-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2014; 4(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.health.20140401.01

Sexual Behaviour and Risk Perception for HIV among Youth Attending the National Youth Service Camp, Ede, Osun State, Nigeria

Eyitope Oluseyi Amu

Department of Community Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, 360001, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Eyitope Oluseyi Amu , Department of Community Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, 360001, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The prevalence of HIV infection among Nigerian youth has been persistently high and risky sexual behavior has been implicated as a major factor responsible for this. Knowledge of their sexual behavior and HIV risk perception is important for programmatic interventions. The study was conducted to describe the sexual practices and risk perception for HIV among National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) members in Osun State. Study participants were tertiary institution graduates aged 20-29 years. The study employed a cross-sectional descriptive design. A pre-tested, self-administered, semi-structured questionnaire was used to elicit information from 500 corps members who were recruited by systematic random sampling at the NYSC orientation camp in Ede, Osun State, Nigeria. The results showed that 77.2% of the respondents had ever had sex, 86.6% of which were sexually active. Forty two percent had multiple sexual partners, 19.2% practiced transactional sex, while 58.1% used condom at last sex. The median age at first sex was 20 years. Only 16.6% felt that they had moderate to high risk of HIV infection. Good risk perception was associated with being sexually active (p=0.001), having multiple sexual partners (p< 0.001), transactional sex (p=0.002) and unprotected sex (p = 0.004). The prevalence of risky sexual behaviour among the respondents was high yet their risk perception for HIV was poor. Educational interventions that can empower youth to reasonably appreciate their risk of HIV and behavior change intervention that can make them to adopt safer sexual practices should be intensified among youth.

Keywords: Sexual behavior, Youth, HIV risk perception, National youth service scheme (NYSC)

Cite this paper: Eyitope Oluseyi Amu , Sexual Behaviour and Risk Perception for HIV among Youth Attending the National Youth Service Camp, Ede, Osun State, Nigeria, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20140401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- People’s perceived susceptibility to a disease affects their attitude towards taking preventive efforts at protecting themselves from it. Where people feel that they are at risk, they take steps to protect themselves. On the other hand, where people perceive themselves to have little or no risk of acquiring a disease, they throw caution to the winds when actually they might be at risk. There is no context in which these statements are truer than that of the HIV/AIDS scourge. In Sub-Saharan Africa, despite the fact that awareness about HIV/AIDS is high, there has not been a significant decline in risky sexual behavior, leading to continuous sexual transmission of HIV-1[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] It has been suggested that poor risk perception of contracting the disease contributes to the epidemic by making people not to be adequately motivated to make changes in their behavior.For young people in particular, the risk of HIV/AIDS may be hard to grasp. HIV has a long incubation period, so a person’s risky behaviour does not have immediately obvious consequences. They often cannot appreciate the adverse consequences of their actions because they lack the judgment that comes with experience[6, 7] Apart from the fact that they fail to appreciate their risks for HIV/AIDS, some even believe that they are invulnerable to the disease.[8] Studies conducted among youth within and outside Nigeria showed that young people do not perceive themselves to be at risk despite their involvement in many high risk behaviours. This feeling leads many young people to ignore the risk of infection and thus to take no precautions.[9, 10]Youth comprise about one-fifth of the world's population: there has never been a time in the history of the world that we have as many youth as at now.[11] In some developing countries where fertility rates are very high, they even comprise nearly two-fifths of such populations.[12] Youth are more likely to practice risky sexual behaviours but view their risk poorly. If their reproductive health challenges are not well handled now, they will further compound the existing problems - already HIV transmission rates are highest among them; likewise other sexually transmitted infections. In Nigeria and South Africa, youth show the highest HIV sero-prevalence rates and more than half of those newly infected are young people between 15 and 29 years.[5,13] Furthermore, studies have shown that the prevalence of risky sexual behaviour that can predispose to HIV infection is high in Nigerian tertiary institutions.[11, 14] These risky sexual behaviours are part of a larger pattern of young people’s health risk behaviour, including alcohol and drug use.[15, 16] There is anecdotal information that NYSC camps are a place of high prevalence of sexual activity and high risk sexual behaviour, yet there are hardly any empirical studies of sexual behaviour of youth corpers. In addition, youth corpers represent a rich mix of youth from different culture and background and are therefore suitable for the study. This study was therefore conducted to assess the sexual behaviour and HIV/AIDS risk perception of Nigerian youth in the NYSC camp in Ede, Osun State, Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

- The study location was the NYSC orientation camp Ede, Osun State, Nigeria. Ede, the headquarters of Ede North Local Government Area, is a peri-urban town close to Osogbo, the capital of Osun State. It is accessible from all parts of the state because of its good road networks.The NYSC Scheme is a one-year compulsory national service for new graduates of all tertiary institutions in Nigeria. These graduates represent different ethnic, socio-economic, cultural and religious groups in Nigeria. They are required to undergo a three-week orientation at the various NYSC camps located throughout the country, during which they undergo para-military training. Thereafter, they are posted to different parts of the states in which they were trained. While the scheme is compulsory for those between the ages of 20 and 30 years, it is optional for those above this age bracket. Majority of those posted to a particular state are usually non indigenes of the state.There were a total of two thousand five hundred corps members at Ede camp and these were divided into twenty platoons of one hundred and twenty five corps members each. Over each of the platoons was a platoon commandant. The study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design. The study population consisted of single male and female corps members on National Youth Service programme in Osun State. Married corps members and those who did not give their consent for the study were excluded.Assuming a 95% level of confidence, an estimate of youths who are already sexually experienced of 67.2% and a maximum acceptable difference from true proportion of 5%, the formula for estimating single proportions by Wingo et al, was used to obtain the minimum estimated sample size of 338.[14, 17] To compensate for improperly filled questionnaire that may have to be discarded, the sample size was increased by 25%. A total of 500 participants were eventually interviewed.Respondents were recruited using systematic sampling technique. There were a total of two thousand five hundred corps members in the camp, already divided into twenty platoons of one hundred and twenty five corps members each. Twenty-five corps members were recruited from each of the 20 platoons in order to make up the sample size of 500. The sampling interval was five, obtained by dividing 125 by 25.Corps members in each platoon already had serial numbers from 1 to 125. A number between 1 and 5 was then picked by ballot method. The corps member, whose NYSC number corresponded with that serial number, was recruited first. Multiples of five were added to the serial number each time a subsequent corps member was picked until twenty-five respondents had been chosen from each platoon. The same procedure was repeated for all the platoons. Married corps members and those unwilling to participate in the study were replaced by those next to them in the series.A pre-tested, semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire elicited information about respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, sexual behaviour and risk perception for HIV/AIDS. Approval for the research was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife. Permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Osun State NYSC Director. Written informed consent was obtained from each respondent prior to data collection. In order to ensure confidentiality, the questionnaires were completed privately and anonymously and were returned in envelopes designated for that purpose.Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15. Descriptive statistics were used to present respondents’ demographic variables, sexual behavior, selected indicators of risk of acquiring HIV, and perceptions of HIV risk status. Chi-square was used to elicit the relationship between sexual behaviour and risk perception; sexual behavior and condom use. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The outcome measures analyzed in the study were sexual behavior of respondents some of which were also the risk indicators, the perceived risk of HIV and the assessed risk of HIV. Sexual behavior (risk indicators) included previous sexual exposure, sexual activity in the preceding 12 months, multiple sexual partners in the preceding 12 months, sex in exchange for gifts and favours in the preceding 12 months (transactional sex) and unprotected sex (nonuse of condom) during the last sexual exposure in the preceding 12 months. In order to measure the Perceived risk of HIV, the respondents were asked to rate their likelihood of contracting HIV infection using a Likert-like scale of ‘no risk’, ‘little risk’, ‘moderate risk’ and ‘high risk’. The ratings were dichotomised into categories of ‘little or no risk’ and ‘moderate-to-high risk’. This was done in order to ascertain if respondents underestimated their risk of HIV infection or not, in relation to selected HIV risk indicators. In order to categorize the respondents’ risk of HIV as assessed by the investigator, a composite score that summarized the status of each respondent using the responses to the selected risk indicators for HIV infection was created. This measure assessed respondents’ risks on a scale of ‘high’ or ‘low’ and was used as the ‘gold standard’ against which to compare the respondents’ perceived risk statuses. Responses to each of four risk indicators were scored on a scale of 0–1; 0 when the risk indicator was absent; and 1 when the risk indicator was present. Scores were computed for each respondent; total and mean scores were also computed for all respondents. Those whose scores were more than the mean score were categorized as having a high risk of HIV infection while those whose scores were less than or equal to the mean score were categorized as having a low risk of infection. Respondents’ perceptions of ‘moderate to high’ risk was equated with ‘high assessed risk of infection’ and respondents’ perceptions of ‘little or no’ risk with ‘low assessed risk of infection’.Information obtained about sexual behaviour of the respondents could have been under reported or falsified due to the sensitive nature of the questions, even though adequate measures were taken to ensure confidentiality.

3. Results

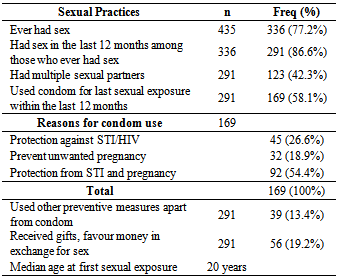

- A total of 435 out of 500 questionnaires administered were correctly filled and returned (response rate of 87.0%). The respondents were aged between 20-32 years; the mean age (SD) was 26.0 (2.2) years and most of them (90.2%) were in the 20-29 year old age group category. There were slightly more males (50.8%) than females (49.2%); 92.9% were Christians while 7.1% were Muslims. Most (72.9%) were from other tribes apart from the Yoruba ethnic group: Igbo 30.5%, Hausa 5.5% and other ethnic origins 36.9%. Forty three percent of the respondents studied Law, Social Sciences and Arts; 30.1% studied Pure, Applied and Health Sciences and 10% studied Accounting and Administration. The rest studied other courses.Table 1 shows the sexual behavior of the respondents. Three hundred and thirty six (77.2%) of the respondents were sexually experienced. Two hundred and ninety one (86.6%) of the sexually experienced respondents claimed to be sexually active, i.e had sex in the preceding 12 months. One hundred and twenty three (42.3%) and 56 (19.2%) of the sexually active respondents had multiple sexual partners and practiced transactional sex respectively. The types of partners included boy/girlfriends (81.8%), casual partners (25.2%), ‘live in’ partners (24.3%) and sex workers (7.0%). One hundred and sixty nine (58.1%) of the sexually active respondents claimed to have used condom at last sexual exposure and 54.4% out of these used it to prevent both sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy. The median age at first sexual intercourse was 20 years.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

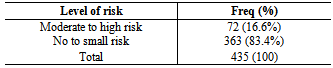

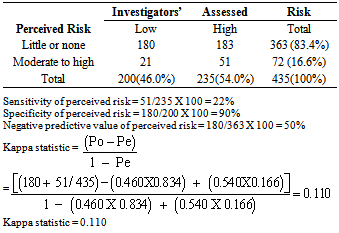

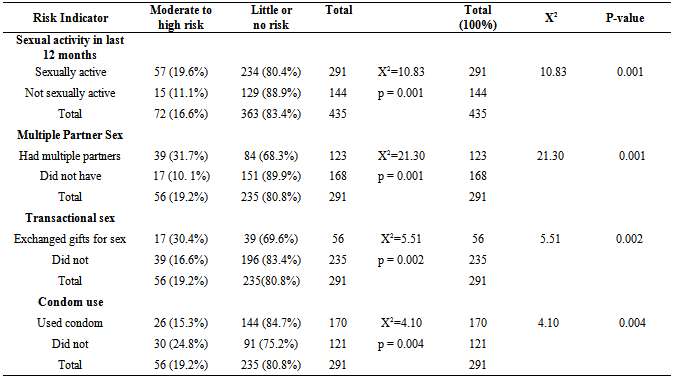

- The study revealed that about three-quarters of the respondents had initiated sexual activity (sexually experienced), similar to but higher than the findings of some other studies conducted among youth both within and outside Nigeria.[4,14,16,18] The median age at first sexual intercourse was 20 years and approximately nine out of ten respondents who had initiated sex, were sexually active in the last 12 months preceding the survey. This finding is higher than the 40.0, 68.3 and 76.0% reported among youth in Ibadan, Tanzania and Namibia respectively.[14,15,19] The older age group of respondents in this study might account for more respondents being sexually experienced and the higher median age at first sex. The longer period of 12 months used as reference period might account for more respondents being sexually active since other studies used reference periods of three to six months. These high levels of premarital sexual activities expose our youth to the dangers of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS and unwanted pregnancies among the female. Almost half of the sexually active respondents had multiple partners. This is consistent with the findings of studies conducted among youth within and outside Nigeria which equally reported that close to or slightly more than half of the youth studied had multiple sexual partners. [4,15,20] Having multiple sexual partners has considerable implications for sexual and reproductive health, including HIV and other STI transmission and is one of the factors driving the HIV scourge among youth.[21]About one-fifth of the sexually active respondents claimed to have received or given favours, gifts or money in exchange for sex. This is similar to the 24.2% reported among in-school adolescents in Ilorin, Nigeria, but lower than the 37.7 and 36.4% reported among some older youth in South West Nigeria and Tanzania respectively.[4,19,22] Economic hardship encourages young women to initiate sexual activity at early ages for economic reasons and to sustain the practice in older ages.[22,23] In addition, the desires to live big and use expensive things have also been documented.[21] In recent times, young men also receive gifts from well-to-do women in exchange for sex. Moreover, some of the young men patronize commercial sex workers and give money or gifts in exchange for sex with younger women.[18] Transactional sex, more widespread among youth, may put them at increased risk of contracting STIs, including HIV/AIDS. It may also put younger women at increased risk of pregnancy, childbearing as well as abortion.[24]Well over half of the respondents in this study used condom for their last sexual exposure. This finding is higher than the 48.0, 54.0 and 40.7% reported among youths in Ghana, Namibia and Tanzania respectively.[15,19,25] It is also higher than that reported among secondary school adolescents in Ghana and Ilorin, Nigeria.[18,22] That these respondents all had tertiary education should have made their rate of condom use correspond to their level of sexual activity. However, it did not; underscoring the need for continuous behaviour change communication among our educated youth. Correct and consistent use of condom substantially reduces the risk of STIs and also provides contraceptive benefits.Even though most of the respondents practiced risky sexual behaviours, less than a fifth perceived their risk of contracting HIV infection as being moderate to high. The remaining 8 out of ten felt that they had little or no risk of contracting the disease. The investigator’s assessment however showed that 54% were high risk while 46% were low risk showing some disparity between the respondent’s self-perceived risk and the investigators. The gold-standard against which participants’ perceived risk status was compared in this study were risk indicators selected by the researcher and so was not faultless. However, factors proven to be important in the judgment of risk for HIV (multiple partner sex, transactional sex and non-use of condom) were used as proxies for ‘confirmed risk’ statuses. Going by this standard, the sensitivity and specificity of 22.0 and 90.0% respectively of the respondents’ perceptions of their risk of HIV infection against the investigators assessed risk statuses were inaccurate. Furthermore, the negative predictive value of the students’ risk perceptions versus the assessed risk status was only 50%, and the Kappa statistic was 0.110. This suggests that the probability of a respondent who perceives himself/herself to be at little or no risk of HIV infection being truly at low risk is only 50%. This, together with the Kappa statistic, confirms a mismatch between perceived and assessed risk status.This mindset of poor risk perception for HIV infection despite high risk sexual behaviour is dangerous and prevents people from taking preventive behaviour. Youths especially, often fail to link their behaviour with poor disease outcomes. This is particularly true of the HIV infection which has a long incubation period. Infected youth might be symptom-free for several years and consequently think that they are immune or invulnerable to the disease (absent exempt error). They also tend to consider other people as being at higher risk than themselves (optimism bias). [2,7,10,26] All the risk indicators were significantly associated with respondents’ self-perceived risk of HIV infection as more of the respondents who practiced risky sexual behaviors perceived themselves as having moderate to high risk of HIV infection than those who did not. This is expected but differs from the reports of other studies in which only some of the risk factors influenced respondents’ perceived risk of HIV infection.[2,7,10,26] Some of the risk indicators used in this study however differed from those of the other studies.Educational interventions and behavior change communication should be intensified among youth in tertiary institutions. These would enable them to reasonably appreciate their risk of HIV and equally encourage them to adopt safer sexual practices that will make them less predisposed to HIV infection.

5. Conclusions

- Majority of the corps members had initiated sex and were also sexually active. An appreciable percentage of them also practiced risky sexual behaviour; yet less than a fifth perceived themselves to be at moderate to high risk of becoming infected with HIV. Good risk perception was associated with being sexually active; having multiple partners, having transactional sex and unprotected sexual intercourse.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author wishes to acknowledge the corps members who were interviewed; and Drs Bamidele J.O. and Odu O.O. who assisted in reading over and correcting the manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML