-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2016; 6(3): 48-52

doi:10.5923/j.health.20160603.03

Opportunistic Intestinal Protozoal Infections among Immunosuppressed Patients in a Tertiary Hospital Makkah, Saudi Arabia

Hani S. Faidah1, Dina A. Zaghlool2, Soltane R.3, Fifi M. Elsayed4

1Microbiology Department, Faculty of Medicine Um Al-Qura University, Makah, Saudi Arabia

2Parasitology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Assuit University, Assuit, Egypt, Laboratory and Blood Bank Department, Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

3Biology Department, Faculty of Science, Um Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

4Oncology Department and Nuclear Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Dina A. Zaghlool, Parasitology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Assuit University, Assuit, Egypt, Laboratory and Blood Bank Department, Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Introduction: Intestinal parasitosis constitutes a major public health problem, especially in developing countries intestinal protozoa parasites play an important role in triggering diseases in specific groups such as immunocompromised individuals and young children. Methods: A total of 269 stool samples were collected from inpatient and outpatient clinics of Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Makah, Saudi Arabia. Two groups of patients were studied, 139 immunosuppressed patients and 130 immunocompetent patients. Stool samples were examined by wet saline and iodine mounts. A concentration technique, Mini parasep® Concentrator was carried out for negative stool samples by wet saline and iodine mounts. Samples were stained by modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain. The ImmunoCard STAT CGE rapid test was done for the diagnosis of Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardialamblia and Entamoebahistolytica. Aim of the present work: The present study determines the prevalence and symptoms associated with opportunistic intestinal protozoal infections among immunosuppressed patients in Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Makah, Saudi Arabia. Results: Total 60 cases (43.2%) were positive for parasitic infections among immunosuppressed patients, whereas 28 cases (21.5%) were positive in the control immunocompetent group. Blastocystishominis and Cryptosporidiumparvum were the most common protozoan infections in immunosuppressed patients (33.3% and 28.3%, respectively). Giardialamblia was the most common protozoan infection in the control group (53.6%). The most frequent symptoms among the immunosupressed patients were: flatulence, (39.5%); weight loss, (24.4%); abdominal pain, (15.1%); diarrhea, (9.3%). There was a significant difference between the two groups: flatulence and abdominal pain were more prevalent in the control group than in immunosupressed patients (p < 0.05).

Keywords: Opportunistic, Intestinal, Protozoa, Immunosuppression

Cite this paper: Hani S. Faidah, Dina A. Zaghlool, Soltane R., Fifi M. Elsayed, Opportunistic Intestinal Protozoal Infections among Immunosuppressed Patients in a Tertiary Hospital Makkah, Saudi Arabia, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 48-52. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20160603.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The immune response of an immunocompetent host against parasites is a complex system in which both cellular and humoral defense mechanisms intervene [1]. These mechanisms involve the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the presentation of antigens to the T cells by means of antigen-presenting cells that express class II (MHCII) molecule [2]. Activated B cells also produce and secrete IgA that impedes the adhesion of extracellular parasites [3]. Immunocompromised patients have qualitative and/or quantitative alterations in their cellular and humoral responses that impede them from acting efficiently against the infections, manifested by deterioration of their general condition. They have an increased probability of acquiring parasitic infections, generally with a high degree of severity [4, 5].Intestinal parasitosis constitutes a major public health problem, especially in developing countries, where inadequate sanitary conditions and lack of hygiene result in contamination of food and water sources, with a consequent perpetuation of parasite cycles. However, even in countries where adequate sanitation conditions and education predominate, some of these parasites play an important role in triggering diseases in specific groups such as immunocompromised individuals and young children [6]. Many types of intestinal protozoan parasites affect man, provoking a wide range of symptoms that are generally associated with the gastrointestinal tract and dependent on demographic, socio-economic, physiological and immunological factors [7]. Parasitic infections that cause self-limited diarrhea in immunocompetent patients may induce profuse diarrhea in immunocompromised individuals, generally accompanied by loss of weight, anorexia, malabsorption syndrome and in some cases fever and abdominal pain [8]. Blastocystis species [9, 10], Cryptosporidium species, Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia are the most common protozoan parasites causing diarrhea in humans [11, 12]. Among these protoozon parasites, Blastocystis species is often undiagnosed [13].

2. Subjects and Methods

- This is a cross sectional study where a total of 269 cases had been collected from inpatient and outpatient clinics of Al-Noor Specialist Hospital, Makah, Saudi Arabia. The first group composed of 139 patients who had immunocompromising underlying disorders; 38 cases (27.3%) with chronic diseases as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, 50 cases (35.9%) were receiving corticosteroids, 32 cases (23%) with renal failure and 19 cases (13.6%) with malignancies. The second group consisted of 130 patients without any evidence of immunodeficiency attending the same hospital from other outpatient clinics. Inclusion criteria are: patients of both sexes, age more than 15 years old, willing to participate in the study.Exclusion criteria are: patients less than 15 years old, Patients who took anti-parasitic treatment within a month prior to the time of data collection, known patients with inflammatory bowel syndrome.Each fecal sample was collected from a patient in a clean dry container and transported to the Parasitology section in Al Noor Specialist Hospital laboratories to be examined by different techniques used for parasitic detection. Stool specimens were examined both directly as wet saline mounts and iodine stained smears. The concentration technique was done using the Mini parasep® Concentrator to detect coccidian oocysts. The ImmunoCard STAT CGE rapid test was done for the diagnosis of Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining was performed [14] for positive cases by immune card STAT CGE Rapid Test [15].Mini parasep® Concentrator is manufactured by APACOR [16]. It is an efficient device used to concentrate larvae and protozoan cysts, and to recover coccidian oocysts such as Cryptosporidium parvum and Isospora belli in stool samples. Mini parasep® Concentrator was used according to the directions of the manufacturer. Test procedure involves introducing a pea sized faecal sample using the spoon on the end of the Mini Parasep® filter in the prefilled Mini Parasep® units and Mix thoroughly. Seal the Mini Parasep® by screwing in the filter/ sedimentation cone unit. Shake and invert Mini Parasep® and centrifuge at 1200 g for three minutes. Unscrew and discard the filter and mixing tube. Pour off all the liquid above the sediment. Add one drop of deposit onto a slide to one drop of saline or iodine solution, mix sample and cover with cover-slip. The ImmunoCard STAT CGE (Meridian Bioscience) is a rapid in vitro qualitative immunoassay that simultaneously detects and distinguishes between Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica antigens in human stool specimens. The ImmunoCard STAT CGE is based on the immunological capture of colored microparticles as the move along a membrane on which the monoclonal antibody has been immobilized. The ImmunoCard STAT CGE Immunoassay diagnostic kit was used according to the directions of the manufacturer. Test Procedure bring specimen to 20-30C. Mix stool thoroughly as possible prior to pipetting. Mix sample Diluent /negative control prior to use. Using the dropper assembly provided with the sample Diluent /negative control, add 1.0 ml of sample Diluent to a test tube. Add a small portion of approximately 5-6mm size with a swab, wooden applicator. For liquid or semi-solid stools we add 100ul of stool using a pipette. Vortex for a minimum of 15 seconds. Centrifuge for 5 minutes at 700xg. Remove the immunoCard STAT CGE test device from its foil pouch and label with the patient identification. Add 125ul of the prepared specimen to the sample port of the device. Incubate the test at 19-27°C for 10 minutes. Read the results within 1 minute of the end of incubation.Negative: Only a single purple colored band appears at the control line marked C on the device. Positive: Cryptosporidium: In addition to the purple control band, a blue band appears at position 1 on the device frame in the interpretation window. Giardia lamblia: In addition to the purple control band, a red/pink band appears at position 2 on the device frame in the interpretation window.Entamoeba histolytica: In addition to the purple control band, a green band appears at position 3 on the device frame in the interpretation window.Ethical consideration:Patients were informed about the study and were required to provide written consent for participation in the study. Patients diagnosed by stool examination as infected were treated by the doctor on duty.

3. Statistical Analysis

- Data were presented as percentages and proportions. For the categorical variables, the chi-square or Fisher exact test was used and the t-Student test was used for the continuous variables as appropriate. The significance level adopted was 0.05.

4. Results

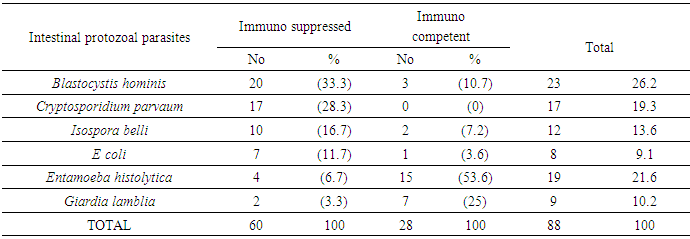

- Out of the 139 stool samples, 60(43.2%) tested samples were positive for protozoal intestinal parasites among immunosupressed group. Blastocystis hominis, 20(33.3%); Cryptosporidium, 17(28.3%); Isospora belli, 10 (16.7%), E coli 7(11.7%) Entamoeba histolytica, 4 (6.7%); Giardia lamblia, 2 (3.3%). In the second control group, out of 130 stool samples collected 28 samples (21.5%) were positive for protozoal intestinal parasites, with the following prevalence: Giardia lamblia, 15 (53.6%), Entamoeba histolytica, 7(25%), Blastocystis hominis, 3(10.7%); and Isospora belli 2(7.2%), E coli 1(3.6%) TABLE (1).The most frequent symptoms among the immunosupressed patients were: flatulence, (39.5%); weight loss, (24.4%); abdominal pain, (15.1%); diarrhea, (9.3%). The most frequent symptoms among the control patients were: flatulence, (56%) and abdominal pain, (40%). There was a significant difference between the two groups: flatulence and abdominal pain were more prevalent in the control group than in immunosupressed patients (p < 0.05).

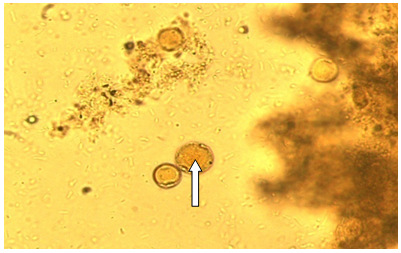

| Figure (1). Blastocystis hominis cyst-like in a wet mount; stained in iodine stain fecal smear. 40x |

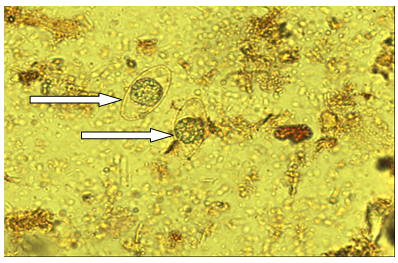

| Figure (2). Isospora belli cyst; fecal smear iodine stain 40x |

|

5. Discussion

- Intestinal parasitic infections constitute a major public health problem, especially in developing countries. However, even in countries with adequate sanitation conditions and education predominate, some of these parasites play an important role in triggering diseases in specific groups such as immunosuppressed individuals and young children [6].In the current study, 60 cases (43.2%) were positive for parasitic infections among the 139 immunosuppressed patients examined, whereas 28 cases (21.5%) were positive in the control group. And, also in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. They found intestinal parasites in 39.7% of immunosuppressed patients [17]. And also study is done in Egypt, they detected intestinal parasites in 30% among immunosuppressed Egyptian patients and 10% in healthy controls [18]. And the same result was obtained by one study in Kocaeli, Turkey that found intestinal parasites in (43.7%) of dialysis patients and (12.7%) of the control group [19].In the present study, we found that the frequency of intestinal protozoal infections among immunosuppressed patients was significantly higher than that of immunocompetent individuals. The most common protozoa found in immunosupressed patients were Blastocystis hominis, Cryptosporidium and Isospora belli. This data were in agreement with the results are reported in individuals in southwest Ethiopia. [20]. However, these opportunistic parasites were rare in immunocompetent patients. [21]. On the other hand in one study found that the prevalence of intestinal parasites in immunosuppressed patients was as same as that in immunocompetent individuals. [22]When comparing the prevalence of parasites in both groups we found that Cryptosporidium was recovered only from immunocompromised patients (p < 0.0001), this was in agreement with the finding obtained by other studies that found Cryptosporidium is the most common parasite encountered in the immunocompromised host, and such a result reinforces the theory of immunodeficiency as a determinant for Cryptosporidium infections. [12, 23]In the present study, Blastocystis was the most common infection in the immunosupressed 33.3%. This was agreement with the finding obtained by other studies that found B. hominis was the commonest parasite among patients with hematological malignancy (13%). [19, 24] This protozoan is one of the most common organisms detected in stool specimens, but there has been considerable controversy regarding whether they represent a commensal organism or a true pathogen. The mode of transmission is not fully understood; fecal-oral transmission has been postulated [25].Some author has suggested that contaminated water may also be a source of infection [26]. Blastocystis spp. has also been found in animals including monkeys, rodents and poultry. There seems to be poor host specificity; transmission occurs from human to human and between humans and animals [27].Isospora belli diarrhea can sometimes be fulminant in immunocompromised patients. It is endemic in tropical and subtropical areas. [28]. Isospora belli was detected in 16.7% of immunosupressed patients and in 7.2% of immunocomponent patients. However it is an opportunistic parasite which cause diarrhea in immunosupressed patients. The diarrhea is often associated with colicky abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, malabsorption, weight loss and peripheral eosinophilia and it is typically self limited in immunocompetent host [29].In agreement with our study, in Egypt, Minia District Isospora belli was detected in 9.1% of immunosupressed patients and in 6.3% of immunocompetent patients [30]. However, the reasons for these patterns in parasite distribution are unclear. It has been postulated that colonization of the intestinal tract by parasites might be influenced by enteropathy induced by any causes that make suppression of the immunity.In the present study, E. histolytica and G. lamblia were more prevalent in immunocompetent patients than in immunosupressed patients (53.6% vs. 6.7% and 25% vs. 3.3% respectively) and this results were agreement with one study that found the prevalence of E. histolytica and G. lamblia in immunocompetent patients than in immunosupressed Egyptian patients (24.6% vs. 6% and 17.6% vs. 4.8% respectively) and explained that infection in immunosupressed patients may be a cause of some changes in the gut structure that may not be suitable for these parasites [30].The most frequent symptoms among the immunosupressed patients were: flatulence, (39.5%); weight loss, (24.4%); abdominal pain, (15.1%); diarrhea, (9.3%). The most frequent symptoms among the control patients were: flatulence, (56%) and abdominal pain, (40%). There was a significant difference between the two groups: flatulence and abdominal pain were more prevalent in the control group than in immunosupressed patients (p < 0.05). This was in agreement with the finding obtained by one study that found the predominant symptoms in both control group and group of patients suffering from hematological malignancy were abdominal pain (87-89.5%), diarrhea (70-89.5%) and flatulence (74-68.4%) [24].However, when comparing the symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, no significant differences were detected in the prevalence of various parasites in both groups under study. Similar results were reported by other studies which confirm the need to look for other causes associated with clinical gastrointestinal manifestations. [31, 12]. Considering the symptoms and their association with parasitism, there was no association relating them to the presence of any parasites even when comparing symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in both groups [32].On the other hand, it should be emphasized that some of the patients included had cancers, and hematological alterations known to produce gastro-intestinal manifestations, which could also have been due to the treatments used. Thus it was not possible to discriminate in all cases whether symptoms were due to intestinal parasites or the conditions mentioned. The effects of currently-available treatments and procedures for handling chronic diseases on the epidemiology of infectious agents, such as Blastocystis sp., which has been ignored for many decades by health professionals, deserves consideration. We suggest that parasitological stool examinations with emphasis on Blastocystis sp. and Cryptosporidium sp. must be included in routine follow-up evaluation of immunosupressed individuals.In addition, repeated stool microscopy at monthly intervals may be done to ensure eradication of I. Belli infection among immunosupressed patients. [28]. It is necessary to establish the etiology of the diarrheal crisis, or to detect possible asymptomatic hosts, especially in immunosupressed patients, since the drugs used to treat protozoa are not always effective against blastocystosis and cryptosporidiosis [33].Preventive measures should also be made for the acquisition of parasites through the fecal-oral contamination route. This study clarified the prevalence and associated symptoms of intestinal protozoal infections among immunosupressed patients.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML