-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2015; 5(2): 42-46

doi:10.5923/j.health.20150502.03

Development of Emotional Intelligence through Stress Experiences: The Role of Dichotomous Thinking

Hikari Namatame1, Hiroko Ueda1, Yoko Sawamiya2

1College of Psychology, School of Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

2Faculty of Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

Correspondence to: Hikari Namatame, College of Psychology, School of Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of dichotomous thinking in the development of emotional intelligence brought about by stressful experiences. A hypothetical model was investigated, whereby dichotomous thinking and cognitive appraisals entail coping style, and this coping style subsequently influences the development of emotional intelligence. A university entrance examination was used as the stress-inducing stimuli. Participants were 330 university students. Data were analyzed using multiple regression analysis. Preference for dichotomy was found to have a significant positive effect on challenge-based cognitive appraisal, and a significant negative effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal. In contrast, dichotomous beliefs had a significant negative effect on avoidance-based appraisal, and a solitary approach coping strategy. These findings suggest that holding a “preference for dichotomy” is adaptive, whereas “dichotomous beliefs” are maladaptive. Furthermore, they clarify the importance of individual characteristics when understanding the emergence of coping strategies and development of emotional intelligence, highlighting the need to consider these characteristics when developing support in an applied setting.

Keywords: Dichotomous thinking, Cognitive appraisal, Stress coping, Emotional intelligence, University entrance examination

Cite this paper: Hikari Namatame, Hiroko Ueda, Yoko Sawamiya, Development of Emotional Intelligence through Stress Experiences: The Role of Dichotomous Thinking, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 42-46. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20150502.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the important abilities that affect an individual’s social life is emotional intelligence (EI). Salovey & Mayer [1] defined emotional intelligence as “the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions.” EI has been a subject of interest in both academic and applied settings, with a growing number of studies attempting to further our understanding of a concept that has been correlated with life satisfaction, work performance, and social relationships [2].EI is not merely an innate set of abilities [3, 4]; research has shown how experiences of handling one’s emotions successfully can enhance emotional intelligence [5]. For instance, in university entrance examinations [6] and term examination periods [8], the experience of handling one’s emotions properly has been shown to enhance EI. These studies suggest that EI can develop during stressful experiences; however, the specific characteristics that may promote the development of EI during these experiences have not been investigated. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the relationship between stress experiences and the development of emotional intelligence, with specific focus on individual characteristics.Individual characteristicsDichotomous thinking refers to the propensity to think of things in terms of binary opposition: “black or white,” “good or bad,” or “all or nothing” [9]. Research has demonstrated a relationship between dichotomous thinking and maladaptive thoughts or behaviors. This form of thinking has been linked with suicide attempts [10], personality disorders [11], and eating disorders [12]. In light of this evidence, it may be suggested that those who tend to avoid dichotomous thinking are more likely to utilize an adaptive stress coping style, one that promotes the development of EI. Conversely, a strong tendency toward dichotomous thinking is likely to contribute to maladaptive stress coping styles, and would not promote the development of EI.Cognitive appraisal and stress copingLazarus & Folkman [13] noted that cognitive appraisal and stress coping should be handled separately; therefore, they will be treated as separate concepts in the present study. For cognitive appraisal, two core types were adopted for use: “avoidance,” which refers to attempting to avoid a stressful situation, and “challenge,” referring to approaching a stressful situation with an appraisal-based strategy motivated by positive emotion [13]. For stress coping, we adopted categories representing solitary and socials strategies, whereby coping is done either by oneself or with other people [14].University entrance examinationThere are two aspects central to EI: the self-domain, where one monitors, comprehends, and adapts one’s own emotional responses and behaviors, and the other-domain, where one understands and controls others’ emotions and behavior [5]. Therefore, a university entrance examination, where both of these domains are tested, may be considered a suitable training situation to develop emotional intelligence. For example, Nozaki [8] demonstrated how adaptive stress coping could lead to the development of EI during university entrance examinations.Aim The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of dichotomous thinking in the development of EI during a stressful experience. Our investigation focused on the testing of a hypothetical model, whereby dichotomous thinking and cognitive appraisals entail coping style, the adoption of which subsequently affects the development of EI. The university entrance examination was used as the stress-inducing experience.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- A total of 330 Japanese undergraduates (158 males and 172 females) participated in the study. Their average age was 19.85 years (SD = 1.36). The current study was approved by the ethical review board of the University of Tsukuba. The participants were explained in person that the participation in this study was voluntary and that there was no disadvantage if they decided not to participate. The paper was also provided to explain the voluntary participation.

2.2. Measures

- 1. Dichotomous thinkingThe Dichotomous Thinking Inventory (DTI) [9] is a 15-item self-report measure designed to assess dichotomous thinking. The DTI comprises three subscales: preference for dichotomy, dichotomous beliefs, and profit-and-loss thinking. All items are assessed on a 6-point Likert scale.2. Cognitive appraisalA 6-item, self-report measure designed to assess cognitive appraisal toward university entrance examinations [6] was used. The measure comprises two subscales: challenge and avoidance. All items are assessed on a 6-point Likert scale.3. Stress copingA 16-item, self-report scale designed to assess stress coping [6] was used. The scale, which is in Japanese, was originally developed. The measure comprises three subscales: solitary approach coping, solitary avoidance coping, and social coping. All items are assessed on a 6-point Likert scale. Nozaki & Koyasu [6] reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.87 for solitary approach coping, 0.80 for solitary avoidance coping, and 0.94 for social coping.4. Development of EIA 16-item scale, designed to assess the development of stress coping [6], was used to measure the development of EI. The item were largely from Japanese Version of Emotional Skills & Competence Questionnaire for junior high school students [7]; some of the items were changed to be appropriately fit for university students, as the original scale is targeted for junior high school students. All items are self-report and assessed on a 6-point Likert scale. Nozaki & Koyasu [6] reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.96.

2.3. Analysis

- Data were analyzed with SPSS 22 and Amos 22.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

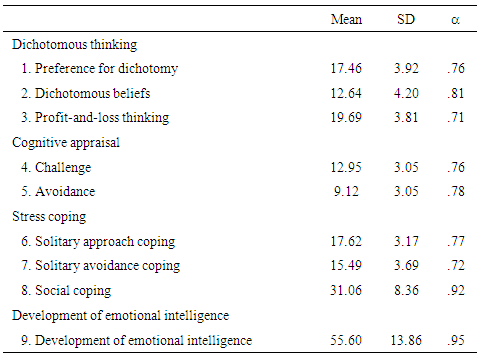

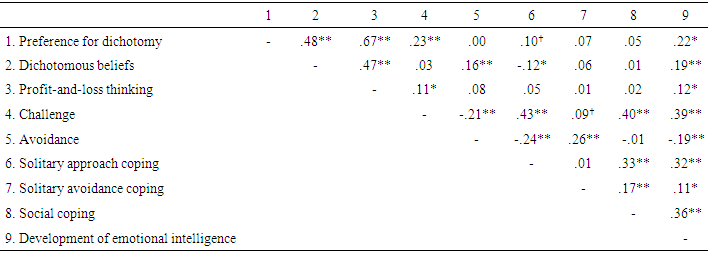

- Means, standard deviations, Cronbach's alpha coefficients, and correlations among study variables are reported in Tables 1 and 2. Significant differences or marginal differences were observed between the development of EI and all other variables.

|

|

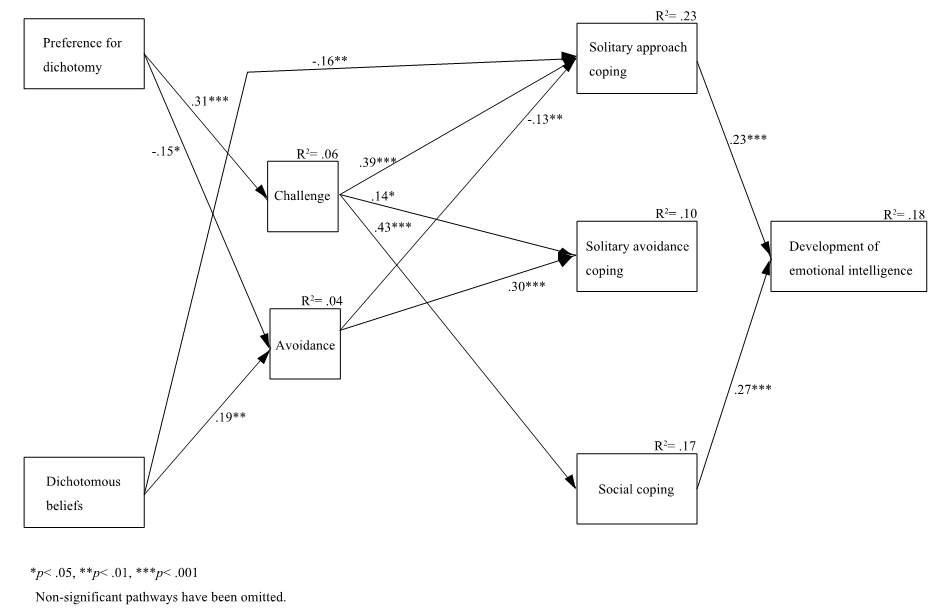

| Figure 1. The role of dichotomous thinking in the development of emotional intelligence |

3.2. Hypothetical Model

- Multiple regression analysis was used to analyze the hypothetical model. Factors included in the analysis were dichotomous thinking (preference for dichotomy, dichotomous beliefs, and profit-and-loss thinking), cognitive appraisal (challenge and avoidance), stress coping strategies (solitary approach coping, solitary avoidance coping, and social coping) and the development of EI through stress coping strategies.Results revealed that profit-and-loss thinking had no significant effect on any dependent variable. Preference for dichotomy had a significant positive effect on challenge-based cognitive appraisal and a significant negative effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal. Dichotomous beliefs had a significant positive effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal and a significant negative effect on solitary approach coping.Regarding the effects of cognitive appraisal on stress coping, challenge-based cognitive appraisal had a significant positive effect on solitary approach coping, solitary avoidance coping, and social coping. Avoidance-based cognitive appraisal had a significant negative effect on solitary approach coping but a positive effect on solitary avoidance coping.Both solitary approach coping and social coping had a significant positive effect on the development of EI.

4. Discussion

- The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of dichotomous thinking in the development of EI brought about by a stressful experience. We investigated a hypothetical model in which dichotomous thinking and cognitive appraisals entail coping, and the coping style adopted affects the development of EI. The college entrance examination was used as the stress-inducing experience.It was found that dichotomous thinking has a significant effect on cognitive appraisals, stress coping style, and the development of EI.

4.1. Effects of Dichotomous Thinking

- Preference for dichotomy had a significant positive effect on challenge-based cognitive appraisal, but a significant negative effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal. Preference for dichotomy refers to a thinking style that prefers distinctness, clarity, and conciseness, as opposed to ambiguity, obscurity, and vagueness. Examples of a preference for dichotomy are beliefs such as “all things work out better when likes and dislikes are clear” and “it works out best when even ambiguous things are made clear-cut” [9]. It is suggested that preference for dichotomy correlates with adaptive coping because it relates to the adaptive sides of perfectionism and regards interpersonal relationships as important [15].Conversely, dichotomous beliefs had a significant positive effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal but a significant negative effect on solitary approach coping. Dichotomous beliefs refer to thinking that anything in the world can be divided into two categories, such as “black or white,” “good or bad,” or “winner or loser”: demarcations centered around ideas such as “there are only ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in this world” and “I think all people can be divided into ‘winners’ or ‘losers’” [9]. It is suggested that dichotomous beliefs relate to the maladaptive elements of perfectionism, whereby one seeks immediate answers and is inclined to avoid a complicated situation [15]. In addition, it may relate to maladaptive elements such as negative appraisals toward others and self-criticism [15]. Thus, the present results are consistent with findings from previous studies.In summary, these findings suggest that a preference for dichotomy has adaptive elements, whereas dichotomous beliefs may be a maladaptive individual characteristic.

4.2. Relationship between Cognitive Appraisal, Stress Coping and Development of Emotional Intelligence

- Challenge-based appraisal of a stressful situation had a significant positive effect on solitary approach coping, solitary avoidance coping, and social coping. Avoidance-based cognitive appraisal had a significant negative effect on solitary approach coping, but a significant positive effect on solitary avoidance coping. These results suggest that challenge-based appraisal promotes adaptive coping, whereas avoidance-based appraisal promotes maladaptive coping.Solitary approach coping had a significant positive effect on the development of EI. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that appropriate stress coping promotes the development of EI [5].

5. Conclusions

- Preference for dichotomy had a significant positive effect on challenge-based cognitive appraisal, but a significant negative effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal. Additionally, dichotomous beliefs had a significant positive effect on avoidance-based cognitive appraisal, but a significant negative effect on solitary approach coping. These findings suggest that a “preference for dichotomy” is adaptive, whereas “dichotomous beliefs” are maladaptive. These findings clarify the importance of individual characteristics when attempting to understand the relationship between coping and the development of EI, and highlight the need to tailor support according to these characteristics in an applied setting. This study revealed that dichotomous beliefs influence the development of EI, and that adaptive coping and challenge-based cognitive appraisal are useful. Therefore, these findings suggest that in order to effectively develop EI, it may be useful to employ some intervention, such as cognitive restructuring, to change one’s dichotomous beliefs.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML