-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2020; 10(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20201001.01

Comparison of Dietary Diversity among Women-Child Pairs from Households Participated in Integrated Agricultural Interventions: A Cross Sectional Study

Mengistu Fiseha Mekonnen, Derese Tamiru Desta, Zemenu Kerie Terefe

School of Nutrition, Food Science and Technology, College of Agriculture, Hawassa University, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Derese Tamiru Desta, School of Nutrition, Food Science and Technology, College of Agriculture, Hawassa University, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Improving nutrition requires many efforts through nutrition sensitive activities. Series of inter linked intervention activities in the Ethiopian humid tropics field sites has been conducted in the Western Oromia Region, Ethiopia. This study was conducted to determine the contribution of integrated agricultural farm interventions for dietary diversity of women and children. We employed comparative cross sectional study design among the women child pair participating and not participating in the integrated agricultural interventions in Diga and Jeldu districts of Western Oromia. A total of 345 mother child pairs were included for this study. SPSS version 20 software was used for data analyses. Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women and Child were computed and tested by Chi-square and Independent Sample t-test to check the differences among the group. The majorities of mothers were married and protestant religion followers. We found that mean dietary diversity was less than the recommended intake among mother child pairs. However, the percentages of recommended minimum dietary diversity consumption across the groups of mother-child pairs were found to be different. The dietary diversity score was higher among those mother child pair participated in the integrated agricultural farming interventions. Legumes, Vitamin A rich and other Fruits & Vegetables, and Eggs consumption were higher among the children from participated in the integrated farming intervention.Considering the findings of the current study, holistic agricultural interventions aiming at improving dietary diversity of the vulnerable groups in the community has to be strengthened.

Keywords: Children, Dietary diversity, Food Group, Integrated Farming, Women

Cite this paper: Mengistu Fiseha Mekonnen, Derese Tamiru Desta, Zemenu Kerie Terefe, Comparison of Dietary Diversity among Women-Child Pairs from Households Participated in Integrated Agricultural Interventions: A Cross Sectional Study, Food and Public Health, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20201001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Agriculture is the main occupation for developing countries including Ethiopia. Within this context targeted agricultural programmes and social safety nets have been playing a great role in lessening potentially negative effects of food and nutrition security of the globe at large. Mainly the programs and strategies do have effects through improving livelihoods, food security, diet quality, and women’s empowerment, and in attaining high coverage of nutritionally at-risk households and individuals [1]. Ensuring food and nutritional security of individuals and households in a sustainable manner requires systematic and holistic approaches [2,3]. In this regards, it is very important to understand the systems or approaches linking agricultural production and nutritional security in the emerging nations. The process connecting farming activities and nutritional outcomes involves more than just an increase in the quantity of food produced for subsistence consumption. For Instance there could be different pathways through which farm diversity potentially influences dietary diversity, and the magnitude and direction of the effect depends on a multitude of confounding factors. The most important lane could be by subsistence consumption of food products directly from the production [4]. A number of studies indicated that diversified farming practices could improve farmers’ health by improving nutritional profile of consumers [5-8]. However, less farm diversification where the people entirely depends on farming could result in the loss of dietary diversity [5]. On the other hand, the agricultural systems are linked with food and nutrition security. For example, market access could have a basic role as a factor linking farm production and household nutrition. Farmers participating in agricultural markets both to sell part of their harvest, and using the cash income they can afford to purchase diverse foods that improve dietary quality. Market access could help the farmers to produce specific food crop based on the demands of the market. This helps to increase farm income among the farming community. Beyond these household income and gender– control of women over farm revenues plays a crucial role in increasing dietary quality [2,6].Merely producing more food does not always ensure food security or improved nutrition. Agriculture interventions do not always contribute to positive nutritional outcomes. Recognition that growing more food is necessary but usually not sufficient to achieve good nutrition and health leads directly to hypothesis-building around what else might be required [9,10]. In these regards, with the existing integrated agricultural farm initiatives, the relationships between the agricultural systems or activities and nutritional outcomes are not well addressed in Ethiopia. A series of inter linked agricultural interventions in the Ethiopian humid tropics field sites has been initiated. The interventions were, intercropping of legumes with maize, row planting of wheat, combined with establishment of soil bunds to extend the growing season. Additionally, complementary activities on nutrition, gender, natural resource management and cropping multipurpose trees for human consumption has been done in the Western Oromia, Ethiopia [11]. However, still the researches done on the impact of these interventions on food and nutrition are limited. Therefore this study was aimed at exploring whether the integrated agriculture farm activities are really contributing for dietary diversity of mother and Under two (6-24months) children in the Western Oromia, Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Integrated Interventions

- The study was conducted in two different districts of Western Oromia, (Diga district, East Wollega and Jeldu district, East Showa zone). The first study district, Diga, is located at about 346 km away from Addis Ababa and 15 km from Nekemte town to the West Ethiopia. The area shares boundaries with West Wollega Zone in the West, Guto Gida Wereda in the East, Sasiga in the South and Leka Dulecha in the North direction. Mixed rain fed agriculture Maize based single cropping dominates in the areas. The major crops are Maize, Sorghum, Tef, Finger millet, Niger seed and Sesame and Livestock like Cattle, Sheep, and Poultry. In Arjo, one of the sub districts, an integrated farming activity has been practiced. The integrated farming activities were water and soil conservation, animal feed production.Crop rotation, adopting legumes and adopting crop’s like Orange Flesh Sweet Potato (OFSP), Quality Protein Maize (QPM) and improved variety of barley has been conducted. The second study district was Jeldu in the west Showa. The district is bordered on the south by Dendi, on the southwest by Ambo town, on the north by Ginde Beret, on the northeast by Meta Robi, and on the southeast by Ejere towns. This district has a similar agro ecological condition with Diga district which is humid tropic, growing almost similar crops and livestock’s [11]. In general in the study sites, series of linked interventions were initiated in 2014. These interventions involved intercropping of legumes with maize, row planting of wheat, combined with establishment of soil bunds to extend the growing season. Infiltration trenches were introduced into degraded grazing lands, which were integrated with over sowing of improved fodder. Sweet potato vines together with other biomass were conserved as silage to ensure proper utilization of the increased feed resources and to fill the seasonal feed gap. Additionally cross cutting issues like women empowerments has been also addressed [12,13].

2.2. Study Design and Population

- Comparative cross sectional study design was used among 345 mothers with their child pairs aged 6-23 months. A total of 173 respondents were from participated and 172 respondents from non participated households in the integrated farming interventions were drawn in the study sites. The study was conducted from November to December 2016.

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Techniques

- Epi-Info software was used to calculate the final sample size. Proportion of adequate household dietary diversity as 10% and 21% of inadequacy of household dietary diversity was considered as a control and exposed respectively in the Ethiopia highlands [14]. Confidence level of 95%, 80% power, 1:1 allocation ratio, and 10% non response rate were assumed. The final sample size was 345 mother_child pairs. The study areas were selected purposively following the integrated farming activities intervention in Ethiopian highlands. Simple random sampling technique was used to select mother-child pair. Firstly a household to household registration was conducted to identify household with mother-child pair. During the registration, exclusive code was given for each household with mother to child pair. Using the list of numbers a sampling frame was prepared and final respondents were selected using a lottery method. Lastly, the 345 samples were drawn from the total mother to child pairs in the sub-districts at the time of survey.

2.4. Data Collection Tools and Procedures

- A pre-tested, semi-structured and questionnaires were used to determine socio demographic, dietary diversity and household food security status. The questionnaires were initially prepared in English and translated to local language (Afan Oromo) and appropriate translation into local languages and adaptation of the food lists to reflect locally available foods were considered. Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD-W) was measured using the guideline published by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and USAID’s Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA). MDD-W was considered as a dichotomous indicator of whether or not women 15–49 years of age have consumed at least five out of ten defined food groups the previous day or night [15]. Whereas, the minimum dietary diversity for children, a measurement tool prepared for assessing infant and young child feeding practices Part 2 Measurement was used [16]. The diversity questionnaire consists of 7 groups of foods, which covers almost every food taken. In addition the questionnaire has a single question about any food or fast food consumed out of the house. One usual day in the week except holidays and weekends was selected. Data was collected from mothers/care givers who have one child in age 6 to 23 months from each household by direct interviewing. Food security status of households was determined by FANTA household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) guiding tool [17].

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

- The collected data were coded and entered in to Epi-Info version 3.5.1 and exported to SPSS Version 20 for analysis, standard deviations, and frequency distributions of variables were determined. Chi-square test was used to check the differences between the nominal variables and independent sample t-tests were computed. Significance was set at p < 0.05. household assets were considered to construct the wealth index via a Principal Components Analysis (PCA). Dietary diversity scores were calculated by summing the number of food groups consumed. Later the scores were compared among each group. A category of household food insecurity as food secure, mild, moderate and severe was made.

2.6. Ethical Consideration

- Approval of the research was given by Hawassa University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The nature of the study was fully explained to the respondent and oral consent was taken ahead of interview.

3. Results

3.1. Socio Demographic and Economic Characteristics

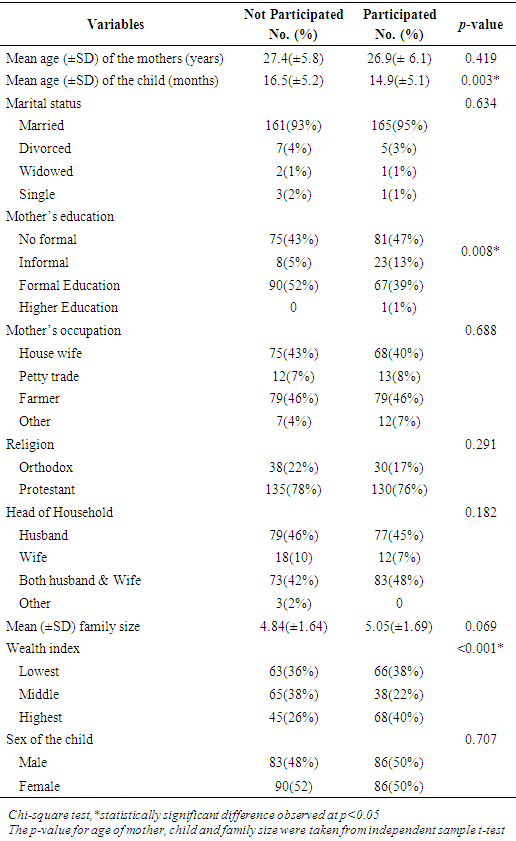

- In the current study, 345 women-child pairs were included. The majority (94.5%) of the respondents were married at the time of interview. Of the total respondents, protestant religion was the dominant group (76.8%). The mean age (±SD) of the mothers was 27.1±5.8 and 26.9.1± 6.1 years among the women participated in the integrated farming intervention and non-intervention sub districts, respectively. Most of the mothers (45%) in both groups did not attend formal education. Large mothers (46%) were farmers from each sub districts. The mean (±SD) family size of the households was 4.84(±1.64) in the households of women who did not participate in the integrated farming intervention and 5.05(±1.69) in the participated households. The mean (±SD) age (months) of the child from households not participated and participated households was 27.4(±5.8) and 26.9(± 6.1), respectively. Among socio-economic variables, chi square test reveals that mean age of the child, maternal educational status and wealth index showed statistically significant difference between the two groups being compared (P<0.05) (Table 1).

3.2. Household Food Security Status

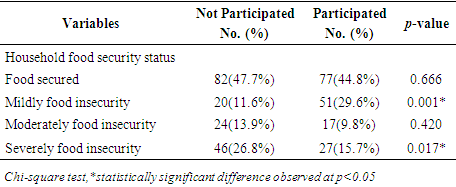

- Household food insecurity was assessed using FANTA household food insecurity access scale (2007). The finding implicates that 55.1% of the households in the intervention program and 44.9% of the intervention were food insecure which is statistically significant at P value of 0.05. Of the non-intervention households 20.7% of them were involved in productivity safety net program (PSNP) while 21.4% of the intervention households were part of the same program, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

|

3.3. Minimum Dietary Diversity of Mother-Child Pairs

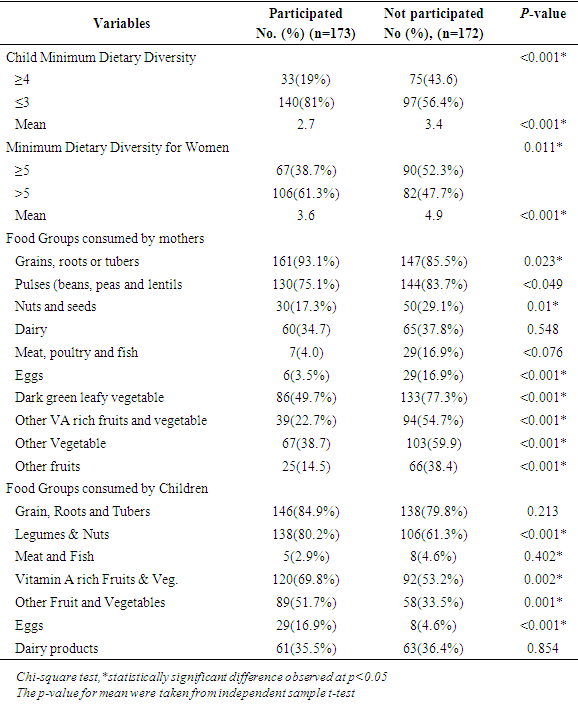

- Minimum dietary diversity for the children and women were computed. The percentage of children who consumed the recommended minimum dietary diversity among the total children was by 33.1%. Whereas among the women, only 45.5% of consumed the recommended minimum dietary diversity. Categorically, the child minimum dietary diversity score was found to be significantly different (p<0.05) among those from households participated in the integrated farming activities. Additionally, significant difference (p<0.05) in minimum dietary diversity of women was documented (Table 3).

3.4. Composition of the Food Groups Consumed by Mother-Child Pairs

- The details of various types of food groups consumed by the mother and children are described in table 3. Grains, Roots and Tubers are the food group mainly consumed by the women and children. Legumes and nuts were the second major food type consumed by the women and children in the study area. Animal source foods (Meat, Poultry, Fish and Eggs) are the least food item consumed by the women. Whereas, Meat and fish food group was the least food group consumed by the children in the study area during the time of interview. Comparison of food groups consumed by women and children who did participate and not participate in the integrated farming intervention is more crucial to know about which food group is differently consumed. In the current study, except the dairy food group, the other food groups were differently consumed by the women from households participated and not participated in the integrated farming interventions (p<0.05). Women from the households participated in the integrated farming interventions had better consumption of different food groups compared with their counterparts. Among the under two children, legumes, Vitamin A rich and other Fruits & Vegetables, and Eggs were consumed significantly different (p<0.05). The children from households participated in the integrated farm interventions had better consumption of the aforementioned types of food groups (Table 3).

|

4. Discussions

- Stepping up of progress in nutrition requires many efforts through nutrition sensitive activities. The programmes has to address the underlying determinants of malnutrition [1&7]. Increasing food production alone, whilst ignoring distributional issues, was not sufficient to eradicate malnutrition, unless the poorest were given access to food. Enhancing the diversity of agricultural production systems is increasingly recognized as a potential means to sustainably provide diversified food for rural communities in developing countries, hence ensuring their nutritional security [18]. In this regards, evidences are very crucial in contributing through identifying the linkages between the integrated agricultural interventions and nutrition despite it is still weak [7]. The current study substantiate that the minimum dietary diversity of women and children was found to be significantly higher (p<0.001) among those who are from the household participated in the integrated farming interventions. This proves that holistic agriculture interventions can increase dietary diversity of the vulnerable groups in the community. Different studies confirm that nutrition sensitive interventions and programs have a positive association with an increased dietary diversity and other nutrition indicators [3,7,19,20]. In the study area, among the under two children, legumes, Vitamin A rich and other Fruits & Vegetables, and Eggs were consumed significantly different (p<0.05). The children from households participated in the integrated farm interventions had higher consumption of the aforementioned types of food groups. Grains, Roots and Tubers are the food group dominant and mainly consumed by the women and children. This is comparable with the results from the studies done before in Ethiopia similar to the other developing countries [21-23]. Legumes and nuts were the second major food type consumed by the women and children in the study area. Animal source foods (Meat, Poultry, Fish and Eggs) are the least food item consumed by the mother-child pairs. This finding was supported by other reseraches done in the Northern Ethiopia [19,21,23]. Similar to the other findings, the current study showed that animal source food consumption is still low. Studies supports that in Ethiopia due to different predictors the animal source food consumption is very low at individual and household level [21,22,24].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Improving nutrition requires many efforts through nutrition sensitive activities. With these regards inter linked intervention activities in the Ethiopian humid tropics field sites has been conducted. Integrated agricultural interventions activities such as intercropping, row planting of wheat, combined with establishment of soil bunds to extend the growing season has been done in the study area. It was found that the percentage of children who consume the recommended minimum dietary diversity among the total children was 33.1% and 45.5% among the mothers. The women and child minimum dietary diversity score was found to be higher among those from households participated in the integrated farming activities. Legumes, Vitamin A rich and other Fruits & Vegetables, and Eggs consumption was higher among the children. Thus holistic agricultural interventions have to be strengthened to improve dietary diversity and other nutrition indicators of the vulnerable groups in the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors acknowledge the data collectors and respondents participated in the present study. We are also grateful for the School of Nutrition, Food Science and Technology, Hawassa University for supports given during the data collection processes. We have also special thanks to ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute, Addis Ababa) for overall financial supports and Mr. Zelalem Lema and Dr. Melkamu Derseh for their valuable feedbacks and guidance in all over works during data collection.

Funding

- The present study was funded by The Western Ethiopia Humid tropics R4D platform research program based at International Livestock Research Institute, Addis Ababa. The funder does not participate in data collection, analysis and interpretation.

References

| [1] | Ruel MT, Alderman H. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet. 2013; 382(9891): 536-551. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60843-0. |

| [2] | Khoury CK, Bjorkman AD, Dempewolf H, Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111(11): 4001-4006. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313490111. |

| [3] | Sibhatu KT, Krishna V V., Qaim M. Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015; 112(34): 10657-10662. doi:10.1073/pnas.1510982112. |

| [4] | Johnston D, Stevano S, Malapit HJ, Hull E, Kadiyala S. Review: Time Use as an Explanation for the Agri-Nutrition Disconnect: Evidence from Rural Areas in Low and Middle-Income Countries. 2018; 76 (February): 8-18. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.12.011. |

| [5] | Remans R, Flynn DFB, DeClerck F, et al. Assessing nutritional diversity of cropping systems in African villages. PLoS One. 2011; 6(6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021235. |

| [6] | Ickowitz A, Powell B, Rowland D, Jones A, Sunderland T. Agricultural intensification, dietary diversity, and markets in the global food security narrative. Glob Food Sec. 2019; 20 (February 2018):9-16. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2018.11.002. |

| [7] | Ruel MT, Quisumbing AR, Balagamwala M. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: What have we learned so far? Glob Food Sec. 2018; 17 (September 2017): 128-153. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2018.01.002. |

| [8] | Guzman LEP, Zamora OB, Bernardo DFH. Diversified and Integrated Farming Systems (DIFS): Philippine Experiences for Improved Livelihood and Nutrition. 2015; 33: 19-33. |

| [9] | Johnston D, Stevano S, Malapit HJ, Hull E, Kadiyala S. Review: Time Use as an Explanation for the Agri-Nutrition Disconnect: Evidence from Rural Areas in Low and Middle-Income Countries. Food Policy. 2018; 76 (January 2016):8-18. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.12.011. |

| [10] | Hodge J, Herforth A, Gillespie S, Beyero M, Wagah M, Semakula R. Is there an enabling environment for nutrition-sensitive agriculture in East Africa? Stakeholder perspectives from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. Food Nutr Bull. 2015; 36(4): 503-519. doi:10.1177/0379572115611289. |

| [11] | Bezabih Emama HM and SM. A situational analysis of agricultural production and marketing, and natural resource management systems in the Ethiopian highlands. 2015; (March 2015). https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/73059/PR__ethiopia_analysis.pdf?sequence=5. |

| [12] | Lema Z, Endeshaw T. Western Ethiopia Humidtropics Research for Development (R4D) Platform Launch Meeting Note February 5, 2015. 2015. |

| [13] | Mume M., Lema Z. Report of the Humidtropics western Ethiopia research for development platform first field visit in Jeldu Wereda and second meeting in Ambo University. 2015; (November). |

| [14] | Fofanah M, Lema Z. Agricultural pathways to improved nutrition in the Ethiopian highlands: dietary practices Key messages. 2016; (September): 1-2. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/77374. |

| [15] | FAO and USAID’s Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA) managed by F 360. Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women- A Guide to Measurement. 2016. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5486e.pdf. |

| [16] | World Heath Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. 2010. |

| [17] | Coates J, Bilinsky P, Coates J. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide VERSION 3 Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide VERSION 3. 2007; (August). |

| [18] | Khoury CK, Bjorkman AD, Dempewolf H, Ramirez-villegas J, Guarino L. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313490111. |

| [19] | Krishna V. Farm Production Diversity and Dietary Diversity in Developing Countries. 2015:10657-10662. |

| [20] | Saaka M, Osman SM, Hoeschle-Zeledon I. Relationship between agricultural biodiversity and dietary diversity of children aged 6-36 months in rural areas of Northern Ghana. Food Nutr Res. 2017; 61(1): 1391668. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1391668. |

| [21] | Kahsay A, Mulugeta A, Seid O. Nutritional status of children (6-59 months) from food secure and food insecure households in rural communities of Saesie Tsaeda-Emba District, Tigray, North Ethiopia: Comparative study. 2015; 4(1): 51-65. doi:10.11648/j.ijnfs.20150401.18. |

| [22] | Workicho A, Belachew T, Feyissa GT, et al. Household dietary diversity and Animal Source Food consumption in Ethiopia: Evidence from the 2011 Welfare Monitoring Survey. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16(1): 1-11. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3861-8. |

| [23] | Temesgen H, Yeneabat T, Teshome M. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Sinan Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2018; 4(1): 1-8. doi:10.1186/s40795-018-0214-2. |

| [24] | Sibhatu KT, Qaim M. Review: Meta-analysis of the association between production diversity, diets, and nutrition in smallholder farm households. 2018; 77(April): 1-18. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.04.013. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML