-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2020; 10(2): 35-47

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20201002.01

Comparing the Prevalence of Maternal HIV in Resource Poor and Rich Settings

S. Fiatal, J. Y. Bagayang

Faculty of Public Health, University of Debrecen, Hungary

Correspondence to: J. Y. Bagayang, Faculty of Public Health, University of Debrecen, Hungary.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

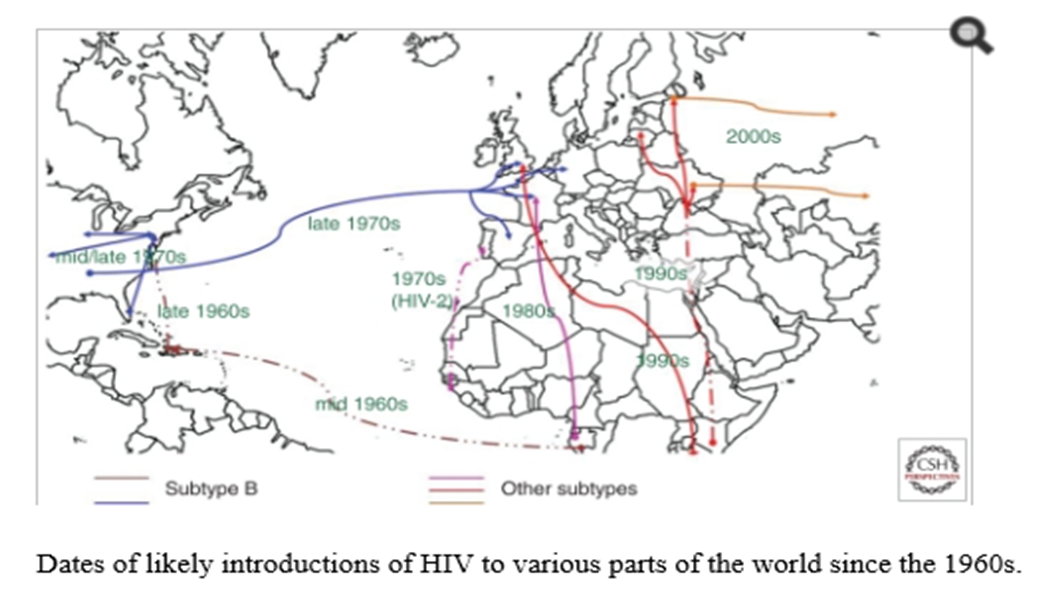

Several studies indicate that HIV-infected women continue to have children. The main aim of this study is to determine the trend in HIV transmission at subsequent pregnancies, the factors responsible for the unequal prevalence of maternal HIV in both resource-rich and resource-poor settings and the 2016-2021 HIV reduction strategies proposed by WHO and the financial backing of these strategies. From the literatures reviewed, one of the results showed pregnant women who were enrolled in single dose nevirapine-base Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programme and the period they observed exclusive breastfeeding. At the subsequent pregnancy, HIV-infected children had a similar duration of exclusive breastfeeding periods (4.2 months [SD 2.6] versus 6.2 months [SD 3.3] for uninfected children, OR 0.76 [0.57–1.02]). At the initial pregnancy 37.5% of mothers did not receive single dose nevirapine transmitted versus 36.8% of those who did receive nevirapine (OR 1.12 [0.23–5.34]). For the subsequent pregnancy, the percentages were 22.2 and 10.2, respectively (OR 2.51 [0.43–13.37]). This result, statistically demonstrate no significance/correlation in the single dose nevirapine-base HIV PMTCT programme and the period of exclusive breastfeeding in averting vertical transmission in a resource-poor setting even with the advent of antiretroviral therapy and advancement in technology.

Keywords: Prevalence of HIV, HIV risk factors, Maternal HIV complications, ARV regimen

Cite this paper: S. Fiatal, J. Y. Bagayang, Comparing the Prevalence of Maternal HIV in Resource Poor and Rich Settings, Food and Public Health, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 35-47. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20201002.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

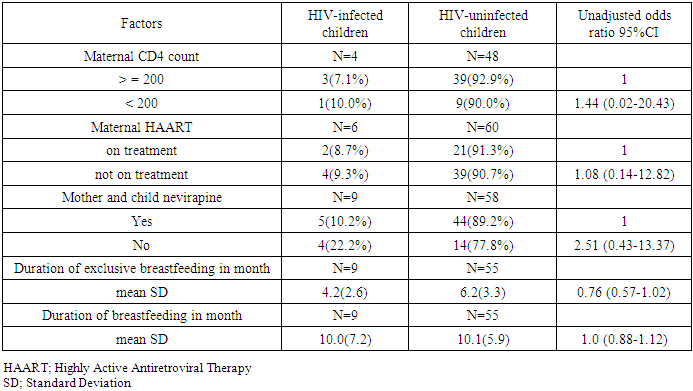

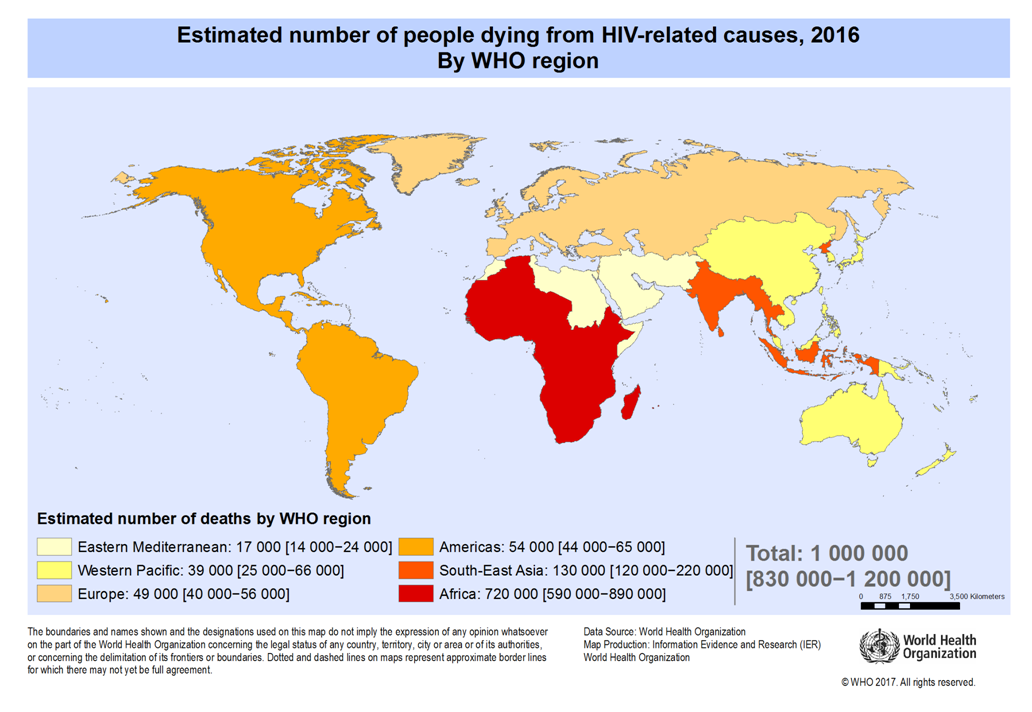

- HIV is a virus spread through body fluids that attacks the body’s immune system, specifically the CD4+ cells, often called T cells. These special cells help the immune system fight off infections. Untreated, HIV reduces the number of CD4+ cells in the body. This damage to the immune system makes it harder and harder for the body to fight off infections and some other diseases. Opportunistic infections or cancers take advantage of a very weak immune system and signal that the person has AIDS [1].Globally, the number of people living with HIV is 37.9 million (32.7 million – 44.0 million), newly HIV infected persons in 2019 is 1.7 million (1.4 million - 2.3 million) and deaths due to AIDS in 2019 is 770 000 (570 000 – 1.1 million) [2]. The below map (Figure 1.1) indicates the global percentages of adult HIV prevalence (15-49 years), with the highest endemic region being Africa. (America, Europe, South-East Asia, Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific) have prevalence of 0.5% or less, which demonstrates a lower prevalence rate.

| Figure 1.1. Adult global HIV prevalence |

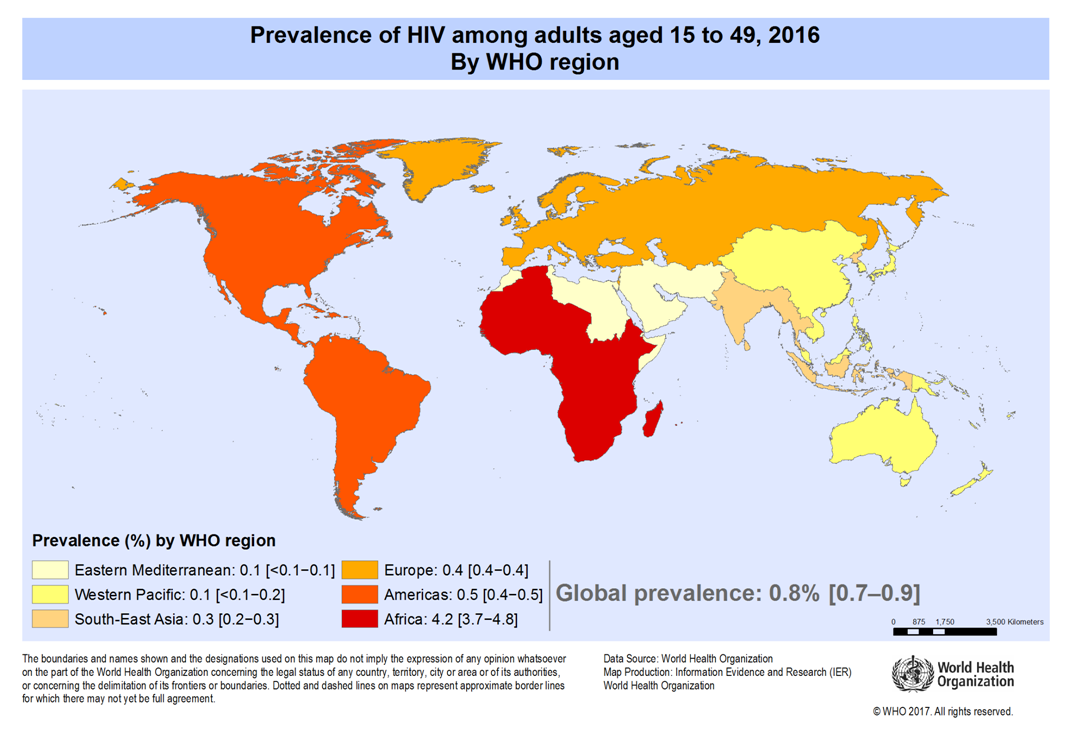

| Figure 1.2. Phylogenetic analysis of HIV |

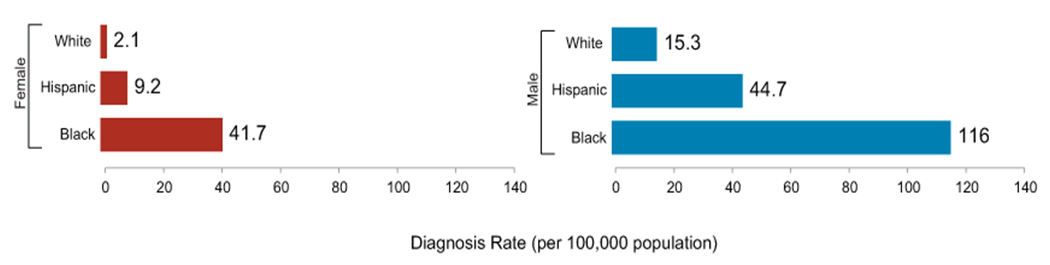

| Graph 1.1. Racial HIV prevalence in the US |

| Figure 1.3. Adult and Child death to AIDS |

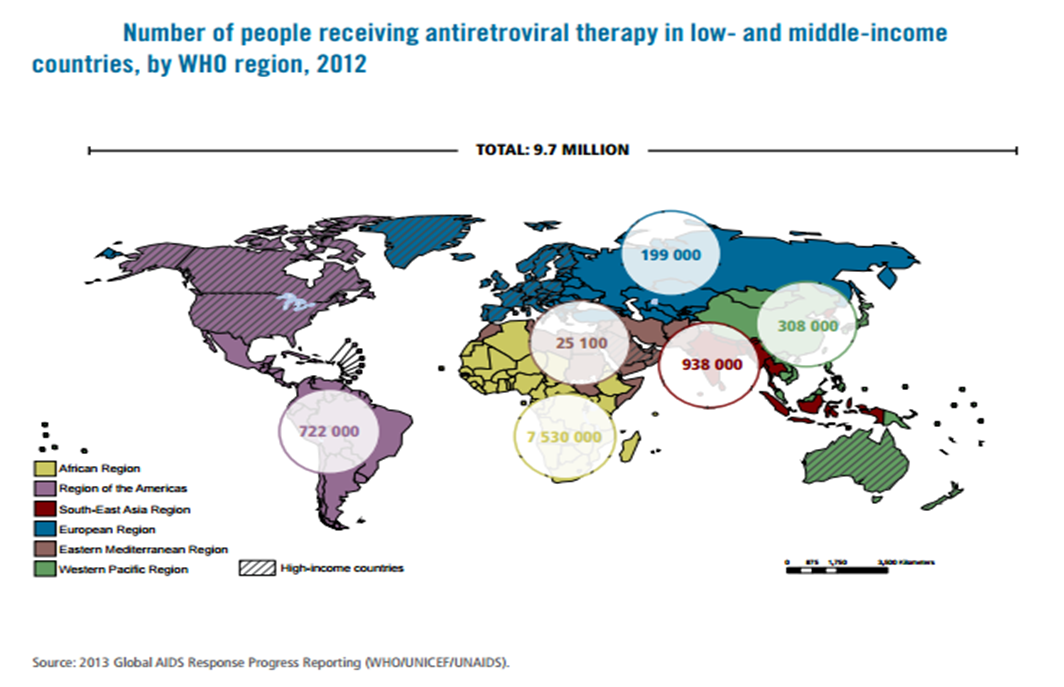

| Figure 1.4. The world's population of ARV recipient |

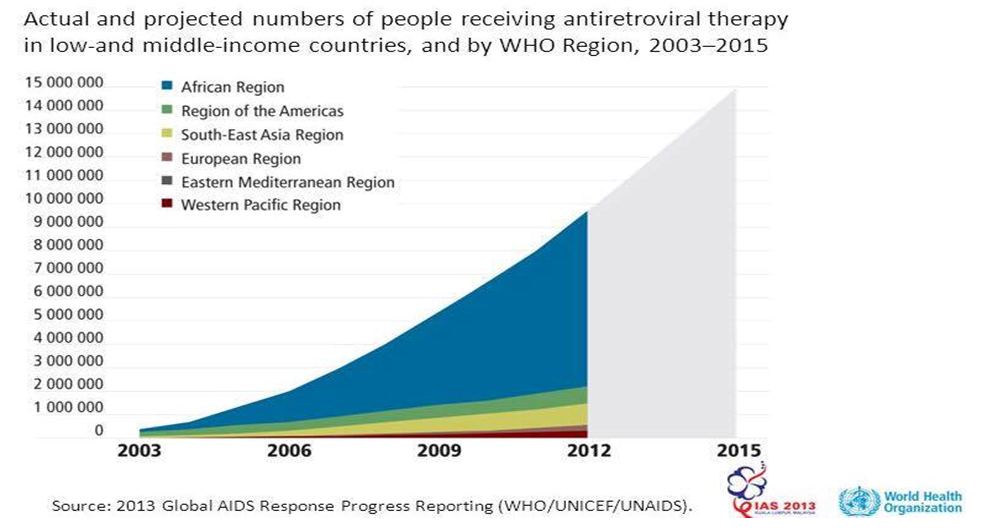

| Graph 1.2. Number of patient receiving ART |

2. Methods and Materials

- A comprehensive literature search was done to identify articles containing information on prevalence of maternal HIV. The following PubMed searches were used, keywords: prevalence of HIV, HIV risk factors, maternal HIV complication and ARV regimen. It was filtered to free articles, English, last 15 years, and human. Google scholar was used only to search for specific papers identified from the reference lists of published papers. These search terms were designed to be more broad than precise. Relevance to the research question was determined by review of the abstracts. The full texts of articles with relevant abstracts were reviewed to determine if the articles should be included according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles were included regardless of language in which they were written. PubMed is the largest database containing scientific articles that are written about health and medical related issues.PRISMA principles [29] were strictly adhered to; it is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA focuses on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials, but can also be used as a basis for reporting systematic reviews of other types of research.The other sources of data and strategy for HIV for the period of (2016-2021) were obtained from WHO, which is responsible for setting pace when it comes to international health, CDC as Center for Disease Control, and Figure and tables for comparing different countries were obtained from HFA Europe database.The countries were categorized by gross national income as defined by the World Bank: high income, middle income (upper middle and lower middle), and low income [30].

3. Result

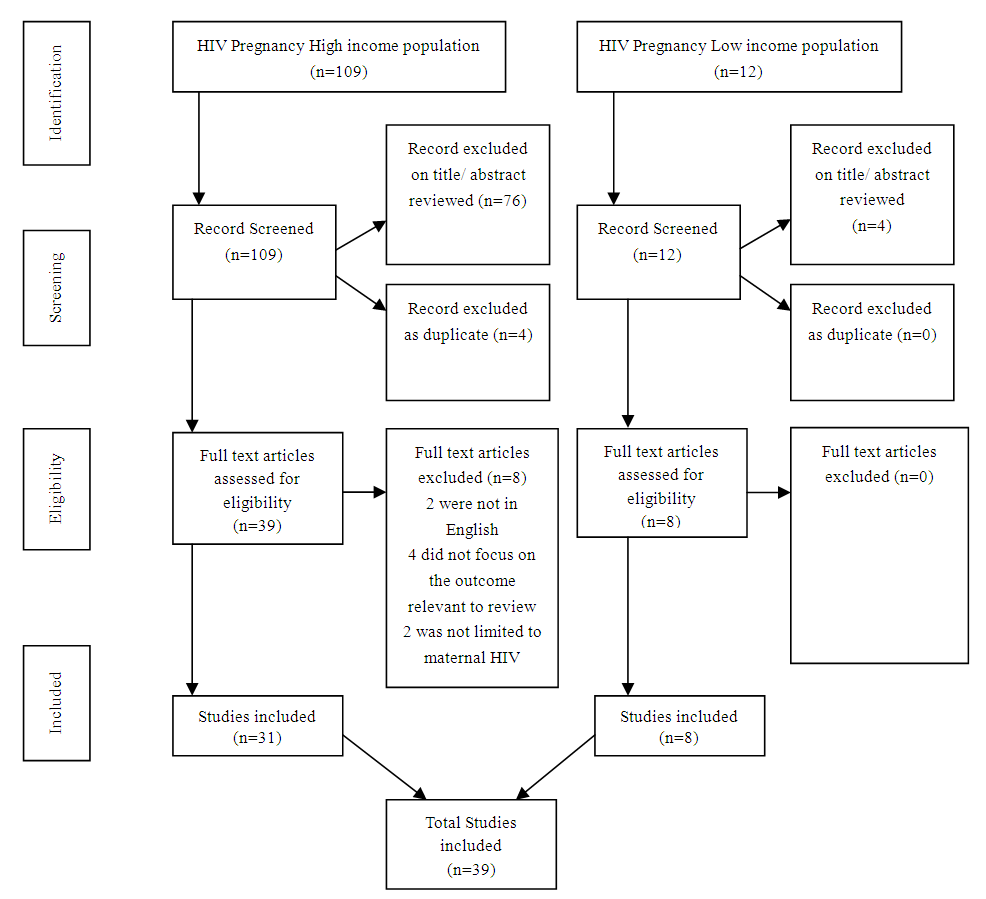

- The flow chart (Figure 3.1) is based on PRISMA principle, a total of 121 titles and abstracts were identified for screening; 39 papers and abstracts were included in the full review while 82 papers and abstracts were excluded. On July 6, 2016, the literature search was done.

| Figure 3.1. Flow chart |

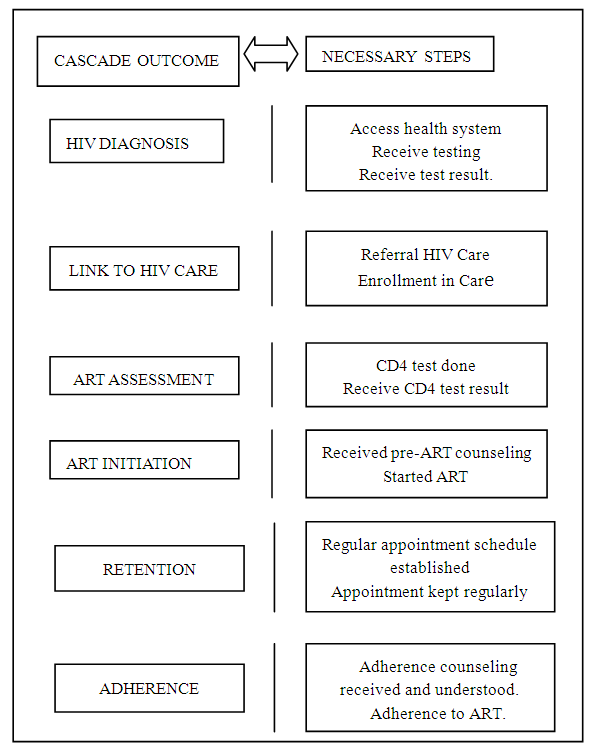

| Figure 3.2. Maternal HIV cascade |

|

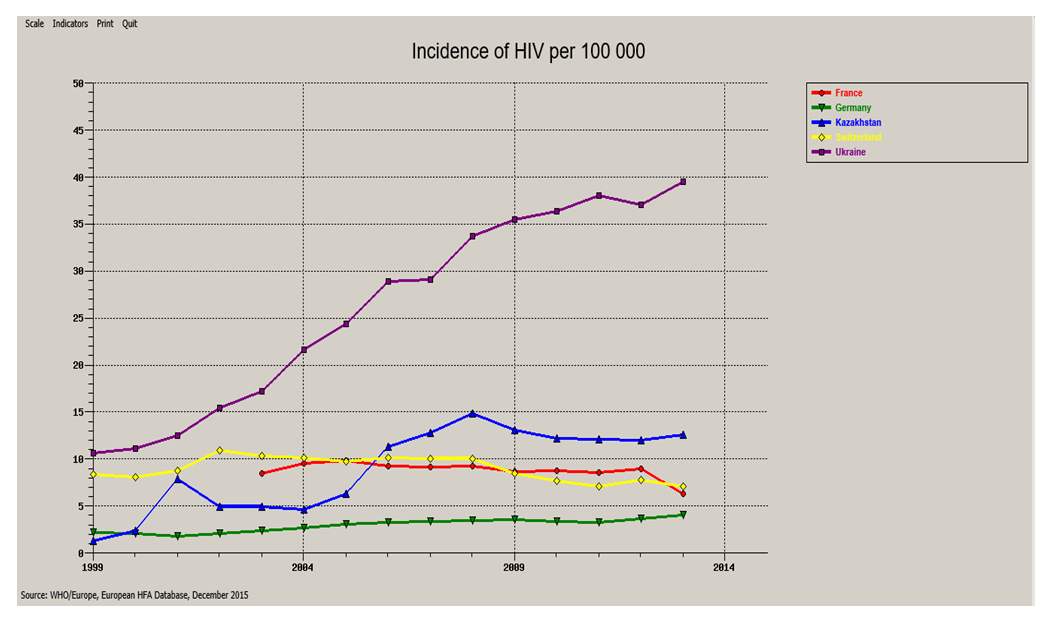

| Graph 3.1. The incidence of HIV from (1999-2013) in high and low income country |

4. Discussion

4.1. Human Resources Shortage and Workload as a Major Factor Responsible for the Unequal Global Maternal HIV

- There are critical human resource shortages in all areas of health care throughout Africa and most low income countries around the globe. Absolute shortages are compounded by inequitable distribution between urban and rural areas, as well as heavy workloads, insufficient training, weak management and low staffing ratios which increase stress and burn-out for health workers, contributing to poor quality care [34]. Low-income women face many threats to their health and well-being. Relative to affluent women, low income women experience enhanced vulnerability to almost every disease and show higher rates of mortality [35].Furthermore, the lack of human resources available to provide HIV care and PMTCT are illustrative of the severity and consequences of these shortages which are also present in other areas of MCH service provision and across the health system, which ultimately accounts for the differences in prevalence between resource limited and high income countries. For instance, an estimation of the human resources needed to deliver universal coverage of ART in sub-Saharan Africa by 2017 found that this could only be achieved if the population of health workers doubled each year over a decade and factors such as out-migration were kept to a minimum [36]. A modeling study which looked at the financial and human resources needed to provide recommended interventions for maternal and child health in the context of PMTCT in seven sub-Saharan African countries found that only three countries (Rwanda, Burkina Faso and Zambia) had sufficient funds (mostly from foreign aid) and only one (Zambia) had sufficient human resources to scale up the interventions by 2010 and sustain them to 2015 [37].From (figure 3.2, 3.3) the rapid expansion of programmes to improve coverage should neither compromise the quality of services nor contribute to inequities in access to services and health outcomes. Countries like Ukraine and Kazakhstan and the entire Africa continent (low resource) should monitor the integrity of their continuum of maternal HIV services to determine where improvements can be made. Services should be organized to minimize “leakages” and maximize retention and adherence. Major challenges include: acceptability and uptake of effective prevention interventions; targeting HIV testing and counseling to achieve greatest yield; ensuring quality of testing to minimize incorrect diagnosis; linking people diagnosed to appropriate prevention and treatment services as early as possible [38].However (table 3.1) the main point is that the HIV transmission rates at subsequent pregnancies might be lower but not complete prevention because of improved PMTCT in the breastfeeding resource-limited setting and the profound CD4 count which is significant in the estimation of transmission rate of HIV. This is an important factor when counseling HIV-infected women who want to have more children. Maternal HAART should be made more accessible for women at least from 35% to 100% in this setting, as it has been shown to have effect in the improvement programmes.Consequently, the unequal prevalence of maternal HIV as stated, in 2012 by the United Nations Interagency Task Team on the Prevention and Treatment of HIV Infection in Pregnant Women and Children stated bluntly that at the present time there are simply not enough health workers in the 22 countries with the highest burden of mother-to-child HIV transmission to meet the goals of the Global Plan for the Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV and keeping their mothers alive [39].In short, these findings suggest, not surprisingly, that the quality of antenatal counseling for both women living with HIV and HIV negative women was negatively impacted by limited human resources and the level of mothers’ education which can also be accounted for as a factor leading to the unequal prevalence of maternal HIV case in both settings (resource limited and resource rich).

4.2. Overcoming the Challenges to PMTCT in Resourse Rich Settings

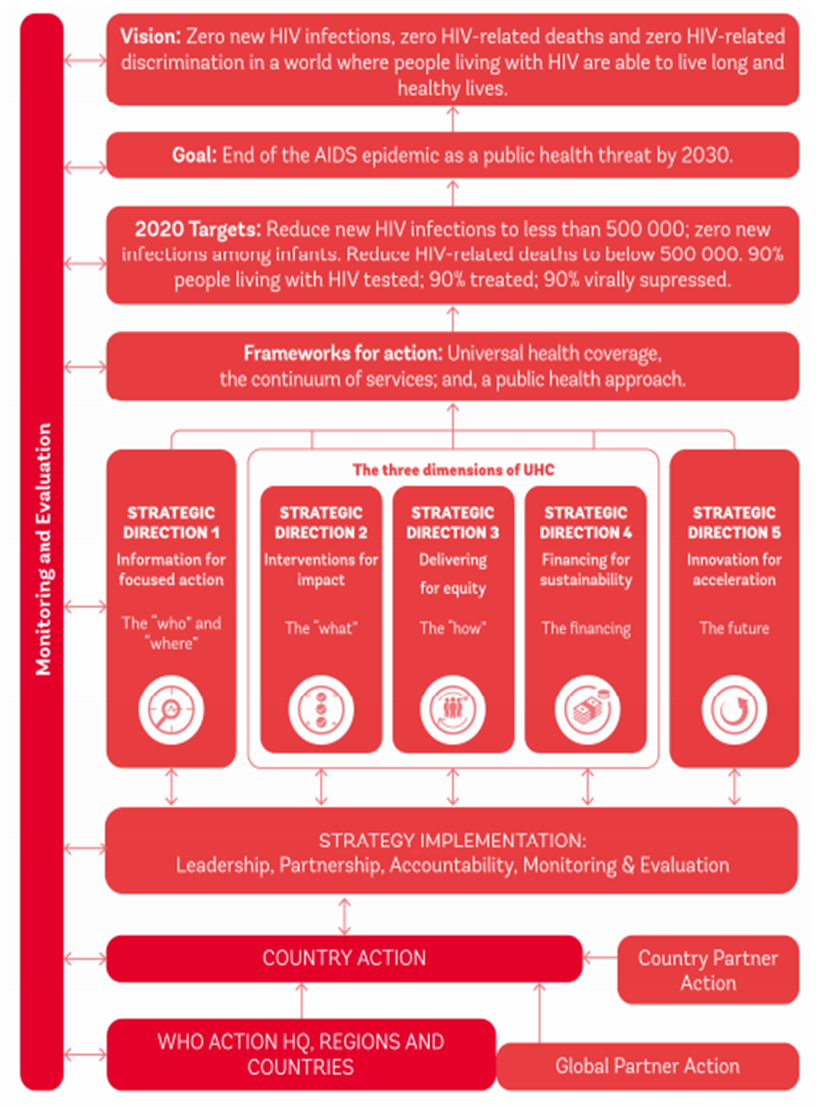

- In countries with low prevalence like (France, Switzerland, Germany), [figure 3.2] there is Community monitoring and accountability mechanisms which generate political will for better service quality, demand for services, and social support to women living with HIV which ultimately improve health outcomes. And most women living in these countries are always exposed to ART whenever they conceive which equally plays a key role in combating maternal HIV-transmission rate. Immigrants from lesser-resourced countries account for an increasing proportion of HIV exposed deliveries in mostly high income countries [40]. Though from (figure 3.2 and 3.3) immigrant HIV-infected women of childbearing age comprise an increasing percentage in many resource-rich countries, their PMTCT problems relate more to health care access and utilization than to biomedical issues. There seems to be better health services in those countries (Germany, France and Switzerland) which evidently reflect in their country’s incidence and prevalence of HIV which could be as a result of adequate public health awareness, investing more on the health sector and good human resource managements. In the US, most of the ongoing mother-to-child transmissions are apparently attributable to incomplete uptake of elements of the Perinatal Prevention Cascade, as included in (figure 3.2) e.g., identification of HIV-infected women and effective retention of them in care [41].The expansion in medical care access in the U.S. anticipated from the Affordable Care Act may mitigate some of poverty's effects unlike some resource-limited countries like Nigeria, but it can be predicted that the social instability and segregation associated with poverty will continue to aggravate problems of access in both settings [42]. Indeed, in this era of low MCT rates, as each transmission's specific characteristics take on heightened importance, it remains important to review cases, with the goal of changing the local system in ways that may prevent further transmissions and improve the care of HIV-infected women to optimize their health prior to —and between—pregnancies, as well as to prevent unwanted pregnancies.The figure 4.1 was not among the 39 articles that were included for the study; it was gotten from the WHO website. WHO maps out the strategies for the elimination of HIV from 2016-2021 and the financial estimate when implementing the strategy. The above WHO draft focuses explicitly on steps to be taken to avert HIV incidence to zero and zero HIV related death, which ultimately mean, eradicating HIV epidemic as public health threat by 2030 by adopting the Universal Health Coverage [UHC] strategies in partnership with leaders of countries and regions of the world.

4.3. Financial Implication of Maternal HIV Cure and Future Trends (Who 12.01.2015 Drafts)

- However, the resources mobilized from all sources for HIV programmes in low- and middle-income countries increased by an additional US$ 250 million from 2012 to reach US$ 19 100 million in 2013 and then increased again to an estimated US$ 21007 million in 2015. The rising trend was due mainly to greater domestic investments, which comprised about 57% of the total in 2014. Nevertheless, investments in HIV will need to grow to US$ 31 900 million in 2020 and US$ 29 300 million in 2030 if long-term control of the epidemic is to be achieved [42].The Global health sector strategy on HIV, 2016–2021, from (figure 4.1) describes the health sector contribution to the goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. The costing of implementation of the strategy has been undertaken based on the costing of the UNAIDS 2016-2021 Strategy, which used specific targets and unit costs for the interventions included in the strategy. The total costs of the present draft strategy (figure 4.1) are estimated to rise from about US$ 20 000 million in 2016 to just over US$ 27 000 million in 2020 before declining somewhat to US$ 26 000 million in 2021. Antiretroviral therapy requires the largest amount of resources, about 36% of the total. Prevention for people who inject drugs is the next largest component at 13% and HIV testing services are next at 11%. One quarter of all resources is required for four countries (in order of burden): South Africa, Nigeria, Brazil and China. The top 20 countries account for 65% of needs. Just over half of all resources (53%) are needed in sub-Saharan Africa. The next largest region is Latin America and the Caribbean at 18%, followed by Eastern Europe and Central Asia at 9%, South-East Asia at 7%, the Western Pacific at 7% and the Eastern Mediterranean at 6%. About one-third of resources are needed in low-income countries and about one-quarter in lower middle-income countries [42].

| Figure 4.1. Outline of the global strategy on HIV 2016-2021 |

4.4. Conclusions

- These findings suggest a strong relationship between GDP of a country, workforce, and advancements in technology as factors responsible for the unequal prevalence of maternal HIV in both resource-limited and resource-rich settings, in different regions of the world.With limited available resources, countries need to plan carefully, setting ambitious but realistic targets, and develop strong investment cases. The investment case should provide justification for an adequate allocation of domestic resources, facilitate the mobilization of external resources and help identify global partners who would support their efforts in combating maternal HIV. The investments being made to reduce the prevalence of maternal HIV mortality and increase access to HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa and other resource limited regions of the world over the years are so far significant. The scope of these investments should further be reflected in support for further research, training of qualify health personnel’s and volunteers for easy access of ART to infected women and evaluation that fills priority knowledge gaps and assesses the impact of these investments on health outcomes. Vital registration and health information systems need to be strengthened by improving access to ART; implementing health promotion programs combined with HIV risk-reduction strategies; and scaling up HIV screening to identify infected patients early enough and link them to care by proven strategies toward reaching this goal. When all this measures are put in place, no doubt a free maternal HIV world and perhaps a better world would be sustained for the present and future generations yet unborn.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML