-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2013; 3(2): 15-20

doi:10.5923/j.health.20130302.02

Strengths and Difficulties of 30-month-olds and Features of the Caregiver-Child Interaction

Yuka Sugisawa1, Emiko Tanaka1, 2, Ryoji Shinohara1, Tong L1, Taeko Watanabe1, Yuko Yato3, Noriko Yamakawa4, Tokie Anme1

1Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, 305-8575, Japan

2D Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, 102-0083, Japan

3College of Letters, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, 603-8577, Japan

4Clinical Research Institute, Mie-Chuo Medical Center National Hospital Organization, Tsu, 514-1101, Japan

Correspondence to: Tokie Anme, Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, 305-8575, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this study is to examine the strengths and difficulties of 30-month-old children including various features of the caregiver-child interaction, which are considered aspects of social competence. The participants in the study, which was conducted as part of a Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) project, were 370 dyads of children (aged 30 months) and their caregivers. The participants completed two scales—the Interaction Rating Scale (IRS) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). There were significant correlations showing three characteristic patterns. First, there were negative correlations between the empathy, motor self-regulation, and emotional self-regulation domains of the IRS, and the hyperactivity-inattention domain of the SDQ. Second, there were also negative correlations between the autonomy, responsiveness, and empathy domains of the IRS and the peer problems domain of the SDQ. Third, there were positive correlations between the responsiveness, empathy, and motor self-regulation domains of the IRS and the prosocial behavior domain of the SDQ. In addition, with regard to the caregiver-related attributes measured by the IRS, there were negative correlations between the responsiveness-to-child domain of the IRS and the hyperactivity-inattention domain of the SDQ, and between the sensitivity to child domain of the IRS a total difficulties’ score of the SDQ.

Keywords: SDQ, Mother–Child Interaction, Childcare, Child Development, Japan

Cite this paper: Yuka Sugisawa, Emiko Tanaka, Ryoji Shinohara, Tong L, Taeko Watanabe, Yuko Yato, Noriko Yamakawa, Tokie Anme, Strengths and Difficulties of 30-month-olds and Features of the Caregiver-Child Interaction, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 15-20. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20130302.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Children’s social competence, which refers to their ability to understand others in the context of sociality and engage in smooth communication with them, has always attracted the attention of researchers. Within the realm of social behavior, what has particularly attracted researchers’ attention is the increase in impulsive behavior and social maladjustment in school-aged children and adolescents[1]. The development of children’s social competence is the outcome of complex interactions among factors related to the children themselves, their home environment, peer relationships, and the larger sociocultural environment[2]. Therefore, when children’s social competence is evaluated, it is necessary to consider the interaction between the children themselves and their social environment[3]. However, the methodology that considers children in conjunction with their social environment has not yet been well developed.A large number of indicators that measure the quality of children’s social environment and that focus on their caregivers’ interaction with them have been developed based on the belief that a child’s early rearing environment is significant for his/her development. Two instruments, namely, the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment[4] and Evaluation of EnvironmentalStimulation[5] are often used in research related to children’s development in the United States and Japan, respectively.The HOME and EES evaluate children’s rearing environment. Persons administering these instruments observe the everyday life of children in their natural social settings, which reflects the caregivers’ emotional and verbal responsiveness to the children, the caregivers’ acceptance of the children’s behavior, and so on. HOME has been adopted by studies conducted at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in the United States, and is also widely used in other countries. ESS has been used to investigate the effect of child care on children’s development in Japan[6],[7],[8],[9]. In addition, the Mediated Learning Experience Rating Scale (MLERS) has been used to assess the sensitivity and teaching of adults (caregivers and teachers) toward children through the observation of adult-child interaction[10].It is difficult to develop a method to objectively and comprehensively evaluate children’s social competence because of the sheer complexity of this ability. The tool that is currently used to assess social competence is the Social Skills Rating System[11], which was used in the study conducted at the NICHD. The SSRS evaluates children’s social competence on the basis of information provided by parents and teachers; however, this method of evaluating social competence suffers from the inevitable drawbacks of the possibility of parents and teachers missing out on or distorting information. The Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training (NCAST), which emphasizes the role of the caregiver in the development of social competence, was developed in the United States. The validity of this method had been confirmed for evaluating the communication and interactional patterns between caregiver and child[12]. In addition, this method also enables us to objectively evaluate in a short period of time the quality of child-rearing, the caregiver-child interaction, and the child’s behavior. However, considering that different cultures would have different effects on children’s social competence, this method, which was developed in the United States, cannot be used directly in Japan.Therefore, we developed a Japanese version of the Interaction Rating Scale (IRS) that could evaluate thechild-caregiver interactions in daily situations in Japan. We confirmed the discriminant validity of the IRS by evaluating a group of children that included those who had been diagnosed with developmental disorders and conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), and mental retardation (MR). Further, the inter-observer reliability of the IRS was found to be 85%[13].To improve children’s development, it is of extreme importance to obtain a clear picture of their strengths and difficulties and to examine the features of thecaregiver-child interaction as a kind of social competence. To measure the strengths and difficulties of children, we used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), which is a brief and established instrument. It includes items that measure strengths such as prosocial behavior, and provides a balanced evaluation of children’s social-emotional behavior. Various versions of the SDQ—a version for parents (caregivers), a version for teachers, and a self-report version—are available and all of them have been used worldwide.With the intention of obtaining some insights on children’s development, we examined the strengths and difficulties of 30-month-olds as well as the features of the caregiver-child interaction as a kind of social competence.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- The participants of the study were 370 dyads of children (aged 30 months) and their mothers, who participated in the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) project. However, the participants were reduced to 328 dyads (boys: 163, girls: 165) and their caregivers; those with missing demographic information were excluded from the sample. 30 month old children get skills to manage language and suitable timing to evaluate the difficulties and strength of it.In order to comply with the ethical standards laid down by the JST, before conducting the research, the families of all the participants signed informed consent forms and were made aware that they had the right to withdraw from the experiment at any time. As the infants were too young to provide informed consent, we carefully explained the purpose, content, and methods of the study to the caregivers and obtained their consent. In order to maintain confidentiality of the personal information of the participants, their personal information was collected anonymously, and a personal ID system was used to protect personal information. Further, all the image data were stored on a disk, which was password protected; only the researchers who were granted permission from the chairman were given access to the data.This study was approved by the ethics committee of the JST.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Interaction Rating Scale (IRS)

- We used the IRS to evaluate the features of the parent-child interaction as a kind of social competence.The IRS is a scale that measures the features of the caregiver-child interaction through observations of these interactions. The IRS has ten subscales. The five subscales related to the child are as follows: (1) autonomy, (2) responsiveness, (3) empathy, (4) motor self-regulation, and (5) emotional self-regulation. The five subscales related to the caregiver are as follows: (1) sensitivity to child, (2) responsiveness to child, (3) respect for the child’s autonomy, (4) social-emotional growth fostering, and (5) cognitive growth fostering. Each subscale related to the child consists of five items, and each subscale related to the caregiver consists of nine items; the total number of items in the scale is 70. Thirty-six items are based on the items of the NCAST, and we also referred to the HOME and SSRS when developing this version of the scale.The subscales of the IRS were evaluated as follows: a 5–10-minute video recording of the setting of the child-caregiver interaction (the child and caregiver playing with blocks and putting them in a box) was coded. The caregiver-child interactions were videotaped in a controlled laboratory environment. The recording was carried out in a room with five video cameras; one camera was placed at each of the four corners and one was placed in the central ceiling position. The dyads of children were escorted into a room (with dimensions of 4 4 meters) furnished with a small table and a small-sized chair meant for a child. The caregiver introduced herself to the child and interacted with the child in a natural manner, just as she would on a regular day.To score the behavior, 2 members of the research teamed coded the behaviors observed. A third child professional, who had no contact with the participants, also scored the behavior. The behavior of the children and caregiver during the caregiver-child interaction was coded as follows. If the child displayed the behavior described in the item, a score of 1 was given; conversely, if the child failed to display the behavior described in the item, a score of 0 was given. A child’s total score was the sum of the score that he/she received on all the subscales. A higher score indicated a higher level of development. The same method of coding was used to evaluate the caregivers’ behavior. The total IRS score was the total score of the child plus the total score of the caregiver.As mentioned in the introduction, we confirmed the discriminant validity of the IRS by evaluating a group that included children who were diagnosed as having developmental disorders and conditions such as ADHD, PDD, and MR. The inter-observer reliability of the scale was found to be 85%[13].

2.2.2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

- The SDQ is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire. Several versions of this questionnaire have been developed in order to meet the diverse needs of researchers, clinicians, and educational specialists. In this research, the caregivers completes a Japanese version of the SDQ. The SDQ consists of 25 items describing positive and negative attributes of children and adolescents that can be classified under five subscales, each consisting of five items. The five subscales are emotional symptoms, conduct problems,hyperactivity-inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. Each item has to be scored on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = certainly true). The subscale scores are computed by summing the scores on relevant items (after recoding reversed items; range: 0–10). Higher scores on the prosocial behavior subscale reflect greater strengths, whereas higher scores on the other four subscales reflect greater difficulties. A total difficulties score is calculated by summing the scores on the emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, and peer problems subscales (range: 0–40). There exists evidence indicating that the reliability and validity of the SDQ is adequate[14], [14],[15],[16]. In the present study, the reliability of the various SDQ subscales was found to be satisfactory, with the Cronbach alpha values being well above 0.70.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- Gender differences between the mean scores on the IRS and SDQ were determined using t-tests. In addition, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the relation among the scores on the subscales of the IRS and SDQ.The analysis was performed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) statistical package (Ver. 9.1).

3. Results

3.1. Gender Differences in the IRS and SDQ Scores

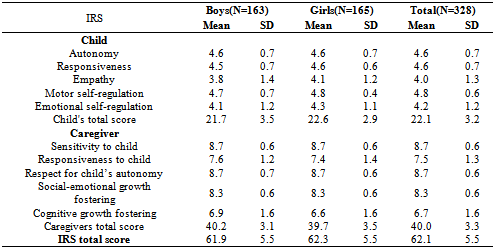

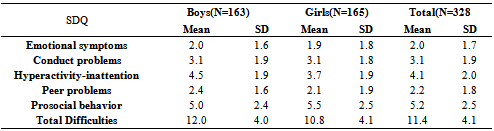

- Some significant gender differences were found in the scores on the IRS and SDQ subscales. The analysis of the scores on the IRS subscale revealed that girls were more developed than boys in the following domains (the girls’ scores have been provided first): empathy (p < .05): 4.1 (SD = 1.2) vs. 3.8 (SD = 1.4); motor self-regulation (p < .01): 4.8 (SD = 0.4) vs. 4.7 (SD = 0.7); emotional self-regulation (p < .05): 4.3 (SD = 1.1) vs. 4.1 (SD = 1.2); child’s total score: (p < .05): 22.6 (SD = 2.9) vs. 21.7 (SD = 3.5). (See Table 1)Analyses of the SDQ subscale scores indicated that particularly the hyperactivity-inattention (p < .001) and total difficulties (p < .05) scores were higher for boys than for girls; the mean scores of the boys and girls on the hyperactivity-inattention subscale were 4.5 (SD = 1.9) and 3.7 (SD = 1.9), respectively, and the mean total difficulty scores of the boys and girls were 12.0 (SD = 4.0) and 10.8 (SD = 4.8), respectively. Finally, the scores on the prosocial behavior subscale were lower (p < .05) for boys than for girls, the means being 5.0 (SD = 2.4) and 5.5 (SD = 2.5), respectively. (See Table 2)

|

|

3.2. Correlation between the IRS and SDQ Scores

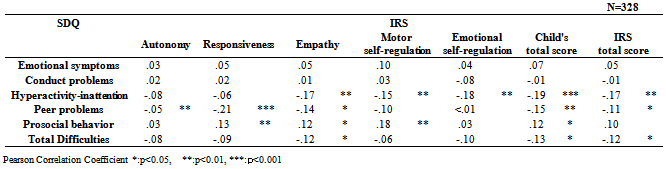

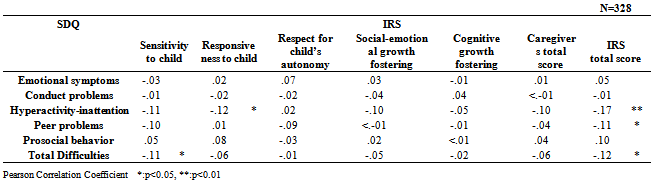

- An examination of the correlation between the IRS and SDQ scores (see Tables 3 and 4) revealed that the scores on the two scales were significantly correlated showing three characteristic patterns. First, there were correlations between some of the IRS domains, namely, empathy (r = –0.17, p < .01), motor self-regulation (r = –0.15, p < .01), and emotional self-regulation (–0.18, p < .01), and the hyperactivity-inattention domain of the SDQ. Second, there were correlations between the IRS domains of autonomy (–0.15, p < .01), responsiveness (–0.21, p < .001), and empathy (–0.14, p < .05), which were the child-related attributes in the caregiver-child interaction, and the domain of peer problems in the SDQ. Third, there were correlations between the responsiveness (0.13, p < .05), empathy (0.12, p < .05), and motor self-regulation (0.18, p < .01) domains of the IRS and the prosocial behavior domain of the SDQ. With regard to the attributes of the caregiver in the child-caregiver interaction measured by the IRS, there were correlations between the responsiveness to child and hyperactivity-inattention domains of the SDQ (–0.12, p < .05) and between the sensitivity to child domain of the IRS and the total difficulties score in the SDQ (–0.11, p < .05).

|

|

4. Discussion

- This study provides further evidence of the fact that in order to study children’s development, it is important to evaluate their strengths and difficulties along with various features of the caregiver-child interaction as a kind of social competence. First of all, the analysis of the IRS and SDQ subscale scores showed that girls obtained higher scores on some IRS child-related domains, which can be considered as types of social competence. These domains were empathy, motor self-regulation, emotional self-regulation, and the child’s total score. Further, girls had higher scores than boys on the prosocial behavior domain of the SDQ. These results are in good agreement with recent findings that there are gender differences in children’s social competence1. In addition, our research was conducted on boys and girls aged 30 months; therefore, the fact that girls develop faster than boys may have influenced the results. Further, the scores on the hyperactivity-inattention subscale and total difficulties scale of the SDQ were higher for boys than for girls. These results may be linked to the fact that boys are diagnosed more frequently than girls as having disorders such as ADHD and PDD.Secondly, there were significant correlations between some of the IRS domains, namely, empathy, motorself-regulation, emotional self-regulation, and the hyperactivity- inattention domain of the SDQ. When children with and without ADHD were compared, children with ADHD had lower levels of empathy and self-control in areas such as motor self-regulation and emotional self-regulation[13]. Although the evaluation of the SDQ has a subjective component as the ratings are performed by the caregivers, there is a possibility that the group of children who had high scores on the hyperactivity-inattention subscale of the SDQ includes some children who were already suspected of having ADHD.Third, the results indicated that there were associations between the IRS child-related attributes of autonomy, responsiveness, and empathy in the caregiver-child interaction, and the peer problems domain of the SDQ. These subscales of the IRS correspond to the cooperation and assertion subscales of the SSRS11, which were used in the NICHD study that measured children’s social behavior. What is evident here is that infant-caregiver interactions have an effect on patterns of adaptation[17]. Other studies have found relations between the security of attachment and preschool friendships[18]. Further, it has been found that children who have a history of healthy and positive attachment relationships tend to bully others less and also tend to be bullied less[19]. There is a possibility that our results are premonitory sign of these findings. Fourth, correlations were found between theresponsiveness, empathy, and motor self-regulation domains of the IRS and the prosocial behavior domain of the SDQ. It is believed that prosocial behavior stems from spontaneous motivation caused by empathy. Hamazaki[20] reported that children with high levels of empathy engage in a great deal of prosocial behavior compared to children with low levels of empathy. Strayer and Roberts[21], in a study that included parents, showed that empathy is positively correlated with prosocial behavior. Similarly, Sakurai[22], when asking children to complete a self-report questionnaire, showed that empathy is positively correlated with prosocial behavior. Therefore, our results suggest that the social competence based on empathy is related to prosocial behavior. Finally, with regard to the caregiver-related attributes in the IRS, there were correlations between the responsiveness to child and the hyperactivity-inattention domains of the SDQ, and between the sensitivity to child domain of the IRS and total difficulties scores in the SDQ. These results confirmed previous findings, which revealed that a responsive and sensitive caregiver positively affects a child’s development[23].While the present study did provide some valuable insights, it is also important to acknowledge its limitations. First, the study had a cross-sectional design and used correlation analysis, as a result of which no conclusions can be drawn about cause-and-effect relations. Second, the evaluations conducted while completing the SDQ have a subjective component, as the ratings are conducted by the caregiver. Despite these limitations, interesting findings emerged with regard to the gender differences in the IRS and SDQ scale scores. In addition, there were significant correlations between features of the caregiver-child interaction as a kind of social competence measured by IRS and SDQ scores which reported caregiver such as child’s social-emotional behavior. The IRS was able to evaluate child-related attributes in the caregiver-child interaction as a kind of social competence through observations lasting about 5 minutes that were validated by a third party who was a child health professional. Further, in the SDQ, the child’s behavioral problems and prosocial behavior have to be rated by the caregivers, who see their children’s behavior more broadly, including at home. The relations between the IRS and SDQ scores suggest that the IRS can be considered an established, valid screening instrument reflecting the child-related attributes in the caregiver-child interaction as a kind of social competence.For future studies, we can use IRS to clarify the features of the caregiver-child interaction, which can be considered as a kind of social competence and which can have implications for caregivers and child-care professionals. Further longitudinal studies are essential to explore the knowledge of child development, which consider other factors such as gender differences, physical development, child-care environment, and peer relationship.

5. Conclusions

- These results confirm previous findings and show that a responsive and sensitive caregiver is importantly related to the healthy development of a child.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research was supported by the R&D Area “Brain-Science & Society” of Japan Science and Technology Agency, Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society, and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (23330174, 24653134). We are grateful to all of the researchers in cooperative groups in this project, to the families who participated in the study. Our heartfelt appreciation goes to Hatsumi Yamamoto, Masatoshi Kawai, Hirosato Shiokawa, Tadahiko Maeda, Zentaro Yamagata, Mary McCall, and Mary McMahan for their able direction during the preparation of the manuscript. Their comments and suggestion were very valuable.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML