in an emergency situation of cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can keep the victim alive until a medical expert takes over the care. When trained in CPR, children and adolescents can recognize the need for care and administer CPR [26]. However, the shortage of CPR instructors has been one of the limiting factors to increasing the number of potentially available bystander CPR providers in many communities [27, 28]. Consequently, there has been increasing support globally for school teachers to be trained in CPR so as to help train the school children as well as serve as bystander CPR providers both in the school environment and in the larger society [29-34].There is still paucity of published data on cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and school teachers in Nigeria with only two recent reports [35, 36]. In an attempt to contribute relevant data on this important subject for a developing country like Nigeria, the current report aimed at assessing the CPR knowledge of student teachers at the University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, in the South-South part of Nigeria. It was hypothesized that: (1) the CPR knowledge of the potential teachers for the Nigerian primary and secondary schools would not have poor CPR knowledge before being exposed to CPR training; (2) the CPR knowledge of the same group of student teachers would not be significantly better than their pre-training CPR knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

- A cohort quasi-experimental study involving one hundred and fifty two (152) 200-level undergraduate physical and health education students (student teachers) in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria was carried out. Out of the one hundred and fifty two (152) student teachers who filled the pre-training questionnaire on CPR knowledge, one hundred and fifty (150) completed the same questionnaire after the CPR training. Therefore, the final study sample size was one hundred and fifty (150) student teachers.The study took place in June, 2017. This convenience sample of the student teachers in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education were admitted in 2015 and are studying to graduate with Bachelor of Education Degree (majoring in either Health Education or Human Kinetics). They are being trained primarily to become teachers in primary and secondary schools. These student teachers are from different parts of Nigeria.The following null hypotheses were generated and tested:Ho1: That the pre-training CPR knowledge of the student teachers would not be poor.Ho2: That their post-training CPR knowledge would not be significantly different from their pre-training CPR knowledge.The methodology described below adopted in this study has been reported earlier [37].Stage 1 (Pre-training)A questionnaire, containing a section for the demographic data of the participants and a section having the questions on CPR to assess their pre-training cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge, was used. Stage 2 (Training and Immediate Post-training)Teaching was carried out for 60 minutes using American Heart Association (AHA) CPR guideline which is available online. Immediately after training the participants on the CPR technique using the manikins for their hands-on session, each of them was asked to answer the same questions they were given before the training. The process of training them on hands-on and the re-assessment took another 4 hours.Determination of Poor ‘CPR Knowledge’ and ‘Good CPR Knowledge’For the seven (7) questions on CPR knowledge, those who scored four (4) questions and above correctly were considered ‘Good CPR knowledge’ while any score less than that was considered ‘Poor CPR knowledge’.Statistical AnalysisThe Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze the data. In addition to descriptive statistics, both one-sample and two-sample T-test statistics were employed in the analysis and testing of the null hypotheses with significance level set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

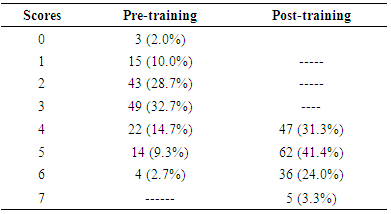

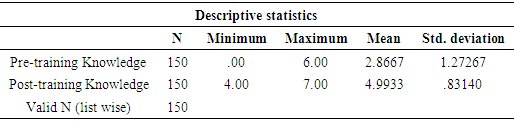

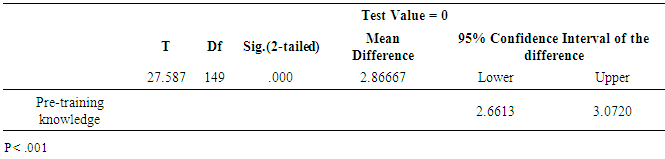

- The final cohort of one hundred and fifty (150) participants in this study was made up of 56 (37.33%) male and 94 (62.67%) female, age range of 17-28 years and mean age of 21.11 ± 2.40 (SD).Table 1 below shows 40 (26.67%, ‘Good CPR knowledge’) for the participants scoring four (4) questions and above rightly. The rest had 3 and below right. Meanwhile, all the participants scored 5 questions and above correctly during post-training assessment (100%, ‘Good CPR knowledge’).

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

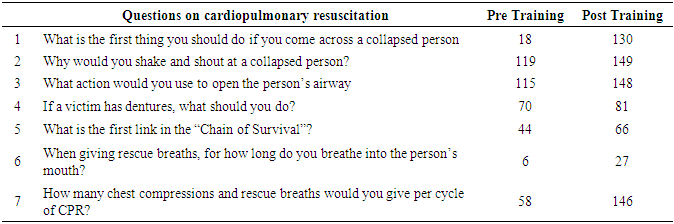

- The present Nigerian study has shown poor pre-training CPR knowledge by the Nigerian student teachers which significantly improved to good CPR knowledge during their post-training assessment. Although a similar earlier study among a group of Nigerian teachers [38] revealed the same pattern but the current study showed better pre-training CPR knowledge (26.67%) than that reported in the earlier study (2.4%). The better pre-training CPR knowledge observed among these student teachers could be due to some knowledge of CPR they gathered in their classroom lecture on first aid which was not centred on detailed teaching on CPR unlike those practising teachers who hardly had any teaching related to emergency care. Also, Patsaki et al [32] reported that as the age of the teachers increased, the ratio of the correct answers decreased. They equally reported that teachers were less motivated to be kept updated. The present Nigerian study has the age range of the student teachers as 17-28 years while the previous similar Nigerian study had older participants (practising teachers) with 20-50 years age range. Meanwhile, a Nigerian study among secondary school students that investigated the relationship between age, gender and school class and retention of CPR knowledge did not reveal any significant interaction between age and the their ability to retain CPR knowledge [24].Mpotos et al [33] reported poor CPR knowledge among the Flemish teachers despite the fact that majority of the (59%) had previous CPR training. In their report, 69% felt incompetent to perform correct CPR and 73% wished more training [33]. Similarly, the reports by Patsaki et al [32] had 21% of the Greek teachers with previous exposure to CPR training and many had mediocre level of knowledge of basic life support, automated external defibrillation, and foreign body airway obstruction. Al Enizi et al, [34] in their study involving mainly Saudi teachers, reported that despite the fact that 35.7% of their study population had previous CPR training, the average scores in their study did not show any difference between those who had previous CPR training and those who did not. The study concluded that secondary school teachers in Al-Qassim lacked CPR training and as such had little CPR knowledge or skills.In the pre-training phase, the present Nigerian study has 26.67% ‘Good CPR Knowledge’ which ended up in the post-training phase as 100% ‘Good CPR Knowledge.’ Considering the importance of introducing CPR teaching into the curriculum of Nigerian schools and its potential multiplying effect on increasing the number of potential laypersons bystander CPR providers in the community, this effort or advocacy should involve both students and teachers. A related Nigerian report [19] involving the school students gave only 8.9% pre-training CPR knowledge that later improved significantly to 88.6%. The impact of the CPR training on those students is comparable to the present report with pre-training 26.67% ‘Good CPR Knowledge’ which later became 100% ‘Good CPR Knowledge’ after the training. However, the participants in the present Nigerian study had better pre-training CPR knowledge than the secondary school students. This is understandable because the participants in the present study are undergraduate students who would have acquired some knowledge on emergency care as mentioned earlier compared to the very ignorant secondary school students.In the present Nigerian study it was observed that the least improvement in CPR knowledge from the pre-training to the post-training stages of the study was found in rescue breaths (6 to 27). This observation is consistent with related earlier reports where 2 to 6 (pre-training and post-training, respectively was reported [35] while the highest percentage of respondents (46.7%) indicated that they would not want to give mouth-to-mouth breathing to a stranger [38].

5. Limitation of the Study

- The present Nigerian study has the strength of having relatively adequate sample size and the participants (potential school teachers) were drawn from various States in Nigeria which makes it fairly representative. One of the University Admissions Policies in Nigeria, which the National Universities Commissions (NUC) oversees, is to admit students from every part of the country. However, this fairly representative nature of the study sample must be interpreted with caution because there is usually limited number of potential university students from the Northern parts of Nigeria that apply for admissions into the Nigerian Universities in the Southern parts of country.

6. Conclusions

- 1. Despite the poor pre-training CPR knowledge of the participants (student teachers) in this quasi-experimental study, their post-training CPR knowledge was significantly improved and better.2. Although their pre-training CPR knowledge is significantly poor, it is relatively better than those of similar earlier Nigerian studies [19, 35].

7. Recommendations

- Training student teachers in CPR is a major means of laying a strong foundation for Nigerian school children to be properly trained in CPR as well as increasing the number of potential bystander CPR providers in Nigerian community.More similar studies should be carried out in other Nigerian Universities in other parts of Nigeria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We remain very grateful to the renowned Professor of Orthodontics, Professor C O Onyeaso, for his guidance and encouragement during this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML