-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Frontiers in Science

p-ISSN: 2166-6083 e-ISSN: 2166-6113

2017; 7(4): 57-64

doi:10.5923/j.fs.20170704.02

Formula for the Mass Spectrum of Charged Fermions and Bosons

Anatoli Kuznetsov

Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Correspondence to: Anatoli Kuznetsov, Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

We present the formula for the mass spectrum of the charged composite particles (CP). This formula includes the renormalized fine-structure constant α =1/128.330593928, the rest mass of a new electrically charged particle m = 156.3699214 eV/c2 and two quantum numbers of n and k. The half–integer and integer quantum number n is the projection of an orbital angular momentum electrically charged particle on the symmetry axis of the CP, and the integer k defines the magnetic charges of two Dirac magnetic monopoles, which have opposite signs of magnetic charges and masses. The presented model predicts the values of spins, masses, charge orbit radii and magnetic moments for an infinite number of charged fermions and bosons in the infinite range of mass.

Keywords: Composite models, Formula for the mass spectrum of elementary particles, Magnetic monopoles, Periodic dependence

Cite this paper: Anatoli Kuznetsov, Formula for the Mass Spectrum of Charged Fermions and Bosons, Frontiers in Science, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 57-64. doi: 10.5923/j.fs.20170704.02.

1. Introduction

- 120 years ago J. J. Thomson discovered the first subatomic particle – the electron [1]. Now several hundred subatomic particles are experimentally known, however, the question about the nature of the mass and the mass spectrum of subatomic particles is one of the most fundamental problems in physics, which unfortunately is not solved yet.By the early 20th century J. J. Thomson, A. M. Abraham, H. A. Lorentz and H. H. Poincaré had put forward a very promising idea concerning the electromagnetic nature of the electron mass in the framework of classical electrodynamics [1-4]. Lorentz has applied this idea for the extended electron model and has estimated quantity named the classical electron radius re equating electrostatic energy of the charge e to the electron rest energy: re = e2/mec2 = 2.817∗10-12 cm, where e and me are the electron charge and mass and c is the speed of light. However, the problem of electron mass has not found any consistent solution neither in classical electrodynamics nor later in quantum electrodynamics, mainly due to the divergence of electron self-energy in a point particle models and the problems with electron stability in extended particle models [5, 6].The presently successful standard model (SM) of modern particle physics considers three known families of the charged leptons (e, μ, τ) and the quarks (u, d, s, c, b, t) as the fundamental (elementary) point-like particles [7]. However, in this approach the SM cannot explain nor predict the possible numbers of the families of the fundamental particle, its masses and spins and it takes all of them outside the theory as experimentally known parameters. Thus, not all of us understand yet the reason of the muon existence and the muon-electron universality. Another theoretical problem is the parameters proliferation. The SM depends on more than twenty parameters, which are a priori arbitrary. The masses of leptons and quarks in the structure of this theory, as is assumed, are proportional to the coupling constants of the charged fermions with the scalar Higgs field [8]. As these coupling constants cannot be consistently defined in the Higgs theory, this mechanism actually does not provide any deeper understanding of the nature and the hierarchy of the mass of fundamental particles.It is reasonable that the solutions of the problem of mass can lie in the developing of a new fundamental theory on the basis of a new fundamental structural level which allows to explain naturally the known experimental results and in addition to predict new phenomena. As it is known from the history of physics, a similar problem was successfully solved at the beginning of the last century thanks to the discovery of the structure of atom and the development of the quantum theory.Various phenomenological models of composite subatomic particles have been proposed with the aim to reproduce quantum numbers of leptons and quarks [9-12]. An excellent analysis of this field has been presented by Lyons [13]. These models, however, in spite of some success in the classification of possible quantum states of composite particles (Quantum Numerology), have not solved the mass spectrum problem, because they have not contained any convincing dynamics at the fundamental level.To find the way to the future fundamental theory of subatomic particles it would be useful to find for particles at first an analogous to the Balmer-like formula or the Bohr theory for hydrogen atom. In this line Barut [14] has proposed the following formula for the muon mass calculation: mμ = me(1+(3/2)α-1), where input parameters are the electron mass me and the fine–structure constant α. This formula has been extended further by him, predicting in addition the masses of two heavy leptons [15]. Other empirical mass formulas for charged leptons and quarks have also been proposed [16, 17].In this work we present the formula for the mass spectrum of charged composite particles, which we have derived by using the Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization rule for an electrically charged particle moving on the circular orbit at relativistic velocity in the magnetic field of two Dirac magnetic monopoles. The details of our model and derivation of the mass formula will be presented in a future publication. This formula includes the renormalized fine-structure constant α = 1/128.330593928, the rest mass m = 156.3699214 eV/c2 of a new electrically charged particle and two quantum numbers n and k. The half-integer and integer quantum number n is the projection of the orbital angular momentum of an electrically charged particle on the symmetry axis of the CP and the integer number k defines the magnetic charges of two Dirac’s magnetic monopoles (MM), which have opposite signs of magnetic charges and masses.

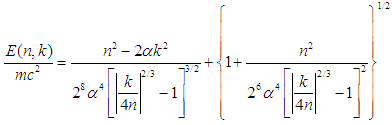

2. Mass Spectrum Formula of Charged Fermions and Bosons

- Our model of the charged composite particles includes two massive spineless Dirac’s magnetic monopoles (which having opposite signs of magnetic charges and masses) and a light spineless electrically charged particle moving on the circular orbit at relativistic velocity in magnetic field of two Dirac magnetic monopoles on the symmetry plain perpendicular to the magnetic monopoles axis.Let us briefly represent the method for deriving of the formula for the mass spectrum of the charged CP. In the framework of our model we take into account three contributions of energy into the rest energy of the charged CP: the repulsion energy between the moving charge and two magnetic monopoles, the Coulomb attraction energy between two magnetic monopoles and the total relativistic energy of the moving charged particle with the rest mass m. The contributions to the rest energy of the charged CP are dependent on the charge radius of the moving particle R(n, k) and/or on the distance between the two magnetic monopoles d(n, k). The equilibrium values of R(n, k) and d(n, k) can be determined on the basis of the two equilibrium equations for the two forces, acting on the moving charged particle (the centrifugal force and the centripetal force in the magnetic field of the magnetic monopoles) and the two forces, acting on the magnetic monopoles (the Coulomb attractive force between two magnetic monopoles and the repulsive force between the moving electric charge and the magnetic monopoles). On making up these two equations we have used the Bohr-Sommerfeld quantization rule for an electrically charged particle, moving on the circular orbit at relativistic velocity in the magnetic field of two Dirac magnetic monopoles. The obtained system of two equilibrium equations was solved analytically by giving the equilibrium value for R(n, k) and d(n, k) (see eq. (5)). Finally, substituting these expressions for R(n, k) and d(n, k) into the original equation for the rest mass of the charged CP and taking into account the modified the Dirac’s relation between the electric and magnetic charges, we have obtained the following formula for the mass spectrum of the charged fermions and bosons:

| (1) |

c is the fine-structure constant (

c is the fine-structure constant ( is Plank’s constant), n = 0, ±1/2, ±1, ±3/2… is the projection of the orbital angular momentum of the electrically charged particle on the symmetry axes of the CP and k = 0, ±1, ±2, ±3… is the quantum number, which defines the magnetic monopole charge of g through the Dirac relation modified by us eg/

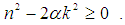

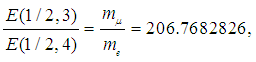

is Plank’s constant), n = 0, ±1/2, ±1, ±3/2… is the projection of the orbital angular momentum of the electrically charged particle on the symmetry axes of the CP and k = 0, ±1, ±2, ±3… is the quantum number, which defines the magnetic monopole charge of g through the Dirac relation modified by us eg/ c = k/4 [16].The first term in eq. (1) is the sum of two terms of the contribution of energy: the repulsion energy Er ∞ n2/α4 between the moving charge and two magnetic monopoles and the Coulomb attraction energy Ec ∞ −k2/α3 between two magnetic monopoles. The second term in eq. (1) Ek ∞ n/α2 is the total relativistic energy of the moving charged particle with the rest mass m. There is an obvious inequality Er, Ec >> Ek, because α ∼ 10-2 and thus the sum of repulsion and attraction energy terms gives the main contribution to the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP. In our model we have neglected the kinetic energy of two magnetic monopoles because of a large value of its masses M ≈ 108 GeV/c2 [19]. Due to the opposite signs of the mass of two Dirac magnetic monopoles both masses cancel each other and therefore do not give any contribution to the rest energy of the charged CP.According to equation (1) the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP is independent of the sign of the electric charge of the moving particle (because α ∞ e2) and of the signs of the quantum numbers n and k. Therefore, we have a twofold degeneracy connected with the opposite signs of ±n, corresponding to the clockwise and counterclockwise rotations of the electrically charged particle. This behaviour of the charged CP is similar to a two-dimensional quantum-rigid rotator, because both systems for each state with n > 0 have twofold degeneracy connected with the opposite signs of the projections of the orbital angular momentum ±n. Taking into account two possible signs of a moving particle mass ±m and a projection of the orbital angular momentum ±n, our model predicts two degenerate states ±n for the particle with positive rest energy E(n, k) > 0 for m > 0 and two degenerate states ±n for the antiparticle with negative rest energy E(n, k) < 0 for m < 0, which is consistent with the Dirac theory for the electron [20].Further, accepting (in agreement with the experiments) that the elementary particles in the quantum theory can be considered as scattering (metastable) states with positive rest energy and the antiparticles – as scattering states with negative rest energy (see also [21]), we receive the following condition from the numerator of the first term in equation (1)

c = k/4 [16].The first term in eq. (1) is the sum of two terms of the contribution of energy: the repulsion energy Er ∞ n2/α4 between the moving charge and two magnetic monopoles and the Coulomb attraction energy Ec ∞ −k2/α3 between two magnetic monopoles. The second term in eq. (1) Ek ∞ n/α2 is the total relativistic energy of the moving charged particle with the rest mass m. There is an obvious inequality Er, Ec >> Ek, because α ∼ 10-2 and thus the sum of repulsion and attraction energy terms gives the main contribution to the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP. In our model we have neglected the kinetic energy of two magnetic monopoles because of a large value of its masses M ≈ 108 GeV/c2 [19]. Due to the opposite signs of the mass of two Dirac magnetic monopoles both masses cancel each other and therefore do not give any contribution to the rest energy of the charged CP.According to equation (1) the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP is independent of the sign of the electric charge of the moving particle (because α ∞ e2) and of the signs of the quantum numbers n and k. Therefore, we have a twofold degeneracy connected with the opposite signs of ±n, corresponding to the clockwise and counterclockwise rotations of the electrically charged particle. This behaviour of the charged CP is similar to a two-dimensional quantum-rigid rotator, because both systems for each state with n > 0 have twofold degeneracy connected with the opposite signs of the projections of the orbital angular momentum ±n. Taking into account two possible signs of a moving particle mass ±m and a projection of the orbital angular momentum ±n, our model predicts two degenerate states ±n for the particle with positive rest energy E(n, k) > 0 for m > 0 and two degenerate states ±n for the antiparticle with negative rest energy E(n, k) < 0 for m < 0, which is consistent with the Dirac theory for the electron [20].Further, accepting (in agreement with the experiments) that the elementary particles in the quantum theory can be considered as scattering (metastable) states with positive rest energy and the antiparticles – as scattering states with negative rest energy (see also [21]), we receive the following condition from the numerator of the first term in equation (1) | (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

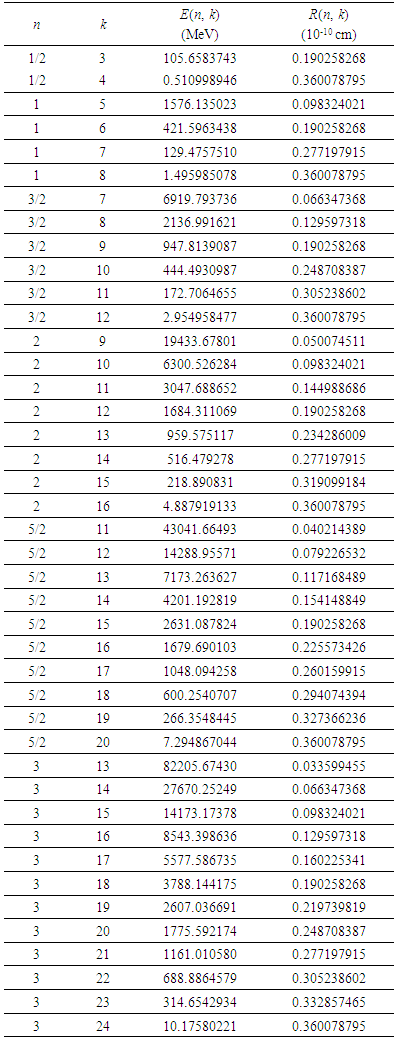

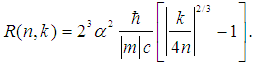

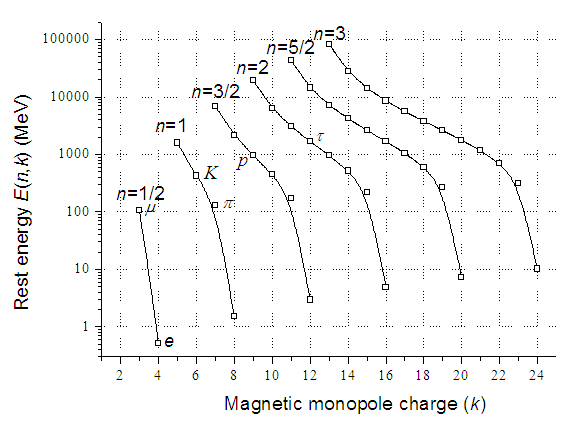

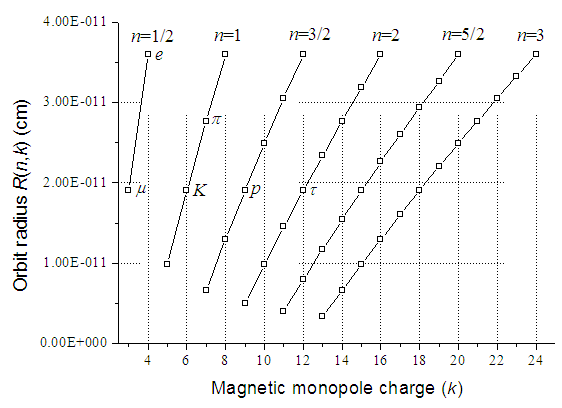

c = 1/137.035999139(31), obtained in the low energy limit [22]. The obtained value of α is in agreement with the value α = 1/128.5(25) extracted from the analysis of the electron-positron scattering at the momentum transfer Q2 = (57.66 GeV/c)2 [23] and also with the value α = 1/128.7862(87), obtained from the analysis of the empirical formulas for charged leptons [18].Using equation (1), the obtained value of the renormalized fine-structure constant α and the experimentally known electron mass, we have determined the rest mass of a new electrically charged particle m = 156.3699214 eV/c2. Thus, this new particle is very light even in comparison with the electron mass (m/me ≈ 0.000306).After estimating the values of these two parameters in equation (1) and assuming in the first approximation their constant values for all allowed values of quantum numbers n and k, we can calculate the rest masses E(n, k)/c2 of the charged fermions and bosons for any allowed pair n and k.The results of calculation for n = 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2, 3 and the corresponding values of k are listed in table 1 and also shown in fig. 1. As we can see from fig. 1, the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP has a characteristic periodic dependence as a function of the magnetic charge of magnetic monopoles. The rest energy of the charged CP E(n, k) achieves the maximum value at the beginning of every period when k has the minimum possible value for the fixed value of n. The increasing of k along the period the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP quickly decreases due to the negative contribution of the attraction energy Ec ∞ −k2/α3 between two magnetic monopoles. The transition to the next period through the increasing of n repeats the general behaviour of the rest energy E(n,k) and also includes the increasing of the maximal and minimal values of E(n, k) due to the bigger contribution of the repulsion energy Er ∞ n2/α4 between the moving of electrically charged particle and two magnetic monopoles. Note also that a similar periodicity exists also for the orbit radii R(n, k) of the mowing charge.The orbit radius of the mowing charge R(n, k) is defined by the form:

c = 1/137.035999139(31), obtained in the low energy limit [22]. The obtained value of α is in agreement with the value α = 1/128.5(25) extracted from the analysis of the electron-positron scattering at the momentum transfer Q2 = (57.66 GeV/c)2 [23] and also with the value α = 1/128.7862(87), obtained from the analysis of the empirical formulas for charged leptons [18].Using equation (1), the obtained value of the renormalized fine-structure constant α and the experimentally known electron mass, we have determined the rest mass of a new electrically charged particle m = 156.3699214 eV/c2. Thus, this new particle is very light even in comparison with the electron mass (m/me ≈ 0.000306).After estimating the values of these two parameters in equation (1) and assuming in the first approximation their constant values for all allowed values of quantum numbers n and k, we can calculate the rest masses E(n, k)/c2 of the charged fermions and bosons for any allowed pair n and k.The results of calculation for n = 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2, 3 and the corresponding values of k are listed in table 1 and also shown in fig. 1. As we can see from fig. 1, the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP has a characteristic periodic dependence as a function of the magnetic charge of magnetic monopoles. The rest energy of the charged CP E(n, k) achieves the maximum value at the beginning of every period when k has the minimum possible value for the fixed value of n. The increasing of k along the period the rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP quickly decreases due to the negative contribution of the attraction energy Ec ∞ −k2/α3 between two magnetic monopoles. The transition to the next period through the increasing of n repeats the general behaviour of the rest energy E(n,k) and also includes the increasing of the maximal and minimal values of E(n, k) due to the bigger contribution of the repulsion energy Er ∞ n2/α4 between the moving of electrically charged particle and two magnetic monopoles. Note also that a similar periodicity exists also for the orbit radii R(n, k) of the mowing charge.The orbit radius of the mowing charge R(n, k) is defined by the form: | (5) |

10-10 cm in every period for the same ratio value k/n = 8, when the rest energy E(n, k) of the charge CP reaches the minimum value, i. e. at the end of the period (see also figs. 1, 2 and table 1).

10-10 cm in every period for the same ratio value k/n = 8, when the rest energy E(n, k) of the charge CP reaches the minimum value, i. e. at the end of the period (see also figs. 1, 2 and table 1). 10-10 cm and it is only 7% less than the electron Compton wavelength λc =

10-10 cm and it is only 7% less than the electron Compton wavelength λc =  /mec = 0.3861592674

/mec = 0.3861592674 10-10 cm. For comparison, the radius of the muon charge is equal to 0.190258268

10-10 cm. For comparison, the radius of the muon charge is equal to 0.190258268 10-10 cm and it is approximately a hundred times bigger than the muon Compton wavelength 0.1857594307

10-10 cm and it is approximately a hundred times bigger than the muon Compton wavelength 0.1857594307 10-12 cm [22].

10-12 cm [22]. | Figure 1. The rest energy E(n, k) of the charged CP as a function of the quantum number k (which defines the magnetic charge of magnetic monopoles) for six values of the orbital angular momentum n = 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2, 3 electrically charged particle. Symbols e, μ, π, K, p, τ represent the position of the corresponding charged elementary particles on the graph |

| Figure 2. The charge orbit radius R(n, k) of the charged CP as function of the quantum number k (which defines the magnetic charge of magnetic monopoles) for six values of the orbital angular momentum n = 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2, 3 electrically charged particle. Symbols e, μ, π, K, p, τ represent the position of the corresponding charged elementary particles on the graph |

lepton in the first period of the charged CP, but we have found the place for it in the middle part of the fourth period (see below).The second period of the charged CP for n = 1 includes 4 bosons states in the energy interval 1.5 − 1576 MeV for k = 5, 6, 7, 8. This interval contains masses of

lepton in the first period of the charged CP, but we have found the place for it in the middle part of the fourth period (see below).The second period of the charged CP for n = 1 includes 4 bosons states in the energy interval 1.5 − 1576 MeV for k = 5, 6, 7, 8. This interval contains masses of  and

and  mesons at 139.57018(35) and 493.677(13) MeV/c2 [25], respectively. We accept for assignment

mesons at 139.57018(35) and 493.677(13) MeV/c2 [25], respectively. We accept for assignment  and

and  mesons to the charge CP states E(1, 7) = 129.5 MeV and E(1, 6) = 421.6 MeV, respectively. The distinction between the experimental and the predicted mass values for

mesons to the charge CP states E(1, 7) = 129.5 MeV and E(1, 6) = 421.6 MeV, respectively. The distinction between the experimental and the predicted mass values for  and

and  mesons can be reduced through the parameters renormalization in equation (1), i.e. by decreasing the fine-structure constant α at a level of 1.06% and 3.06% or by increasing the rest mass of a moving electrically charged particle at a level of 7.80% and 17.1%, respectively.As is known, the SM considers

mesons can be reduced through the parameters renormalization in equation (1), i.e. by decreasing the fine-structure constant α at a level of 1.06% and 3.06% or by increasing the rest mass of a moving electrically charged particle at a level of 7.80% and 17.1%, respectively.As is known, the SM considers  and

and  mesons as zero spin bosons. However, our model does not include the charged CP with zero spin because of the absence of a repulsive force between the moving electrically charged particle and two magnetic monopoles, which makes them unstable. The charged CP with the non-zero orbital angular momentum n of an electrically charged particle has the magnetic moment distinct from zero (see below), which in principle can be measured for

mesons as zero spin bosons. However, our model does not include the charged CP with zero spin because of the absence of a repulsive force between the moving electrically charged particle and two magnetic monopoles, which makes them unstable. The charged CP with the non-zero orbital angular momentum n of an electrically charged particle has the magnetic moment distinct from zero (see below), which in principle can be measured for  and

and  mesons in a strong magnetic field.The third period of the charged CP (n = 3/2) contains 6 fermions in the energy interval 3-6920 MeV for k = 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. The rest energy of the state E(3/2, 9) = 947.81 MeV matches with the proton rest energy 938.2720813(58) MeV with the accuracy of 1% [25], and we naturally connect this state with the proton. The small difference between the theoretical and experimental proton mass values can be reduced by means of tiny increasing in fine-structure constant α at a level of 0.192% or a small decreasing of the rest mass m of the electrically charged particle at a level of 1.02%.The ratio of the masses of proton and electron is an important dimensionless physical constant with the experimental value mp/me = 1836.15267389(17) [22]. According to equation (1), this ratio in our model is defined by the value of the renormalized fine-structure constant α, the values of quantum numbers n and k for proton and electron and it provides the theoretical value mp/me = 1854.8 in good agreement with the experimental data.As is known, the SM considers the proton as a strongly bounded state of three quarks (uud) and the electron as the structureless point-like particle and in this approach it cannot give the theoretical prediction of mp/me ratio. On the contrary, our model, being in line with [26], defines this ratio through the dimensionless constant of the electromagnetic interaction α, which in our model is a universal interaction constant for all charged CP.The other two problems are connected with the proton’s spin and magnetic moment. The SM describes the proton as a spin 1/2 particle with two possible spin projections sz = ±1/2. In our model the proton also has only two projections of the orbital angular momentum (spin) n = ±3/2. As is known, a point-like particle with electric charge e, rest mass m, and spin 1/2 in the Dirac theory has the intrinsic magnetic moment μD = e

mesons in a strong magnetic field.The third period of the charged CP (n = 3/2) contains 6 fermions in the energy interval 3-6920 MeV for k = 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. The rest energy of the state E(3/2, 9) = 947.81 MeV matches with the proton rest energy 938.2720813(58) MeV with the accuracy of 1% [25], and we naturally connect this state with the proton. The small difference between the theoretical and experimental proton mass values can be reduced by means of tiny increasing in fine-structure constant α at a level of 0.192% or a small decreasing of the rest mass m of the electrically charged particle at a level of 1.02%.The ratio of the masses of proton and electron is an important dimensionless physical constant with the experimental value mp/me = 1836.15267389(17) [22]. According to equation (1), this ratio in our model is defined by the value of the renormalized fine-structure constant α, the values of quantum numbers n and k for proton and electron and it provides the theoretical value mp/me = 1854.8 in good agreement with the experimental data.As is known, the SM considers the proton as a strongly bounded state of three quarks (uud) and the electron as the structureless point-like particle and in this approach it cannot give the theoretical prediction of mp/me ratio. On the contrary, our model, being in line with [26], defines this ratio through the dimensionless constant of the electromagnetic interaction α, which in our model is a universal interaction constant for all charged CP.The other two problems are connected with the proton’s spin and magnetic moment. The SM describes the proton as a spin 1/2 particle with two possible spin projections sz = ±1/2. In our model the proton also has only two projections of the orbital angular momentum (spin) n = ±3/2. As is known, a point-like particle with electric charge e, rest mass m, and spin 1/2 in the Dirac theory has the intrinsic magnetic moment μD = e /(2mc). CODATA gives for the proton experimental value of the magnetic moment μp = 2.7938473508(85)μD ≈ 3μD [22]. Our model predicts for the charged CP with an orbital angular momentum of the moving electrically charged particle n the value of the magnetic moment μ = 2nμD and, thus, for the proton (n = 3/2) the magnetic moment is given by μp = 3μD in agreement with experimental data.The proton charge orbit radius predicted in our model is R(3/2, 9) = 1.90258268

/(2mc). CODATA gives for the proton experimental value of the magnetic moment μp = 2.7938473508(85)μD ≈ 3μD [22]. Our model predicts for the charged CP with an orbital angular momentum of the moving electrically charged particle n the value of the magnetic moment μ = 2nμD and, thus, for the proton (n = 3/2) the magnetic moment is given by μp = 3μD in agreement with experimental data.The proton charge orbit radius predicted in our model is R(3/2, 9) = 1.90258268 10-11 cm, but the proton charge radius extracted from the analyses of the electron-proton elastic scattering is only Rp = 0.8759(77)

10-11 cm, but the proton charge radius extracted from the analyses of the electron-proton elastic scattering is only Rp = 0.8759(77)  10-13 cm [22, 27]. However, we assume that this value of the proton charge radius is necessary for increasing by the dimensionless factor 1/α ∼ 102. This factor can naturally occur through the change of the proton electromagnetic form factors due to the possible influence of the large magnetic charge of magnetic monopoles g ∼ e/α existing inside of every charged CP. Thus, after a correction by the factor 1/α the proton charge radius extracted from the electron-proton scattering data would reach the value Rp ≈ 1

10-13 cm [22, 27]. However, we assume that this value of the proton charge radius is necessary for increasing by the dimensionless factor 1/α ∼ 102. This factor can naturally occur through the change of the proton electromagnetic form factors due to the possible influence of the large magnetic charge of magnetic monopoles g ∼ e/α existing inside of every charged CP. Thus, after a correction by the factor 1/α the proton charge radius extracted from the electron-proton scattering data would reach the value Rp ≈ 1 10-11 cm in agreement with the result of our model.Experimentally, there are known only two practically stable charged fermions – the electron and the proton, which have the mean lifetimes τ ≥ 6.6

10-11 cm in agreement with the result of our model.Experimentally, there are known only two practically stable charged fermions – the electron and the proton, which have the mean lifetimes τ ≥ 6.6 1028 years [28] and τ ≥ 6.6

1028 years [28] and τ ≥ 6.6  1033 years [29], respectively. However, their positions in table 1 of the charged CP are different. The electron is located in the ground state of the first period of the charged CP and it has the absolute minimum of rest energy. But the proton is located in the middle part of the third period in the muon group (see table 1 and fig. 1). What is the physical reason of proton stability among six other states of this period and what dynamical mechanism prevents proton’s decay to the lower energy states of the charged CP, which have a common structure. This important problem deserves a further theoretical investigation, including our model as well.The fourth period (n = 2) includes 8 bosons in the rest energy interval 4.89 − 19434 MeV for k = 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. We assume the state E(2, 12) = 1684.3 MeV in the middle part of this period to be assigned on the

1033 years [29], respectively. However, their positions in table 1 of the charged CP are different. The electron is located in the ground state of the first period of the charged CP and it has the absolute minimum of rest energy. But the proton is located in the middle part of the third period in the muon group (see table 1 and fig. 1). What is the physical reason of proton stability among six other states of this period and what dynamical mechanism prevents proton’s decay to the lower energy states of the charged CP, which have a common structure. This important problem deserves a further theoretical investigation, including our model as well.The fourth period (n = 2) includes 8 bosons in the rest energy interval 4.89 − 19434 MeV for k = 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. We assume the state E(2, 12) = 1684.3 MeV in the middle part of this period to be assigned on the  particle with the experimental value of rest mass 1776.82(16) MeV/c2 [30]. The distinction (5.49%) between the theoretical and the experimental mass values of the

particle with the experimental value of rest mass 1776.82(16) MeV/c2 [30]. The distinction (5.49%) between the theoretical and the experimental mass values of the  particle can be reduced by decreasing the fine-structure constant α at a level of 1.02% or by increasing the rest mass m of the electrically charged particle at the level of 5.49%.The fifth period of the charged CP (n = 5/2) has 10 fermions in the rest energy interval 7.3 − 43042 MeV for k = 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.The sixth period (n = 3) of the charged CP includes 12 bosons states in the rest energy interval 10.2−82206 MeV for k = 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24.Three bosons states in the muon group (k/n = 6) at E(3, 18) = 3.79, E(4, 24) = 6.73 and E(6, 36) = 15.1 GeV are close to the rest mass of 3 new particles at 3.6, 7.3 and 15 GeV/c2 obtained by the CDF collaboration in the analysis of the multi-muon events [31]. These multi-muon events were produced in proton-antiproton interactions and discovered at the Fermilab Tevatron collider by the CDF collaboration [32]. It was supposed that the heavier new particles cascade-decay into lighter ones, whereas the lightest state decays into τ± pair with a lifetime of the order of 20 ps. In the framework of our model these processes are quite reasonable because all the interacting particles belong to some muon group and thus have the resonance condition for the processes of cascade-decay, because all particles have the same charge orbit radii of the moving charge and the distance between magnetic monopoles. Thus, the mass predictions from our model are in agreement with the results of the phenomenological analysis of multi-muon events by the CDF collaboration.In addition to bosons, the muon group contains also fermions (see table 1 and fig. 2). We have already connected the second fermion’s state of this group E(3/2, 9) = 0.9478 GeV to the proton. Another 4 fermions states in the muon group in the rest energy interval 2.5−13 GeV are: E(5/2, 15) = 2.63, E(7/2, 21) = 5.16, E(9/2, 27) = 8.59 and E(11/2, 33) = 12.7 GeV, respectively.The standard model of cosmology indicates that 3 stable particles - protons, neutrons and electrons, form the ordinary (baryonic) matter, which constitutes only ∼5% of the Universe mass. The remaining non-baryonic part of the Universe (with the unknown nature) belongs to dark matter ∼27% and dark energy ∼68% [33].During the search of dark matter (DM) particles the CoGeNT and DAMA collaboration [34] has found an excess of low energy events and the possibility that these events originate from the elastic scattering of a light mDM ∼5−10 GeV/c2 weakly interacting with the massive particle has been discussed. This mass interval is in agreement with the asymmetric models for dark matter generation, which predict the values of the DM mass at mDM ∼5−15 GeV/c2 [35].Thus, if 4 charged fermions from the muon group in the rest energy interval 2.5−13 GeV are stable particles (similar to the proton) and can create the stable neutral partners (similar to the neutron), then these new neutral particles can be the possible candidates for dark matter particles, predicted by our model.Let us go back to the group of ground states (k/n = 8) of the charged CP, i. e. the electron group. As we already mentioned, all these fermions and bosons of this group have the same charge orbit radii of the electrically charged particle and the same distance between magnetic monopoles. The rest energy for 13 members of this group is located in the range of 0.511 – 43.6 MeV. Below we consider the results of various experiments, which can be considered as the evidence of the emergence of particles of this group.The so-called heavy electrons with the rest mass m ≈ 3me ≈ 1.5 MeV/c2 and m ≈ 6me ≈ 3 MeV/c2 were found in air showers as particles that were more penetrating than electrons [36]. These particles in our model can be connected to the first boson state of the electron group with the rest energy E(1, 8) = 1.50 MeV and to the second fermion state of this group E(3/2, 12) = 2.95 MeV, respectively.A new particle with the mass m ≈ 11.4me ≈ 5.8 MeV/c2 was observed together with electrons in the cloud chamber [37]. We hope to connect this particle to the second boson state in the electron group E(2, 16) = 4.89 MeV.Further, when studying the optical characteristics of the pulsed laboratory synchrotron LIS-2 (the orbit radius 6 cm) [38], we noticed that a considerable part of the accelerated electrons (up to 100%) can drop out from synchronous mode acceleration. This effect was observed as sharp intensity reduction of synchrotron radiation when electrons reached the region of the maximal energy in the range Emax ≈ 37-40 MeV [39]. Now we are trying to explain this effect in the framework of our model as the revealing of the resonant transition of relativistic electrons, receiving the total energy equal to the rest energy of the charge CP, which belongs to the boson state of the electron group E(6, 48) = 37.4 MeV. The momentum excess of the accelerated electrons in this resonant transition is transferred to the magnetic field of the synchrotron practically without any energy transmission. This resonant transition is similar to the Mössbauer effect when in resonance recoil-free absorption of gamma photons by atomic nucleus the photon momentum is transferred to the whole crystal.

particle can be reduced by decreasing the fine-structure constant α at a level of 1.02% or by increasing the rest mass m of the electrically charged particle at the level of 5.49%.The fifth period of the charged CP (n = 5/2) has 10 fermions in the rest energy interval 7.3 − 43042 MeV for k = 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.The sixth period (n = 3) of the charged CP includes 12 bosons states in the rest energy interval 10.2−82206 MeV for k = 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24.Three bosons states in the muon group (k/n = 6) at E(3, 18) = 3.79, E(4, 24) = 6.73 and E(6, 36) = 15.1 GeV are close to the rest mass of 3 new particles at 3.6, 7.3 and 15 GeV/c2 obtained by the CDF collaboration in the analysis of the multi-muon events [31]. These multi-muon events were produced in proton-antiproton interactions and discovered at the Fermilab Tevatron collider by the CDF collaboration [32]. It was supposed that the heavier new particles cascade-decay into lighter ones, whereas the lightest state decays into τ± pair with a lifetime of the order of 20 ps. In the framework of our model these processes are quite reasonable because all the interacting particles belong to some muon group and thus have the resonance condition for the processes of cascade-decay, because all particles have the same charge orbit radii of the moving charge and the distance between magnetic monopoles. Thus, the mass predictions from our model are in agreement with the results of the phenomenological analysis of multi-muon events by the CDF collaboration.In addition to bosons, the muon group contains also fermions (see table 1 and fig. 2). We have already connected the second fermion’s state of this group E(3/2, 9) = 0.9478 GeV to the proton. Another 4 fermions states in the muon group in the rest energy interval 2.5−13 GeV are: E(5/2, 15) = 2.63, E(7/2, 21) = 5.16, E(9/2, 27) = 8.59 and E(11/2, 33) = 12.7 GeV, respectively.The standard model of cosmology indicates that 3 stable particles - protons, neutrons and electrons, form the ordinary (baryonic) matter, which constitutes only ∼5% of the Universe mass. The remaining non-baryonic part of the Universe (with the unknown nature) belongs to dark matter ∼27% and dark energy ∼68% [33].During the search of dark matter (DM) particles the CoGeNT and DAMA collaboration [34] has found an excess of low energy events and the possibility that these events originate from the elastic scattering of a light mDM ∼5−10 GeV/c2 weakly interacting with the massive particle has been discussed. This mass interval is in agreement with the asymmetric models for dark matter generation, which predict the values of the DM mass at mDM ∼5−15 GeV/c2 [35].Thus, if 4 charged fermions from the muon group in the rest energy interval 2.5−13 GeV are stable particles (similar to the proton) and can create the stable neutral partners (similar to the neutron), then these new neutral particles can be the possible candidates for dark matter particles, predicted by our model.Let us go back to the group of ground states (k/n = 8) of the charged CP, i. e. the electron group. As we already mentioned, all these fermions and bosons of this group have the same charge orbit radii of the electrically charged particle and the same distance between magnetic monopoles. The rest energy for 13 members of this group is located in the range of 0.511 – 43.6 MeV. Below we consider the results of various experiments, which can be considered as the evidence of the emergence of particles of this group.The so-called heavy electrons with the rest mass m ≈ 3me ≈ 1.5 MeV/c2 and m ≈ 6me ≈ 3 MeV/c2 were found in air showers as particles that were more penetrating than electrons [36]. These particles in our model can be connected to the first boson state of the electron group with the rest energy E(1, 8) = 1.50 MeV and to the second fermion state of this group E(3/2, 12) = 2.95 MeV, respectively.A new particle with the mass m ≈ 11.4me ≈ 5.8 MeV/c2 was observed together with electrons in the cloud chamber [37]. We hope to connect this particle to the second boson state in the electron group E(2, 16) = 4.89 MeV.Further, when studying the optical characteristics of the pulsed laboratory synchrotron LIS-2 (the orbit radius 6 cm) [38], we noticed that a considerable part of the accelerated electrons (up to 100%) can drop out from synchronous mode acceleration. This effect was observed as sharp intensity reduction of synchrotron radiation when electrons reached the region of the maximal energy in the range Emax ≈ 37-40 MeV [39]. Now we are trying to explain this effect in the framework of our model as the revealing of the resonant transition of relativistic electrons, receiving the total energy equal to the rest energy of the charge CP, which belongs to the boson state of the electron group E(6, 48) = 37.4 MeV. The momentum excess of the accelerated electrons in this resonant transition is transferred to the magnetic field of the synchrotron practically without any energy transmission. This resonant transition is similar to the Mössbauer effect when in resonance recoil-free absorption of gamma photons by atomic nucleus the photon momentum is transferred to the whole crystal.3. Conclusions

- In this work we have presented the formula for the mass spectrum of the composite charged fermions and bosons.This formula includes only two parameters – the mass of the new electrically charged particle m = 156.3699214 eV/c2 and the renormalized fine-structure constant α = 1/128.330593928, and also two quantum numbers n and k. The half-integer and integer quantum number n is the projection of the orbital angular momentum of electrically charged particle on the symmetry axis of the CP, and the integer quantum number k defines the magnetic charges of two Dirac magnetic monopoles.Taking into account two possible signs of the mass ±m of the moving particle and two projections of the orbital angular momentum (spin) ±n, our model predicts two degenerate states ±n for the particles with positive rest energy E(n, k) > 0 for m > 0 and two degenerate states ±n for the antiparticles with negative rest energy E(n, k) < 0 for m < 0 in agreement with the Dirac theory for the electron.In addition, our model shows the characteristic periodic dependence of the predicted masses and the charge orbit radius as the function of the magnetic charges of magnetic monopoles. Both periodic dependences are analogous to the periodicity of the first ionization energy and the atomic radius on the electric charge of the nucleus in the Mendeleev periodic table of chemical elements.Thus, the presented model predicts the values of spins, masses, charge orbit radii and magnetic moments for the infinite numbers of the charged fermions and bosons in the infinite range of mass.

References

| [1] | J. J. Thomson, “Cathode Rays”, Phil. Mag., vol. 44, 1-24, 1897. |

| [2] | M. Abraham, “Prinzipen der Dynamic des Elektrons”, Ann. Phys., vol. 315, 105-179, 1903. |

| [3] | H. A. Lorentz, “Electromagnetic Phenomena in a System Moving with Any Velocity Smaller than That of Light”, Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 6, 809-831, 1904. |

| [4] | H. Poincaré, “Sur la dynamique de l'électron”, Comptes Rendus, vol. 140, 1504-1508, 1905. |

| [5] | F. Rohrlich, Classical Charged Particles, World Scientific Publishing Company, New York, 2007. |

| [6] | J. L. Jimenéz, I. Campos, “MODELS OF THE CLASSICAL ELECTRON AFTER A CENTURY”, Found. Phys. Lett., vol. 12, 127-146, 1999. |

| [7] | F. Halzen, A. D. Martin, Qarks and Leptons: An Introductory Course in Modern Particle Physics, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1984. |

| [8] | P. W. Higgs, “Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 13, 508-509, 1964. |

| [9] | H. Harari, “A schematic model of quarks and leptons”, Phys. Lett. B, vol. 86, 83-86, 1979. |

| [10] | M. A. Shupe, “A composite model of leptons and quarks”, Phys. Lett. B, vol. 86, 87-92, 1979. |

| [11] | E. J. Squires, “Qdd: A Model of Quarks and Leptons”, Phys. Lett. B, vol. 94, 54, 1980. |

| [12] | J.-J. Dunge, S. Fedriksson and J. Hansson, “Preon trinity − A schematic model of leptons, quarks and heavy vector bosons”, Europhys. Lett., vol. 60, 188-194, 2002. |

| [13] | L. Lyons, “An Introduction to the Possible Substructure of Quarks and Leptons”, Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics, vol. 10, 227-304, 1983. |

| [14] | A. O. Barut, “THE MASS OF THE MUON”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 73B, 310-312, 1978. |

| [15] | A. O. Barut, “Lepton mass Formula”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 42, 1251, 1979. |

| [16] | P. A. M. Dirac “Quantised Singularities in the Electromagnetic Field”, Proc. Roy. Soc., vol. A 133, 60-72, 1931. |

| [17] | Y. Koide, “Charged lepton mass relations in a supersymmetric Yukawaon model”, Phys. Rev. D., vol. 78, 093006, 2008; arXiv: 0811.3470 [hep-ph]. |

| [18] | K. Loch, “A new empirical approach to quark and lepton masses”, viXra: 1702.0332 [High Energy Particle Physics]. |

| [19] | A. S. Kuznetsov, “Possible gravitoelectric dipole moment of neutrinos, atmospheric and solar neutrino anomalies”, Physics Essays, vol. 21, 144-150, 2008. |

| [20] | P. A. M. Dirac, “The quantum theory of the electron”, Proc. Roy. Soc., vol. A 117, 610-624, 1928. |

| [21] | D. J. Griffiths, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed., Cambridge CB2 8BC, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2017, Chapt. 2, p. 68. |

| [22] | P. J. Mohr, D. B. Newell and B. N. Taylor, “CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2014”, Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 88, 035009, 2016. |

| [23] | I. Levine et al., “Measurement of the Electromagnetic Coupling at Large Momentum Transfer”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 78, 424-427, 1997. |

| [24] | D. I. Mendeleev, “The Correlation of the Properties and Atomic Weights of the Elements”, J. Russ. Phys. Chem. Soc., vol. 1, 60-77, 1869; “Uber die Beziehungen der Eigenschaften zu den Atomgewichten der Elemente”, Z. Chem., vol. 12, 405-406, 1869. |

| [25] | C. Patrignani et al., (Particle Data Group), Chin. Phys. C, vol. 40, 100001, 2016. |

| [26] | M. J. MacGregor, The power of α Electron Particle Generation with α−Quantized Lifetimees and Masses, World Scientific, Singapore, 2007, Chapt. 1, p. 64. |

| [27] | R.W. McAllister, R. Hofstadter, “Elastic Scattering of 188-Mev Electrons from the Proton and the Alpha Particle”, Phys. Rev., vol. 102, 851- 856, 1956; Kirk P. N. et al., “Elastic Electron-Proton Scattering at Large Four-Momentum Transfer”, Phys. Rev. D, vol. 8, 63-91, 1973. |

| [28] | M. Agostini et al., “Test of Electric Charge Conservation with Borexino”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 115, 231802, 2015. |

| [29] | H. Nishino et al., “Search for Proton Decay via p→e+π0 and p→μ+π0 in a Large Water Cherenkov Detector”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 102, 141801, 2009. |

| [30] | M.L. Perl et al., “Evidence for Anomalous Lepton Production in e+-e− Annihilation ”, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 35, 1489, 1975. |

| [31] | P. Giromini et al., “Phenomenological interpretation of the multi-muon events reported by the CDF collaboration”, arXiv: 0810.5730 [hep-ph]. |

| [32] | T. Aaltonen et al., “Study of multi-muon events produced in interactions at TeV”, Eur. Phys. J. C, vol. 68, 109-118, 2010); arXiv: 0810.5357 [hep-ex]. |

| [33] | J. Einasto, A. Kaasik, E. Saar, “Dynamic evidence on massive coronas of galaxies”, Nature, vol. 250, 309-310, 1974; J. Einasto, “Dark Matter”, arXiv: 0901.0632 [astro-ph]. |

| [34] | A. L. Fitzpatrick, D. Hooper and K. M. Zurek, “Implications of CoGeNT and DAMA for light WIMP dark matter”, Phys. Rev. D., vol. 81, 115005-1−115005-14, 2010. |

| [35] | D. E. Kaplan, M. A. Luty and K. M. Zurek K, “Asymmetric Dark Matter”, Phys. Rev. D., vol. 79, 115016, 2009. |

| [36] | L. Janossy and C. B. A. McCUSKER, “The Nature of Penetrating Particles in Air Showers”, Nature, vol. 163, 181-183, 1949. |

| [37] | E. W. Cowan, “Evidence for the Existence of a Low-Mass Mesotron”, SCIENCE, vol. 108, 534-535, 1948. |

| [38] | A. S. Kuznetsov, “Asymmetry of the Angular Distribution of the II-Component of Synchrotron Radiation (SR), Caused by Electron Spin Polarization along the Acceleration Vector”, Europhys. Lett., vol. 21 (5), 545-549, 1993. |

| [39] | A. Kuznetsov and E. Vilt, “Optical characteristics of the LIS-2 pulsed synchrotron”, Nucl. Inst. Meth. in Physics Research, vol. A308, 92-93, 1991. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML