-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2015; 5(2): 25-31

doi:10.5923/j.health.20150502.01

Exclusive Breastfeeding and Its Associated Factors among Mothers in Sagamu, Southwest Nigeria

Oluwafolahan O. Sholeye 1, Olayinka A. Abosede 2, Albert A. Salako 1

1Department of Community Medicine and Primary Care, Obafemi Awolowo College of Health Sciences, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Sagamu, Nigeria

2Institute of Child Health and Primary Care, College of Medicine, University of Lagos / Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oluwafolahan O. Sholeye , Department of Community Medicine and Primary Care, Obafemi Awolowo College of Health Sciences, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Sagamu, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Breast milk provides the essential nutrients for infants less than six months of age and in addition to complementary foods, meets their nutritional needs in early childhood. Even though breastfeeding has been promoted severally, its practice has remained poor in many sub-Saharan African countries including Nigeria. This study therefore assessed the breastfeeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children less than two years of age in Sagamu, Nigeria. A cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out among 264 mothers of children less than two years of age, in Sagamu Township, Ogun State, Nigeria, selected via multi-stage sampling. Data was collected using validated semi-structured, interviewer-administered questionnaires and analyzed using SPSS Version 18. The modal age group of respondents was 30 - 39years; 96.2% were married and 42.4% were traders. All respondents breastfed their children, but only 56.1% practiced exclusive breastfeeding. About 25% were pressurized by relatives to stop exclusive breastfeeding. Respondents’ educational status (p<0.001), a feeling that breastfeeding had maternal benefits (p=0.044), feeling of protection against ovarian cancer (p=0.030) and nipple retraction (p=0.015) were associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. Reasons for not breastfeeding exclusively include: breast pain; a difficult work schedule, poor partner support and perceived weight loss. The breastfeeding practices of respondents were fair.. Mothers’ perception of breastfeeding benefits was associated with their practice. Adequate education of mothers and their partners will go a long way in enhancing optimal breastfeeding practices.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, exclusive, Children, Mothers, Sagamu, Factors

Cite this paper: Oluwafolahan O. Sholeye , Olayinka A. Abosede , Albert A. Salako , Exclusive Breastfeeding and Its Associated Factors among Mothers in Sagamu, Southwest Nigeria, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 25-31. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20150502.01.

1. Introduction

- Poor infant and young child feeding practices have been identified as a major contributor to the high burden of childhood morbidity and mortality in many countries. Early childhood morbidity and mortality in several sub-Saharan African countries have been unacceptably high, as a result of poor socio-economic conditions, low quality of child health services, and low level of maternal education and inadequate dietary intake [1, 2]. About 24% of children less than 5years were reported to be moderately or severely underweight in sub-Saharan Africa, according to UNICEF [3]. In West Africa, the proportion of underweight children under five years of age was 24%, as reported in the State of the World’s Children 2009. In Eastern and Southern Africa, the situation is almost the same, with 23% of under-fives being moderately or severely underweight [3].Breastfeeding remains the best option for infants in the first six months of life. It is a natural, cost-effective and evidenced-based nutritional activity that promotes the optimal wellbeing and survival of infants [4, 5]. Breast milk contains antibodies and essential nutrients, necessary for the promotion of health and adequate development of infants and very young children. Breastfeeding has been shown to protect infants from several morbidities in infancy and early childhood including acute respiratory infections, diarrhea and other gastrointestinal conditions [1, 4, 6, 7]. Researchers in a multi-centre cohort study, found non-breastfed infants to have a higher risk of dying compared with their predominantly breastfed counterparts [8]. According to the collaborative study team on breastfeeding and its role in prevention of childhood mortality in developing countries, exclusive breastfeeding significantly protected infants from dying from infectious diseases in the first few months of life [9]. The practice of exclusive breastfeeding has been less than optimal in many developing countries including Nigeria. More than 50% of Nigerian infants are fed complementary foods too early, which are often of very poor nutritional value [10]. In Nairobi, Kenya, complementary foods were introduced by 46.4% of the mothers studied, before the child was one month old [11]. Often times, these practices are as a result of traditional and modern perceptions of breastfeeding and its benefits, some of which are not based on scientific evidence [12-14]. A few misconceptions and inadequate information on breastfeeding have been documented in literature among mothers in developing countries, including those of sub-Saharan Africa [11, 15-19]. Several researchers have investigated breastfeeding practices in different communities of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. An insightful study reported a prevalence of 36% for exclusive breastfeeding among women in rural Bangladesh [19], which is similar to findings from a multiple indicator cluster survey also in Bangladesh, where 34.5% of mothers practiced exclusive breastfeeding [7]. Kishore et al reported a prevalence of 10% for exclusive breastfeeding in a community-based study, among mothers in rural Haryana, India [20]. A study among mothers in the slum areas of Dhaka, found only 5% of them practicing exclusive breastfeeding for 6months, while 53% of them breastfed exclusively in the first month [6]. In Nairobi, Kenya, a prevalence of 13.3% was reported for exclusive breastfeeding [11], which is lower than 33% reported by Nyanga et al [21] in a study, among women in Nyando district, Kenya. In Nigeria, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding has varied widely from 67% in Jos, north-central [22], 52.9% in Lagos, southwest [23] to37.3% in Anambra, southeast [24] and a national average of17%, as reported in the Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys of 2003 and 2013 [25, 26].According to UNICEF, only 15.1% of babies less than 6months of age were exclusively breastfeed, between 2008 and 2012 in Nigeria [27). The Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013 however reported a slightly higher prevalence (17%) for exclusive breastfeeding even though the average duration of the practice across the country was about 15days [26]. Several factors have been associated with breastfeeding practices of women in developing countries including maternal age, educational status, wealth quantile and place of delivery [19, 21, 24].Despite the existence and dissemination of the contents of the National Policy on Infant and Young Child Feeding, breastfeeding practices have remained poor. Child welfare clinics at various Primary Health Centres in Sagamu have partly implemented the action guidelines in the policy document by conducting weekly nutrition education sessions for mothers and other caregivers. This study therefore assessed the breastfeeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children less than 24 months of age in Sagamu, southwestern Nigeria.

2. Methods

- Study LocationSagamu Local Government Area (LGA) is one of the 20 LGAs in Ogun State, Southwestern Nigeria. It is an urban location comprising 15 wards, with peripheral rural sites. It has people of various tribes and livelihoods, within it. It serves as a transit zone between different parts of the country. There is a teaching hospital, a comprehensive health Centre and several private health facilities in Sagamu.Study DesignA cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out among mothers of children less than two years of age, accessing child health services atselected Primary Health Centres in Sagamu Local Government Area, Ogun State, Nigeria.Sample Size DeterminationThe sample size for this study was calculated using the formula for descriptive study,n = Z2 pq/d2 and a prevalence of 17% for exclusive breastfeeding (NPC/ICF, 2014)n = 2I6.82. The calculated sample size (n) was rounded up to 270, to allow for incomplete questionnaires and attrition.Sampling TechniqueRespondents were selected via multistage sampling technique. The first stage involved selection of three wards from the 15 existing wards in Sagamu LGA, by simple random sampling. The second stage involved the selection of PHCs from each selected ward, making a total of three PHCs in all. The third stage involved the selection of study participants at the pre-selected PHCs – Makun, Ajaka and Sabo - via systematic sampling.Study InstrumentA semi-structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. It was divided into three sections namely: socio-demography; perception and practice of breastfeeding and; factors associated with breastfeeding pattern. The questionnaire was pretested in a neighboring town, with similar characteristics as Sagamu, after which necessary adjustments were made.Data ManagementData analysis was carried out with the aid of IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.00. Questionnaires were scrutinized for completeness at the end of each day’s work. However, only 264 fully-completed questionnaires were analyzed. Relevant descriptive and inferential statistics were calculated. The level of significance (p) was set at 0.05. Results were presented as tables and prose.Ethical considerationsEthical approval was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital Sagamu and permission was obtained from the office e of the Director / Medical Officer of Health, Primary Health Care department, Sagamu LGA, Ogun State. Respondents’ informed consent was obtained prior to the onset of the study. Participants were free to withdraw from the study. All information obtained was treated with strict confidentiality.

3. Results

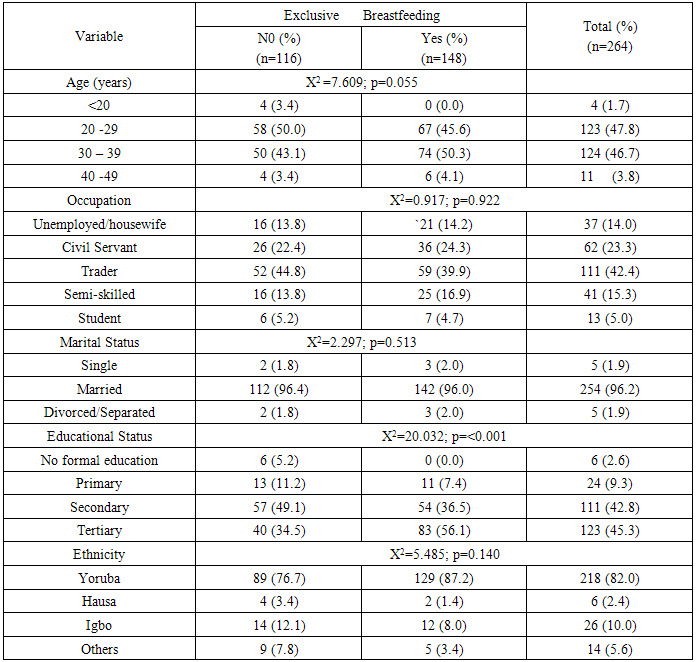

- Socio-demographic characteristics of respondentsRespondents were aged between 18 and 49 years, with the modal age group being 30 -39 years; only 1.6% was aged less than 20 years. Most respondents (42.4%) were traders, with only 5% being students. There was no significant difference in age p=0.055); occupation (p=0.922); marital status (p=0.513); religion (p=0.606) and ethnicity (p=0.140) between those practicing exclusive breastfeeding and those who were not. There was a significant difference (p<0.001) between the educational status of those breastfeeding exclusively and those who were not. See Table 1.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

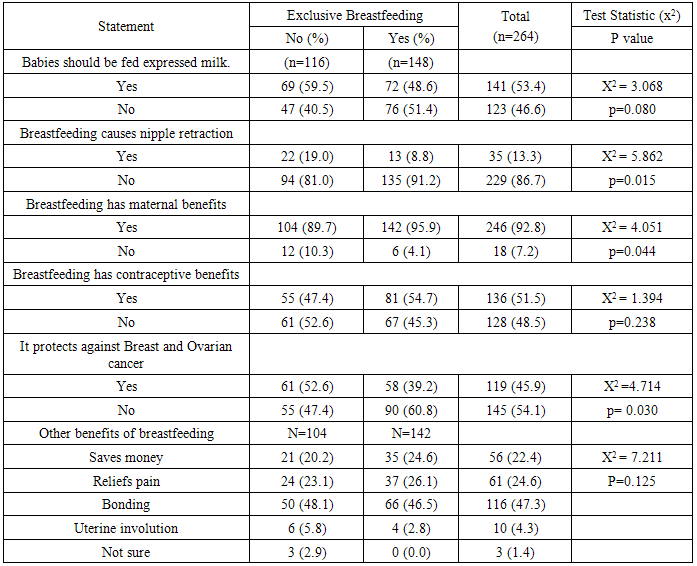

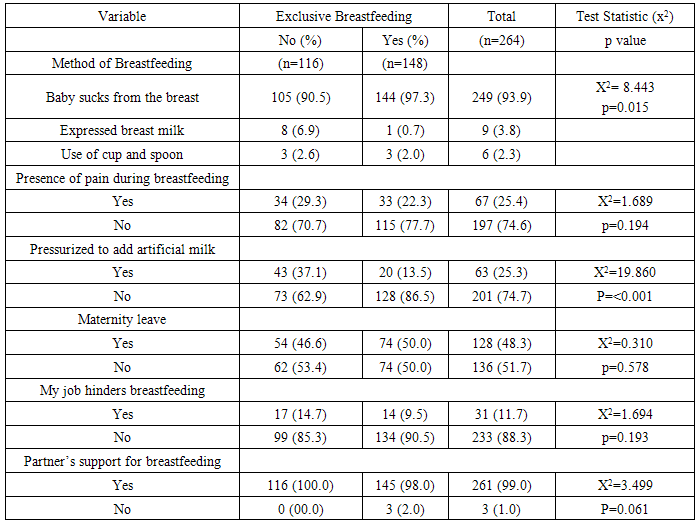

- Most respondents in this study were married women, aged between 20 and 29years, closely followed by those aged 30 -39years as reported in similar studies carried out in Kenya, India and Nigeria [20, 28, 29). Most respondents were married, as would be expected from a study of this nature. Trading was the commonest occupation among respondents, with very few being engaged in skilled labour, a finding comparable with that from Anambra, where 37.7% of the women studied were traders and 29% were full housewives [24]. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in this study (56.1%) is comparable with 60% reported among mothers in Calabar [16), 56.8% among rural Imo women [30), 54% in Pakistan [15] and 52.9% in Lagos [23]. It is however higher than the national prevalence of 17% and 13% reported in the NDHS 2013 and NDHS 2008 respectively [26, 31]. Several other studies reported much lower prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers of children less than five years old in Nigeria [5, 24, 32, 33] and other developing countries within and outside sub-Saharan Africa including Kenya [11, 21], India [20), Bangladesh [7, 19]. Researchers reported a prevalence of 5% for exclusive breastfeeding at 6months of age in Dhaka slums, although as high as 53% of mothers practiced it in the first month of their infants’ lives [6]. Also a study carried out in southwest Nigeria, found only 19% of respondents practicing exclusive breastfeeding [34). The observed differences between findings from this study and other published works could be as a result of the regular exposure of respondents in this study to nutrition education, particularly focused on infant and young child feeding at the different study sites. Maduforo et al [29] found 66% of respondents in Imo state, southeastern Nigeria, practicing exclusive breastfeeding, which is higher than the proportion obtained in our study. In this study only 3.8% of respondents fed their babies with expressed breast milk, a finding consistent with a report by the Ministry Of Health - Kenya, in which women do not usually express breast milk despite working away from home [35].The factors associated with breastfeeding practice in this study are similar to findings from other studies. Maternal educational status was associated with breast feeding practice which is similar to findings from Jos, North central Nigeria [22], Nyando district, Kenya [21] and in the developed world [36]. This however contrasts with findings from Sokoto, Northwestern Nigeria, where level of education had no association with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding [32]. As reported by researchers in Sokoto, occupation was not associated with breastfeeding practice in this study [32]. This however contrasts with several studies in which occupation (particularly paid employment), has been shown to be associated with breastfeeding practices and also documented to be a barrier to the practice of exclusive breastfeeding [21, 33, 35, 37]. In contrast with studies from Jos [22], Sokoto [32) and Kenya [21, 35] maternal age was not associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. Although about a quarter (25.4%) of respondents had experienced pain while breastfeeding, it was not associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding; a contrast with a previous study, which found breastfeeding practice to be associated with the mothers’ previous breastfeeding experience and self-efficacy with respect to breastfeeding [36].A cross-sectional study in Bangladesh, found type of delivery and wealth quantile to be associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding [19). In Kenya, a rapid qualitative assessment of infant and young child feeding attitudes and beliefs, revealed an association between social and economic factors and breastfeeding practices. Some mothers were under pressure to introduce complementary foods earlier than recommended, which is similar to findings from this study. Furthermore, a general lack of community support for adequate infant and young child feeding was noted [35). The survey also revealed the influence of health institutions on breastfeeding and other infant and young child feeding practices. Health workers were not routinely educating mothers on infant feeding in Kenya.The Innocenti Declaration, adopted 25years ago sought to address inappropriate infant and young child feeding practices, all over the world. About 15years later, the problems of sub-optimal breastfeeding, poor complimentary feeding and all forms of inappropriate infant and young child feeding practices still persist in many countries, including those of sub-Saharan Africa. Clearly-defined roles for health workers, health facilities and mothers are outlined in the document for implementation at both facility and community levels [38].The very poor nutritional performance of the country and the obvious need for evidence-based community and facility-level interventions, aimed at correcting the anomaly, must be addressed adequately. Health workers must be alive to their responsibilities of nutrition education and health promotion among mothers of under-fives and the general population. The strategies contained in the Innocenti Declaration and the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, though of over two decades, are still very much appropriate for today’s breastfeeding challenges. Health facilities must be seen to encourage the early initiation and maintenance of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers.

5. Conclusions

- The practice of exclusive was fair among respondents. Educational status, being under pressure to practice mixed feeding and method of breastfeeding were associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to express our gratitude to Dr O.E. Amoran, Dr O.A. Jeminusi, Mr Biodun and other staff of the Sagamu Community Centre for their support in data collection and preparation of the manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML