-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2022; 12(2): 48-55

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20221202.02

Received: Jul. 28, 2022; Accepted: Aug. 8, 2022; Published: Aug. 23, 2022

Factors Affecting the Quality Healthcare Accessibility and Delivery for the Elderly in Ghana

Edem Segbefia, Philip Batsa Adotey

School of Management, Jiangsu University, 301 Xuefu Road, Zhenjiang, P.R. China

Correspondence to: Philip Batsa Adotey, School of Management, Jiangsu University, 301 Xuefu Road, Zhenjiang, P.R. China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: This is a study seek to assess the factors affecting quality healthcare delivery and among the aged in Ghana. The study was conducted among three hospitals namely Korle Bu, Accra regional and Cape Coast Teaching Hospital. Method: The study considered a sample size of 397 patients representing 99.25% of respondents from the point of accessing service from the Hospitals through a random sampling method. The Warp PLS statistical software version 7.0 was used to perform SEM. Result: The study revealed that respondents believe that quality healthcare is incomparable irrespective of the cost. Though quality healthcare is more expensive, the study reveals expectations of the patients are not meant anytime the visit these hospitals. Loneliness, social isolation and social exclusion are important risk factors for ill health and mortality in older people. Conclusion: The aged are very vulnerable and fragile in living, considering their safety, mindset and values are good indicators to attract them to re access services from a healthcare Centre. Although a variety of services to aged persons are available in these hospitals, utilization of these services is adversely affected by lack of resources, personnel and complicated bureaucratic systems.

Keywords: Quality Services, Accessibility, Patient, Hospital, Healthcare Professionals

Cite this paper: Edem Segbefia, Philip Batsa Adotey, Factors Affecting the Quality Healthcare Accessibility and Delivery for the Elderly in Ghana, Food and Public Health, Vol. 12 No. 2, 2022, pp. 48-55. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20221202.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Service quality becomes the crucial issue for industries and it theories has evolved over long period of time through testing and trials in service sector. The demanding customers and increased sense of customer satisfaction led to the use of the new service parameters making healthcare centers and practitioners to implement quality management as an effective aid. During the last few decades, there is phenomenal change experienced especially in the healthcare sector (Lena A. et al 2009). However, the health sector in Ghana is both public and private. The public sector is run by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and teaching hospitals. Ghana has three teaching hospitals providing tertiary care and training for doctors. The private sector is made up of faith-based and private-for-profit health institutions. The GHS is an integrated three-tier health delivery system of primary, secondary and tertiary levels. At the primary level, a district hospital with a medical doctor serves health centres in sub-districts with physician assistants in charge. In some sub-districts there are community health planning and services (CHPS) zones where community health officers work with community volunteers to increase access to health care. A typical district with a population of 100 000 has 1 hospital, 5 health centres and 10–15 CHPS zones. According to Jane B. Boateng (2016), the system of healthcare delivery is plaque by public hospitals. The public healthcare is more accessible and cheaper than the private healthcare providers. (John Bisue 2005). Therefore most patients hold a great perception that though the private healthcare providers are of quality than the public, most of the aged decide accessing these healthcare services by the nature of their status. Currently, the largest provider of health care services is the government, (Aduboateng 2017) by the mission and then the private practitioners” (van den Boom et al., undated,). The government healthcare facilities can be distinguished in four layers depending on the services offered at the facility: village or community health posts, district clinics, regional hospitals and the two teaching hospitals” (van den Boom et al., undated, p. 4). The community health posts predominantly provide preventive and primary health care services; however, their curative treatment is limited due to the fact that they are mostly not staffed by doctors. Nurses and health workers provide first aid and refer cases to district hospitals, polyclinics, regional or tertiary hospitals, depending on the institution’s proximity and the treatment required. Hospitals and polyclinics are the main providers of curative secondary and tertiary health care. The polyclinics also serve as first point of contact of primary health care in urban centres and therefore “provide a mixture of preventive and curative care and use the regional hospitals for referrals. The regional and the teaching hospitals are usually perceived to be the provider s of higher and highest quality respectively”. The community health centres are staffed by nurses and midwifes” (van den Boom et al., undated, p. 4). According to the Ghana Statistical Service report, Ghana’s population is approximately 30.3 million people where majority are youthful as at 2020. (GSS report 2021). The aged form 35 % of this population within the ages 60 and above. Perhaps, making qualutiy healthcare available for the aged is a challenge in the country. WHO defines quality of life as “An individual's perception of life in the context of culture and value system in which he or she lives and in relation to his or her goals, expectations, standards and concerns (Obuobisa-Darko et al., 2019). Thus, it covers the individual's mental health, physical health, degree of independence, attachment to surroundings, individual beliefs and their connection with the environment. The different discursive approaches have recognized the importance of implementing health measures from a multidimensional perspective. This means that while analyzing the quality of life, factors such as the various social conditions and social, cultural, and psychological networks that exist within the different study groups should be considered (Lena A et al., 2009). We add social networks, which are a fundamental element to understand this analysis, as they are an important vector of the quality of life. However, for a general approach to the state of health from the quality of life perspective, it is necessary to consider more precise questions, and it is, therefore, important to distinguish health from life satisfaction, which involves complacency with the life of the present and past experiences. In this sense, many gerontologists claim that older people who successfully age are those who feel happy and satisfied with their past and present and enjoy positive social relationships and contacts. This concept also refers to a subjective dimension of welfare, to an adequate capacity to adapt to, accept, and recognize the environment, in order to have a better perception of health and welfare. It is about explaining how people experience their lives, their cognitive assessment, their emotional reactions, and their adaptation to life. From this perspective, it is common in professional practice to measure the quality of life according to signs of satisfactory living. More recently, the cultural context, the meaning of life for a person from a quality of life perspective, has been introduced. This shows that quality of life, in addition to being multidimensional, must take into account the person’s life experience and how they feel and interpret their life in relation to other people involved. This idea becomes more relevant in people who suffer from dementia, who need to foster their empowerment, so that they can express how they feel and their needs, when more specific stimulation is required for them. It is worth mentioning that, in recent decades, research is related to health, quality of life, and gerontology as linked subjective health with psychological welfare beyond the absence of disease (Jacques P et al., 2020). The Gwozdz and Sousa-Poza (2015) study shows that happy people can live longer, and this idea envisions interesting research prospects for the future. Previous research has already highlighted the relationship between the age evolution and happiness in the elderly. In this sense, and in line with our main research objective, professionals must look beyond the aspects related to the health of older people, that is, how to restore psychological and social crisis, as this leads to acceptance of the ageing process. Results of White’s study assessed “life experiences, describing personality, past traumas, social support, and level of activity, along with physical and psychological health, influencing levels of happiness and satisfaction in the elderly”. These findings explain the need to review the variables involved in success or satisfaction with life, such as psychological and physical health, level of activity, and social support. The combination of these factors can give a sense of usefulness and a positive feeling in the review or balance of life in the elderly. In order for a company’s offer to reach the customers there is a need for services (David, 2005).

2. Literature Review and Related Hypothesis

2.1. Culture of the Patients

- Research on service quality has stated that the relationship between perceived service quality and service loyalty requires empirical and conceptual elaboration by further studies. Research undertaken by Bloemer et al (1999) focuses on the enhancement of a level for measuring service loyalty dimensions and the associations between magnitude of quality healthcare utilisation and culture dimensions. The study suggests four dimensions of culture thus. Values, artifacts, virtues and believes. According to Gore (2012), culture forms a strong believe system of individual which is capable of altering their decision towards their life situations. He further stressed that, culture believe may affect elderly decision towards medicinal and healthcare delivery accessibility. Sinha & Ghosha (1999) have posited in their study that there is hardly any difference between manufacturing and service industries with the increasing competition of the marketplace since services have become integral part of products making all business is to be service-oriented and aimed at satisfying growing customer needs. Most of the companies are adding capacities by adapting to advanced technology and reducing cheap material imports. Gaining competitive advantage remains in providing superior value to the customer through excellent customer service with the product at a lower delivery cost. The study concluded that customer service is important factor to retain and acquire customers in competitive markets.

2.2. Safety of the Patients

- According to Doe (2008), safety is a state of mind, body free from accidents, illness, contamination and harmful incidence. Safe working conditions are among the reasons taken by when assessing choice for quality drugs. A study by Tsang & Qua (2000) to assess the perceptions of healthcare quality in among patients in 5 public hospitals, the study revealed that investigated the four gaps: between patients expectations and their actual perceptions; between practitioners‟ perceptions of patients expectations and the actual expectations of patients; Study showed that patients perceptions of healthcare quality delivery provided in the sector in Ghana were consistently lower than their expectations and those managers overestimated the service delivery as compared to tourist’s perceptions of actual service quality. They concluded that Delivery Gap and Internal Evaluation Gap were the main reasons contributing to the service quality shortfalls in the healthcare quality in China. Giving safe working environment, using safety equipment in diagnosing, safe medical practices etc are major stakes influencing patients choice of accessibility of a healthcare. Moreso, Giggs (2011), hold that safety has become a major reason who healthcare delivery. To him, patients resort to access healthcare for their safety and wellbeing hence anything compromising is not acceptable.

2.3. Patients Satisfaction

- These services depend on the type of product and it differs in the various organizations. Service can be defined in many ways depending on which area the term is being used. An author defines service as “any intangible act or performance that one party offers to another that does not result in the ownership of anything” (Kotler & Keller, 2009). In all, service can also be defined as an intangible offer by one party to another in exchange of money for pleasure. Quality is one of the things that consumers look for in an offer, which service happens to be one (Solomon 2009). Quality can also be defined as the totality of features and characteristics of a product or services that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs (Kotler et al., 2002). It is evident that quality is also related to the value of an offer, which could evoke satisfaction or dissatisfaction on the part of the user. Service quality in the management and marketing literature is the extent to which customers' perceptions of service meet and/or exceed their expectations for example as defined by Zeithaml et al. (1990), cited in Bowen & Claire 2002.

3. Materials and Methods

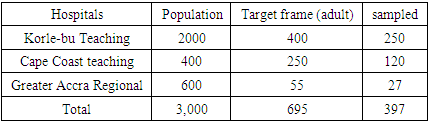

- The study considered a sample group is made up of 400 people, selected at random from the three teaching and tertiary hospitals in the Ghana. This type of random sampling is suitable for this type of research, since all people in the target frame have the same probability of being chosen, discarding those who, due to their dementia or disability, could not collaborate in the survey. The selection of participants was coordinated with the help of a technical team. Each of the interviewers chose a center to conduct the random questionnaires from the selected hospital. The surveys have been thorough and were conducted from January to May 2022. In order to improve effectiveness, four months elapsed between the first evaluation and second evaluation, with the time needed for a rigorous analysis of the results obtained in the two groups studied. Before starting, a pilot study was carried out to adapt the items or questions to the characteristics of this sector of the population. In both cases, the sample had socio demographic and health characteristics similar to those of social center users, with representative quotas by sex and age, and an age range of 50 to 80 years above for both genders. The applied research design has been a longitudinal panel design. In the first part of the empirical research, the statistical tool Wap Pls software version 7.0 was used for the inferential analysis, based on the data obtained from the validated questionnaire which is a reliable and valid scale for multidimensional measurement of quality healthcare delivery and accessibility. It is a validated questionnaire that has the psychometric guarantees of reliability, internal consistency and is very appropriate to our research objectives. It is easy to complete, of short duration (approximately 20 minutes), and measures the following areas related to quality of life: health (subjective, objective, and psychic), social integration, functional capacities, activity and leisure, environmental quality, life satisfaction, education, income, and social and health services. For the analysis of inferential statistics, descriptive results and sociodemographic variables were initially analyzed. Later, we studied both the magnitude and the significance of the association between the dependent variables and each of the independent variables (Mantel–Haenszel chi square) in both the experimental and control groups. The magnitude of the associations is expressed with odds ratios and the differences in percentages, as well as their reliable intervals. In contrast to the hypotheses of the quantitative variables, techniques such as Student’s and analysis of variance were used if the necessary conditions were met. A pilot study was conducted in the study area for a sample of 30 elderly people using the present questionnaire. Suitable modifications were made as required. After selecting the samples, the purpose of the study was explained to the individuals. After getting an informed consent, the questionnaire was given to the individuals. If the individual is not able to fill the questionnaire they were helped to fill it. Data collection was completed by making 10 visits, each time questionnaire was administered to 20 individuals between the months June to August.

|

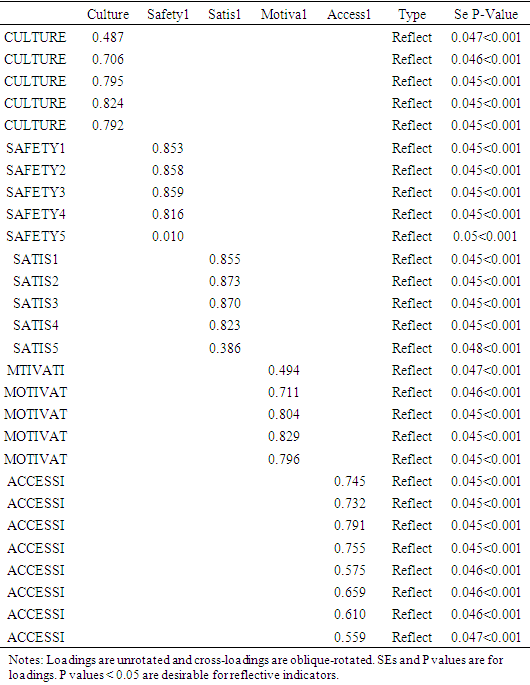

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

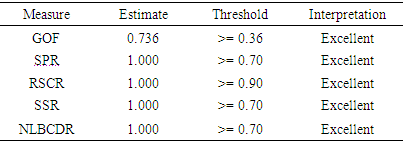

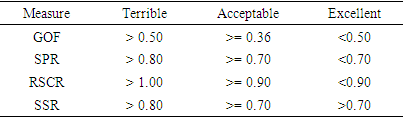

- The research reveals acceptance level of model fits, which hypothesized the structural equation measurement model. The aftermath of model fits measure were used to authenticate fitness of the model opined by (Woojin Lee, Gretzed, U. & LAW, R, 2010). The conclusion long-established the model fits for that of measurement models are essential in Table 7. Table 6 and 7 determines supplementary the outcome of model fits. However, composite reliability is encouraging at the Table 4 with the effect higher than the threshold values for latest variables. Additionally, acceptance of possibility values with coefficient of Cronbach’s alpha’s values between the composite substances. Nevertheless, the performance displays reliability of composite reliability adapted.

3.2. Validity Result

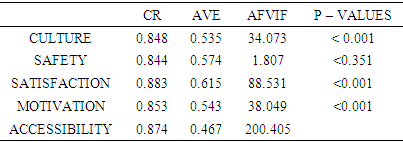

- Further to that, Convergent validity have been confirmed with affirmative factor, loading higher than minimum threshold values of 0.030 (Wetzels, M., Odekerken, Schroder G, & Van, Oppen, C 2009). Discriminant validity is passed with the result demonstrated higher values within accepted values of 0.070. The performance has also helped to analysis normality that has been optimistic. Multicolinerity is established within the relationship that has been demonstrated in the factor loadings (table 3) of low P. values of 0.05 that resulted into absence of multicolinearity among the latest variables understudy within the reflective constructs (Dai et al 2015). Variance inflation factor (VIF) constitutes accepted rule: 1= not related. Amongst 1&5=temperately connected. Superior than 5=exceedingly linked.

|

|

|

|

|

|

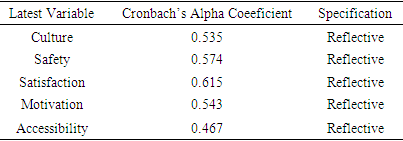

3.3. Composite Reliability

- In doing so, the study output validates Cronbach’s alpha’s coefficient value with significant composite values within the minimum threshold value of 0.30 in Table 4, all measurements revealed possibility values of reliability that displayed significant values within the benchmark values of 0.070 with the indication of huge relationship and compatible (Javis, Mackenzie & podsakoff, 2003).

4. Discussion and Analysis

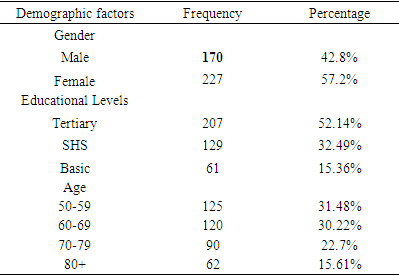

- The study engaged a sample size of 400 from a target frame of 397 representing 99.25% of the total population sampled. Out of the 400-questionnaire administered 3 were not retrieved due to patients undertaking equally important medical bid.The research is made up of Male 17 (42.8%) and Female 227 (57.2%). The educational level of respondent is Tertiary 207 (52.14%), SHS 129 (32.49%), and Basic 61 (15.36%). The age of the respondent is 50-59 (31.48%), 60-69 (30.22%), 70-79 (22.7%) and 80+ (15.61%).

5. Discussion

- The study focused on looking at the factors affecting quality healthcare accessibility and delivery among the aged. In question of gathering information, three hospitals were considered including Korle-bu Teaching Cape Coast teaching and the Greater Accra Regional. Literature review indicated that healthcare quality is considered to be an important factor in decision making concerning the accessibility of drugs among the aged. Motivation, safety and culture forms a strong believes system among the aged and that are capable of altering their decision towards their life situations. The vulnerability and fragility of the aged is immune to food and medication. The analysis shows that Culture (0.535), safety (0.574), satisfaction (0.615), motivation (0.543) and accessibility (0.467) pose a deep Cronbach’s Alpha signifying valid and reliable variable collations in fit.It is evident that majority of the respondents believes quality to be related to value of medicine and services offered to them and this could evoke satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Though quality healthcare is more expensive, the study reveals expectations of the patients are not meant anytime the visit these hospitals. Loneliness, social isolation and social exclusion are important risk factors for ill health and mortality in older people (Steptoe et al 2012; World Health Organization 2002). Curbing these death causative factors requires a careful study of healthcare type, viability, nature of service rendered and other course of action. Model fits display Culture -0.848, Safety-0.844, Satisfaction- 0.883, motivation-0.853 and accessibility 0.824 with respective P-values as < 0.001, <0.351, <0.001, <0.001, 0.001as that complex factors involved in reasons why the aged consider to access a healthcare services. Creating a safe working environment promotes healthy and appealing workers yet guarantees quality medication. Healthcare providers with sense of urgency on safety are capable of maintaining standard quality service. This quality service will intend prompt patient’s readiness to access healthcare. Consistent practices of these activities are an indication of patients’ satisfaction and motivation. The Literature holds that effective interventions to combat the aged vulnerability in accessing poor healthcare are strong safety perception and cultural disposition of patients. The goodness fit indexes 0.736, 1.000, 1.000, 1.000, 1.000 are excellent showing an indication that patients consider their safety, cultural values and motivational expectation are consistent to any healthcare services they access.

6. Conclusions

- Several choices mitigate the preference in accessibility of healthcare service. Thus increases in less viable medication can lead to chronic illness, poor safety can lead to limitations on mobility, costs of health care are likelihood to trigger less patients satisfaction which can hinder patients propensity to access healthcare services.Safety working environment, safe medication, positive mindset and values are common reactions to health accessibility. Quality is an outstanding standard meant to be perceived and feel as reality. As vulnerable and fragile of the aged, considering their safety, mindset and values are good indicators to attract them to re access services from a healthcare Centre. Although a variety of services to aged persons are available in these hospitals, utilization of these services are adversely affected by lack of resources, personnel and complicated bureaucratic systems. Moreover, the study establishes that, the aged access health care services based on quality where underlying factors such safety, medical viability, motivation and satisfaction level plays major role.

6.1. Recommendation

- During the period of data collection, the hospitals workers that were of busily working on their patients. This, as a result, could have an effect in providing accurate information, because it is likely for them to miss some vital information. The hospitals must be sure to revisit their service delivery capacity. Future research can therefore explore the same variables in other hospitals that are relatively resourced. Also, future studies should explore quality healthcare delivery in comparing the private sector and public. Analysis of the data indicated that quality healthcare delivery is positively associated with the three dimensions of healthcare delivery. Thus, effective healthcare delivery and management provides the impetus for patients to be committed affectively, normatively, and continually. It is therefore imperative that hospitals within the health sector of Ghana recognize the fact that patients are keen in their health.

6.2. Policy Implication

- According to (Boateng 2015) to attain the globally accepted standards of providing for the quality healthcare services, the Ghana health service and Ministry of health must not only reflectcurrent needs and challenges confronting health care centres but essentially carry resilient, firm and effortful message to stakeholders and employers that the nation attaches supreme prominence to the health industry. Therefore, there is the need for stakeholder engagement with the aim of mounting pressure on the lawmakers to strengthen the health related laws. This will not only bring about greater awareness of health issues in Ghana but also awareness of stringent punitive measures to patients who are victims of poor service rendered hospitals.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML