-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2021; 11(2): 35-43

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20211102.01

Received: Sep. 13, 2021; Accepted: Oct. 15, 2021; Published: Oct. 30, 2021

Microbiological and Physicochemical Characteristics of Artisanal Curd Milk Sold in Public Markets of Daloa, Côte d'Ivoire

Assohoun-Djeni Nanouman Marina Christelle1, 2, Voko-Bi Rosin Don Rodrigue1, Kouassi Kra Athanase1, Koffi Gnagne Jérémie Junior1, Kouassi Kouassi Clément1, Djeni N’dédé Théodore2

1Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé, Unité de Formation et de Recherche en Agroforesterie, Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Bio-industrie et Biotechnologie, Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire

2Université Nangui Abrogoua, Unité de Formation et de Recherche en Sciences et Technologies des Aliments, Laboratoire de Biotechnologie et Microbiologie des Aliments, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

Correspondence to: Assohoun-Djeni Nanouman Marina Christelle, Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé, Unité de Formation et de Recherche en Agroforesterie, Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Bio-industrie et Biotechnologie, Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Artisanal curd milk, commonly known as yogurt, is increasingly consumed in the Ivory Coast where it is served as a dessert or a refreshing drink. Because of its accessible cost to all budgets, it occupies a prominent place in the eating habits of Ivorians. Unfortunately, its consumption has been associated with pathologies questioning its quality. The main objective of our work was to study the microbial contamination and the physicochemical characteristics of artisanal curd milk sold in various public markets in the city of Daloa. The survey carried out to locate the knowledge, the mode and the frequency of consumption of this artisanal curd milk made it possible to show that it is a food known and consumed by many Ivorians and some nationals of neighboring countries of all ages and of any social level. A total of 15 samples consisting of 45 elementary samples were subjected to physicochemical and microbiological analysis. These samples were taken from 5 public markets in Daloa city (Abattoir 1, Grand Marché, Lobia, Orly and Tazibouo) at the rate of 3 samples per market. Physicochemical analyzes revealed low pH ranging from 3.22 ± 0.21 to 4.22 ± 0.35 negatively correlated with titratable acidity levels which varied from 1.62 ± 0.45 to 0.95 ± 0, 17. Microbiological analyzes of artisanal curdled milk samples taken from this various public markets showed high loads of fermentation germs (lactic acid bacteria, yeasts and molds) and of contaminating germs (Aerobic Mesophilic Count, total and thermotolerant coliforms). Salmonella were not detected in samples taken at the Grand Marché. On the other hand, they were present in 50% of the curdled milk samples taken at the Lobia, Orly and Abattoir 1 markets and in all the samples (100%) taken at the Tazibouo market. The presence of Salmonella which is a pathogenic flora in these samples demonstrates that this artisanal curd is not of good microbiological quality. Its consumption can automatically lead to food poisoning.

Keywords: Artisanal curd milk, Fermentation, Lactic acid bacteria, Microbial contamination

Cite this paper: Assohoun-Djeni Nanouman Marina Christelle, Voko-Bi Rosin Don Rodrigue, Kouassi Kra Athanase, Koffi Gnagne Jérémie Junior, Kouassi Kouassi Clément, Djeni N’dédé Théodore, Microbiological and Physicochemical Characteristics of Artisanal Curd Milk Sold in Public Markets of Daloa, Côte d'Ivoire, Food and Public Health, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 35-43. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20211102.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Milk is a highly nutritious food due to its richness in carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins and minerals [1,2]. A major food prized by people in arid and semi-arid regions of the world, milk is one of the most widely consumed foods in the world. In fact, milk production in the world in 2000 amounted to 489.8 million tonnes with a distribution in all continents [3]. In West Africa, one of the main forms of milk consumption is curdled milk [4]. Historically, the first fermented dairy products were obtained accidentally and in an uncontrolled manner, by curdling milk with contaminating lactic acid bacteria. These products were highly valued because of their ease of storage since their acidic pH inhibits a large proportion of degrading microorganisms as well as most pathogens [5]. Today, sour milk is increasingly produced industrially from milk supplemented with two bacterial species which are Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus salivarius ssp. thermophilus [6]. In addition, artisanal curdled milk commonly called “yoghurt” in Côte d'Ivoire is produced in households from powdered milk reconstituted in hot water (between 40-50°C) to which is added a ferment (yoghurt. commercial) consisting essentially of two bacterial species which are Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus salivarius ssp. thermophilus. At the end of this fermentation which lasts between 6 and 8 hours, the product is flavored and sweetened at will. The curdled milk is served as a dessert or as a refreshing drink. Because of its affordable cost to all budgets, artisanal sour milk is increasingly occupying an important place in the eating habits of Ivorians. In recent decades, its production in Côte Ivoire has increased because it is a source of income. Unfortunately, the consumption of artisanal sour milk has been associated with discomfort in several countries around the world and even in Côte d'Ivoire [7]. Biological contamination causes 2 billion disease episodes per year, with nearly 70% of episodic diarrhea in children under five. Also, food poisoning is a serious public health problem for both rich and poor countries. Various studies have been carried out to determine the origins of the contamination of this food very popular with the populations with a view to setting up, within these sectors, adapted control programs and preserving the health of consumers [8]. Risk analysis is seen as the best way to deal with this situation [9]. As the production conditions of artisanal curd milk do not comply with hygiene rules, the risk of contamination and proliferation of contaminating microorganisms and also of pathogens responsible for food poisoning can be high. It is therefore necessary to assess the microbiological quality of artisanal curd milk produced in Daloa in order to improve the sanitary quality of this food in order to guarantee quality products to consumers. It is in this context that this work takes place, the general objective of which is to study the microbial contamination and the physicochemical characteristics of artisanal curd milk sold in various public markets in Daloa city in Côte d’Ivoire.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey of the Consumption of Artisanal Milk

- A preliminary survey allowed to identify publics markets in Daloa city and to design a questionnaire of inquiry-consumption dedicated to curd milk consumers. The surveyed population consists of passers-by met on the main streets and side streets of five districts of Daloa town and volunteering to answer the questionnaire. In total, two hundred people were interviewed, with an average of about 40 people per ward. The survey consisted of a direct interview with the volunteers. This interview focused on the socio-demographic profile (age, study level...) of the consumer, his knowledge of milk, his mode and frequency of milk consumption and the appearance of possible symptoms of food poisoning (vomiting, diarrhea ...) related to the consumption of this food.

2.2. Sampling

- The samples analyzed in this study consisted of artisanal curd collected from five different markets in the city of Daloa. In each market, three samples were taken. These three samples were each composed of three different elementary samples taken from three different vendors. A sample consists of three primary samples. So in total, 15 samples consisting of 45 elementary samples were analyzed in this study, at the rate of 3 samples per market. Each sample consisted of approximately 200 ml of curd. Samples were collected under the conditions in which artisanal curd was sold in the markets and the collected samples were transported immediately in a cooler directly to the laboratory for analysis.

2.3. Physico-Chemical Analysis

2.3.1. pH Determination

- The pH of artisanal curd milk was determined using a pH meter (Microprocessor pH meter, pH 211, HANNA Instruments) according to the AFNOR method [10]. The instrument was calibrated using two buffer solutions at pH 7.0 and 4.0 and this was systematically done before pH measuring. The measurement was made by immersing the electrode in 20 ml of curd milk and the reading is repeated three times.

2.3.2. Total Titratable Acidity (TA) Determination

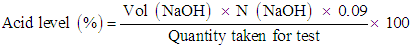

- Total titratable acidity (TA) was measured by titrating 10 mL of curd milk against 0,1N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution using phenolphthalein as indicator and the reading is repeated three times [11]. The lactic acid level (corresponding to the level of titratable acidity) was determined by the following expression:

Vol (NaOH) = NaOH volume (in ml) used for the determinationN (NaOH) = Normality of NaOH solutionQuantity taken for test = 10 mL 0.09 = Factor (in mill equivalent) for lactic acid

Vol (NaOH) = NaOH volume (in ml) used for the determinationN (NaOH) = Normality of NaOH solutionQuantity taken for test = 10 mL 0.09 = Factor (in mill equivalent) for lactic acid 2.4. Enumeration of Microorganisms

- Preparation of stock solutions, inoculation of agar plates, and cultivation and quantification of microorganisms were carried out according to Coulin method [12]. For all determinations, 10 ml of the sample were homogenized in a stomacher with 90 ml of sterile diluent containing 0.85% NaCl and 0.1% peptone (Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA). So each time, one ml of the previous dilution will be diluted in 9 ml of buffered peptone water. Dilutions of 10-2 to 10-8 were thus carried out. This dilutions prepared were placed in the Petri dishes for the determination of microbial counts. So, Plate Count Agar (PCA) was used to count Aerobic Mesophilic Count (AMC) at 30°C for 72 hours as recommended in NF/ ISO 4833: 2003. Violet Neutral Bile Lactose (VRBL) agar was used for fecal coliforms count at 44°C for 24 h and the total coliforms count at 37°C for 24 h as described in ISO 4832: 2006. Typical fecal and total coliforms colonies were confirmed by oxidase test. Yeasts and molds were counted with Sabouraud agar containing chloramphenicol 25°C for 5 days according to the NF/ISO 16212: 2011 standard. Enumeration of LAB (Lactic Acid Bacteria) was carried out using Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), which were incubated under anaerobic conditions (Anaerocult A, Merck) at 37°C for 72 h. Highlighting Salmonella sp is done in three stages (Pre-enrichment, enrichment and isolation) according to the reference standard NF/ISO 6579:2002 Amd 1: 2007. Pre-enrichment is performed in media Buffered Peptone Water (BPW) by incubating the stock solution at 37°C for 24 h. The enrichment consisted of taking 0.1 mL of the stock solution (pre-enriched) and transferred to a tube containing 10 mL of Vassiliadis Rappaport broth previously prepared and sterilized. After homogenization, the tube is incubated at 42°C for 24 h. Finally the isolation was carried out from the enrichment medium incubated on a solid selective medium: Hecktoen agar. A drop is taken using a Pasteur pipette and then seeded by streaks on the surface of the Hecktoen agar. The dish is incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and sometimes even for 48 h, in the absence of characteristic colonies after the first incubation. On Hecktoen agar, the typical Salmonella colonies observed are green or blue with a black center.

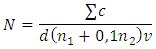

2.5. Colony Enumeration

- Colony Forming Units per milliliter of sample (CFU/ g) were calculated according to standard NF/ISO 7218: 2007 using the following formula:

ΣC: Sum of characteristic colonies counted on all retained Petri dishes; n1: Number of Petri dishes retained at the first dilution; n2: Number of Petri dishes retained at the second dilution;d: Dilution rate corresponding to the first dilution; V: Inoculated volume (mL);N: Number of microorganisms (CFU/g).

ΣC: Sum of characteristic colonies counted on all retained Petri dishes; n1: Number of Petri dishes retained at the first dilution; n2: Number of Petri dishes retained at the second dilution;d: Dilution rate corresponding to the first dilution; V: Inoculated volume (mL);N: Number of microorganisms (CFU/g). 2.6. Statistical Analysis

- All trials were repeated three times. The different sample treatments were compared by performing one-way analysis of variance on the replicates at a 95% level of significance using the Statistica (99th Ed, Alabama, USA) statistical program. Unless otherwise stated, significant results refer to P < 0.05. This software was also used to calculate mean values and standard deviations of the trials.

3. Results

3.1. Milk Consumption

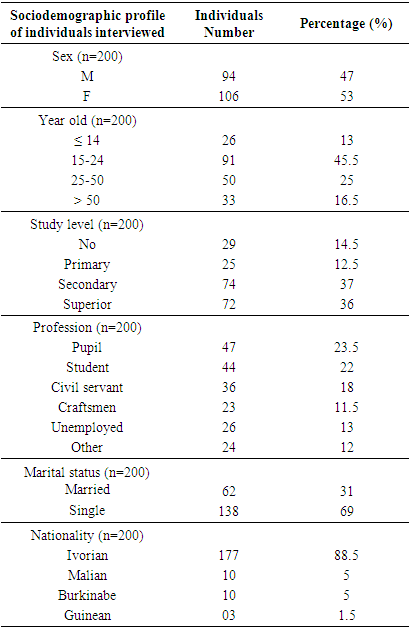

- Of all the individuals interviewed during artisanal curd milk consumption survey in Daloa City, 53% were female and 47% were male. These individuals age ranged between 15 and 50 years or more with individuals majority (45.5%) in between the 15-24 age group. Among these individuals, 14.5% were illiterate, 12.5% had the primary level, the majority (37%) secondary level and the rest (36%) had higher level. Most of them are pupils (23.5%), students (22%), civil servants (18%), craftsmen (11.5) and 12% worked in other professions. But 13% of them do not exercise or more professional activity. These individuals were mostly single (57.33%) and most of them were Ivorian (84.67%) (Table 1).

|

|

|

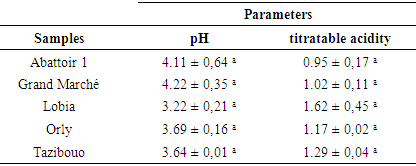

3.2. Change in pH and Total Titratable

- The results of the physicochemical analyzes of the various samples of artisanal curd milk taken from the various public markets in Daloa city are not statically different at the 5% level (P> 0.05). However, they showed relatively low pH. Thus, the lowest pH is that of the curd milk taken from Lobia market (3.22 ± 0.21) while the pH of curd milk taken from the Big Market is the highest with a value equal to 4.22 ± 0.35. These pH values are negatively correlated with the titratable acidity rate which varies from 1.62 ± 0.45 to 0.95 ± 0.17 (Table 4).

|

3.3. Enumeration of Microbial Flora of Artisanal Curd Milk Sold in the Various Markets of Daloa City

3.3.1. Fermenting Microorganisms

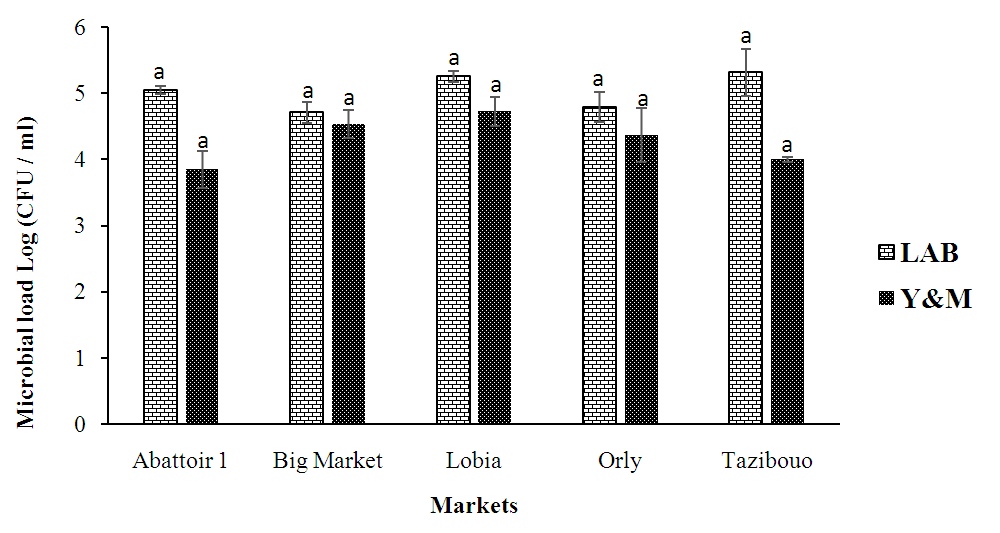

- Enumeration of microorganisms in this study showed that LAB and yeasts and molds had similar growth in curd milk samples taken from publics market and their counts in this curd milk were not significantly different (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Indeed, the load of lactic acid bacteria (5.76 ± 0.38 log CFU / ml) is higher in curdled milk from Big Market while that of yeasts and molds (4.45 ± 0.06 log CFU / ml) is higher in curdled milk from Abattoir 1 market. The lowest loads which are 4.50 ± 0.18 log CFU / ml for lactic acid bacteria and 3.28 ± 0.35 log CFU / ml for yeasts and molds were observed respectively in curd milk of the Abattoir 1 market and that of Orly market (Fig. 1).

3.3.2. Contaminating Germs

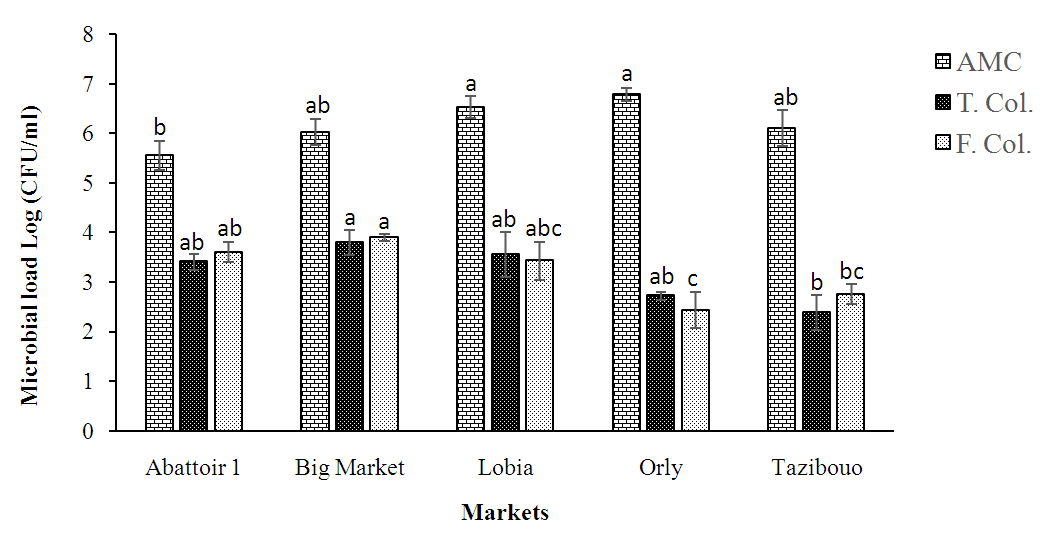

- The evolution of the average load of AMC, total and fecal coliforms in the samples of artisanal curd milk taken from the various public markets of Daloa city is presented in fig. 2. This results showed that the loads of AMC, total and fecal coliforms in this curd milk were significantly different (P < 0.05). The Big Market contains the highest loads of Aerobic Mesophilic Count (6.37 ± 0.03 log CFU / ml) while Orly market has the lowest loads (4.82 ± 0.15 log CFU / ml). In addition, the curd milk collected at the Abattoir 1 market contain the greatest number of total coliforms (3.41 ± 0.27 log CFU / ml) and thermotolerant coliforms (3.34 ± 0.05 log CFU / ml). The lowest loads of total coliforms (2.59 ± 0.22 log CFU / ml) and thermotolerant coliforms (2.13 ± 0.09 log CFU / ml) were observed in curd milk collected at the Tazibouo market (Fig. 2).

3.3.3. Presence of Salmonella Presumptive Strains

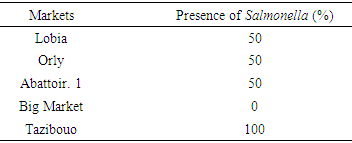

- The presumptive identification of salmonella in curd milk samples is presented in Table 5. Thus, this table shows the presence of salmonella in 50% of the curd milk samples taken at Lobia, Orly and Abattoir 1 markets. Also, this pathogenic germ has been detected in 100% of samples collected at Tazibouo market. On the other hand, Salmonella were not detected in curd milk samples collected at Big market.

|

4. Discussion

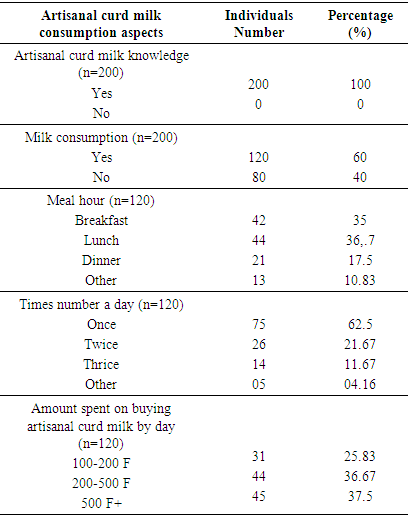

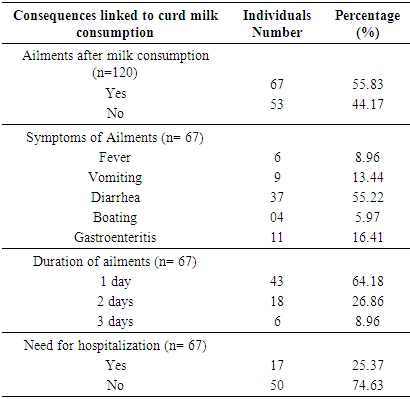

- Artisanal curdled milk is a dessert increasingly consumed by people in Côte d'Ivoire, especially in the town of Daloa. The proof is that, during the survey carried out on the consumption of artisanal curd milk, 100% of the people questioned (200) affirmed to know this food and 60% of these people consume it regularly (Table 1). They consume it at least once a day, preferably at lunch (36.67%) and pay more than 500 FCFA per day for the purchase of curdled milk (Table 2). In addition, some people surveyed (55.83%) claimed to have had ailments following the consumption of milk (Table 3). These results are in agreement with the work of Maïwore et al. [13] on fermented milks in Maroua in Cameroon. Indeed, survey carried out on artisanal curd milk consumers have revealed that many cases of diarrhea have been detected. Indeed, in Latin America as well as in Asia and Africa, millions of people have symptoms of the intestinal infection giardiasis, which is primarily spread by feces-contaminated water-causing diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rapid weight loss [14]. These ailments, characterized most often by diarrhea (55.22%) and gastroenteritis (16.41%) in our study, are generally attributed to the ingestion of a food of poor cooking and / or having been the subject of handling defective as pointed out by Olshansky et al. [14] and Farthing [15]. The ailments, marked by a high rate of diarrhea and gastroenteritis, are characteristic of toxi-infections caused particularly by sulfite-reducing Clostridium [16]. Indeed this curd milk is made in an artisanal way by persons with very little knowledge of hygiene; which would encourage excessive contamination of this food. Artisanal curd milk commonly called “yoghurt” in Côte d'Ivoire is produced from powdered milk reconstituted in hot water (between 40-50°C) to which is added a ferment (commercial yogurt) consisting essentially of two bacterial species which are Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus salivarius ssp. thermophilus [6]. Under optimal conditions, milk fermentation lasts on average between 6 and 8 hours and this fermentation is the source of the sour taste of curd milk. During this study, physicochemical parameters (pH and titratable acidity level) were measured. Thus, the artisanal curd milk samples taken from 5 public markets (Abattoir 1, Big Market, Lobia, Orly and Tazibouo) in Daloa have a low pH of between 3.22 ± 0.21 and 4.22 ± 0.35 associated with a titratable acidity rate ranging from 0.95 ± 0.17 to 1.62 ± 0.45 (Table 4). Thus, the artisanal curd milk samples taken from 5 public markets (Abattoir 1, Big Market, Lobia, Orly and Tazibouo) in Daloa have a low pH of between 3.22 ± 0.21 and 4.22 ± 0.35 associated with a titratable acidity rate ranging from 0.95 ± 0.17 to 1.62 ± 0.45 (Table IV). The different pH values obtained during this study are more acidic compared to those of Mulonda [17] obtained on curdled milk from Bukavu in the Democratic Republic of Congo with less acidic contents between 4.3 and 5.5. Ngassam [18] and Dieng [19] obtained pH values respectively between 4.38 and 4.98; and 3.96 and 4.9 on artisanal fermented milks marketed in Senegal. On the other hand, Omola et al. [20] obtained pH values ranging from 1.44 to 5.35 on yogurts sold in the metropolis of Kano in Nigeria. It should be noted that the milk before fermentation has a pH approaching neutrality. Thus, the drop in the pH of artisanal curd milk taken from Daloa city publics markets is linked to the fermentation that takes place during the manufacture of this food. In fact, during the fermentation of milk, the lactic acid bacteria present in the ferment used to make curd milk ferment the lactose to produce lactic acid. This results in a decrease in pH and an increase in acidity over time, responsible for milk casein coagulation and product bio-preservation [21]. These lactic acid bacteria produce several aromatic compounds, enzymes and other compounds that have a profound effect on the texture and taste of dairy products [18,22]. These results are in agreement with those of Zhihai et al. [23] who showed a drop in pH correlated with an increase in the titratable acidity level during the fermentation of goat milk in China. These authors have shown that this phenomenon was due in particular to an accumulation of lactic acids linked to the metabolism of lactic acid bacteria. It should also be noted that acidity is an important indicator of the quality of fermented milks [24]. Appropriate acidity gives the product a unique flavor and inhibits the growth of spoilage and / or pathogenic germs [25]. The difference between artisanal curd milk samples pH taken from the vendors in the different markets could be explained by the fact that the artisanal production of curd milk takes place in an empirical and uncontrolled way. This phenomenon causes a permanent variation of certain physical parameters such as the fermentation time and temperature which inevitably influences the quality of the final product. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Ngassam [18] and Dieng [19] who confirmed this assertion during a study carried out on artisanal fermented milks marketed in Senegal. During this study, the microbiological parameters of artisanal curd milk collected from the various public markets in Daloa were also analyzed. Indeed, the results showed the presence of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts and molds in these samples taken. Contaminating germs were also found in the samples analyzed during this work. Thus, significant loads of Aerobic Mesophilic Count and coliforms were detected in the different samples analyzed and these loads varied from one market to another (Fig. 2). These mainly contaminating microorganisms must certainly have contaminated the milk during manufacturing under generally unsanitary environmental conditions. Indeed, the surrounding air, utensils used for curd milk production and water could constitute the main sources of milk contamination. Such elements (water, utensils, etc.) are major sources of food products contamination [26]. Non-compliance with hygiene rules by producers and curd milk sale conditions, particularly the lack of sufficient refrigeration or sale at room temperature could also be contamination sources. Also, containers used during the manufacture of fermented milk can be the source of contamination of the milk as well as of the final product [27]. In addition, Ndiaye [28] affirmed that the pH of the milk is favorable to the development of microorganisms but their number decreases as the fermented milk ages. Dairy products in general and fermented milks in particular must be well preserved throughout the cold chain, whether at the producer, distributor or consumer to avoid possible contamination [29]. The results of these microbiological analyzes also showed high coliform loads (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with those obtained by Beukes et al. [30] who showed the presence of high coliform loads in traditionally fermented dairy products (“Lben” and “Jben”) in Morocco. Ngabet Njassap [31] in his study found that 57% of artisanal curd milk in Cameroon were contaminated with coliforms. High loads of coliforms in food reflect unsatisfactory hygienic practices and the presence of Escherichia coli implies that other enteric pathogens may be present [32,33]. Their numbers should therefore be within the maximum recommended levels. The presence of fecal coliforms could reflect inefficient pasteurization of contaminated ingredients or contamination by environment after pasteurization as showed by Smoot et al. [34] in their work. It should also be noted that the presence of coliforms in food most often indicates exogenous contamination of fecal origin. Indeed, most of the curdled milk producers do not have a running water supply installation. The cleaning of the utensils is therefore done with water which is not always drinkable. According to Niculescu et al. [35], most of the plastic containers used in the dairies were scratched, which could hinder satisfactory cleaning. Indeed, most sour milk producers use polyethylene plastic buckets as fermentation vessels. The homogenization of the ingredients during the manufacturing process of artisanal curd milk being done energetically using a metal spatula. So, the internal walls of the containers could be lined with tiny and large cracks which could harbor many germs if these containers are poorly washed or rinsed with non-potable water. This may explain why the numbers of coliforms were high in artisanal curd milk collected in Daloa city publics markets. In addition, Salmonella presumptive strains have been found in 50% of the curdled milk samples from Lobia, Abattoir 1 and Orly markets. These salmonellae has been found at 100% in the samples of curdled milk taken at Tazibouo market (Table 5). However, they were absent in samples from Big Market. These results are in agreement with those of Gran et al. [36]. Indeed in their works, none of fermented products samples in Lebanon was contaminated by Salmonella. It should be noted that during curd milk production, lactic acid bacteria responsible for milk fermentation produce metabolites (lactic acids, hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocin, etc.) which eliminate coliforms and even certain pathogens in curdled milk [7]. The absence of Salmonella in curdled milk samples taken from certain markets would certainly be due to the bactericidal effect of these metabolites [13]. On the other hand, the presence of these enterobacteriaceae in some curdled milk samples collected could be due to the faulty handling of this curd milk by the women during the sale. Indeed, curdled milk is often sold on the edges of the streets or inside the market on tables in open containers. Flies and surrounding dust land on curd milk and utensils used for sale [7]. Also, the rinsing water for these sales utensils (funnels, ladles, etc.) is hardly renewed by the women who sell curd milk. The many rings on the fingers of these women as well as the bracelets on the wrists can be excellent niches for the multiplication of microorganisms. In addition, some of these women who sell curd milk have young children and do not take adequate sanitary precautions after their children's toilet. All these badly clean gestures could be lead the excessive contamination of artisanal curd milk. High loads of fermentative germs (lactic acid bacteria and yeasts and molds) were observed in artisanal curd milk samples taken from the various markets in the town of Daloa (Fig. 1). Elham et al. [37] also indicated lactic acid bacteria as well as yeasts and molds presence in their works and their importance in fermented products. Zhihai et al. [23] also showed the presence of these microorganisms during the fermentation of goat milk in China. The presence of yeasts and molds in most of the samples would be due either to poor storage and preservation conditions, or to incomplete pasteurization because these microorganisms are heat sensitive. The yeasts has been found in fermented milks as showed Vieira-Dalode et al. [38] on yogurts sold in Benin. Also, these microorganisms are not bothered by acidity and therefore grow very easily in fermented milk. It should also be noted that these fermentative germs evolve in a similar way. These results are in agreement with those of Coulibaly et al. [39] who reports that the survival of lactic acid bacteria during fermentation generally occurs in association with yeasts. Unlike contaminating germs, the abundance and maintenance of yeasts, molds and lactic acid bacteria in artisanal sour milk would surely be linked firstly to their capacity to tolerate high organic acids concentrations of and therefore to low pH, and on the other hand, their ability to use the substrates present in the fermentative medium for their development. These germs live in symbiosis. Sanni [40] also have shown that there is a co-metabolism between these two microorganisms’ types (LAB and yeasts and molds). During this co-metabolism, the lactic acid bacteria provide an acidic environment that selects yeasts growth while the yeasts provide vitamins and other growth factors for lactic acid bacteria. Yeasts also contribute to the flavor and acceptability of fermented products according to these same authors.

5. Conclusions

- This study objective was to study the microbial contamination and the physicochemical characteristics of artisanal curd milk sold in Daloa publics markets. Thus the results obtained during this study show a food with pH ranging from 3.22 ± 0.21 and 4.22 ± 0.35 negatively correlated with titratable acidity levels ranging from 0.95 ± 0.17 at 1.62 ± 0.45. High fermentative germs loads were observed in all the samples analyzed. As for the contaminating germs, they were also present and abundant in the artisanal curd milk collected on the various markets with loads largely exceeding the microbiological quality standards of fermented milk. Salmonella were present in samples collected in Lobia, Abattoir 1, Orly and Tazibouo markets. The presence of this germ indicate that the artisanal curd milk collected is of poor quality, therefore, the consumption of this food could constitute a significant health risk for the consumer.

Conflict of Interests

- The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research was made possible through funds provided by The World Academy of Sciences, Italy (N° 19-120 RG/BIO/AF/AC_I), with the important contribution of the microbiology team of Laboratory of Biotechnology and Food Microbiology, Faculty of Food Sciences and Technology, University Nangui Abrogoua, Cote d’Ivoire. The authors gratefully acknowledge Prof. Marcellin Dje Koffi, the director of the laboratory.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML