-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2017; 7(4): 84-90

doi:10.5923/j.health.20170704.03

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Skills of Some Undergraduate Human Kinetics and Health Education Students in a Nigerian University

Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso1, Onyedikachi Oluferanmi Onyeaso2

1Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Department of Community Medicine, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background /Aim of Study: There is a global support for the teaching of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in schools and teachers are expected to be trained accordingly so as to be effective trainers and to increase the number of potential lay person bystander CPR providers for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA). Meanwhile, Nigeria is yet to move in this direction. This study aimed at assessing the pre-training and post-training CPR skills of a group of Nigerian student teachers. Materials and Methods: A cohort quasi-experimental study design was carried out involving 150 student teachers in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt. Before the CPR training, the participants were exposed to a typical scene of a victim of cardiac arrest using a manikin and they were asked to demonstrate steps to resuscitate the victim. This was repeated after the CPR training sessions. Both the training and assessment of the participants were done by an American Heart Association (AHA) - certified CPR instructor. Using a modified AHA Evaluation Guide, the assessment was grouped into four CPR skills domains. Results: Although the pre-training CPR skills of the participants were significantly very poor, there was significant improvement after the training in all the CPR skills (P < .001). Conclusion: The Nigerian student teachers are promising potential CPR instructors for school children and the public, if encouraged as in the advanced parts of the world.

Keywords: Student teachers, CPR skills, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Onyedikachi Oluferanmi Onyeaso, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Skills of Some Undergraduate Human Kinetics and Health Education Students in a Nigerian University, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 84-90. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20170704.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation is a combination of rescue breaths and chest compressions which are intended to re-establish cardiac function and blood circulation in an individual who has suffered cardiac or respiratory arrest [1]. About 17.5 million people die each year from cardiovascular disease (CVD), an estimated 31% of all CVD deaths worldwide [2]. Furthermore, 75% of CVD deaths occur in low income and middle income countries while 80% of all CVD deaths are due to heart attacks and strokes [2]. According to ‘Global Heart’ Initiative launched on September 22, 2016, CVD including heart attacks and strokes is the world’s leading cause of deaths [2].Cardiac / respiratory arrest is a very common emergency in not just the adult group but can occur in children and even in the neonatal period [3-5]. The medical science opined that the first 4-8 minutes in sudden collapse is the most crucial period in which resuscitation intervention is most needed [5]. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be administered by a trained person before the arrival of Emergency Medical Services [1-5]. When trained in CPR, children and adolescents can recognize the need for care and administer CPR and it has been established to be successful in saving victims life when effectively performed [6-8]. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation is indeed an important life-saving first aid skills practiced throughout the world [4]. It is perhaps the only known effective method of keeping a victim of cardiac arrest alive long enough for definitive treatment to be delivered [4].Cuijpers et al [9] reported that training of secondary students on CPR by physical education student teachers was not inferior to the training by a registered nurse, suggesting that school teachers, student teachers can be recruited for CPR training in secondary schools.In another related study, school teachers were ambiguous about whether or not students are the right target group or which grade is suitable for defibrillator training, as well as about the deployment of defibrillators at schools [10].The authors opined that prior training and even little knowledge about defibrillators were crucial to their perception of student training [10]. Among other barriers to success of CPR in schools is paucity of teachers with CPR skills and the need for familiarization of teachers with CPR training kits [11]. In fact, teachers’ role in generally increasing the number of potential bystander CPR providers for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) victims is well established [12-20].Besides the training of the school children in CPR, saving of the life of a child who could be a victim of cardiac arrest would be very rewarding in addition to saving of an adult victim in the school environment.According to Zinckernagel et al [10], cardiac arrests in schools are rare events, but the death of a seemingly healthy young person can be especially devastating for the family and local community. In trying to encourage the incorporation of CPR teaching and training in Nigerian schools as in other parts of the world, some recent related earlier studies had been published [21-24].Therefore, this study aimed at assessing the CPR skills of a group of physical and health education student teachers (the potential professional teachers) at the University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. It was hypothesized that: (1) their pre-training CPR skills would not be statistically poor; (2) their post-training CPR skills would not be significantly different from their pre-training CPR skills.

2. Materials and Methods

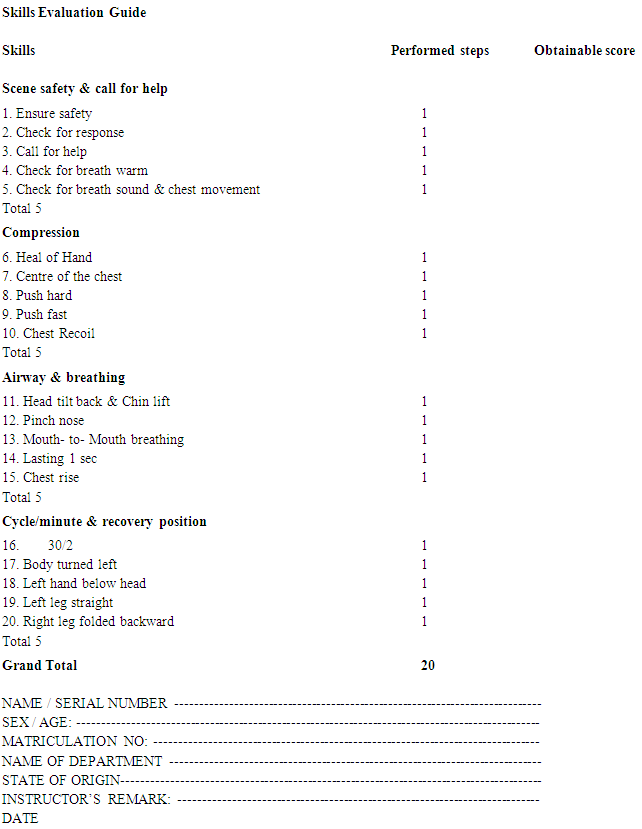

- A quasi-experimental cohort study design involving one hundred and fifty two (152) 200-level undergraduate physical and health education students (student teachers) in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria was carried out.The study took place in June, 2017. The study sample of the student teachers in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education were admitted in 2015 and are studying to graduate with Bachelor of Education Degree (majoring in either Health Education or Human Kinetics). They are being trained primarily to become teachers in primary and secondary schools. These student teachers are from different parts of Nigeria.The following null hypotheses were generated and tested:Ho1: That the pre-training CPR skills of the student teachers would not be statistically poorHo2: That their post-training CPR skills would not be significantly different from their pre-training CPR skills.Stage 1 (Pre-training)A questionnaire containing a section for the demographic data of the participants and a section having the modified AHA ‘Skills Evaluation Guide’ to assess their pre-training cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills was used. Prior to the training on CPR, all of them were shown a scenario of a victim of cardiac arrest using the manikin and asked to demonstrate what they would do in such a situation to save the life through cardiopulmonary resuscitation.The Skills Evaluation Guide (SEG) was used to score the student teachers’ pre-training skills while the questionnaire was used to obtain the demographic data of the participants and their theoretical knowledge of CPR.Stage 2 (Training and Immediate Post-training)The teaching on CPR was carried out for 60 minutes using American Heart Association (AHA) CPR guideline which is available online. Their skills were evaluated using modified AHA Evaluation Guide involving four domains – 1. Scene Safety & Call for Help (S), 2. Chest Compressions (C), 3. Airway & Rescue Breaths (B) and 4. Cycle / min & Placement of victim in the correct Recovery Position (R) (Appendix). After the CPR teaching and training session, they were then asked to individually attend to the same scenario given to them before the training and they were scored. Two of the initial student teachers (participants) were not available for the post-training CPR skills assessment, giving the final sample size of 150 participants.The lead researcher, who is an American Heart Association (AHA) - certified CPR instructor did the training and assessed the CPR skills of the participants. The CPR skills were grouped into the four domains. The process of training them on hands-on and re-assessment took another 3 hours.Determination of Poor and Good CPR SkillsFor each of the four (4) domains of the CPR skills, 50% is considered acceptable and any score less than that is considered poor CPR Skills while 50% and above is considered good CPR skills.Statistical AnalysisThe Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze the data. In addition to descriptive statistics, one sample and two sample T-tests statistics were employed in the analysis and testing of the null hypotheses with significance level set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

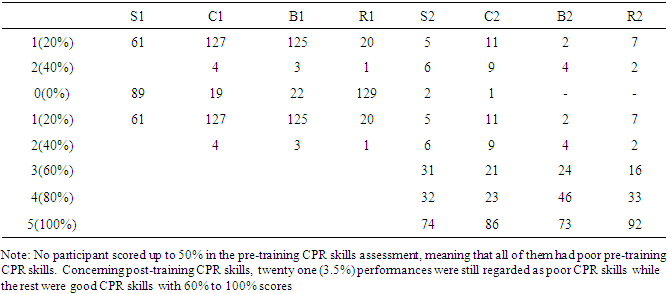

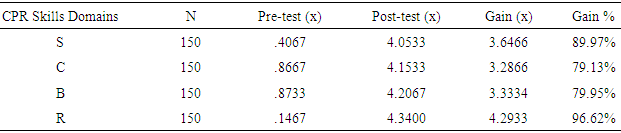

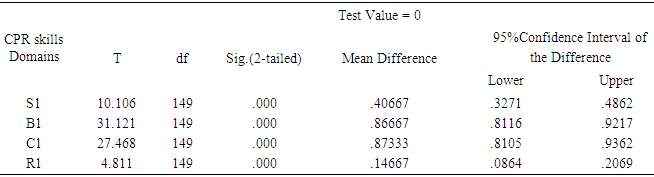

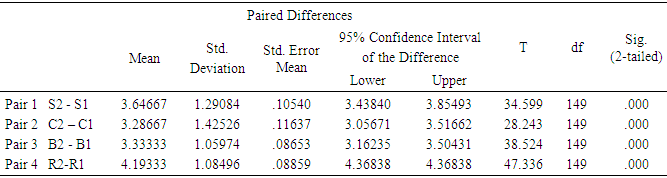

- The final cohort of one hundred and fifty (150) participants in this study was made up of 56 (37.33%) male and 94 (62.67%) female, age range of 17-28 years and mean age of 21.11 ± 2.40 (SD).In Table 1 is the CPR skills performance of the participants in the four domains assessed in percentage with none of the participants having up to 50% skills performance during the pre-training stage while twenty one (21) performances ( 6 for poor skills in scene safety and call for help, 9 in chest compressions, 4 in the procedure for airway patency and giving of rescue breaths and 2 for cycle/min and placement victim in the correct recovery position) still belonged to the 40% of the CPR skills after the training. The rest of the performances in the four CPR skills domains belonged to 60% to 100% scores after the CPR training.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Despite the significantly poor pre-training CPR skills of the participants in this Nigerian study, the participants had significantly improved CPR skills after the CPR training with 60% to 100% scores unlike in their pre-training CPR skills where all of them had significantly poor CPR skills. However, this Nigerian study, 3.5% of the performances (involving all the skills domains) after the training were still poor because they were found as 40%. This is comparable to a recent and the only similar study involving Nigerian primary and secondary school teachers CPR skills where all the teachers had ‘good CPR post-training skills’ [24].Similar study [22] on the CPR skills of some Nigerian secondary school students reported significantly improved post-training CPR skills as in the present study. These findings are encouraging for the advocacy of introducing CPR teaching and training into the Nigerian school curriculum.In Saudi Arabia, the study [17] involving 305 teachers with 75.4% as males and 66.5% between the ages of 31 and 50 had 35.7% of the teachers with earlier CPR training; but still had CPR knowledge and skills low (mean = 4.0, sd = 1.62). According to that report, the average scores did not differ between those who had training and those who did not. They concluded that in Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia secondary school teachers lacked CPR training and hence have little knowledge or skills and those teachers were willing and desirous to have more CPR training available to them. The report further stated that if health officials should provide future training, teachers could serve the community better. Although the Nigerian study showed very poor pre-training CPR skills, their post-training CPR skills improved very significantly. It should be noted here that none of the Nigerian student teachers had any previous.CPR training before this study. Also, it is interesting to note that more female student teachers were involved in our Nigerian study (62.67%) compared to the Saudi Arabia study with more males. This could be due to the religious differences between Al Qassim in Saudi Arabia having mainly Muslims and Rivers state in South-south Nigeria having mainly Christians.According to Mpotos et al [16], a total of 4273 teachers participated in their study (primary school n = 856; secondary school n = 2562; higher education n = 855). Of all respondents, 59% had received previous CPR training with the highest proportion observed in primary schoolteachers (69%) and in the age group 21-30 years (68%). Sixty-one percent did not feel capable and was not willing to teach CPR, mainly because of a perceived lack of knowledge in 50%. In addition, 69% felt incompetent to perform correct CPR and 73% wished more training.Feeling incompetent and not willing to teach was related to the absence of previous training. Primary schoolteachers and the age group 21-30 years were most willing to teach CPR. They concluded that although many teachers mentioned previous CPR training, only a minority of mostly young and primary schoolteachers felt competent in CPR and was willing to teach it to their students. In our present Nigerian study, our cohort group has a comparable age group having the age range of 17-28 with mean age of 21.11 ± 2.40 (SD). It would seem that the younger teachers are more interested in teaching as they are more competent in CPR.This quasi-experimental Nigerian study is similar to that reported by Navarro-Paton et al [25] which assessed the effectiveness of the three teaching programmes for CPR training - traditional course, an audio-visual approach and feedback devices and concluded that the feedback devices gave the best outcome. The present Nigerian study, being the first Nigerian study that assessed the CPR skills of student teachers, combined all the programmes.Meanwhile, del Pozo et al [26] showed that incorporating the song component in the cardiopulmonary resuscitation teaching increased its effectiveness and the ability to remember the cardiopulmonary resuscitation algorithm. Our study highlights the need for different methods in the cardiopulmonary resuscitation teaching to facilitate knowledge retention and increase the number of positive outcomes after sudden cardiac arrest. Our future Nigerian studies might try to find out which approach would be the most effective in our environment. The Society of Health and Physical Educators (SHAPE), America in their Guidance Document stated that the health teacher in schools should ensure that the curriculum is organised to foster development skills to proficiency and the curriculum includes multiple opportunities for practising health-related skills [27]. It has one of its core principles as encouraging best practice in health education which includes having certified and / or highly trained health educators teaching health at all levels. One of the strengths of the present Nigerian study is that it is fairly representative and helping to adequately prepare our future school teachers to be better equipped to provide needful health-related education for our children. In addition, it is a form of advocacy for introduction of CPR teaching and training into the Nigerian school curriculum.

5. Limitation of the Study

- Although the University of Port Harcourt is a Federal University and the students are usually drawn from different parts of the country and by extension the student teachers involved in this study, not every State of the Federation in Nigeria is represented. Therefore, the study sample cannot be said to be a perfect representative sample of the future teachers in Nigeria.

6. Conclusions

- Although the participants (student teachers) in this Nigerian study had significantly poor pre-training CPR skills, their post-training CPR skills were encouragingly significantly improved and better than their pre-training CPR skills.

7. Recommendations

- More related studies should be targeted at the potential school teachers (student teachers) in other Nigerian Universities and other tertiary institutions so as to create the needed awareness, increase advocacy and provide adequate training on CPR to them in preparation for their future roles in the teaching / training and incorporation of CPR into the Nigerian school curriculum.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to appreciate Prof C O Onyeaso (Professor of Orthodontics) for his inspirational guidance and encouragement during this study.

Appendix

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML