-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2016; 6(1): 7-11

doi:10.5923/j.health.20160601.02

Career Decision Making and Intent to Take Credentialing Exam: Perspectives of Dietetic Technician Students

Kathleen Border1, Arthur M. Michalek2, Lisa Rafalson3, Ryan Hartnett4

1Dietetics Department, D’Youville College, Buffalo, NY, USA

2Department of Epidemiology and Environmental Health and Director, Division of Health Service Policy & Practice, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA

3Health Services Administration Department, D’Youville College, Buffalo, NY, USA

4Academic Affairs, Assistant Vice-President, Villa Maria College, Buffalo, NY, USA

Correspondence to: Kathleen Border, Dietetics Department, D’Youville College, Buffalo, NY, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study examined differences in demographics and career perceptions between students who indicated their intent to take the Registration Examination for Dietetic Technicians (DTR exam) and those who did not intend to take the exam. A cross-sectional study surveyed first- and second-year students in six associate degree dietetic programs in New York State (n = 284) utilizing a paper and pencil self-administered questionnaire. The majority of students were White (79.8%), female (72.6%), and had no previous college degree (74.7%), with an average age of 25.87 ± 7.98 years. Students in their second year of study and with health-based career interest were more likely than first year students to indicate intent to take the DTR exam (ρ ≤ .05). The majority of respondents (90%) indicated their intent to take the DTR exam, which differs from national data that reports 61% of eligible students take the DTR exam. Education programs should identify methods to encourage eligible students to take the DTR exam and become a credentialed practitioner. Further research should examine the gap of student intent and test taking in this population to maximize the number of credentialed dietetic technicians. A more complete understanding of the educational goals and career perceptions of the associate prepared dietetics student may further identify the validity of the associate degree as an entry point into the profession of dietetics by informing stakeholders on program design, program recruitment, and student career advisement.

Keywords: Dietetic Technician, Registered, Registration Examination for Dietetic Technicians, Career Decisions

Cite this paper: Kathleen Border, Arthur M. Michalek, Lisa Rafalson, Ryan Hartnett, Career Decision Making and Intent to Take Credentialing Exam: Perspectives of Dietetic Technician Students, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 7-11. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20160601.02.

1. Introduction

- The Dietetic Technician, Registered (DTR) is a food and nutrition practitioner who plays an important role in health care by delivering safe, culturally competent, quality food and nutrition services to a variety of audiences. The DTR has completed at least a 2-year associate degree in dietetics in a United States regionally accredited university or college, and at least 450 hours of supervised practice accredited by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND), or a bachelor's degree at a United States regionally accredited university or college and required coursework from an ACEND accredited program in dietetics. In addition, DTRs have successfully written a national DTR examination administered by the Commission for Dietetics Registration (CDR) and must complete continuing professional educational requirements to maintain registration. The role of the dietetic technician grew out of demand for an assistant level of practice during World War II and, over time, developed into a credentialed practitioner in dietetics with a defined scope of practice. [1] Limited research exists which identifies career goals of the dietetic technician student; however, dietetic students in baccalaureate programs have reported career motivators such as interest in nutrition, [2] to find work they enjoy, [3] and, desire to help others. [4] Hughes found that a long-term primary interest in nutrition, health, and helping people were the most common motivators to a career in dietetics. [5] Since the introduction of the dietetic technician, the profession has been challenged in identifying appropriate levels of practice. [6, 7] However, the American Dietetic Association’s 2008 Needs Assessment observed that 59% of DTRs were currently working in dietetics. [8] The Workforce Demand Study, published by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, reported that the requirement for the DTR credential by employers fell from 56% to 52% from 2002 to 2011. [9] Requirements by employers and regulatory agencies for credentialing are near 100% for Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs), though only two- thirds of acute and long-term care facilities require the DTR credential. Since 2004, the DTR credential has twice been threatened with elimination, [10, 11] but is still supported by the Academy and its organizational units as long as the credential remains financially viable and relevant in the practice environment. [12] In 2015 ACEND released recommendations for future education in nutrition and dietetics proposing the DTR complete a baccalaureate degree in dietetics to gain eligibility to write the DTR exam. [13] This proposed education program model is currently under review by the Academy and its organizational units. There is a gap in published literature exploring factors that influence career decisions of students enrolled in associate degree programs in dietetics. Stakeholders, including educators, the Academy, and its organizational units, employers, and college administrators need to have a better understanding of the student who decides to use an associate degree as an entry point into the career of dietetics. A more complete understanding of the educational goals and career perceptions of the associate prepared dietetics student may further identify the validity of the associate degree as an entry point into the profession of dietetics by informing stakeholders on program design, program recruitment, and student career advisement.

2. Methods

- The data for this cross-sectional descriptive study were collected from first- and second-year students enrolled in ACEND accredited associate degree programs in New York State (N = 284). Purposive sampling was employed to reach a homogeneous group of students who were similar only in their choice of being in a dietetic education program. Programs in New York State represent urban, suburban, and rural settings. A sample of n=164 students provided a 90% chance of detecting difference ≥ 1.5 standard deviations between the two populations’ means with 95% confidence. To maximize response rates, a decision was made to administer a pencil and paper survey, rather than an electronic survey. [14, 15] Surveys were mailed in bulk to program directors in October, 2014 at each of the six programs in New York State. The program director and/or designated faculty member distributed the surveys to their students and returned them via postage paid envelopes directly to the researcher. Weekly reminders (n=3) were sent electronically to program directors to maximize participation. Program directors received a $50 gift card as an incentive to distribute the surveys to their students and to return the completed surveys to the researcher. The protocol was approved by D’Youville College’s Institutional Review Board. Permission was obtained from each participating dietetic program director to recruit participants for this voluntary and anonymous study and to oversee group administration of the study surveys. The questionnaire was based on a previously developed instrument which identified values, expectations, influences, and motivations for dietetics as a career for students enrolled in baccalaureate programs in dietetics in Canada. [16] Questions related to desired job setting and perceived value of the DTR credential were added. [17] The revised survey was pilot tested for understanding and relevance by both dietetic students and registered dietitians who were not participating in the research. Completed surveys were kept secure according to institution protocol.Data were analysed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows (version 22.0, 2013). Descriptive statistics were reported. T-tests were used to compare means between two groups. Chi-square was conducted to test differences in proportions. Categories were combined judiciously to increase frequencies in cells when cell counts were less than five. The Fisher exact probability test for contingency tables was reported when two independent samples were small. Values were considered statistically significant at the ρ ≤ 0.05. All tests were two-sided. Variables measuring education history were combined into two groups; college degree (Associate, Baccalaureate, and Master’s Degree) and no college degree (high school, trade school and some college). Variables measuring when career decision was made were combined into two groups; before or after college (elementary, middle and high school, after working in the field and career changers) and during college. Variables measuring initial source of career information were combined into two groups; people (teacher, family member, guidance counsellor, RD/DTR) and other (media, college catalog, work experience). Variables measuring career interest were combined into two categories; health and nutrition related (health, food, nutrition, science, cooking) and personal interest (desire to help others, personal experience, compliments a previous degree and other). Variables measuring preferred job settings were combined into two groups; clinical and food service (college/university foodservice, enteral feeding labs in health care, foodservice equipment sales, formula rooms in health care, school foodservice, hospitals, long-term care) and community/other (child and adult care food programs, child care centers, congregate feeding programs for the older adult, Cooperative Extension programs, food banks, Head Start programs non-profit organizations, government organizations, Special Supplemental Nutrition Programs for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs ( SNAP).

3. Results

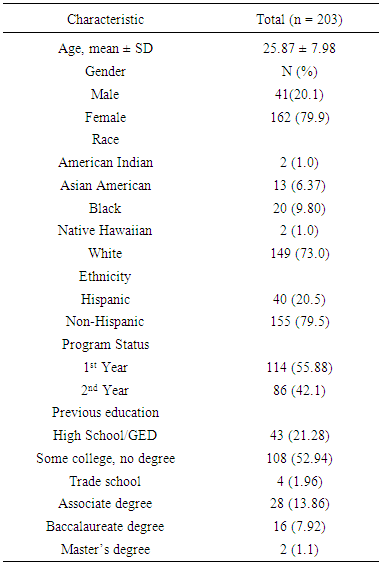

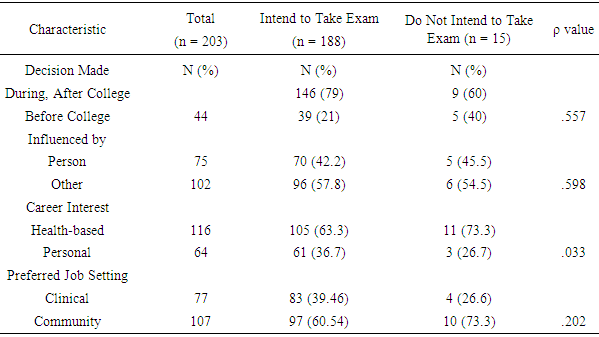

- Survey responses were received from each of the six participating programs in New York State yielding a 100% program response rate. Of the n=284 surveys distributed, n=204 were returned yielding a 72% response rate. One survey was categorized as an outlier as the respondent had a doctoral degree and this survey was eliminated from analysis. The analytic sample consisted of n=203: thirty-seven surveys had some missing data and therefore were excluded from data analysis on those questions. Overall, the respondents were female (79.9%), mean age of 25.87 ± 7.98, white (73%), and indicated they were in their first year (55.9%) of study. Characteristics of the sample population are presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

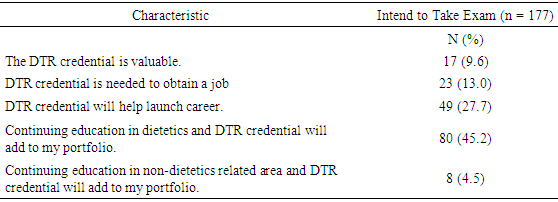

- In this sample of students (n=203) enrolled in six dietetic technician education programs in New York State, we found the majority of the respondents were female (79.9%), mean age of 25.87 ± 7.98, white (73%), and indicated they were in their first year (55.9%) of study.Factors identified as influencing career decisions of dietetic students enrolled in associate degree programs in New York State corroborated results of research on students enrolled in baccalaureate programs in Canada. Lordly had identified the two leading factors motivating students to enter dietetic education programs were an interest in nutrition (91%) and health (90%), and decisions to study dietetics while they were enrolled in college. [16] Lordly also identified the influence of family members as an early influence on students’ entrance into the study of dietetics. [17] Results of this current study demonstrated that students intending to take the DTR exam entered into dietetic programs due to an interest in health (63.3%), they were influenced by media and college materials (57.8%), and they made their career decision while they were in college (49.2%). A small percentage of students indicated their desire to work in private practice or nutrition counselling settings (data not shown) which was not listed as a choice on the survey and may not necessarily comply with the DTR’s defined scope of practice. [18] Stein found using the dietetics career development guide to chart a course for reaching higher levels of practice. [19] It is important for students to be guided to comprehend their skill sets within the DTR’s defined scope of practice. Gates and Amaya report that practitioners who wish to change practice roles should participate in careful self-evaluation, consider input from others, follow evidence-based practice guidelines, maintain ethical practices, or obtain additional certification will help DTRs determine how successful they are in maintaining competence. [20]Dietetic education programs undergo a rigorous accreditation process to verify student eligibility to take the DTR exam upon graduation. [21] Yet nationally the CDR reported only 61% of eligible students wrote the DTR exam in 2012. [22] New York State data shows that an average of 50% of eligible students took the DTR exam from 2004-2014 (C. Reidy, email communication, March 2015). This study suggests that students’ reported intent to take the DTR exam (92%) differs substantially from test taking behavior, signalling a disparity between student intent and action to become a credentialed dietetics practitioner. Bode also recognized this gap in her research on factors predicting success on the DTR exam and recommended future research should attempt to determine what factors prevent eligible candidates from taking the DTR exam. [23] Low numbers of credentialed practitioners and lack of evidenced-based care outcomes by DTRs prevent widespread adoption of requirements for the credential to obtain employment. [24] Future models of dietetics education maintain the DTR credential, yet propose the minimum of a baccalaureate degree in dietetics to write the registration examination for DTRs. Further research should examine factors influencing market demand for the DTR credential in the workplace. This study sample represented only dietetic students enrolled in associate degree programs which have undergone the ACEND accreditation process in New York State. Therefore, the current research cannot be generalized to all dietetic technician students. Strengths of this research study include the 100% program response rate and 72% student response rate. Moreover, no other study has examined associate degree programs in dietetics and career decision-making. Use of a validated survey allowed for comparisons between populations, though a limitation in this study includes the survey was adapted from one that examined Canadian dietetic baccalaureate programs.

5. Conclusions

- The DTR is trained in food and nutrition services to be an integral part of the healthcare and foodservice management team. Students with career interests based in health and nutrition as well as students in the second year of their program were more likely to report intent to take the DTR exam. This study reported that student intent to take the DTR exam was higher than the national average. A focus for future research is an investigation of more detail into DTR exam-eligible students and barriers that exist in taking the DTR exam. This will be important to consider as ACEND reviews future models of education requiring a baccalaureate degree in dietetics to write the DTR exam.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We wish to acknowledge the Health Services Administration Department for providing incentives to participating program directors. We also wish to thank the dietetic technician programs, directors, faculty and students who participated in this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML