Makarim Salman Ismail 1, Badr Eldin Hassan ElAbid 1, Asaad Mohammed Ahmed Abd Allah Babker 2

1Department of Clinical Chemistry, College of Medical Laboratory Science, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Khartoum, Sudan

2Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Al-Ghad International College for Health Sciences, Al-Madinah Almonawarah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Asaad Mohammed Ahmed Abd Allah Babker , Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Al-Ghad International College for Health Sciences, Al-Madinah Almonawarah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The objective of this study is to evaluate the influence of effect of cigarette smoking on serum alpha-1-antitrypsin, serum and salivary calcium levels in Sudanese cigarette smokers. Material and Method: The study is a prospective analytical case control study was conducted in University of Medical Sciences and Technology (Sudan). A total of 100 male smokers and non-smokers were recruited for this study. After consent was obtained by all volunteers and structural questioner used to collect data. Subsequently five ml of venous blood was obtained for measuring serum alpha-1-antitrypsin and serum calcium. Two ml of unstimulated whole saliva was collected for the estimation of salivary calcium. Result: Salivary and serum calcium levels were significantly high and a significantly decrease in the levels of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin in cigarette smokers compared to the control (P<0.05). Mean ± SD for controls versus cigarette smokers: (3.56 ± 1.07) versus (11.54 ± 2.26) mg/dl, for salivary calcium. (9.02 ± 0.50) versus (10.61 ± 0.97) mg/dl, for serum calcium. (3.20 ± 0.52) versus (2.46 ± 0.76) g/l, for serum α-1-antitrypsin. Conclusions: In conclusion, cigarette smoking reduces the levels of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin and there is a negative correlation with both; the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the duration of smoking in years. Moreover, cigarette smoking increases the levels of serum and salivary calcium and there is a positive correlation with both; the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the duration of smoking in years.

Keywords:

Sudanese cigarette Smoking, Serum Alpha 1-Antitrypsin, Serum and Salivary Calcium

Cite this paper: Makarim Salman Ismail , Badr Eldin Hassan ElAbid , Asaad Mohammed Ahmed Abd Allah Babker , Quantitative Assessment of Serum Alpha-1-Antitrypsin, Serum and Salivary Calcium Levels among Sudanese Cigarette Smokers, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 17-21. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20160602.01.

1. Introduction

Tobacco is the only legal drug that kills many of its users when used exactly as intended by manufacturers. WHO has estimated that tobacco use (smoking and smokeless) is currently responsible for the death of about six million people across the world each year with many of these deaths occurring prematurely [1]. Two general classes of cigarette smoke exist. Mainstream smoke (MS) is the puff of smoke inhaled by active smokers, while sidestream (SS) smoke burns off the end of cigarettes and is inhaled by passive smokers. SS smoke, which is the major component of environmental tobacco smoke, is also referred to as secondhand smoke [2]. Saliva, the fluid in the mouth, is a combined secretion of the three pairs of salivary glands the parotid, the submandibular and the sublingual; together with numerous small glands. The smoke of tobacco during smoking is spread to all parts of the oral cavity and therefore, the taste receptors, a primary receptor site for salivary secretion, are constantly exposed [3]. Smokers show increased levels of circulating leukocyte counts and inflammatory markers, including CRP, intercellular adhesion molecule Type-1, interleukin (IL-6), E-selectin, and P-selectin [4]. Alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT) is formed in the liver, and it participates in protecting the lungs from neutrophil elastase, a particular enzyme that is capable of disrupting connective tissue [5]. Evidence has shown that cigarette smoke can lead to oxidation of methionine 358 of α1-antitrypsin (382 in the pre-processed form containing the 24 amino acid signal peptide), a residue essential for binding elastase; this is thought to be one of the primary mechanisms by which cigarette smoking (or second-hand smoke) can lead to emphysema [6]. In smokers, the levels of alpha -1-antitrypsin were exclusively and considerably raised and were related to the extent of smoking [7]. Calcium is the major component of bones and teeth, and it is not surprising that disturbances in calcium metabolism have been implicated in most of the major chronic diseases, including osteoporosis, kidney disease, obesity, heart disease, and hypertension [8]. Smokers who exhibited greater plaque and calculus formation had also shown elevated calcium concentration and elevated calcium phosphate ratio in plaque [9]. The objective of this study is to evaluate the influence of effect of cigarette smoking on serum alpha-1-antitrypsin, serum and salivary calcium levels in Sudanese cigarette smokers.

2. Material and Method

The study is a prospective analytical case control study. The subjects of the study were selected from the students and teaching staff of University of Medical Sciences and Technology (Sudan). A total of 100 subjects Sample were randomly selected (with N - 1) for observation and confidence intervals were generated for each calculated value and divided into two groups; smokers (50%) and non-smokers (50%) as controls, the age range of all subjects was (17-63) years. After consent was obtained by volunteers clinical and demographics data were obtained by structural questionnaire about (present and past history of diseases, number of cigarettes smoking per day and smoking history). Five ml of venous blood and two ml of saliva were collected from each volunteer. A colorimetric assay was performed to detect AAT serum levels. This was done by using Roche automated clinical chemistry analyzer (Hitachi 912); it has commercial kits containing reagents, calibrator; C.f.a.s protein (Cat No. 11355279); and controls from Roche Company (Germany). The concentration of in vivo calcium (blood and saliva) measured by colorimetric assay using an automated clinical chemistry analyzer from Roche having a kit with reagents, calibrator; C.f.a.s (Cat.No.10759350); and controls. The data collected in this study were analyzed by using SPSS computer analysis program. To test for inter-observer variations; the readings of the observers were compared using dependent t-test. A linear regression analysis was used to test for the correlation between the number of cigarettes smoked per day and duration of smoking; and the levels of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin, calcium and salivary calcium levels. P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The cut-off values were based on the following laboratory reference values: Serum Alpha-1-Antitrypsin values less than 1.5 g/L were considered low and values greater than or equal to 1.5 g/L were considered normal. Serum calcium of values less than 8.5 mg/dl were considered low and values greater than or equal to 8.5 mg/dl were considered normal. Saliva calcium of values less than 4 mg/dl were considered low and values greater than or equal to 6 mg/dl were considered normal.

3. Result

Table 1. Comparison of the means of serum AAT between cigarette smokers and non-smokers: Shows significant difference between the means of serum AAT in the control group (n=50) and the test group (n=50). (Mean ± SD): (3.20 ± 0.52) versus (2.46 ± 0.76) g/l, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

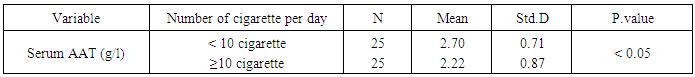

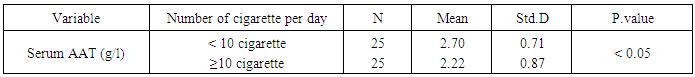

Table 2. The relationship between the numbers of cigarette smoked per day and the levels of serum AAT: shows significant difference between the means of the serum AAT in smokers who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day compared to those smoked < 10 cigarettes per day. The mean ± SD of serum AAT was (2.70 ± 0.71) g/l in subjects smoking < 10 cigarettes per day, and was in those who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day (2.22 ± 0.87) g/l, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

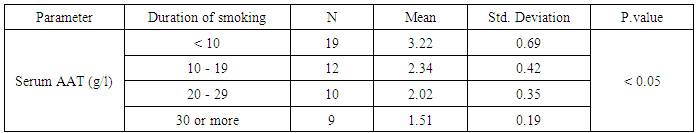

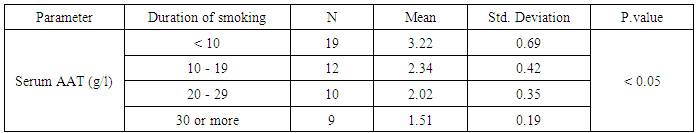

Table 3. The relationship between the duration of smoking and the levels of serum AAT: Shows significant difference between the means of serum AAT in smokers according to the increase in the duration of smoking in years. The mean ± SD of serum AAT in groups of duration in years {(<10), (10 - 19), (20 - 29) and (30 or more)} were {(3.22 ± 0.69), (2.34 ± 0.42), (2.02 ± 0.35) and (1.51 ± 0.19) g/l} respectively, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

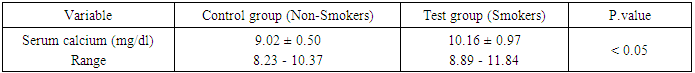

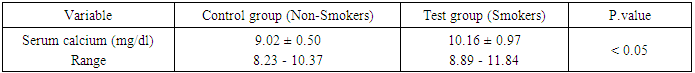

Serum CalciumTable 4. Comparison of the means of serum calcium between cigarette smokers and non-smokers: shows significant difference between the means of serum calcium in the control group and the test group. (Mean ± SD): (9.02 ± 0.50) versus (10.61 ± 0.97) mg/dl, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

Table 5. The relationship between the numbers of cigarette smoked per day and the levels of serum calcium: shows significant difference between the means of the serum calcium in smokers who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day compared to those smoked < 10 cigarettes per day. The mean ±SD of serum calcium was found to be (10.57 ± 1.09) mg/dl in subjects smoking < 10 cigarettes per day, and was in those who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day (10.67 ± 0.87) mg/dl, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

Table 6. The relationship between the duration of smoking and the levels of serum calcium: shows significant difference between the means of serum calcium in smokers according to the increase in the duration of smoking in years. The mean ± SD of serum calcium in groups of duration in years {(<10), (10 - 19), (20 - 29) and (30 or more)} were {(9.85 ± 0.85), (10.84 ± 0.79), (10.80 ± 0.57) and (11.71 ± 0.12) mg/dl} respectively, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

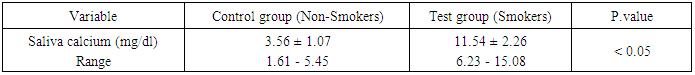

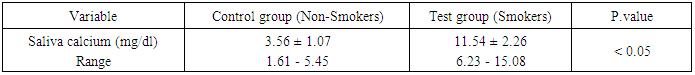

Salivary CalciumTable 7. Comparison of the means of salivary calcium between cigarette smokers and non-smokers: shows significant difference between the means of salivary calcium in the control group and the test group. (Mean ± SD): (3.56 ± 1.07) versus (11.54 ± 2.26) mg/dl, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

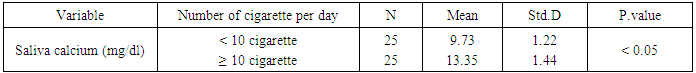

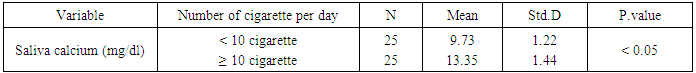

Table 8. The relationship between the numbers of cigarette smoked per day and the levels of salivary calcium: shows significant difference between the means of the salivary calcium in smokers who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day compared to those smoked <10 cigarettes per day. The mean ± SD of salivary calcium in subjects smoking < 10 cigarettes per day was (9.73 ± 1.22) mg/dl, where it was in those who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day (13.35 ± 1.44) mg/dl. These results show significant increase in salivary calcium level (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

Table 9. The relationship between the duration of smoking and the levels of salivary calcium: shows significant difference between the means of salivary calcium in smokers according to the increase in the duration of smoking in years. The mean ± SD of salivary calcium in groups of duration in years {(9.75 ± 1.38), (11.78 ± 1.19), (12.55 ± 1.92) and (14.27 ± 1.35) mg/dl} respectively, (P<0.05)

|

| |

|

4. Discussion

Cigarette smoking remains harmful habit that facilitates the development and progression of periodontal diseases, even when other contributory factors, such as oral hygiene, plaque. Several studies were conducted to evaluate the hazards of cigarette smoking were well recognized worldwide [10-12]. Several studies were conducted in Sudan about the risk of smoking on human health, but there are no studies conducted in Sudan in open literature, to our knowledge about the influence of cigarette smoking on serum alpha-1-antitrypsin, and salivary calcium levels. The objective of this study was to assess the role of smoking on alteration of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin, serum and salivary calcium levels among Sudanese smokers. We investigate calcium saliva among cigarette smoker because salivary calcium may be important with regard to both dental and gingival health by way of effect on mineralization of plaque [13]. Our result showed there was a significant increase in the levels of salivary calcium among cigarette smokers when compared to the control (P<0.05), (3.56 ± 1.07) versus (11.54 ± 2.26) mg/dl, for salivary calcium. These findings are consistent with several previous reports demonstrated appositive correlations between high salivary calcium content and chronic cigarette smoking [14, 15]. Another pilot result conducted by Kiss E et al (2010), aimed to assess the possibility of differences in the calcium concentration of the saliva between smoker and non-smoker patients and concluded that higher salivary calcium levels than those in nonsmokers. Also our result disagreed with Ghulam et al. found that long-term smoking does not adversely affect the taste receptors response and hence salivary flow rate [16]. Our result also found there was a significant increase in the levels of serum calcium among cigarette smokers when compared to the control (9.02 ± 0.50) versus (10.61 ± 0.97) mg/dl. Increase in serum calcium levels among chronic cigarette smokers are correlated with increase in plasma lipid especially LDL cholesterol. HDL may be involved in the modulation of calcium channels and its decrease might have increased the concentrations of calcium in the plasma of chronic cigarette smokers [17]. There were many studies found the same relation between serum calcium level and smoking of our result [18, 19]. Also our result found there was a significant decrease in the levels of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin among smokers when compared to the control (3.20 ± 0.52) versus (2.46 ± 0.76) g/l. This finding assist by that direct exposure of alpha-1-antitrypsin to gas phase cause loss of elastase inhibitory capacity leading to formation of reactive free radicals from smoke that inactivate alpha-1-antitrypsin by oxidizing methionine 358 terminal amino acid [20]. Our result in agree with study conducted by A K Sayyed, et al (2008) concluded that enhanced oxidative stress and reduced alpha-1-antitrypsin in cigarette smokers [21]. Also our finding disagree with another study conducted by FouadH, et al, (2013) among Malaysian smokers and concluded that alpha-1-antirypsin levels were higher among those smokers [5]. Our study also estimate the duration of smoking and numbers of cigarette per day and found there is a negative correlation with both; the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the duration of smoking in years with alpha-1- antitrypsin levels. This finding disagree with some reported that increase in number of cigarettes per day make smokers more susceptible to enhanced oxidative stress along with decline in α1-antitrypsin [21]. Our study found cigarette smoking increases the levels of serum and salivary calcium and there is a positive correlation with both; the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the duration of smoking in years. This may be agree with that long term use of tobacco decrease the sensitivity of taste receptors which in turn leads to depressed salivary reflex [3]. Our study has some limitations, such as the relatively small number of subjects (case and control).Our finding on these result must be determined in further large scale controlled studies.

5. Conclusions

Concluded that cigarette smoking reduces the levels of serum alpha -1- antitrypsin and there is a negative correlation with both; the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the duration of smoking in years. Moreover, cigarette smoking increases the levels of serum and salivary calcium and there is a positive correlation with both; the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the duration of smoking in years.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express gratitude to the University of Medical Sciences and Technology (Sudan).Also we are grateful thank all the volunteers who agreed to participate in this study.

References

| [1] | World Health Organization (WHO), 2015. Global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization. |

| [2] | USDHHS (2006) .The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the surgeon general. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Offices on Smoking and Human Health, Atlanta. |

| [3] | Khan, Ghulam Jillani, Muhammad Javed, and Muhammad Ishaq. "Effect of smoking on salivary flow rate." Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences 8.2 (2010). |

| [4] | T. S. Perlstein and R. T. Lee, “Smoking, metalloproteinases, and vascular disease,” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 250–256, 2006. |

| [5] | Fouad H. Al-Bayaty, NorAdinar Baharuddin, Mahmood A. Abdulla, Hapipah Mohd Ali, Magaji B. Arkilla, and Mustafa F. ALBayaty, “The Influence of Cigarette Smoking on Gingival Bleeding and Serum Concentrations of Haptoglobin and Alpha 1-Antitrypsin,” BioMed Research International, vol. 2013, Article ID 684154, 6 pages, 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/684154. |

| [6] | Taggart, C., Cervantes-Laurean, D., Kim, G., McElvaney, N. G., Wehr, N., Moss, J., & Levine, R. L. (2000). Oxidation of either Methionine 351 or Methionine 358 in α1-Antitrypsin Causes Loss of Anti-neutrophil Elastase Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275(35), 27258–27265.doi:10.1074/jbc.M004850200. |

| [7] | G. T. Wolf, P. B. Chretien, and J. F. Weiss, “Effects of smoking and age on serum levels of immune reactive proteins,” Otolaryngology, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 319–326, 1982. |

| [8] | Tordoff MG. Calcium: Taste, Intake, and Appetite. Physiol Rev 2001; 81: 1567-97. |

| [9] | Mac Gregor DM, Edgar WM. Calcium and phosphate concentrations and precipitate formation in whole saliva in smokers and non smokers. J Periodontol Res. 1986; 21: 429–33. |

| [10] | Fagerström K. The epidemiology of smoking: health consequences and benefits of cessation. Drugs. 2002; 62 Suppl 2:1-9. 2. |

| [11] | Been JV, Nurmatov UB, Cox B, et al. Effect of smoke-free legislation on perinatal and child health: A systematic review. The Lancet 2014. doi:10.1016/S01406736(14)60082-9. |

| [12] | Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Regional, disease specific patterns of smoking-attributable mortality in 2000. Tob Control. 2004 Dec; 13(4):388-9. |

| [13] | Kaufman E, Lamster IB, Analysis of saliva – A review J Clin Periodontol 2000 27:453-65. |

| [14] | Macgregor IDM, Edgar WM. Calcium and phosphate concentrations and precipitate formation in whole saliva from smokers and non-smokers. J Periodontal Res. 1986; 21: 429–33. |

| [15] | Varghese, Megha, et al. "Quantitative Assessment of Calcium Profile in Whole Saliva From Smokers and Non-Smokers with Chronic Generalized Periodontitis." Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR 9.5 (2015): ZC54. |

| [16] | Rad, Maryam, et al. "Effect of long-term smoking on whole-mouth salivary flow rate and oral health." Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects 4.4 (2011): 110-114. |

| [17] | Lind, L., Jakobsson, S., Lithell, H., Wengle, B. and Ljunghall, S. (1988) Relation of serum calcium concentration to metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Br. Med. J., 15, 960–963. |

| [18] | Brot C, Jorgensen NR and Sorensen OH, The influence of smoking on vitamin D status and calcium metabolism, Eur J Clin Nutr, 53, 920-926 (1999). |

| [19] | Breitling, Lutz P. "Smoking as an Effect Modifier of the Association of Calcium Intake With Bone Mineral Density." The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 100.2 (2014): 626-635. |

| [20] | Somayajulu, Rao R, Reddy. Serum Alpha 1-Antitrypsin in smokers and non-smokers. Ind J Clin Biochem 1996; 11(1): 70-72. |

| [21] | Sayyed, A. K., et al. "Oxidative stress and serum α1-Antitrypsin in smokers." Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 23.4 (2008): 375-377. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML