-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2016; 6(4): 57-61

doi:10.5923/j.health.20160604.02

Observations of Stress and Health: A Micro Investigation of Perception among University Students

Michelle Calvarese

Department of Geography, California State University, Fresno, Fresno, California, United States

Correspondence to: Michelle Calvarese, Department of Geography, California State University, Fresno, Fresno, California, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

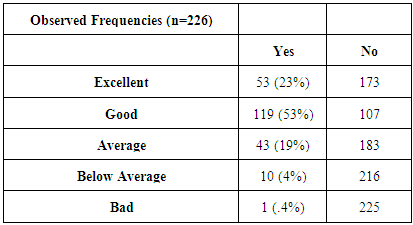

This study analyzed how university students perceived their level of stress, as well as their overall health. Using a survey instrument, the majority of students rated their stress level as average. The primary causes of stress were funding, job security, responsibility, time, and work load. Almost all of the respondents had complaints of illness over the previous six months, however the majority of students did not take time off for those illnesses. Illness related symptoms most commonly reported were headache, sleep disturbance, flu, and allergies. Only a very small percentage had seen a physician during the previous six months and very few noted they were taking prescription medication. Over 90% rated their overall health as either average or good.

Keywords: Stress, Health, Students

Cite this paper: Michelle Calvarese, Observations of Stress and Health: A Micro Investigation of Perception among University Students, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 57-61. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20160604.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Stress can be defined in several ways, but typically includes external stressors, demand from the environment as perceived buy the individual, and physiological responses to a threatening situation [1]. Stress discourse has been predicated on the notion that stress levels can be tied to a variety of health related issues. It has been well established that childhood stress poses a greater risk for depression and anxiety in adulthood [2]. Miller et. al. has also linked childhood stress to vascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and premature mortality. It has been suggested that childhood trauma can leave epigenetic markings, leaving them more prone to inflammatory conditions in the future [3]. Over the last three decades, studies have emerged linking adult stress to cardiac disease [4-7]. DiVincenzo et. al. have demonstrated the first step of endothelia dysfunction as a result of stress that could later lead to vascular disease [6]. Furthermore, stress has been shown to exacerbate autoimmune disorders [8, 9]. Dube et. al. found that childhood stress led to an increase in hospitalizations for autoimmune disease as an adult. It is not always statistically clear however, whether stress caused the health disorder, or the health disorder induced the stress, so only correlation rather than causation can be demonstrated in most cases.High demand occupations are the focus of many stress and health related studies [10-13]. These typically examine high stress jobs such as doctors, nurses, and correctional officers. Correlations are often found between health related symptoms and stressors such as time spent at work, level of responsibilities, and risk level of job. Phipps notes unmet needs related to recognition by colleagues and a sense of personal competence may lead to diminished job satisfaction and an overall “burn-out” among physicians and nurses [12].Studies have also examined health related issues and performance or quality of life variables among university students [14-17]. Such studies typically conclude that stress levels are perceived as higher among university students compared with young adults of the same age not attending university. Canadian studies of undergraduate students found that the majority of survey respondents felt their lives were either very stressful or stressful [18, 19]. Studies conducted at a university in Sweden saw similar results [20, 21]. Furthermore, studies have linked stress among young adults with mental illness (students and non-students alike) [22, 23]. Many of these results are not much unlike those of high demand occupations, suggesting that levels of responsibility may be a common denominator between stress and health. Perceived stress and health among American university students however, is not well understood and very little research exists. Studies focused only on high-risk occupations or youth in general, obfuscates the variegated issues unique to university students. The objective of this study is to understand how stress and health are perceived among students attending a four-year university. This initiatory study could serve as baseline data for the evaluation of health education strategies that can help assist students with stress related coping mechanisms and on-campus health invention programs.

2. Methods

2.1. Demographics

- The sample population for this study consisted of students attending a four-year university in the central valley of California. The majority of students (85%) are full time students. Males comprise 42% of the student body and females comprise 58%. As a Hispanic serving institution, 46% of the student body is Hispanic. Approximately 22% are Caucasian, and 14% are Asian. The average course load for undergraduates is 13.2 units and 15% complete their educational requirements and graduate in 4 years (the majority take 6 years) [23]. Largely considered a commuter campus, many students also work full-time or part-time.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

- This study utilized a survey approved by the university Internal Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects. All participants were 18 years of age or older and currently enrolled as university students. Participants were not required to complete the survey.

2.3. Data Collection

- Instructors administered surveys at the end of General Education classes across the campus. General Education classes were chosen in order to acquire answers from a diverse group of students, rather than using courses designed for majors where students may have similar interests and backgrounds. Additionally, student assistants were used to randomly conduct surveys on campus. Completing the survey was optional and there was no incentive offered for participating in the study. The survey was completed by 226 students. Respondents answered questions via dichotomous responses, multiple-choice responses, or a rating scale. Not every student answered every question, so there is slight variability between observed frequencies for each question. The same sample group was used for each question.The survey consisted of the following questions:Ÿ How would you rate your current stress level? (rating scale)Ÿ What are the main causes of that stress? (multiple choice)Ÿ What type of illness or complaints have you experienced over the last year? (multiple choice)Ÿ Have you taken time off for that illness over the last year? (dichotomous)Ÿ How often have you visited a physician for illness during the past 6 months? (multiple choice)Ÿ How many prescription medications are you currently taking? (multiple choice)Ÿ How would you rate your overall health? (rating scale)

3. Results

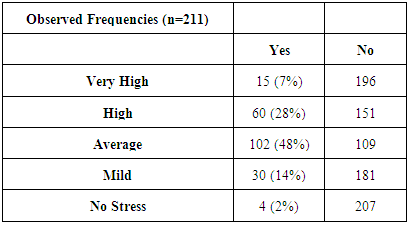

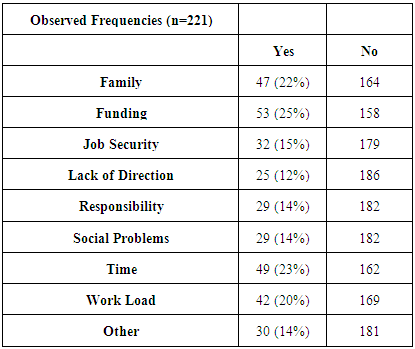

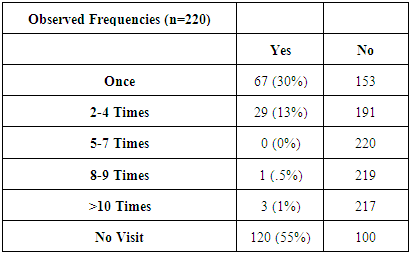

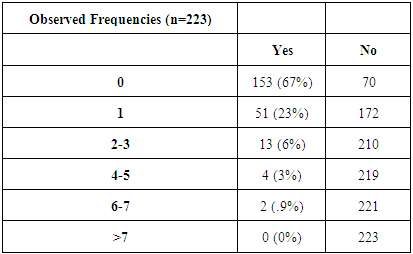

- Table 1 shows that almost half of the students that completed the survey perceived their stress level as “average.” Only 7% of respondents perceived their stress level as very high. Despite stress level being perceived as “average,” Table 2 shows there were multiple noted causes. One-quarter of the respondents cited “funding” as their main cause of stress, followed by “family,” “time,” and “workload.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

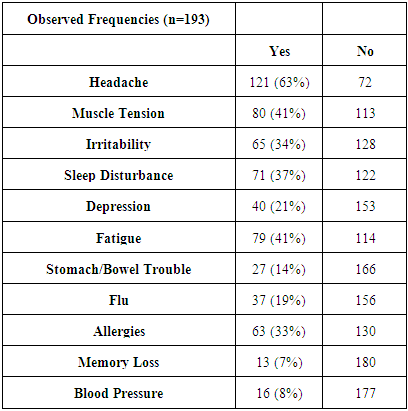

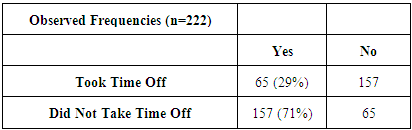

- In summation, the majority of students rated their stress as “average.” The primary causes of stress were funding, family, job security, responsibility, time, and work load. Almost of the respondents had complaints of illness. Common illness related symptoms were headache, muscle tension, irritability, sleep disturbances, fatigue, and allergies. The majority of students had not seen a physician and were not taking prescription medications. The majority of students rated their overall health as excellent, good, or average.Interestingly, stress levels were not as high as expected. It was expected that students would rate their perceived stress as “very high” or “high” considering most students work full-time or part-time in addition to attending university. Perceived high stress levels also were more commonly noted in literature. Perhaps the “average” rating is correlated to the average unit load of 13 units. Additionally, “stress” may have a negative connotation that students did not want to easily admit and/or it was not adequately defined. It was expected however, that “funding” would rate highly as a stressor. Although this particular university is a subsidized state school with relatively low tuition, the central valley of California is stricken with some of highest unemployment and poverty rates in the nation.It was not remarkable that “headache” ranked very highly among students as an experienced illness. It was also predicted that muscle tension and fatigue would rank highly. It was noteworthy however, that “allergies” did not rank higher as the area of the country in which the survey took place has particularly high pollution levels and relatively high allergy and asthma rates.The majority of students did not take off due to their illness. It was not clear however, whether this was referring to their academic responsibilities or other responsibilities. It was not unforeseen that approximately half of the students did not visit a physician during the past 6 months. Many students do not have access to affordable health care and unfortunately many do not utilize the campus health center. A very small percentage had seen a physician frequently, which most likely involved a chronic condition. This correlated with the number of medications taken, as the majority of students were not taking any medications.Almost all the students rated their overall health between “excellent” and “average” with the majority of students choosing “good.” Given the age range of the students, this was an anticipated response.

5. Future Research

- For all intents and purposes, this study served as an exploratory study. As such, much was learned on how to improve the study, beginning with the survey instrument. Given the complexity of student responsibilities, certain variables could be better defined. “Time taken off” for example, did not specify whether it was in reference to school, work, family responsibilities, etc. Secondly, now that a baseline has been established, a larger sample group should be used. This will lessen the impact of varying observed frequencies between survey questions.Future research with a larger sample group would be required to provide meaningful correlations between variables and provide insight into statistically significant links. Demographics could also be analyzed to determine if correlations differ depending upon characteristics such as income, ethnicity, or marital status. Given the propensity of university students to develop mental health impairments such as anxiety, as a result of stress, it may also be interesting to incorporate questions regarding mental health issues in a future survey.An identical survey could be then be administered to other campuses within the state university system, as well as other universities throughout the country, to see if similarities exist between the type of university (state, private, etc.). Finally, results could be compared to other groups typically used in stress and health studies such as nurses, doctors, and first responders. These results could be extremely useful for campus counselors and campus programs to improve discourse with students struggling with stress and stress related issues and legitimate the need for campus health related programs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author has no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML