-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Frontiers in Science

p-ISSN: 2166-6083 e-ISSN: 2166-6113

2012; 2(3): 41-46

doi: 10.5923/j.fs.20120203.05

Community Forestry in Nepal:A Scenario of Exclusiveness and its Implications

Dharam Raj Uprety1, Anup Gurung2, Rajesh Bista3, Rahul Karki3, Kamal Bhandari3

1Multi-stakeholder Forestry Programme, Services Support Unit, Kathmandu, Nepal

2Department of Biological Environment, Kangwon National University, Hyoja-dong, Gangwon-do, Chuncheon-si, 200-701, South Korea

3ForestAction, Kathmandu, Nepal

Correspondence to: Anup Gurung, Department of Biological Environment, Kangwon National University, Hyoja-dong, Gangwon-do, Chuncheon-si, 200-701, South Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Nepal’s community forestry program was specifically adopted to address local livelihoods and abate environmental degradation with due consideration of local-specific conservation and development requirements. Although the program has improved forest condition and livelihoods in many cases, it has several limitations and shortcomings particularly in the context of inclusive forest governance. This paper examines the roles and responsibilities of poor, disadvantaged women, Dalits and socially excluded groups in the community forestry process and the way how they are excluded at the time of benefit-sharing and in decision-making. The study is based on three years (2008-2011) long action and learning research in 58 community forest users groups from three eco-zone of Nepal. The study revealed that more attention needs to be paid in making forest user groups more equitable, inclusive and pro-poor in practice. The poor, Dalits, and socially excluded groups are often deprived from their basic rights on accessing of common pool resources, and are often excluded in decision-making system. The notable challenges related to the community forestry in the studied districts include elite domination, inability to provide significant contribution to livelihoods, persistence of social disparity, and low information flow to the poor and marginalized groups.

Keywords: Community forestry, Equity, Exclusion, Governance, Marginalized

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In Nepal, community forestry (CF) program was specifically formulated with the objectives of meeting the subsistence forestry needs of the local people and abate environmental degradation by transferring user rights of forest resources to the local users[1-3]. Local users first formed a local institute as community forest users group (CFUG), and then apply for obtaining a patch of government owned forest as CF[4]. Number of such CFs are now reached more than 18,000[5] because of its successful management history since handed over to local community.Hence, Nepal’s CF is widely known as a successful example of progressive legislation and policies in the decentralization of common pool resources (CPRs) simultaneously meeting the local forest product needs and enhancing biodiversity conservation[2]. At present, Nepal's CF is heralded as an appropriate instrument to help accomplish the national sustainable development strategy by reducing poverty through the efficient use and management of forestresources[1,6,7]. At present approximately 30% (1.3 million ha) of national forestlands have been handed over to more than 17,600 CFUGs1 involving more than 1.8 million households[8].The CF program has met with some notable successes in terms of enhancing flow of forest products, improving livelihoods opportunities for forest dependent people, strengthening social capital, and improving the biophysical condition of forest[9-13]. Because of these successes, Nepal’s CF has moved beyond to its original goal of fulfilling basic forest needs of the people including, and it is now a pioneer in terms of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)[3,6,14,15].Despite the multiple functions of CF including social, economic and environmental benefits, it continues to face organizational, structural, and societal challenges[1,6,7]. Many studies have reported that social inequity and exclusion of the poor, women, and marginalized groups from gaining access to and control over CF resources, and benefits-sharing are the common problems in CF[2,15-18]. Although Nepal’s CF is increasingly recognized in delivering good governance through the CFUGs including transparency, accountability, benefits-sharing, decision-making, fairness, and inclusiveness[6,9,19] the CF policy itself is exclusionary[20] in terms of bringing voices of poor and disadvantaged section of society. The policy does not recognize social aspect of managing local forest resources rather it largely focuses on scientific forestry ideology in the terms and conditions of partnerships[1,3,20].Recent studies shows that most of the CFs are dominated by wealthier and upper caste group particularly those belonging to Brahmin, Chhetri and other privileged groups in both decision-making and benefit distribution, and therefore, the opportunity for socially marginalized people such as poor, women, and Dalits2 to be involved in CF program are not adequately taken into consideration[2,15,17,18,21]. Due to inequitable distribution of benefits-sharing, combined with unequal social structure and uneven sense of ownership, the livelihoods of the poor have not improved as expected[1,17].There are many factors that hindered inclusive CF in Nepal, and of them caste culture, social hierarchy, economic status of an individual, educational attainment are mainly responsible for the exclusion of poor and marginalized groups in the CF process[1,4,11,22]. Moreover, socioeconomic disparity among users and their dependency on CPRs has become a matter of concern, when a responsibility of allocating CPRs is delegated to local communities[7]. In order to achieve the dual goals of poverty reduction and environmental conservation through the sustainable forest management, the poor and marginalized groups, who depend more on forest resources for their livelihoods, have to be included in the CF program[12,19], particularly in the decision-making level. Social exclusion can bring disputes among CFUG members, which can disrupt social harmony and collective action[4]. This paper, therefore, intends to explore the critical social asymmetric in a scenario of exclusiveness of poor, disadvantaged women and Dalits, and its implications in CF process.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Study Site and Data Collection

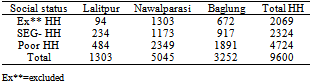

- The survey was conducted in three districts: Lalitpur, Baglung, and Nawalparasi, covering the three geographical regions of Nepal, namely Mid-hill, High-hill and Terai. In order to evaluate trend of CF under the CFUGs, with due consideration of CF contributing to sustainable livelihoods and its management governance, three clusters was selected from each district: Lamatar cluster of Lalitpur district, Kusmisera cluster of Baglung district, and Nawalpur cluster of Nawalparasi district. While choosing the clusters, it was considered that each cluster must have at least one CFUG which applied governance reform and collaborative learning. Table 1 depicts the total CFUGs along with total users in the studied sites.

|

3. Results

3.1. Status of Poor and Excluded Households in the CF

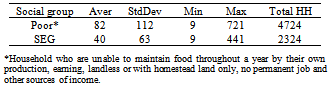

- The research findings revealed that the existing CFs have failed to provide significant contribution to livelihoods, particularly for poor and marginalized communities in the studied districts. There was persistence of social disparity among FUGs, and most of the CFUGs are dominated by elite group (Brahmin and Chhetri). Table 3 shows the total number of poor and SEGs in 58 CFUGs of the three districts. Poor and marginalized groups, particularly Dalits had less access to forest resources, and often excluded from decision-making system of CF.

|

|

|

3.2. Participation in Decision-making Process

- An investigation in the participation of different social groups (poor, women, SEGs, and marginalized groups) in the FUGs meeting, forest products distribution and other activities of CF revealed that the participation is not uniform across poor, Dalits, and marginalized groups of people (Table 6). In Baglung and Lalitpur, most of the excluded households were poor and Dalits, who totally rely on the surrounding forests for their livelihoods even before the formation of CFUG. These marginalized groups of people were excluded intentionally during the formation of CFUG with the reasons of the destroyers of the forests. In recent years, these groups have shown interest to be included in the CFUGs; however, their interests and voices were not listened by the Use Group Committee (UGC).In Baglung, majority of the excluded households were Dalits. Some of them have applied for the membership but the response of UGC and elite members of the CFUG remained negative for them. Interestingly it was found that SEGs are still unaware about the CFUG process, and none of them have applied for the membership due to rigid caste and class domination in the society. Although higher proportions of poor households were excluded in Nawalparasi, the situation is different in Baglung and Lalitpur. It was found that there is caste based society in Baglung and Lalitpur, and therefore, Dalit were excluded but the educated people of socially excluded groups have been able to elect in UGC in some of the CFUGs.In general, participation of poor, Dalits, women, and Janajatis7 are much lower as compared to elite groups (Brahmin and Chhetri) on meeting, minute, and other activities related to CF. In most of the cases, Dalits, women, and SEGs are not informed about the CFUG meeting that make rules governing the development, maintenance, and utilization of forest products within the CFUG. The research findings revealed that the roles and responsibilities of women in the CF is not taken into consideration and often neglected. A huge number of users still lack information about CF pertaining to their rights to participate in decision-making system and benefits-sharing.

|

3.3. Knowledge of Fundamental and Legal Rights Among the Socially Excluded Groups

- In most of the CFUGs, UGC is formed by the elite group, and are well-known about their fundamental and legal rights as well as their duties in the CF. In some clusters, educated members from Janajatis and Dalits are also appointed in UGC and are aware about the property rights and their duties. However, UGC formed by the illiterate members particularly from Janajatis and Dalits are found to be selected in the UGC only for formality sake, and are unaware about their basic rights. Moreover, important decisions are taken and applied by the elite group in such communities. For example, there are some poor, women, and Dalits in the CFUGs but don’t allow to participate in decision making-process in CFUGs. These people are selected only for forest protection rather than equitable distribution of benefits and access to forest products. In some CFUGs, SEGs and Dalits are allowed to collect firewood and fodder from time to time; however, they are never made them feel that they are part of the CF itself and have equal rights as elite group posses.In Nawalparasi, the status of socially excluded group was better in terms of having access to forest products and their rights in the CFUGs as compared to Baglung and Lalitpur. According to the household survey and FGD, SEGs in Sundari CFUG were found to be aware about their rights and duties. The reason behind this fact was that Sundari CFUG has been allocating NRs 60,000/year for construction of houses and providing to the poor families in the community. Similarly, in Dhuseri, Jyoti-kunja, Amar, Mukundasen, and Sankhadev-hasaura CFUGs, the higher amount of income earned from CF was invested for CF management as well as for community development activities. These provisions encouraged poor and SEGs to take part in meeting and seminar that are designed to promote knowledge about fundamental and legal rights of the CFs.

3.4. Election of Executive Committee and Distribution of Fund

- According to the household respondents, election for executive committee members in CFUGs was recently established phenomenon. Although election is considered as one of the important instrument of democracy and good governance for giving equal opportunity to the communities irrespective of their social status, only 8 CFUGs out of 58 CFUGs elected their executive members through election (Table 7). In most of the cases, power domination and seniority played important role in choosing executive committee in the CFUGs. Apart from these, friendly nature, previous record, and availability of time are also considered as important criteria for electing executive members.

|

|

4. Discussion

- Nepal’s CF program is recognized as pioneer in being more responsible, accountable, transparent, decentralization and devolution of power and authority, pursuant of participatory decision-making, equitable representation and user balance[13,17,24,25]. Several case studies revealed that the CF program has been successful in restoring degraded land improving the forest conditions[1,10,13,15,16,21,26]. Apart from environmental services, conservation of biological diversity is another important dimension of environmental sustainability of the CF[1]. Improved forest conditions maintains the forest sustainability thereby providing forest products to the local people which in turn is expected to improve their livelihoods[1,12,16]. However, the research findings indicated that the ability of CF to improve the livelihood of the poor and marginalized groups remained questionable.The research finding revealed that the interest and expectation of the poor and SEGs to be involved in CF has not been taken into consideration by the elite group. It was observed that local elites are benefiting most because they hold the powerful positions in the executive committees and can manipulate the decisions in their own favour, ignoring the agendas of the dalits, SEGs, poor and marginalized people in the society. In most of the studied CFUGs, executive members were selected without having election. Moreover, the constitution of the CFUGs do not account for the importance of heterogeneity in terms of caste, class (poor, rich, medium), and culture both in benefit-sharing and forming executive committees. Thus, due to lack of concrete provision, the decision-making platform is dominated by the higher caste and wealthier people.Moreover, the research findings unveiled that the present protection oriented approach of forest management adopted by the FUGs is unable to improve the livelihoods of the poor mainly due to low income and limited supply of forest products from the CFs. Most of the studied CFs were unable to meet the users’ needs, and also the products extraction and distribution systems are generally against the interest and needs of the poor and marginalized groups. There is a limited flow of information to the poor, Dalits, and SEGs particularly about income and expenses of the CFUG. Most of the poor users remained unaware about the total income and expenditure of the CFUGs as well as sources of fund. Since key positions were dominated by the elite and wealthier people, the decisions pertaining to the CFUGs are likely to go in favour of non-poor. The research findings indicated the necessity of revising the present protection-oriented approach of forest management thereby focusing on recognition of the roles and responsibilities of poor, Dalits, disadvantaged women, and SEGs in CBNRM. Therefore, Nepal’s CF program needs to engage directly with social change, bringing the poor and Dalits at the forefront of decision-making and need to mainstreaming them in developmental programs.

5. Conclusions

- Nepal’s CF has faced mounting challenges, limitations, and shortcoming, specifically in implementation of development programmes. The findings of this study showed that Dalits, SEGs, poor and marginalized groups are benefitting less, and often excluded from the access of CF. Poor, Dalits, and SEGs were mainly excluded due to socio-cultural, economic and institutional factors at the community level. Moreover, the issue of access to the CPRs is associated with power. Due to inequitable benefit-sharing and power domination, the livelihood of the forest dependent people couldn’t improve as expected. The research findings revealed that more attention needs to be paid in making FUGs more equitable, inclusive and pro-poor in practice. Another notable challenge in Nepal’s CF is to make collective decision-making more transparent and participatory as current CFUGs are dominated by elite capture. Therefore, without understanding the context and properly addressing issue beyond the forestry, the national campaign of poverty alleviation through the sustainable utilization of forest products cannot be achieved.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This manuscript is a part of the project, Reducing Poverty through Innovation System in Forestry (RPISF), hosted by ForestAction Nepal and funded by the Research into Use (RIU) program of the Department for International Development (DFID), United Kingdom. The authors would like to thank all individuals, communities, organizations, and institutions for making the study successful.

Notes

- 1. A group of people who regularly uses a particular forest for various purposes and organize themselves to protect, manage, and utilize by forming a local group.2. Dalits are defined as historically and socially discriminated so-called “lower caste” or untouchable” according to Hindu caste division system. Dalits are a mixed population of numerous caste groups such as Kami (blacksmiths), Damai (tailors), Sarki (shoemakers), and so on.3. Socially excluded groups are those who are far from the mainstream of community forest and are unaware of the community forest process as well as benefits due to their socio-cultural and economic conditions.4. On the other hand, socially excluded groups represent those people who might have been included as the members of the CFUG but are prevented from being part of the mainstream of the community forestry due to their socio-cultural and economic conditions. These people can be known as low caste people, women, poor, and marginalized people.5. In community forestry, excluded households denote to the households who are not the members of community forestry and thus, restricted from forest management and use although they are interested to be part of it.6. 1US$=85 NRs as of May 23,2012.7. Janajatis are generally non-Hindus with their distinct identities regarding religious beliefs, social practices and cultural values. Throughout the history of Nepal, Janajatis have been marginalized in terms of language, culture, political and economic opportunities. Gurungs, Sherpas, Thakalis, Tamangs, Rais, Limbu, Magar, etc.

References

| [1] | Gautam, A.P., (2009) Equity and livelihoods in Nepal's community forestry. Int. J. Soc. Forestry, 2, 101-122. |

| [2] | Gentle, P., Acharya, K.P. and Dahal G.R., (2007) Advocacy campaign to improve governance in community forestry: a case from Western Nepal. J. Forest Livelihood, 6, 59-69. |

| [3] | Kanel, K.R. and Dahal G.R., (2008) Community forestry policy and its economic implications: an experience from Nepal. Int. J. Soc. Forestry, 1, 50-60. |

| [4] | Uprety, D., (2007) Community forestry, rural livelihoods and conflict: A case study of community forest users' groups in Nepal. Guthmann-Peterson buch verlag, Vienna, Austria. |

| [5] | DOF, (2010) Community forestry user groups database. Community Forestry Division, Department of Forest (DFO), Kathmandu, Nepal. |

| [6] | Giri, K. and Ojha H., (2010) Enhancing livelihoods from community forestry in Nepal: can technobureaucratic behaviour allow innovation systems to work? 9th European IFSA Symposium, 4-7 July 2010, Vienna, Austria. |

| [7] | Sapkota, I.P. and Oden, P.C., (2008) Household characteristics and depedency on community forests in Terai of Nepal. Int. J. Soc. Forestry, 1, 123-144. |

| [8] | MOF, (2011) Economic Survey: Fiscal Year 2010/11. Ministry of Finance (MOF), Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal. |

| [9] | Acharya, K.P., (2002) Twenty-four years of community forestry in Nepal. Int. Forestry Rev., 4, 149-156. |

| [10] | Adhikari, B., (2005) Poverty, property rights and collective action: Understanding the distributive aspects of common property resource management. Environ. Dev. Econ., 10, 7-31. |

| [11] | Gautam, A.P., Shivakoti, G.P. and Webb, E.L., (2004) A review of forest policies, institutions, and changes in the resource condition in Nepal. Int. Forestry Rev., 6, 136-148. |

| [12] | Ojha, H.R., Cameron, J. and Kumar, C., (2009) Deliberation or symbolic violence? The governance of community forestry in Nepal. Forest Policy Econ., 11, 365-374. |

| [13] | Dev, O.P., Yadav, N.P., Springate-Baginski, O. and Soussan, J.G., (2003) Impacts of community forestry on livleihoods in the middle hills of Nepal. J. Forest Livelihood, 3, 64-77. |

| [14] | Kanel, K.R. and Niraula D.R., (2004) can rural livelihood be improved in Nepal through community forestry? Banko Janakari, 14, 19-26. |

| [15] | Richards, M., Maharjan, M. and Kanel, K.R., (2003) Economics, poverty and transparency: measuring equity in forest user groups. J. Forest Livelihood, 3, 91-104. |

| [16] | Adhikari, B., Williams, F. and Lovett, J.C., (2007) Local benefits from community forests in the middle hills of Nepal. Forest Policy Econ., 9, 464-478. |

| [17] | Pokharel, B.K. and Nurse, M., (2004) Forests and people's livelihood: benefiting the poor from community forestry. J. Forest Livelihood, 4, 19-29. |

| [18] | Graner, E., (1997) The political ecology of community forestry in Nepal. Verlag fur Entwickungspolitik, Saarbrucken. |

| [19] | Wagley, M. and Ojha, H., (2002) Analyzing participatory trends in Nepal's community forestry. Policy Trend, 122-142, IGES, Japan. |

| [20] | Khadka, K.R., (2009) Why does exclusion continue? Aid, knowledge and power in Nepal's community forestry policy process. Maastricht, Shaker Publishing, The Netherlands. |

| [21] | Adhikari, B., Di Falco, S. and Lovett, J.C., (2004) Household characteristics and forest dependency: evidence from common property forest management in Nepal. Ecolog. Econ., 48, 245-257. |

| [22] | Gautam, K.H., (2006) Forestry, politicians and power--perspectives from Nepal's forest policy. Forest Policy Econ., 8, 175-182. |

| [23] | Bohra, P. and Massey, D.S., (2009) Processess of internal and internationalo migration from Chitwan, Nepal. Int. Migration Rev., 43, 621-651. |

| [24] | Springate-Baginski, O., Soussan, J.G., Dev, O.P., Yadav, N.P. and Kiff, E., (1999) Community forestry in Nepal: impacts on common property resource management. School of Environment and Development, Series No. 3, University of Leeds, UK. |

| [25] | Hausler, S., (1993) Community forestry: a critical assessment. The Ecologist, 23, 84-90. |

| [26] | Springate-Baginski, O., Yadav, N.P., Dev, O.P. and Soussan, J.G., (2003) Community forest management in the middle hills of Nepal: the challenges context. Forest and Livelihood, 3, 5-20. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML