-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2017; 7(2): 25-32

doi:10.5923/j.health.20170702.02

Behavioural and Socio-demographic Predictors of Cardiovascular Risk among Adolescents in Nigeria

Eyitayo E. Emmanuel 1, Oluwole A. Babatunde 2, Olusola O. Odu 1, Adeniran S. Atiba 3, Kabir A. Durowade 4, David D. Ajayi 5, James O. Bamidele 1, Bayo D. Parakoyi 4

1Department of Community Health, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

2Department of Epidemiology, University of South Carolina, USA

3Department of Chemical Pathology, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

4Department of Community Medicine, Federal Teaching Hospital, Ido Ekiti, Nigeria

5Department of Chemical Pathology, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Eyitayo E. Emmanuel , Department of Community Health, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

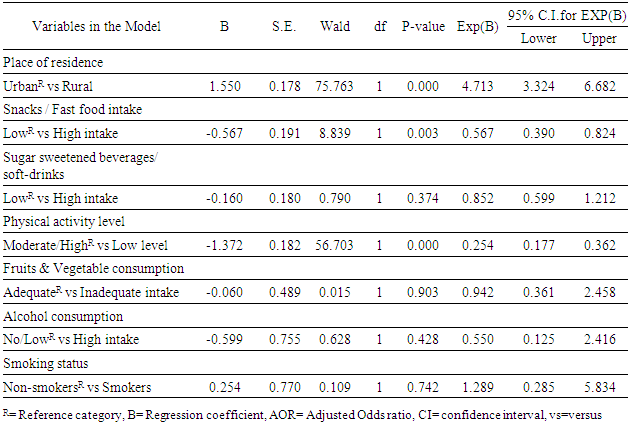

Background: Cardiovascular disease in adulthood could have its origin in childhood and adolescence through the development of certain risk factors early in life. This study aims to determine the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, and identify it socio-demographic and behavioural predictors among adolescents. Methodology: The study was carried out in Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. It employed a cross-sectional analytical study design. A total of 800 In-school adolescents (age 10-19yrs) were selected from secondary schools across the State using Multistage sampling technique. Modified STEP instrument was used for data collection. SPSS version 20 was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square test and Multiple logistic regression were used to assess the association. Level of significance was set at P<0.05. Results: A total of 737 adolescents completed the study (Response rate of 92.1%). About 10.6% of the respondent were hypertensive, 7.1% were overweight/obese, 9.7% had impaired fasting glucose, 24.6% had abnormal lipid profile, while about 36.4% of the respondents had ‘at least one CVRF’ (AOCVRF). Place of residence (Adjusted ORurban =4.7, 95% CI=3.3 to 6.7), Intake of snacks/fast food (Adjusted ORLow intake=0.6, 95% CI=0.4 to 0.8) and level of physical activity (Adjusted ORHigh=0.3, 95% CI=0.2 to 0.4) were the significant predictors of cardiovascular risk. Conclusion: More than a third of the adolescents had at least one cardiovascular risk factor, while levels of physical activity, intake of snacks/fast-food and place of residence were its independent predictors.

Keywords: Cardiovascular risk factors, Adolescents, Physical activity, Hypertension, Overweight/Obesity

Cite this paper: Eyitayo E. Emmanuel , Oluwole A. Babatunde , Olusola O. Odu , Adeniran S. Atiba , Kabir A. Durowade , David D. Ajayi , James O. Bamidele , Bayo D. Parakoyi , Behavioural and Socio-demographic Predictors of Cardiovascular Risk among Adolescents in Nigeria, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 25-32. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20170702.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is estimated that about 30% of all global deaths are due to CVD [1]. CVD is rapidly emerging as a public health challenge in developing countries accounting for 80% of deaths from chronic diseases and 87% of related disability currently recorded in these countries [2]. This situation has been predicted to grow worse [3]. The rise in CVD is mostly due to a rise in key risk factors, mainly hypertension and overweight/obesity [4]. The rise in the prevalence of overweight/obesity has been largely attributed to the more sedentary lifestyle and nutrition transition. There has been a shift in the patterns of diet and physical activity towards unhealthy foods higher in fat, sugar and energy, and low in fruit and vegetable and fibres, alongside more sedentary lifestyles [5]. Although overt manifestations of CVD such as heart attack and stroke, do not usually emerge until adulthood, cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, overweight/obesity, pre-diabetes/diabetes and dyslipidemia are often present during childhood and adolescence [6-8]. There is a growing evidence demonstrating that CVD risk factors present during childhood/adolescence may persist into adulthood- a phenomenon known as ‘tracking’ of the risk factors [9]. Recent report estimated that about 34% of adolescents in the United States of America were overweight/obese, 23% had impaired fasting glucose/diabetes, about 22% had abnormal lipid profile, while about 14% were hypertensive [8]. However, previous studies in Nigeria has reported a prevalence range of 0.1-17.5% for adolescent hypertension [4, 10-13], about 0 -9.4% for obesity [14-17], about 17% for impaired fasting glucose [18] and about 33% for dyslipidemia [19]. Most of the previous studies in Nigeria have concentrated on a single cardiovascular risk factor and have also neglected biochemical analysis of the lipid profile and fasting blood sugar of the adolescents [11, 20, 21]. This biochemical analysis which has been omitted in most of the previous studies, has been recommended by the WHO as an important step in the surveillance of cardiovascular risk factors in developing countries [22], especially when the full cardiovascular risk profile is desired.The objective of this study is to determine the prevalence as well as the clustering of CVRFs among adolescents in Ekiti State. It will also identify the socio-demographic and behavioural predictors of the presence of cardiovascular risk among adolescents. It is expected that the findings of this study will help to guide the development of health policy and preventive strategies that are essential towards combating the menace of cardiovascular disease in Nigeria.

2. Methodology

- The study was carried out in Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. There are 16 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in the state. The study population consisted of in-school adolescents (age 10-19yrs) selected from public and private secondary schools across the State. Cross-sectional analytical study design was used for the study. A total of 800 adolescents were recruited for the study using Multistage sampling technique. In stage-1, the sixteen LGAs in the state were stratified into predominantly urban and predominantly rural LGAs and two LGAs were picked from each stratum. In stage-2, two secondary schools were selected from each of the LGAs selected in stage-1. While in stage-3, 100 consenting adolescents were selected from each school. Respondents were apparently healthy secondary school adolescents between the ages of 10-19 years. Only adolescents who assented to participate and presented a written informed consent from their parents were included in the study. Pregnant adolescents, those on hormonal contraceptives and those on chronic steroid therapy, were excluded from the study. Interview was facilitated by trained interviewers.The anthropometric measurements were taken by nurses and medical doctors. Height was measured using stadiometer, while weight was measured using electronic weighing scales Seca model. Weight was recorded in kilograms while height was recorded in metres. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight (in Kg) by the square of the height (in metres). BMI greater than or equal to the 95th percentile for age and sex was considered as obesity, while BMI between 85th and less than 95th percentile was regarded as overweight [23, 24]. Blood pressure (BP) of each subject was measured throughout the study with the same brand of an electronic sphygmomanometer (OmronRHEM-907) of appropriate cuff sizes in sitting position using the right arm after about 15 minutes rest. Three consecutive measurements were obtained 5 minutes apart and the values were expressed in millimeter of mercury (mmHg). Subjects were advised to fast for 10 -14 hrs overnight. About 7.5 mls of venous blood was drawn using aseptic procedure, 2.5 mls and 5mls were subsequently dispensed into fluoride oxalate and lithium heparin specimen bottles respectively. Blood sample from each of the bottles was centrifuged at 3000g for about 5 minutes. Plasma from lithium heparin bottle was kept frozen till analysis and used for the analysis of lipid profile (Fasting Plasma Total Cholesterol, High Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol and Triglyceride. Low Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol was calculated using Freidwald,s formular [25], Plasma from fluoride oxalate bottles was used for fasting plasma glucose. Plasma glucose and lipid profile were analysed using ready to use commercial kits manufactured by Randox laboratotry, Aldren, USA.Ethical approval for the study was obtained at the Federal Teaching Hospital, Ido-Ekiti. Parental consent was obtained in addition to permission of the adolescents and the State Ministry of Education prior to the study.

2.1. Outcome Measures

- Participant were described as hypertensive if either or both the systolic and diastolic BP is / are greater than the 95th percentile for age, sex and height or if they were on any antihypertensive drugs during the time of the survey [21]. Fasting plasma glucose from 5.6mmol/l to 6.9mmol/l were classified as impaired fasting glucose, while values greater than or equal to 7mmol/l was regarded as diabetic [26]. BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile for age and sex was considered as overweight/obesity, while BMI between 85th and less than 95th percentile was regarded as overweight, BMI equal or greater than the 95th percentile for age and sex was regarded as obesity [27]. Total cholesterol less than 5.1mmol/l, triglycerides less than 1.7mmol/l, LDL-C less than 3.3mmol/l and HDL-C greater than 1.0mmol/l were regarded as normal [28]. Communities with population greater than 50,000 were regarded as urban, while those with population less than 20,000 were regarded as rural.Physical activity level was determined using the scores from the physical activity section of the questionnaire (this section was adapted from the Fels physical activity questionnaire). Respondents were classified based on the total score into either low physical activity level if they scored less than 8, or moderate/High level if they scored 8 and above [21, 29]. Respondents were classified as smokers (current daily and occasional smokers), or non-smokers [30]. Daily consumption of at least a serving of fast foods/snacks daily on 3 or more days/week was regarded as high intake [31]. Consumption of at least a serving of sugar-sweetened beverages/soft drinks daily on 3 or more days/week was regarded as high intake of SSB/soft drinks [32, 33]. Daily consumption of five or more servings of fruits and vegetables was classified as ‘adequate’, while consumption of less than five servings of fruits and vegetables daily was classified as ‘inadequate’. Those with intake of 2 or more standard units of alcohol daily or intake of 5 or more unit on a single occasion were regarded as High/ at risk drinkers while, those with no history of alcohol consumption and those with intake less than 2 units of alcohol daily were regarded as No/Low risk group [34]. SPSS version 20 was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square test was used to assess the association between socio-demographic/behavioural variables and the presence of ‘at least one cardiovascular risk factors’ (AOCVRF), while multiple logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of the presence of AOCVRF.

3. Results

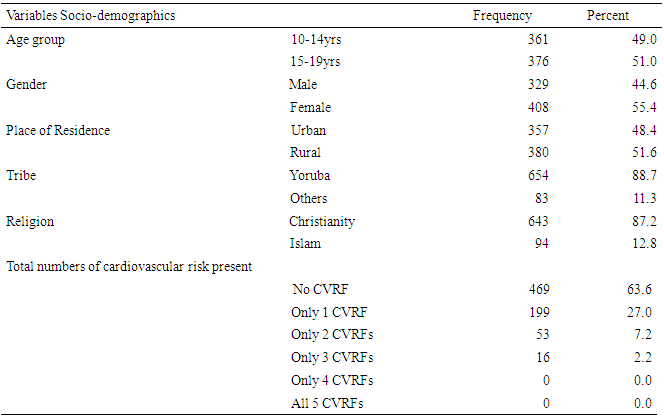

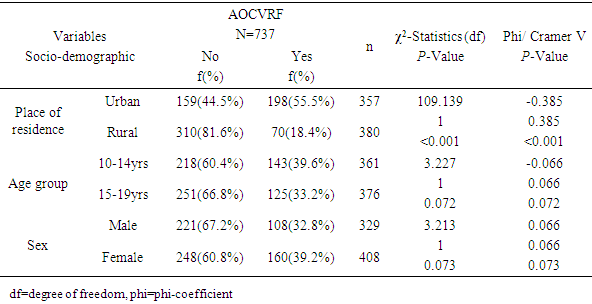

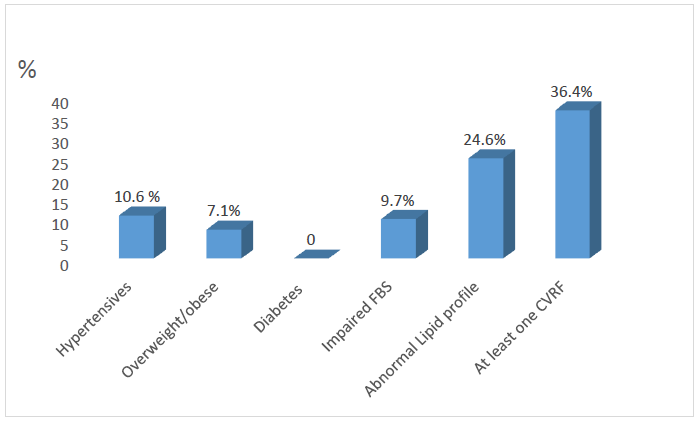

- A total of seven hundred and thirty seven adolescents participated in the study (Response rate of 92.1%). About 49% of the respondents were in the age group of 10 to 14years, while about 55% were females. As expected, majority (88.7%) of the respondents were Yoruba while about 87.2% were Christians. About 51.6% were residing in rural areas as shown in table 1.As shown in figure 1, about 10.6% of the respondent were hypertensive, 7.1% were either overweight or obese, while none of the participants had diabetes. However, about 9.7% of respondents had impaired fasting glucose, while abnormal lipid profile was reported in about 24.6% of the respondents. Summarily, about 36.4% of the respondents had AOCVRF.

| Figure 1. Prevalence of the major cardiovascular risk factors (n=737) |

|

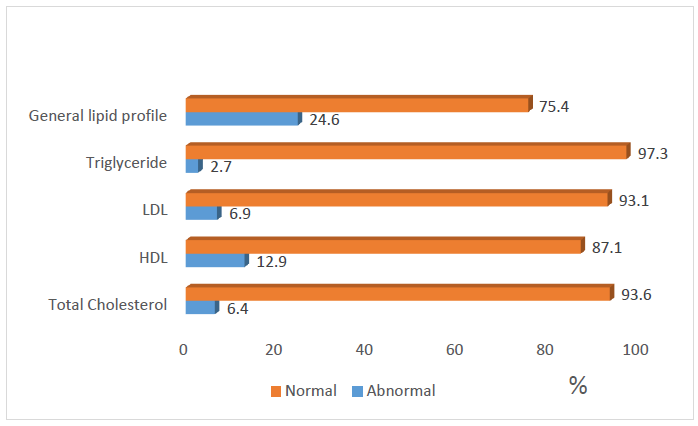

| Figure 2. Distribution of the respondents Lipid profile |

|

|

|

4. Discussion

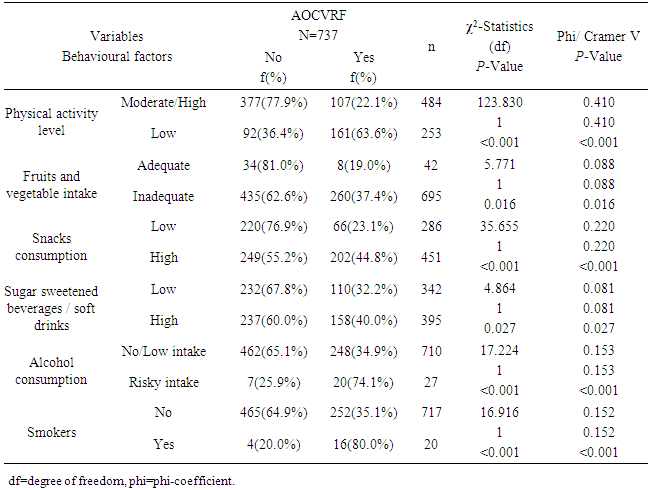

- The prevalence of hypertension in the study was 10.6% which is within the prevalence range (0.1-17.5%) reported by most of the previous studies among adolescents in Nigeria [11, 13, 35]. This prevalence is similar to the rate reported among Mexican adolescents [36]. The implication of this finding is that the prevalence of hypertension in this study is high and it calls for concern. Since hypertension has been shown to track with age, as adults, these adolescents with hypertension will have a higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease if left undiagnosed/ untreated [36]. The prevalence of overweight/obesity (BMI≥85th percentile for age and sex) was found to be 7.1% in this study, while 1.9% of the respondents had BMI≥95th percentile for age and sex (obesity). This is consistent with most of the previous studies on the prevalence of obesity among Nigerian children and adolescents which gave a range between 0 to 4% [14-16]. Overweight/obesity especially in childhood and adolescence, is seeing mainly as the fuel for the epidemic of many of the chronic non communicable diseases [37]. Diabetes was not found among the adolescents. However, the prevalence of impaired glucose was 9.7%. This prevalence is lower than the results obtained recently by Jaja et al in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, where they got a prevalence of 17% for impaired fasting glucose among adolescents in Port Harcourt. The difference could be due to the fact that Port Harcourt is an urban city whereas the current study was done in rural and urban areas of Ekiti State [18]. Abnormal lipid profile was found in almost a quarter (24.6%) of the respondents. The prevalence of hypercholesterolemia in this study was 6.4% and that of low HDL was 12.9%. The commonest lipid abnormality in this study was low HDL, this is in agreement with most other studies in Nigeria and other countries [19, 38, 39]. However, it is note-worthy that the prevalence of HDL in these studies above were higher than that obtained in the present study. The observed difference may be due to lifestyle differences between the study groups and may be a subject of subsequent studies. Odey et al concluded that the prevalence of abnormal lipid profile was rising towards values seen in developed countries, hence this is a wakeup call to action [19]. A major finding in this research was the presence of AOCVRF in almost a third (36.4%) of the respondents. Though this prevalence is rather high, it is however lower than what was reported by Odunaiya et al in their study among adolescents in a neighbouring state [40]. Studies have suggested that the high prevalence of CVRFs among adolescents could be due to the adoption of unhealthy lifestyles in childhood and adolescence [14, 15, 21]. This study also revealed that more than half of those residing in the urban areas had at least one cardiovascular risk factor compared to only about one fifth seen in the rural area (χ2=109.139, P<0.001). This report that CVRFs are commoner in urban population is in agreement with the reports from most of the other studies. It thus implies that urbanization and westernization with the consequent changes in the traditional lifestyle which are more prominent in urban areas could be the major drivers of increasing prevalence of cardiovascular risk. Concerning behavioural factors however, about half (47.6%) of the respondents had low level of physical activity in this study. This is slightly higher than the average prevalence of physical inactivity reported in Nigeria and some other countries [37, 41] but lower than the average prevalence of physical inactivity in high-income countries [30, 42, 43]. It was also shown that those with low levels of physical activities were more likely to have AOCVRF compared to those with moderate-high level of physical activity. Above findings are in agreement with some of the previous studies that physical inactivity increases the chances of developing cardiovascular disease and that sedentary lifestyle is becoming more prevalent among adolescents [1, 44-47]. The strength of this study is the assessment of multiple cardiovascular risk factors including biochemical factors such as lipid profile and plasma glucose, in the same individual. The non-inclusion of the out of school adolescents may reduce the external validity of this study and is therefore a limitation of this study.

5. Conclusions

- Almost a third of the adolescents had at least one cardiovascular risk factor, while the prevalence of the various CVRFs were generally high in the study. Identified correlate of the presence of cardiovascular risk in the adolescents were Low levels of physical activity, high intake of snacks/fast-food and urban residence.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML