-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Frontiers in Science

p-ISSN: 2166-6083 e-ISSN: 2166-6113

2014; 4(1): 12-19

doi:10.5923/j.fs.20140401.03

Production Characteristics of Smallholder Dairy Farming in the Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone, Uganda

Andrew M. Atuhaire1, 2, S. Mugerwa1, J. M. Kabirizi1, S. Okello2, F. Kabi3

1National Agricultural Research Institute (NARO), National Livestock Resources Research Institute (NaLIRRI), P. O. Box 96, Tororo, Uganda

2Department of Livestock and Industrial Resources, College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Resources and Bio-security., Makerere University, P. O. Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda

3Department of Agricultural Production, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences., Makerere University, P. O. Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda

Correspondence to: Andrew M. Atuhaire, National Agricultural Research Institute (NARO), National Livestock Resources Research Institute (NaLIRRI), P. O. Box 96, Tororo, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Smallholder dairy farming is increasingly becoming an important source of livelihoods for small scale dwellers in Lake Victoria agro-ecological Zone (LVZ) in Uganda. A study was carried out in Buikwe, Jinja and Mayuge Districts in LVZ of Uganda, with the objective of characterizing smallholder dairy farming. A total of 126 smallholder dairy farmers were interviewed using structured, semi-structured questionnaires and focus group discussions between September and November 2013. Data collected included; household demographics, challenges in smallholder dairy farming systems, available feed resources, labour distribution, milk production and marketing. The study revealed that households in Buikwe district had relatively larger herd size (4.29±0.864 head of cattle) compared to other districts. Natural pastures (p<0.05, df=4) were ranked as the main source of feed. Smallholder dairy farmers in Jinja ranked agro-industrial by-products as a major alternative feed resource supplemented to natural pastures while farmers in Buikwe and Mayuge utilized crop residues during periods of feed scarcity. Low farm gate price of milk that invariably fluctuated with season in all districts were the major (P<0.05, df = 4) challenges faced by the smallholder dairy farmers. Feed scarcity (p=0.001, df=4) was ranked as the major challenge. The study, therefore, provided basic information on production characteristics of smallholder dairy farming system from farmer’s point of view that could benchmark strategic research interventions to address declining smallholder dairy farmers’ productivity.

Keywords: Dairy cattle, Labour distribution, Smallholder, Uganda

Cite this paper: Andrew M. Atuhaire, S. Mugerwa, J. M. Kabirizi, S. Okello, F. Kabi, Production Characteristics of Smallholder Dairy Farming in the Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone, Uganda, Frontiers in Science, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 12-19. doi: 10.5923/j.fs.20140401.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Smallholder dairy farming system constitutes an important source of livelihoods to the majority of mixed crop-livestock farmers involved in agricultural production in Uganda [1]. While, smallholder dairy farmers make a shift towards market-oriented dairy production, they are faced with persistent challenges of low productivity, coupled with limited labour inputs. This practice has condemned smallholder dairy farmers to subsistence production, resulting to low income, low saving and low investment in the dairy sector, triggering vicious cycle of low inputs, low productivity, low technology applications and environmental degradation, which translate into abject poverty [2]. Uganda’s slow growth in the dairy sector is evidenced by declining production yields lower than the potential production estimated growth of about 70% [3] considering that over 85% of dairy farmers are smallholders. The annual Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of agriculture in year 2012/13 was 1.4% and unstable [4], yet population growth is estimated at 3.2 percent per annum and appears to be on the rise [5]. Therefore, it was important, to understand production characteristics of smallholder dairy farming so as to identify their opportunities and strength, and build on their threats and weakness to benchmark future research processes aimed at extracting famers out of abject poverty and extreme hunger.Dairy production has become increasingly intensive to cope with nutritional needs of increasing human population and declining per capita land holding [6]. This has led to intensification of smallholder dairy farming adopting stall-feeding (also known as “cut and carry”) where one to three heads of cattle are fed indoors instead of in-situ grazing [7]. Smallholder dairy farming has become an important source of milk and has created employment for many resource poor households in Uganda [1], partly due to Uganda's national development plan (NDP) policy whose objective is to eradicate poverty through agricultural transformation [3]. Smallholder dairy farming, usually 1 or 2 heads of cattle, has the highest economic returns compared to other cattle management systems [3]. However, low productive performance reduces its profitability [8]. For example, annual average milk yield per cow per lactation year of 305 days in developed countries is in excess of 8000 kg, while on smallholder dairy farm in Uganda it is less than 2000 kg per cow per lactation year [9]. Such low milk productivity is to a large extent a result of feed scarcity that leads to poor nutrition [8]. Smallholder dairy farming is based on stall feeding as major feeding system, because of its efficiency compared to other feeding systems. However, little information is currently available on production characteristics of smallholder dairy farming in Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone (LVZ), in Uganda. Moreover, production characteristics of smallholder dairy farming influence decisions on technology dissemination for future profitability. Since interaction between production and management revolve mostly around the supply of nutrients and energy through dairy feeds, there is need to characterize smallholder dairy farming system in order to predict their performance and benchmark strategic research innovations to address declining smallholder dairy farmer productivity. However, although several studies based on farm characteristics have been conducted among smallholder dairy farmers; little success has been achieved in extricating them out of the persistent extreme hunger and poverty. The objective of this study was to characterize smallholder dairy farming system from farmers’ point of view so that together with scientists the farmers inform the process of identifying various intervening strategies to develop dynamic optimization interventions aimed at increasing milk productivity based on the most pressing challenges and un exploited resource endowments peculiar to each region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

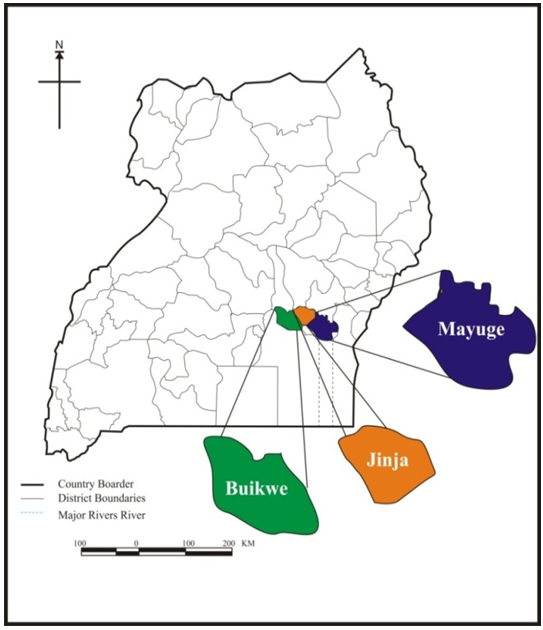

- Three districts namely Buikwe (0°18’4.32 N and 33°3’6.63 E), Jinja (0°25’28 N and 33°12’15 E) and Mayuge (0°27’35 N and 33°28’49 E) (Figure 1) were purposively selected for the study. The mean daily temperature ranged between 16-28℃, 18-28℃ and 17- 27℃ for Buikwe, Jinja and Mayuge Districts, respectively. The mean annual rainfall ranged between 1279 to 1544 mm, 1200 to 1500 mm and 1100 to 1500 mm for Jinja, Mayuge and Buikwe, respectively. The three districts are located in Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone (LVZ).

| Figure 1. Map of Uganda showing the study locations of Buikwe, Jinja and Mayuge districts |

2.2. Sampling Procedure, Sample Size, Data Collection and Analysis

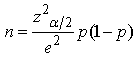

- Three districts were purposively selected based on the reported intensity of smallholder dairy farms [3]. A three stage stratified multi-stage cluster sampling procedure was done; the first stage involved considering each of the districts as a homogenous group stratum (Domain of analysis). The second stage involved simple random sampling of three sub-counties per district in consultations with the district extension staff and sub-county extension officers. All the smallholder dairy farmers in the sampled sub-county were considered. Selection of households was also by simple random sampling. Sample size was estimated using the following formula [10]

Where n = Sample size, Zα/2= Confidence interval at 95% (Standard value of 1.96) p = 10% of proportion of smallholder dairy farmers in LVZ, Uganda [5] and e = desired levels of precision at 5%. The chosen sample required 14 respondents in each study site, which was a sub-county, totalling to 42 respondents per district. Altogether, 81 men and 45 women participated in the three districts. Data was obtained using structured and semi- structured questionnaires administered by way of one-on-one direct interviews. Focus group discussions (one per sub-county) were also held to corroborate the information gathered in direct interviews. The questionnaires and focus group discussions were intended to capture information on production characteristics on smallholder dairy farms. The data captured was on household demographics, highest education level of household head, major sources of income into household, herd size, general challenges, available feed resources, labour activities and challenges in milk marketing. In order to establish differences among farmers’ ranking of the different variables, farmers’ responses were pooled and subjected to nonparametric statistics analysis (Kruskal – Wallis one-way analysis of variance) [11]. Variables were ranked by farmers using a scale of 1 to 5 with five being the most important factor. The computed mean of ranks were compared using multiple pair-wise comparisons to establish if there were significant differences in variables [12]. XLSTAT [11] was used to generate summary statistics (frequencies, percentages and means) for the variables and later tabulated. Means of ranks of variables were analysed using Chi square and were considered different at P<0.05.

Where n = Sample size, Zα/2= Confidence interval at 95% (Standard value of 1.96) p = 10% of proportion of smallholder dairy farmers in LVZ, Uganda [5] and e = desired levels of precision at 5%. The chosen sample required 14 respondents in each study site, which was a sub-county, totalling to 42 respondents per district. Altogether, 81 men and 45 women participated in the three districts. Data was obtained using structured and semi- structured questionnaires administered by way of one-on-one direct interviews. Focus group discussions (one per sub-county) were also held to corroborate the information gathered in direct interviews. The questionnaires and focus group discussions were intended to capture information on production characteristics on smallholder dairy farms. The data captured was on household demographics, highest education level of household head, major sources of income into household, herd size, general challenges, available feed resources, labour activities and challenges in milk marketing. In order to establish differences among farmers’ ranking of the different variables, farmers’ responses were pooled and subjected to nonparametric statistics analysis (Kruskal – Wallis one-way analysis of variance) [11]. Variables were ranked by farmers using a scale of 1 to 5 with five being the most important factor. The computed mean of ranks were compared using multiple pair-wise comparisons to establish if there were significant differences in variables [12]. XLSTAT [11] was used to generate summary statistics (frequencies, percentages and means) for the variables and later tabulated. Means of ranks of variables were analysed using Chi square and were considered different at P<0.05.3. Results

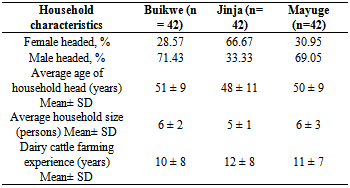

3.1. Household Demographics

- Household demographics led into understanding of farming decisions, choice and levels of adoption of agricultural technologies in smallholder dairy farming system [13]. Across the household stratification, the majority of smallholder households in Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone (LVZ) were headed by males (Table 1). Household head is that person in the household who takes the overall social and economic decisions, assigns responsibilities, allocate resources and shoulders all the challenges and threats in the household. Besides, a household is defined as a group of persons who live and have meals together [5].

|

3.2. Education Level

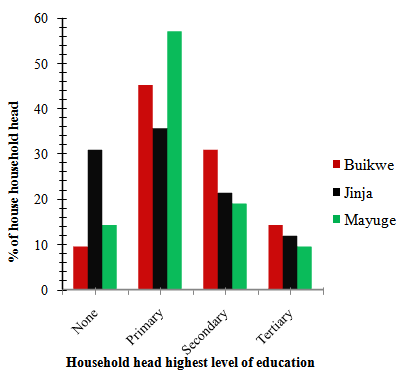

- The education level of the household heads in smallholder dairy farming system was relatively high in the study districts with majority having attained primary seven and above (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. The highest level of education of the household heads in the smallholder dairy farming system in Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone, Uganda |

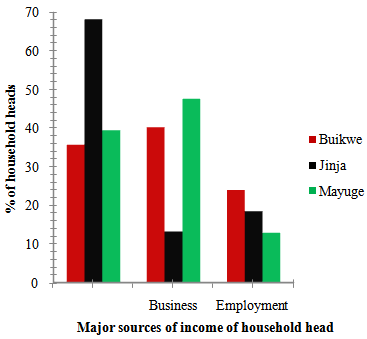

3.3. Source of Income of Household Heads

- There was variation in major sources of income of household heads between the three districts. The highest percentages of household heads in Jinja district were full time farmers (68.24%) compared with Buikwe (35.73%) and Mayuge (45%) where over 52.9% of household’s heads were engaged in other businesses and employment apart from farming as indicated as in Figure 3.

| Figure 3. The major sources of income of household heads of smallholder dairy farmers in Lake Victoria Agro-ecological Zone, Uganda |

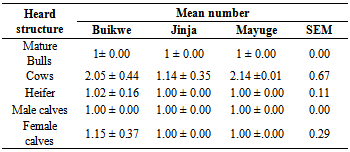

3.4. Herd Size and Structure on Smallholder Dairy Farms

- Smallholder dairy households in the districts of Buikwe had a relatively larger dairy herd size (4.29 ± 0.86) compared to Jinja and Mayuge districts with herd size (3.12 ± 1.45 and 2.43 ± 1.12), respectively (Table 2). Cows constituted the highest proportion (48.3%) of the herd in Buikwe followed by heifers (22.34%). Smallholder dairy farmers in LVZ kept bulls for breeding purposes because artificial insemination services were reported to be unreliable.

|

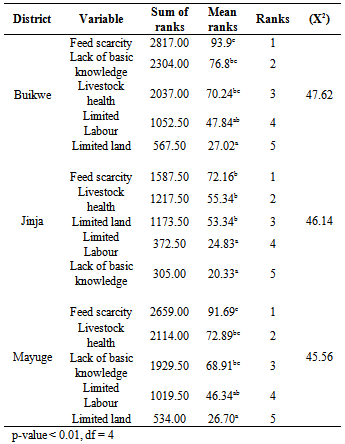

3.5. Farmers Ranking on Challenges in Smallholder Dairy Farming System

- The farmers’ ranking of the challenges facing smallholder dairy farming system in LVZ is presented in Table 3. Chi square analysis showed that mean ranks of challenges faced within smallholder dairy farming system significantly varied (p<0.0001) in all the districts. Feed scarcity which was highly pronounced during the dry season invariably topped the challenge rankand it was unanimously ranked as the major challenge in all the three districts by farmers as one of the biggest challenge to productivity in smallholder dairy farming system in LVZ, Uganda.

|

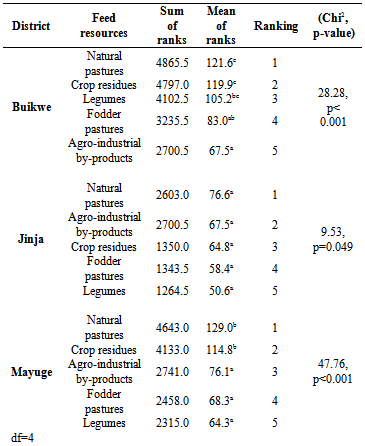

3.6. Farmers Ranking on Feed Resource Utilization in Smallholder Dairy Farming System

- Chi-square test showed that there was a significant difference (p<0.001, df = 4) among farmers’ ranking on availability of different feed resources in LVZ. The significant differences in farmers’ ranking on levels of availability of feed resources were maintained among the districts (Table 4).

|

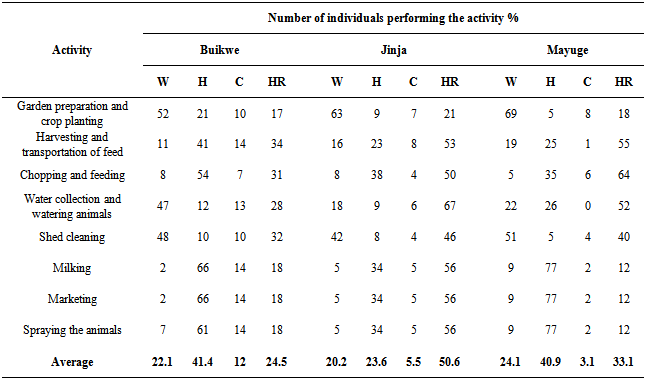

3.7. Availability of Labour in Smallholder Dairy Farming System

- Major activities performed in the smallholder dairy cattle farming system in LVZ, Uganda, are shown in Table 5. Most of these are performed daily, indicating that smallholder dairy farming is a labour intensive system. There were no distinct age and sex division of labour, but all gender contributed to all farm activities. However, there were disparity in level of labour contribution between men, women and children for activities related to dairy production. In Buikwe and Mayuge on average, men contributed more labour (41.4 and 40.9%, respectively) in the dairy unit than women (22.1 and 24.1%, respectively). Women’s labour activities were highest in shade cleaning than in any other activity while men’s highest labour activities were in chopping and feeding, milking, marketing of milk and spraying against ticks as indicated in Table 5.

|

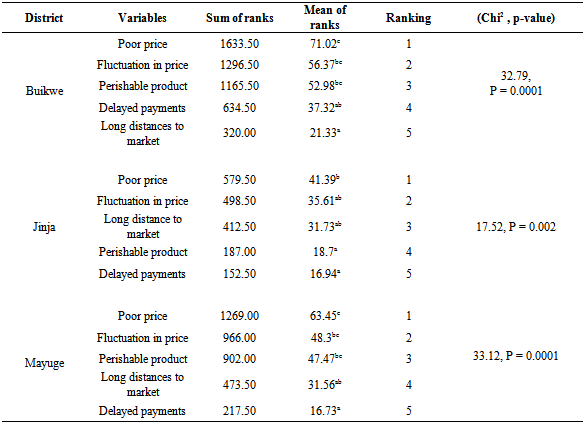

3.8. Challenges of Milk Marketing in Smallholder Dairy Farming System

- Chi-square test showed how farmers ranked the challenges associated with raw milk marketing in LVZ in the three districts (Table 6). Poor price was the top most challenge identified by the farmers while unstable price of milk was ranked the second major challenge in all the districts all the districts (Table 6). Limited value addition to the highly perishable milk rendered it rather difficult to fetch reasonable prices despite its high local demand at the farms. Instability in milk price proves the high dependence on natural pastures as source of nutrients, which was dependent on weather situation. Generally, during the wet season, there was improved feed availability leading to increased milk output per household that would result into reduced milk prices, while in the dry season milk output was low resulting in increased prices.

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Households

- The possible explanation of proportion of higher female households heads in Jinja district than in other districts of Buikwe, Mayuge was because, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO), “Heifer Project International”, which operated in the region prior to the study targeted women for economic empowerment and those who had been widowed by HIV/AIDS for receipt of in calf heifers, hence a relatively high proportion of women household heads who owned dairy cattle. This is supported by the fact that the average age of household head in Jinja was lower compared to Buikwe and Mayuge. Average household members in Jinja were also lower than those in Buikwe and Mayuge respectively. Typically, household members comprised of husband, wife and children. The size of household members could influence labour availability in dairy farming with Jinja having less labour available to perform dairy activities and relied most on hired labour. Availability of labour in any production system has a significant influence on productivity and since smallholder dairy farming system is labour intensive [14] labour costs and availability had fundamental influence on productivity. Buikwe district had more farmers who had finished tertiary institutions of learning, suggesting that adoption levels in Buikwe for a new innovation can be high compared to other districts. [15] noted that raising in education levels is proportional to level of adoption of agricultural technologies which is consistent with the general belief that adoption levels are positively correlated with levels of education. This is possibly because education influences the ability of farmers to interpret the technical recommendations that may require some level of education. Furthermore, [16] noted that literate farmers can comprehend the benefits from extension information and they are aware of the consequences of the prevailing challenges if they are not addressed in time. Majority of the farmers in Buikwe and Mayuge had other main sources of income, while smallholder dairy farmers in Jinja relied on dairy farming as their main source of income. This is consistent with [13] who made similar observation where high number of female-headed households in Masaka district in Uganda, who received animals from NGO (send a cow), had no other alternatives form of employment and household income. However, smallholder dairy farming in LVZ seems to be unstable venture due to low investment levels unreliable inputs and lack of infrastructural development such as milk collection centers and coolers to preserve milk which is not immediately consumed. Thus farmers seek other alternative livelihood complimentary means for their livelihoods that sometimes become competitive, deny smallholder dairy farming an opportunity for further knowledge and capital investment.

4.2. Challenges in Smallholder Dairy Farming System

- While increased animal productivity has been identified as one of the options for increasing incomes, household nutrition and livelihood of the rural households [3] feed scarcity was unanimously identified by the farmers as one of the biggest challenge to increased milk productivity in LVZ. The consequence of feed scarcity to smallholder dairy farming system is poor milk yield, distortion of the estrus cycles, poor body condition and long calving intervals [16]. Farmers therefore miss opportunities on proceeds from milk sales and offspring as a result long calving interval [6]. The generally high cost of commercial supplementary feeds irrespective of seasons in LVZ, despite the abundance of agro-industrial by-products points to limited investment of both knowledge and capital in value addition. This is in agreement with earlier observation by [9], who observed that low milk yield in Uganda is attributed to poor feeding methods resulting from not meeting the right nutritional requirement of dairy cattle. Similarly, limited value addition to highly perishable milk renders it rather difficult to fetch reasonable prices despite its local demand right at the farm. These results are consistent with earlier findings [14] which indicated that poor milk price is a major challenge to increased dairy productivity in peri-urban areas of East and Central Africa.

4.3. Labour Activities in Smallholder Dairy Farming

- Most activities were performed daily, implying that dairy farming is a labour intensive enterprise. There were no distinct age and sex division of labour, but all gender contributed to smallholder dairy activities. However, there were disparities in level of labour contribution between men, women and children. In Buikwe and Mayuge districts, on average, men contributed more labour in the dairy unit than women, but in Jinja, men contributed marginally more labour than women. Women contributed labour highly in shed cleaning than in any other activity while men contributed highest in milking, marketing milk and spraying against ticks. Possibly, cultural inclinations in majorly patriarchal societies in the study area where men are seen as household bread winners explains why men were responsible for those activities involving cash transactions in the dairy enterprise. Similarly, all decision concerning labour activities of the enterprise were unilaterally made by the heads of households the majority of whom were men. The contribution of children to running of dairy unit was insignificant, less than 7% on average of total labour activities. Notably, children did not participate in cutting forages, feeding and watering of the animals. The low contribution of children was primarily because they attended school during week days and they were only available during week-ends and holidays. Nonetheless, the family labour was not sufficient to run the dairy unit and significant labour was sourced from outside particularly in Jinja. In Jinja, overall hired labour contributed more than half of the total labour required in running of the dairy enterprises. This implies that external labour is important for the success of dairy farming in the LVZ given the low levels of mechanization. This scenario was also reported by [14] who found out that hired employees contributed about 50% of the entire labour requirement of the dairy unit in the rural areas of semi-arid Kenya.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The conclusions drawn from this study are that lack of knowledge to make timely decisions on available feed resources, limited value addition to highly perishable milk and lack of basic equipments to reduce on hard work are major outstanding challenges pulling down dairy productivity. The efficiency of production and marketing of milk should be improved in order to enhance smallholder dairy production in LVZ, Uganda. Therefore milk productivity can be enhanced through appropriate engagement with the farmer to generate sustainable option to improve nutrient supply throughout the year. Highly appreciated and utilized crop residues and agro-industrial by-products should be identified, limitation to utilization evaluated and supplementary dairy cattle ration based on highly abundant and agro-industrial by-product and crop residue be formulated. Appropriate on-farm feed conservation practices that include biological processing of highly fibrous and lignified crop residues, hay and silage making be promoted on farm. Furthermore, it is necessary to conduct on-farm strategic studies in LVZ, Uganda to upgrade and enhance utilization of crop residues and agro-industrial by-products identified by this study as alternative dairy cattle feeding strategy to meet nutrient requirement during the dry seasons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are grateful to World Bank, East African Agricultural Productivity Project (EAAPP) Uganda for funding this study. We are also thankful to the Director National Livestock Resources Research Institute for facilitating the smooth implementation of the project activities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML