-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2025; 15(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20251501.01

Received: Dec. 12, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 15, 2025; Published: Jan. 24, 2025

The Influence of Human Resource Factors on Access to Mental Health Services in Primary Care Facilities in Kiambu and Makueni Counties, Kenya

Milcah Ndinda Musyoki 1, Kezia Njoroge 2, Caroline Kawila Kyalo 1

1Department of Health Systems Management, Kenya Methodist University, Kenya

2Department of Public and Allied Health, Liverpool John Moores University

Correspondence to: Milcah Ndinda Musyoki , Department of Health Systems Management, Kenya Methodist University, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The incidence of mental health issues in Kenya has increased over the years. Although Kenya has adopted a policy framework to integrate mental health services in primary healthcare facilities, only 29 of the 284 hospitals in level four and above offer mental healthcare services, with Mathari National Referral Hospital serving as Kenya's sole referral for such services. This scenario clearly demonstrates that access to mental health is not fully mainstreamed in primary healthcare facilities. Worse still, the existing service statistics show that Kenyan psychiatry is under-resourced in terms of personnel. This study, therefore, explores the influence of human resource factors on access to mental health services in primary care facilities in Kenya. The study adopted a cross-sectional mixed methods research design. The target group was healthcare providers from Kiambu and Makueni primary healthcare facilities. The Yamane formula was used to calculate the sample size of 179 healthcare facilities as a unit of analysis. Two health practitioners were selected in each health facility, yielding 358 respondents. Respondents were clinical officers and nurses who directly interacted with patients in primary health facilities. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data from staff members in the selected counties. Collected data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression. Results indicated that human resource factors significantly predict access to mental health services in primary care health facilities in Makueni and Kiambu Counties.

Keywords: Mental Health, Primary health care, Primary care facilities, Human resources

Cite this paper: Milcah Ndinda Musyoki , Kezia Njoroge , Caroline Kawila Kyalo , The Influence of Human Resource Factors on Access to Mental Health Services in Primary Care Facilities in Kiambu and Makueni Counties, Kenya, Food and Public Health, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20251501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Mental illness is one of the major global public health issues. Mental illnesses are widespread and seriously damage many regions of the world. According to WHO [1,2], about 450-500 million individuals worldwide suffer from a mental ailment, which can contribute up to 14% of the world's disease burden. In primary health care (PHC) settings, up to 70% of patients with mental health (MH) are followed up. Because of the growing number of mental illnesses, global initiatives have been undertaken to reduce the prevalence of mental illnesses. The initiatives include the creation of the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) guideline for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders and the formulation of the “Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030", which aims to improve mental health by strengthening effective leadership and governance, providing comprehensive, integrated and responsive community-based care, implementing promotion and prevention strategies, and strengthening information systems, evidence and research [3,4]. In Kenya, mental illness is a significant health burden. According to MOH [5], 1% of the general population in Kenya has mental-related illnesses. In 2019, the president of the Republic of Kenya declared mental ill health as a national health emergency [5]. Consequently, national initiatives have been undertaken to address the threat posed by mental illness. These include The Constitution of Kenya 2010, Vision 2030, and the Kenya Health Policy (2014- 2030), which are in line with the global commitments to mental health. The Constitution of Kenya 2010, in article 43. (1) (a) provides that “every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to healthcare services” [5].Whereas mental ill health has been recognized as a national health emergency in Kenya, only 29 of the 284 hospitals in level four and above offer mental healthcare services. Mathari National Referral Hospital is Kenya's sole referral for such services [6]. This scenario demonstrates that access to mental health is not fully mainstreamed in primary healthcare facilities, although MOH [5] recommends that mental health be decentralized to primary healthcare in Kenya.In Kenya, there is a huge treatment gap for people with mental illness. Currently, Kenya has 120 psychiatrists for a population of over 50 million people. Most psychiatrists operate in private practice, meaning their services are unaffordable to most Kenyans. Most psychiatrists in the public sector are situated in Nairobi, leaving a significant gap in service delivery in rural areas. While not all mental illnesses require psychiatric intervention, most do require intervention through psychologists, professional counsellors, and psychotherapists, who are also scarce in rural areas [7]. This study explores the influence of human resource factors on access to mental health services in Kiambu and Makueni Counties, Kenya.

2. Past Studies

- Globally, the treatment of mental illnesses has been hampered by the significant scarcity of psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists, social workers, and psychologists [1]. Most mental health workers tend to be concentrated in urban areas, leaving very few mental health workers in rural areas [8]. Ding to the WHO Mental Health Treatment Gap Action Program (mhGAP), low-income nations, particularly those in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America, are bearing the brunt of the global acute shortage of healthcare personnel. Geographically, there is a considerable gap between what is available in rural and urban areas. About 70% of the Kenyan population lives in rural areas. This inconsistency is also replicated in mental health services [9]. Most private facilities in significant urban centers and referral private hospitals offer specialized psychiatric care. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate the number of specialists involved in delivering care for people with mental issues [5].Poor human resource distribution in Nepal makes it challenging to deliver mental health care. For instance, there are supposedly only 27 psychiatrists in the nation. Because of the unequal geographic distribution of services, only urban areas can access mental health facilities, leaving rural areas without such facilities. Most people with mental health issues choose to see traditional healers [10].In South Africa, little emphasis is placed on mental health. Therefore, patients do not get the attention they require from these facilities. Many nurses lack the knowledge and abilities to recognize and treat mental health disorders, and they frequently have unfavorable views about those who suffer from mental illness. This results in the delivery of services that are often insufficient and subpar [11].

3. Data and Methods

- The study adopted a cross-sectional survey design. The study focused on healthcare practitioners at levels 2, 3, and 4 in Kiambu and Makueni Counties. The Tara Yamane (1973) formula was used to calculate the number of facilities. Consequently, 179 primary healthcare facilities in Kiambu and Makueni counties arrived. Two healthcare professionals were chosen from the selected health facilities using a simple random sampling. Thus, the study sample was 358 healthcare workers. Structured questionnaires were administered to the 358 health workers. A binary logistic regression model was then fitted into the collected data.

4. Results and Discussions

- This section presents the results of the analysis. Human resource factors included Staff training, staff distribution, and staff skills mix.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics on Staff Training

- Figure 1 shows the results of staff training.

| Figure 1. Staff training |

4.2. Descriptive Statistics on Staff Distribution

- Figure 2 presents results on staff distribution in primary healthcare facilities in Kenya.

| Figure 2. Staff distribution |

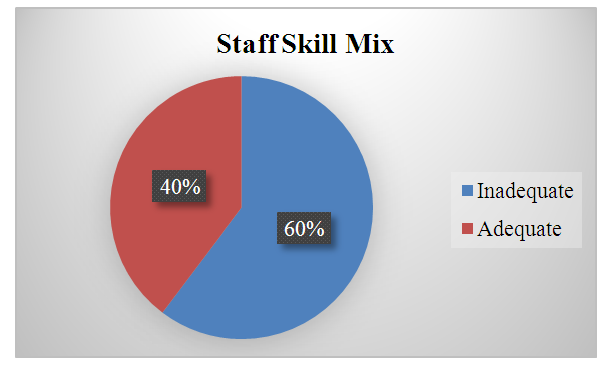

4.3. Descriptive Statistics on Staff Skills mix

- Figure 3 presents descriptive results on staff skills mix in primary health care facilities in Kenya.

| Figure 3. Staff Skill Mix |

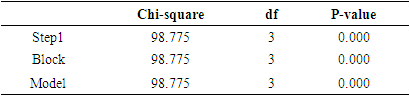

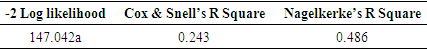

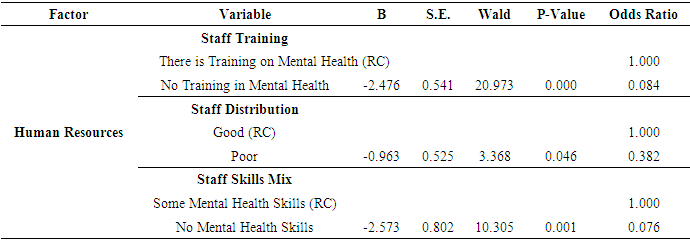

4.4. Regression Results

- To determine the influence of human resource factors on access to mental health services in primary care facilities in Kiambu and Makueni counties, Kenya, binary logistic regression was fitted into the data. Human resource factors included Staff training, distribution, and skill mix. The results are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4.

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions and Implications for Policy

- Based on the results of this study, it is evident that human resource factors play a crucial role in access to mental services in Kiambu and Makueni Counties of Kenya. Staff training, staff distribution, and staff skills mix were significantly associated with increased odds of access to mental health services in primary health care facilities in Makueni and Kiambu counties of the Republic of Kenya. Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are suggested, which are in line with the Mental Health and Wellbeing: Towards Happiness and National Prosperity (2020) taskforce report [5].The Ministry of Health needs to set aside resources for training, recruitment, and deployment of adequate multidisciplinary mental health service providers since staff training was found to influence access to mental health services. Similarly, in conjunction with county governments, the Ministry of Health should ensure the training and recruitment of mental health professionals to shift the gap in human resources per population ratio as envisioned in the 2020 Mental Health Taskforce report [5].

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML