-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2016; 6(4): 62-66

doi:10.5923/j.health.20160604.03

Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of Hepatitis B Virus in Dera Ismail Khan Division

Jabbar Khan1, Niamatullah Khan1, Atta ur Rahman1, Shahid Niaz Khan2, Hamidullah Shah3, Rahman ud Din4

1Department of Biological Sciences, Gomal University D.I.Khan, KPK, Pakistan

2Department of Zoology, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, KPK, Pakistan

3Department of Histopathology, Post Graduate Medical Institute, Lady Reading Hospital, Peshawar cant. KPK, Pakistan

4Mufti Mehmood Teaching Hospital, D.I.Khan, KPK, Pakistan

Correspondence to: Jabbar Khan, Department of Biological Sciences, Gomal University D.I.Khan, KPK, Pakistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Hepatitis B is potentially life threatening liver infection, which leads to millions of deaths annually. Serological and molecular assays for hepatitis B virus are the major diagnostic tools. We were here interested to see whether or not alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is the mirror image of quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR). This study thus covers the sero-biochemical and molecular characterization of 565 Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HbsAg) positive patients to see any correlation between ALT and qPCR of patients. All the patients were subjected to Hepatitis B Envelop Antigen (HbeAg), ALT and qPCR during the period of March to July-2015. We found that 462 patients were HbeAg negative and 103 patients were HbeAg positive. Of the HbeAg negative patients, 32.57% possessed more than 20000 IU/ml DNA and 9.30% were having more than 100 U/L ALT, showing positive correlation between ALT and viral load thus indicating low infectivity ratio. Similarly, of the total 103 HbeAg positive patients, 85.80% patients had more than 20000 IU/ml DNA and 60.19% patients possessed more than100 U/L ALT. This again showed a strong correlation between ALT and viral load of the patients, indicating the active replication of virus.

Keywords: Alanine aminotransferase, Hepatitis B Surface Antigen, Hepatocytes, Alkaline phosphatase

Cite this paper: Jabbar Khan, Niamatullah Khan, Atta ur Rahman, Shahid Niaz Khan, Hamidullah Shah, Rahman ud Din, Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of Hepatitis B Virus in Dera Ismail Khan Division, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 62-66. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20160604.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) can cause both acute and chronic liver diseases [1]. Approximately 8% of the world's population has been infected with HBV, and about 5–6% are persistent carriers of HBV [2]. The clinical presentation ranges from subclinical to symptomatic and, in rare instances, fulminant hepatitis [3], but with few or no symptoms in case of perinatal or childhood infection, although it has a high risk to become chronic. Very limited numbers of medications are available to effectively treat chronic hepatitis B [4].HBV causes noncytocidal, chronic infection to hepatocytes and this is one of the reasons for chronic HBV infections [5]. Viruses are continuously shed by hepatocytes into the bloodstream. Moreover, hepatocytes possess long-life, having 6 to 12 months or more. Hence, in the absence of a robust immune response, the combination of long-lived non-dividing host cell and a stable virus-host relationship virtually ensures the persistence of an infection [6].Two biochemical markers of hepatocellular damage are AST (also termed as SGOT) and ALT (also called SGPT) [7, 8]. AST is found basically in liver, kidney, heart and skeletal muscle, while ALT is found in liver and kidney, with very little amounts in heart and skeletal muscle [9, 10]. The serum ALT and AST levels reflect the extent of hepatocellular damage and are routinely used for assessing liver function. AST and ALT activity in liver are about 7,000 and 3,000 times serum activities, respectively and ALT is exclusively cytoplasmic [10, 11]. In adult males, AST and ALT activities are significantly higher than in females. AST activity is slightly higher than ALT, upto 15 and 20 years of age in males and females. In case of adults, AST activity tends to be lower than that of ALT until age 60 [9, 12]. Increased ALT activity is the most important indication of liver disease. Moreover, increased AST activity is commonly found in liver disease [12-15]. Hence, the serum levels of both ALT and AST are usually high in patients having chronic hepatitis, although a small number of patients with histological chronic hepatitis have transiently normal aminotransferase levels [16]. The elevation of more than 400 IU/L are common in the case of untreated sever chronic viral hepatitis [17]. Another important biochemical marker of hepatocellular damage is serum alkaline phosphatase (AP), involved in transport of metabolites across cell membranes. It is found in a decreasing order of abundance, in placenta, ileal mucosa, kidney, bone, and liver [18]. Elevation of AP in the setting of liver disease results from increased synthesis and release of the enzyme into serum rather than from impaired biliary secretion. The cholestatic liver diseases primarily cause elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase values [19, 20], while in about 90% of those patients with HBV; the AP value is fond normal. [21].Pakistan is highly endemic with HBV infection [22]. More than nine million people are infected with HBV [23] and infection rate is still on a steady rise [23, 24]. The epidemiological studies highlighting the prevalence of HBV are very much confined to the hospitalized patients [24, 25], and so, very few population studies are there to determine the exact infected population in different areas. Risk factors that spread Hepatitis B include the number of therapeutic injections received per year, use of improperly sterilized invasive medical devices including surgical and dental instruments, circumcision and cord cutting instruments, and re-use of razors by street barbers. Horizontal transmission in early childhood is an important mode of transmission. A proportion of children become HBV positive from HBsAg-positive siblings and this risk increases with age. Vertical transmission from infected mothers to their neonates is also a contributing factor in Pakistani population [25, 26].Here the main objective of this research work dealing with sero−biochemical and molecular characterization of HBV in D.I.Khan district is see whether or not there is any correlation between ALT and qPCR in HBsAg positive patients. In this regard, blood samples of in 565 HBsAg positive patients were processed for both serological and biochemical markers and their viral load was determined through qPCR for determining any possible correlation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Sample Collection

- The collection of blood sample was done in gastroenterology section of Mufti Mehmood Teaching Hospital, D.I.Khan. Ten ml blood was collected from each patient for serological, biochemical and qPCR studies. Each sample of blood was divided into two parts. From one 5ml of blood, serum was isolated to be used for serological and biochemical studies while the other 5ml of blood contained ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), from which, DNA was extracted that was to be used for qPCR analysis. Both the serum samples and extracted DNA samples were frozen at -20°C.

2.2. Serological Markers

- The collected serum samples were analyzed for the serological markers of HBV, such as HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBeAb by means of the Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) (DiaPro Diagnostic Bioprobes; Milano, Italy and Biokit, Spain) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Biochemical Markers

- The liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was quantitatively measured using Pars Azmoon kit (Tehran, Iran) based on the kit instruction.

2.4. Viral DNA Extraction

- DNA of HBV DNA was extracted from the serum of each patient for carrying out PCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions using QIAmp DNA mini-extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

2.5. DNA Quantification of HBV

- Quantitative measurements of HBV DNA were done by real-time PCR using the Artus Light Cycler HBV DNA kit (Qiagen; Hilden, Germany); as per kit instructions and Light Cycler 2.0 instrument Real-Time PCR (Roche, Germany).

3. Results

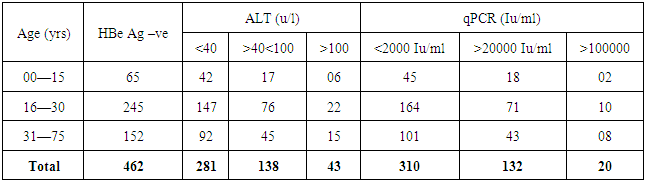

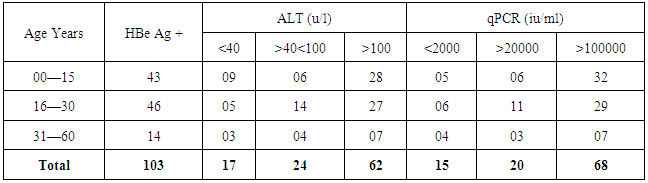

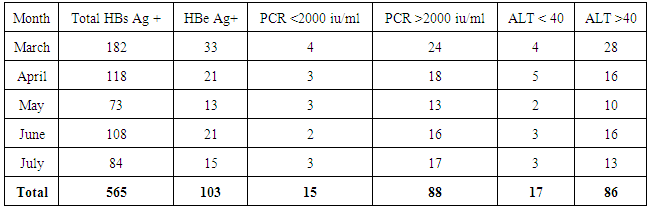

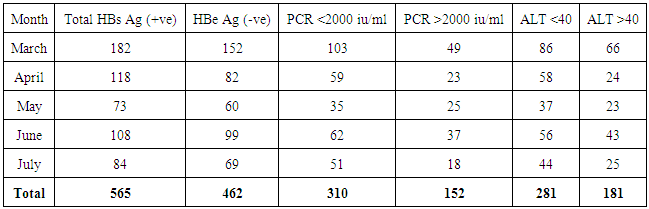

- We address the health−concerned implications of HBV in 565 HBsAg positive patients of Dera Ismail Khan Division. Our goal was to determine the reliable relationship between Sero-biochemical and molecular characterizations of HBV patients. To achieve that purpose, we carefully studied the serology and biochemistry of patients of the present study through commercially available kits. We then molecularly characterized the patients through PCR. The present ages of these patients ranged from 01 year to 75 years. Total 565 individuals were screened for HBsAg, HBeAg, and ALT abnormalities. The said patients were then molecularly characterized through quantitative PCR (qPCR) for viral load. Interestingly, almost all the HBsAg positive patients were positive for qPCR.We found that HBeAg negative Patients show low infectivity in relation to ALT and qPCR (Table 1) as out of 462 patients, 9.3% have more than (>) 100 u/l ALT (SD 15.75) and 4.3% have >100000 IU/ml (SD 7.48) DNA. We also observed that the young age (16—30 years) is significant in spreading and prevailing the disease in a community (Table 1).In contrast to HBeAg negative patients, the HBeAg positive patients showed high infectivity ratio in correlation to ALT and qPCR. Here we found that out of 163 HBe Ag positive patients, 60.19% patients were having >100 u/l of ALT (SD 11.54) and 66.01% patients had >100000 IU/ml (SD 13.65) (Table 2). Again here, the maximum numbers of patients were found with the young age of 16 to 30 years of age that was alarming to our community. Hence, we found a strong correlation of ALT to qPCR in case of HBeAg positive patients, showing the active replication of virus. During this five months study (March to July−2015), total of 565 HbsAg positive patients (SD 42.57) were characterized for HBV Serology, ALT and qPCR. We found that only 103 individuals were HBeAg positive (SD 7.79) (Table 3). Here we showed that 85.4% of the positive cases had more than 2000 IU/ml (SD 4.03) and 83.4% of the cases possess more than 40 ALT (SD 6.84) (Table 3). These results clearly showed high correlation of HBeAg positive patient in terms of qPCR with respect to ALT.Similarly, in the same five months study (March to July−2015) total 565 HbsAg positive patients were analyzed for HBV Serology, ALT and qPCR. We found that 462 cases were found HBe Ag Negative (Table 4). Here we showed that only 32.9% of the cases had more than 2000 iu/ml (SD 12.52) and 39% of the cases possessed more than 40 ALT (SD 18.60). This indicated high correlation of HBeAg negative patient in terms of qPCR and ALT thus determining low infectivity or carrier frequency of HBV.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Hepatitis B infection is a worldwide health problem and is continuously creating serious problems in developing countries like Pakistan [22, 23]. The current study was conducted with the main aim to find out the correlation between serological, biochemical and molecular parameters among HBsAg positive HBV patients in D.I. Khan Division of KPK.The average values of ALT for patients in this study is (52 U/L), the results showed that ALT will be slightly raised in chronic HBV infection, which are in consistent with the previous results [12, 28], indicating that in case of chronic HBV infection, 89% of the patients yielded continuously normal ALT levels, while 11% showed at least one ALT value above the normal levels. Other reports [13, 28] showed that, the serum ALT levels are constantly normal in 57.4% of HBV- PCR positive patients while 42.6% of the patients showed ALT values above the normal level. Moreover, the results of our present study are in consistent with to the study done in Turkey, showing that serum mean ALT values were three to six times higher in chronic hepatitis B [27]. Previous reports [27] also showed the consistent higher values of ALT and AST with chronic hepatic injury. A small number of individuals, having only elevated ALT were found to possess liver disease [27]. It has also been described that determination of ALT alone can successfully predict viral load in chronic HBV patients. In the present study, patients with high serum HBV DNA have been found to have a high serum ALT activity.Regarding the molecular characterization, it was found in the present study that more than 90% of HBeAg-positive patients had serum HBV DNA levels that could be detected by non-PCR assays, which have detection limits of 105 copies/mL. In this study, the correlation between HBV DNA and ALT levels in HBeAg-positive patients was quite strong. In certain cases, it was poor, probably because of immune tolerance secondary to perinatal infection.The National Institutes of Health workshop on management of hepatitis B proposed that a serum HBV DNA level of 105copies/mL be used to differentiate chronic hepatitis B from an inactive carrier state. Our results showed that HBV-DNA value above 105copies/mL would exclude all inactive carriers but also 45% of patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis if testing were only performed at presentation and 30% if testing were performed on 3 occasions. Given the variable course of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, retesting on more than one occasion helps in differentiating patients with HBeAg- negative chronic hepatitis from inactive carriers, but no single HBV DNA value reliably differentiates these 2 groups. In accordance with other reports, we found that serum HBV DNA remained detectable in the vast majority of inactive carriers, but HBV DNA levels tend to be lower and remain stable over a 5-year follow-up period. We found that serum HBV DNA levels were very high (105-120 copies/ml) in majority of HBeAg-positive patients.This study showed that HBV affected almost all the age groups of this area. The prevalence in children of age 1 to 15 reached a peak of 13.23%, while, in people having the age 16 to 30 years, it was about 16.34%. In contrast to these figures, the prevalence declined to 10.16 and 5.62% in people with age between 31 to 45 and 46 to 60 years respectively. While old >60 age group were very less frequently 2.15% infected by HBV infection. This means that age was also one of the factors in the prevalence of hepatitis B infection. This high prevalence among the young age groups can be attributed to their frequent exposure to risk factors and also, most probably, due to their greater exposures and interaction in society as compared to children and people of old ages.Hence, the HBe Ag Positive patients with high ALT level and viral load (more than 20000 iu/ml) are suggested to have viral therapy.

5. Statistical Analysis

- Results are presented as percentage and standard deviation wherever necessary

6. Conclusions

- HBV is spreading in D.I.Khan district of KPK at alarming speed, hence, public awareness programs and vaccination on large scale need to be managed to stop the further spread of the disease.

7. Recommendations

- 1. HBeAg-positive patients with HBV DNA >20,000 IU/ml and persistently normal or minimally elevated ALT should not be recommended for antiviral therapy and should be monitored every 3 months. If moderate or greater inflammation is detected on biopsy, the patient can be considered for treatment.2. HBeAg-positive patients with HBV DNA levels of <20,000 IU/ml and normal ALT do not require treatment but should be monitored every 3–6 months.3. HBeAg-negative patients with HBV DNA levels of <2,000 IU/ml and normal ALT are most often inactive HBsAg carriers and do not need any antiviral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We acknowledge the very kind cooperation of the staff members of medical ward of Mufti Mahmood teaching hospital, D.I.KHAN, KPK, Pakistan.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML