-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2011; 1(1): 8-15

doi: 10.5923/j.health.20110101.02

The Sleep of Children: an Inquiry into Factors that May Affect the Adequacy of Sleep among Children Attending Primary Schools in Macao

Cindy Sin U Leong 1, Thomas Kwok Shing Wong 2

1School of Health Science, Macao Polytechnic Institute, Macao

2Tung Wah College, Hong Kong

Correspondence to: Cindy Sin U Leong , School of Health Science, Macao Polytechnic Institute, Macao.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study was designed to measure many factors that might affect sleep among younger children (primary grades one through six) in public, Catholic, Protestant, and secular schools in Macao, a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People’s Republic of China. A comprehensive questionnaire was developed following interviews with 12 students and their parents in Macao. After proportional stratification and random stratified of the 59 primary schools in Macao (six geographical districts), 20 were chosen. A total of 5,358 students were selected randomly out of the approximately 29,300 primary students in Macao, of whom 4,101 (76.5%) actually participated. More than half (53.8%) of the students had a delayed bedtime because of tests or examinations, and 46.9% of the students indicated that heavy school work affected their bedtime. Well over half (62.2%) of the students reported that inadequate sleep affected their school performance. On weekends or holidays, 28.1% of the students postponed their wake-up time to 2 hours, and 40.9% of students postponed bedtime to play Internet games. These and other results from this study highlight the importance for school administration, school nurses, and parents of paying substantial attention to factors that may affect sleep in these children and others around the world.

Keywords: Sleep Behavior, Children, Sleep Duration, School Activity

Cite this paper: Cindy Sin U Leong , Thomas Kwok Shing Wong , "The Sleep of Children: an Inquiry into Factors that May Affect the Adequacy of Sleep among Children Attending Primary Schools in Macao", Journal of Health Science, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2011, pp. 8-15. doi: 10.5923/j.health.20110101.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The sleep behavior of children today differs considerably from that of previous generations; children nowadays sleep less as a result of their overly hectic lifestyles[1-5] In the United States, a large poll found that 24% of schoolchildren in grades one to six slept less than the recommended minimum of 10 or 11 hours[6] Studies in European countries, such as Finland, Greece, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, also found that students had insufficient time for sleep[7-8] In Asian countries like mainland China, Korea, and Japan, the phenomenon of inadequate sleep is much worse. For Chinese and Korean students, studies found an average sleep duration ranging between 4.86 and 7.5 hours[9-11] By way of explanation, Asian researchers have cited the students’ heavy school workload and their resultant need to study 8 to 9 hours in school and at home on a daily basis[12-13] In Asia, most students have to take extra tutoring to augment the information that they learn in schools. Children seldom show signs of sleepiness during daytime, but many reports show that more children are losing their concentration easily, are irritated more often, and increasingly show signs of attention deficit[14-16] Such children have been described by[17] as the “morningness” group, which means having an early bedtime and waking up early. Because so many children today delay going to bed because of unfinished school assignments or to study for tests or exams, their sleep-wake cycles on weekdays and weekends during the school semester should be compared to see whether there is any difference between them.In addition to school workload, both sleep habits and nap habits can affect sleep behavior. In the United States, a sleep poll found that 60% of school-aged children had a habit of bedtime reading, with mothers reading to children in the lower grades and older children reading on their own[7] This poll also found that 23% of children had their parents with them for companionship at bedtime. Playing soft music is another technique to induce children to have a quality sleep[6] Because no objective data related to children’s sleep behavior were available for Macao, a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People’s Republic of China, a survey was conducted among a wide spectrum of Macao schools.

2. Methods

2.1. Participant

- The six geographic districts of Macao have approximately 29,300 students enrolled in 59 primary schools. These 59 schools include public, subsidized, and private schools, and they may be Catholic, Protestant, or secular. After proportional stratification of the schools, 20 were randomly selected for participation. A total of 5,358 (18%) of the students from the 20 primary schools were randomly recruited to participate (in a single geographic district, the two kinds of religious schools and one kind of secular schools were grouped together before random selection). The 20 schools included four subsidized and one private Protestant school, six subsidized and one private Catholic school, two public, and six subsidized schools with no religious denomination. Selected participants were in grades one through six and ranged in age from 6 to 14 years. Because the survey was conducted in Chinese for grades one through grades six, participants and their parents from those grades had to know Chinese characters; if they did not, they were dropped from the survey.

2.2. Instrument

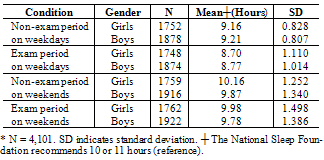

- The survey instrument was developed from the concepts and themes identified in an initial qualitative inquiry. In brief, pairs of one boy and one girl from each of the six grades (each pair from a different school) as well as either their mothers or fathers were interviewed to obtain their lived experience as the basis for the question-items. Those question-items with a content validity index (CVI) above 3 points were kept. For the Spearman correlation (rho), the maximum and minimum scores for test-retest reliability for the completed surveys in the developmental phase were 0.88 and 0.5, and the standard deviation (SD) was 0.11 as well as the mean score was 0.69, and on the whole the p-value was either less than 0.05 or less than 0.01. The intra-class correlation coefficient for test and retest reliability was 0.964, with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The P value was 0.000 for the two-way mixed effects measurement. For the nine categoreis/concepts that were developed the Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.61 to 0.90. An alpha greater than 0.5 was accepted for the survey. In the end, a total of 44 question-items were combined with an additional eight items that related to hours of sleep on weekdays and on weekends during test or exam periods or outside of those periods (Table 3).

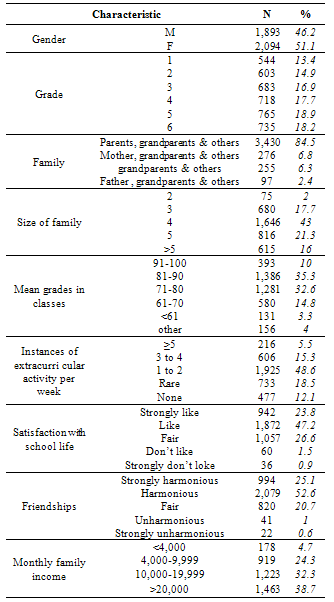

2.3. Procedure

- Random selection of students relied on the generation of student numbers by a random number generator system that was based on a report from the Youth and Education Bureau that included the total number of classes in each primary grade as well as the total number of students registered in one class in the previous year. In all, 1,893 (47.5%) boys and 2,094 (52.5%) girls participated in the survey, with an additional 114 participants failing to mention their gender. Thus, of 5,358 students who were randomly recruited, 4,101 actually participated, a response rate of 76.54%. All participants were given a package consisting of a detailed outline of the study, a consent form, and a survey questionnaire. The consent form was for obtaining the permission of parents or guardians to carry out the survey. Thus, parents and guardians were aware of the survey and able to assist the students in answering the question-items. Following approval of the research project by the board of ethics review of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the survey was initiated right away. After the required amounts of packages containing questionnaires were delivered to the schools, the teachers were asked to distribute the questionnaires to the individual students. The entire process took 2 ½ months from mid October to mid January from 2009 to 2010.

|

|

2.4. Results

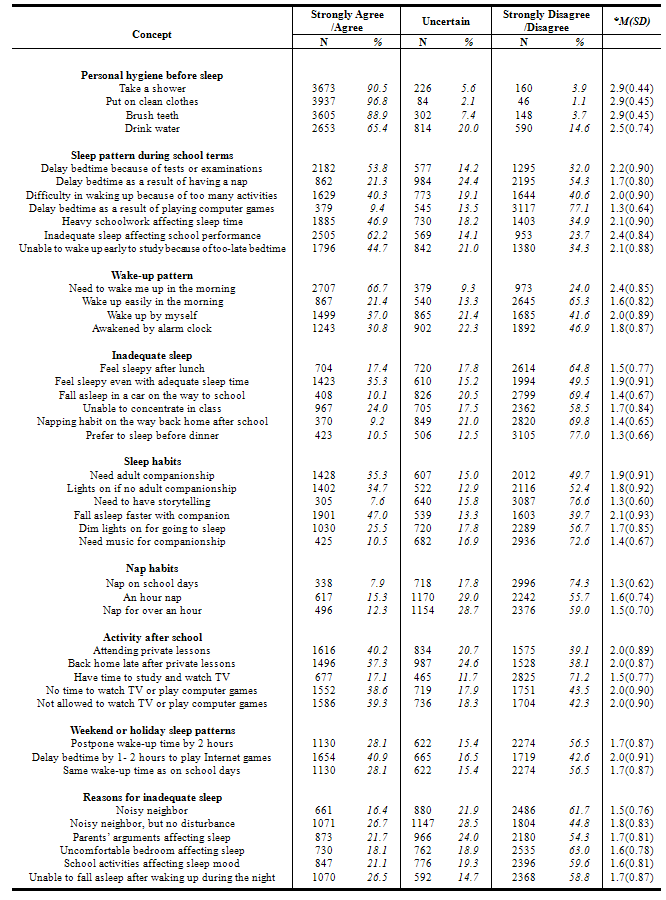

- The six unofficial geographical districts in Macao are Sao Louanco, Santo Antonio, N.S. de Fatima, Sao Lazaro, Se and Carmo. The 20 participating schools are from these districts with two and three schools involved. Fatima district is the area with seven schools conducted.The questionnaires for 1,716 (41.8%) of the 4,101 participants (247 participants did not mention who completed the survey) were completed by the students, while the remaining 58.2% were completed by the parents, grandparents, or other senior relatives. The number of participants was higher for the upper grades than for students registered in the lower grades (Table 1). Most students (84.5%) lived with parents, grandparents, and others. A four-member family unit was the most common (43.0%), with only 2.0% of students having a family of two. For 35.3% of the students their average grade in school performance was in the 81–90 range, while for 32.6% it was in the 71-80 range.Almost half (48.6%) of the students engaged in extracurricular activities after school one to two times per week, while 30.6% rarely or never participated in such activities and 5.5% engaged in such activity at least five times per week. In all, 71.0% of the students either liked or strongly liked their schools, and 77.7% of students enjoyed their friendships in school (“strongly harmonious” or “harmonious”). Overall, 95.3% of students were living in a family environment that was at least self-supporting with monthly family income more than MOP$4,000 (US$1.00 equivalent to MOP$8.05).For Table 2, a response of “strongly agree/agree” was interpreted as evidence that the student actually engaged in the activity of interest (e.g., “strongly agree/agree” for “attending private lessons” was interpreted to mean that the student in question attended private lessons. Conversely, in this example, a response of “strongly disagree/disagree” was interpreted to mean that the student did not attend private lessons).

2.4.1. Personal Hygiene before Sleep

- As shown in Table 2, 90.5% and 96.8% of students, respectively, took a shower and put on clean clothes before going to sleep. Eight of every nine students (88.9%) brushed their teeth before bedtime, and almost two-thirds (65.4%) drank water before bedtime.

2.4.2. Sleep Pattern during School Terms

- Over half (53.8%) of the students delayed their bedtime because of tests or examinations, and for an even larger proportion (62.2%) their school performance was affected by inadequate sleep. In all, 46.9% claimed that heavy schoolwork affected their sleep time, and 44.7% were unable to wake up early to study because of a late bedtime. The table indicates that 9.4% delayed their bedtime as a result of playing computer games, but 77.1% did not (13.5% were “uncertain”). Just over one-fifth (21.3%) delayed bedtime as a result of having a nap, but 54.3% did not (24.4% were uncertain).

2.4.3. Wake-Up Pattern

- Two-thirds (66.7%) of the students admitted they had to be awakened by others, and only 37.0% indicated they woke up by themselves. Some students (30.8%), mostly in the upper primary grades, woke up with the help of an alarm clock. Almost two-thirds (65.3%) of the students admitted that they were not easily awakened in the morning, even with the help of adults or an alarm clock.

2.4.4. Inadequate Sleep

- Just over one-third of the students (35.3%) felt sleepy even with adequate sleep (considered to be 9 hours according to their mean bedtime). Almost one-fourth (24.0%) of the students were unable to concentrate in class (it should be noted that lack of concentration could be attributed to reasons other than sleep, such as a noisy environment; information on reasons for inadequate sleep is reported separately below). Lower percentages felt sleepy after lunch (17.4%) and preferred to sleep before dinner (10.5%). In all, 10.1% of students napped on the way to school and 9.2% took a nap on the way back home.

2.4.5. Sleep and Nap Habits

- Overall, 35.3% of the students needed to be accompanied by an adult when going to bed. Almost half (47.0%) of the students admitted that they fell asleep faster when they had adult company at bedtime. About a quarter (25.5%) preferred the lights to be dimmed for going to sleep. Just 7.6% of the students needed to have stories read to them, and 10.5% needed music for companionship. Only a few students (7.9%) took a nap during school days; 15.3% of students napped for an hour and 12.3% napped over an hour.

2.4.6. Activity after School

- Essentially two-fifths (40.2%) of the students were required to attend private lessons after school. These lessons normally started around 4:00 pm and lasted for 2 to 4 hours. Similar percentages of students indicated that it was late when they got back home after finishing private lessons (37.3%), had no time to watch TV or play computer games (38.6%), and were not allowed to do either of the activities (39.3%). One study showed that 25% of children admitted watching TV and having exercise before bedtime may cause stimulation and prevent them initiation to sleep easier.

2.4.7. Weekend or Holiday Sleep Patterns

- As shown in Table 2, 28.1% of the students postponed their wake-up time by 2 hours on weekends and holidays, and 40.9% of students delayed their bedtime by 1–2 hours during those periods to play Internet games. Overall, 28.1% of the students kept the same wake-up time as on school days.

2.4.8. Reasons for Inadequate Sleep

- Although only about one-sixth (16.4%) of the students indicated that a noisy neighbor was a reason for inadequate sleep, 44.8% indicated that a noisy neighbor disturbed their sleep (i.e., they strongly disagreed/disagreed with the item “noisy neighbor, but no disturbance”). The two reasons for inadequate sleep that were positively endorsed by more than one-fourth of the students were “noisy neighbor, but no disturbance” (26.7%) and “unable to fall asleep after waking up during the night” (26.5%). For all six items in this concept the percentages for agreement did not go below 16.4% or exceed 26.7%.

|

2.4.9. Findings for Mean Duration of Sleep

- On average, boys did not reach the minimum of 10 or 11 hours recommended by the National Sleep Foundation regardless of the condition (Table 3). Girls reached the recommended sleep hours only in non-exam periods on weekends. For both boys and girls the fewest hours of sleep were achieved during exam periods on weekdays (means of 8.70 for girls and 8.77 for boys). Overall, the mean hours of sleep for students in the survey were well above 9 hours but well below 10 hours.

|

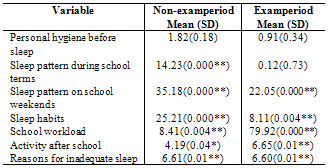

2.4.10. Impact of Selected Variables on Reaching 9 Hours of Sleep

- Chi-square was used to calculate the correlation between seven variables and reaching 9 hours of sleep (Table 4). This amount of sleep was used as the cut-point for duration so that more participants could be included in the calculations and because it was the mean for the students. Five of the seven variables (all but “Personal hygiene before sleep,” which was never significant, and “Sleep pattern during school terms”) showed a significant correlation on reaching 9 hours of sleep in both non-exam and exam periods on weekdays. The mean sleep of the students was reached and correlated with the high scores for the variables. For instance, the higher the scores in school workload, the harder to reach the mean 9 hours of sleep. The “Sleep pattern during school terms” was not significant correlation during exam periods.

3. Discussion

- This study of Macao schoolchildren suggests that several clusters of factors had an impact on the duration of their sleep. In addition, the study provides a good deal of information on the habits of the children that could logically be tied to their problems with getting enough sleep.

3.1. Sleep Habits and Reasons for Inadequate Sleep

- Many of these Macao children seemed to crave adult companionship around bedtime, and quite a few were no doubt uncomfortable in the dark. Adult companionship or co-sleeping to induce sleep used to be part of the culture of most Asian families, but this is not recommended currently, nor it is recommended in most Western countries[18-19] Co-sleeping means to accompany the child to bed in order to induce sleep for the first few hours, or even the whole period of sleep. Other reasons for co-sleeping might be that the children have difficulty in falling asleep or in getting back to sleep after waking up. The present study found that 35.3% of the students needed co-sleeping, while 26.5% had difficulty getting to sleep again after waking up during the night. In Macao, this difficulty might not be associated with co-sleeping. Rather, the small area of the house, the lifestyle, and sleeping arrangements might cause anxiety in the children. Notably, 34.7% of the students wanted a light on if there was no adult companionship. In terms of sleeping with their children, most parents understand that as their children go into adolescence, they cannot sleep with them even if the children ask them to. As for having a light on, the results in this study are reasonably compatible with a previous study that found the proportion of young people expressing this desire decreasing from 41.0% to 10.6%, starting at age 10 years and moving through 13 years[20]A poll taken in the United States found that an estimated 23% of American children had parents or caregivers putting them to bed[6] but this cannot be interpreted as co-sleeping. Notably, 47.0% of the children in the present study indicated they fell asleep faster with a companion, again suggesting a need for having someone with them at bedtime.

3.2. Sleep during School Days and Weekends

- The primary schools in Macao had four periods of exams during the school year. However, tests were frequent, as every week had at least 1 day for a Chinese test or dictation, 1 day for an English test or dictation, and 1 day for a basic mathematics test. That means there were tests on 3 of 5 school days. As was revealed by Table 3, the lowest mean hours of sleep for both boys and girls occurred in exam periods on weekdays. On weekends, both genders got smaller amounts of sleep in exam periods than in non-exam periods, although the difference for boys was small. Perhaps this means that even during weekends, the students needed more time to study in exam periods, or possibly they needed time for other matters. According to many sleep research studies, regular and consistent bedtime is essential on school days and on weekends[21-22] but this study found substantial differences between the two, with duration considerably greater on weekends. Knowing that their children have insufficient time to sleep on school days, parents or caregivers would likely prefer their children to sleep more on weekends. The present study found that 65.3% of the students were not eager to get up for school in the morning and 66.7% required adults to wake them up.

3.3. Effect of School Workload and Extracurricular Activity on Duration of Sleep

- This study found that both a heavy school workload and extracurricular activities influenced the duration of sleep (Table 4). Furthermore, the study found 62.2% of the children reporting that inadequate sleep affected their school performance. Previous research has indicated that getting adequate sleep assists in achieving good grades in school evaluations[23] In the present study, the school performances of girls were somewhat better than those of boys. These differences in grades might have had a relationship to hours of sleep. Although both girls and boys usually had 8.7 hours of sleep or more on weekdays, girls did better on weekends (that means for non-exam periods on weekends were 10.16 hours for girls and 9.87 hours for boys). Thus, it appears that girls were more likely than boys to use the time on weekends to cover their sleep debt, even the difference was only 0.29 hours or 17 minutes, which was in average. The phenomenon of boys sleeping fewer hours than girls has been supported by many previous reports[2], In the present study, more girls (10.97%) than boys (9.81%) engaged in three to five extracurricular activities per week, and more boys (6.45%) than girls (5.41%) had no extracurricular activities per week (data not shown in tables). Thus, it is safe to assume that the girls could be more exhausted by the end of the week and thus more in need of recharging their biological and psychological needs on weekends. Finally, while 24.7% of boys indicated that they delayed their bedtime by 1-2 hours on weekends in order to play Internet games, only 16.2% of girls did so, again suggesting a difference by gender.

3.4. Reasons for Inadequate Sleep

- This study indicates that the external and internal environments could have plagued some of the students as they sought to get enough sleep. External noises could be caused by traffic, hotel activities, or gambling activities, or by nocturnal entertainment in nearby living areas[24] The proportion of the students who cited noisy neighbors was 44.8% in this study, higher than the 35% reported in a study centered in the busy city of Guanzhou in mainland China[4] That survey reported for children aged 2 to 14 years and concerned being influenced by noise.Noises in the internal environment might involve some disturbances inside the apartment. The finding that for 21.7% of students their parents’ arguments affected their sleep was similar to research finding that the attitudes of parents and family and the way they managed stress management definitely affected their young and dependent children[25] A slightly smaller percentage of children (18.1%) in our study indicated that their uncomfortable bedroom affected their sleep. Perhaps for many of the children this was related to sharing a bed or bedroom with siblings or adults (we had no figures for these practices in our study but suspect that sharing was common). It is not too difficult to understand how having an uncomfortable bedroom that is too bright, or sharing a bed with siblings or parents, will have an impact on children’s ability to fall asleep[26]A crowded and noisy external or internal living environment has the potential to correlate with inadequate sleep, with children having difficulty falling asleep or waking during the night after initially falling asleep. According to available research, difficulty in falling asleep could be due to a history of having difficulty in falling asleep, worrying about school performance, stress and anxiety stimulated by school activities, or health problems or diseases[27-30]

3.5. Amount of Sleep

- The average weekday hours of sleep for girls (9.16 for non-exam periods, 8.70 hours for exam periods) and boys (9.21 and 8.77, respectively) are in the range of the recommendation for adolescents, which is at least 9 hours daily[31] Our students were younger, however, and thus their amounts of sleep should have been greater. The results for our study are similar to those for a community-based telephone survey in Hong Kong that reported an average of 8.8 hours for healthy schoolchildren aged 6 to 12 years[32] The similarity in results could reflect the proximity of the two study areas and the fact that they share culture and customs. The average duration recorded in our study was fewer than that in a research study in the U.S.A., where the average was 9.5 hours on school weekdays for students in the upper primary grades[23,33] Literature review also supported that sleep restriction is much obviously in the memory status of primary girls[34]

4. Conclusions

- This study strongly suggests that the full daily schedule of younger Macao schoolchildren is reflected in their struggle to get sufficient sleep. The school terms are overloaded with schoolwork, tests, and examinations. Even the parents can be faulted here. Children at the stage of development of our study children are quite dependent on their parents’ advice and demands. These youth may not know, or even understand, how to refuse the demands of adults. Judging from the results of our analysis, however, it is clear that these children are not being raised in a healthy climate[35] The responses to the questionnaire indicate that the duration of their sleep, the long hours they spend on schoolwork and the lack of relaxation time negatively affect their health and development[36] The results also show that the schools and some parents are somewhat ignorant about exactly what constitutes healthy sleep behavior. Early recognition and management of children sleep inadequate is very essential to their school performance[37] A program to educate parents about how to help their children get adequate sleep would go a long way toward ensuring that younger generations start building healthy behaviors that will result in quality sleep patterns.

4.1. Limitation

- Two government schools were selected from the same geographical district, which might have been related to other government schools not having enough students or refusing to have the survey conducted. Whether this was a problem for the survey cannot be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank the Macao Polytechnic Institute for funding this study (RP/ESS/2007). The author would also like to acknowledge all the participants conducting this survey. In addition, the researchers would like to thank Prof. Joanne Wai Jee CHUNG, and Assistant Prof. Jinghan CHEN from Department of Health and Physical Education, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, as well as Associate Prof. Ken GU from School of Health Sciences, Macao Polytechnic Institute.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML