-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2019; 9(4): 119-124

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20190904.03

Socio-cultural Determinants of Food Security and Consumption Patterns in Kisumu, Kenya

Fredrick Omondi Owino

School of Spatial Planning and Natural Resource Management, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Fredrick Omondi Owino, School of Spatial Planning and Natural Resource Management, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Food security is an important measure of well-being of a household or community. It takes into consideration three dimensions namely availability, access and utilization. Even though it may not contain all dimensions of poverty, the inability of these households or communities to obtain access to enough food for a productive healthy life is an important component of their poverty. People from diverse backgrounds eat different types of food so as to retain their cultural identity. These communities living in Kisumu are defined by their own food culture. This study looked at production, distribution and storage of food among the communities living in Kisumu. It also examined the food habits, practices and beliefs associated with the households living in Kisumu. The research employed both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection. Content analysis was also used in the study. The research revealed that there is a food culture which has rich cultural practices which defines the community. At the same time, different cultures interact with one another and thus interfering with some of these traditional practices and beliefs.

Keywords: Food Security, Socio-cultural, Determinants, Nutrition

Cite this paper: Fredrick Omondi Owino, Socio-cultural Determinants of Food Security and Consumption Patterns in Kisumu, Kenya, Food and Public Health, Vol. 9 No. 4, 2019, pp. 119-124. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20190904.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Kenya Vision 2030 and its second Medium-Term Plan (MTP II) 2013-2017 outlines agriculture as a key driver of an anticipated 10 per cent annual economic growth. The Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation emphasized that sustained agricultural growth is important in attaining the targets of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2 as well as facilitating the attainment of the other SDGs. According to the Towards Zero Strategic Review which takes stock of the current status and trends in food, nutrition and agriculture in Kenya, food and nutrition insecurity is one of the major challenges currently affecting development in Kenya and is closely linked to the high level of poverty in the country in general and Kisumu city in particular (GoK, 2018). Food security is defined by the World Bank (1986) as ‘access by all people at all times to enough food for an active healthy life’. The essential elements of food security were availability of food and the ability to acquire it. A more detailed definition used at the World Food Summit was ‘all people at all times having physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (FAO, 1996). Food security in brief means ‘access to food for a healthy life by all people at all times’ (Barraclough, 1996; Mwale, 1998). Food insecurity has been a global problem affecting much of the third world countries. Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda are especially in a region prone to debilitating and widespread effects of hunger and famine. The Lake Victoria basin is particularly characterized by entrenched poverty, recurrent droughts, crop failures and environmental degradation. These conditions are partly caused by declining land productivity, soil degradation, desertification, loss of biodiversity, livestock and crop diseases, declining fisheries, poor development and trade policies, among other problems. Kisumu City currently has no policy on agricultural production, harvesting, and storage (Hayombe, Owino and Otiende, 2019). As a result, it has become difficult to produce sufficient food, trapping people in a vicious downward cycle of food insecurity. Paradoxically, many of the local communities living around Lake Victoria whose main economic activity has been fishing (Owino, 2016) are among the poorest and most food insecure. Fishing as a resource has been declining over the years due to population and environmental pressures thus there is a need for alternative livelihood sources (Owino, Hayombe & Agong’, 2014).

2. Method

- The study employed both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection. Desktop research approach entailed an analysis of published literature. Content analysis was also used to draw general statements. Multistage sampling was used to randomly come up with 841 households to be interviewed. This sample size was based on the population of Kisumu City, which was 409,928 persons, with an average household size of 4.3 persons according to the 2009 population census. (KNBS/SID, 2013). The number of households was thus estimated to be 95,332. The 841 respondents were distributed proportionately across the city. This was done by dividing the city into three sectors. These were the western, eastern, southern and areas of residence which were classified as high, middle and low income and peri-urban were selected in each of the sectors. The households were selected in each residential area according to the population density of the neighbourhood. Sixty per cent of the respondents were selected from informal settlements because 60% of the population in Kisumu city resides in these settlements (UN-Habitat, 2005).

3. Results and Discussions

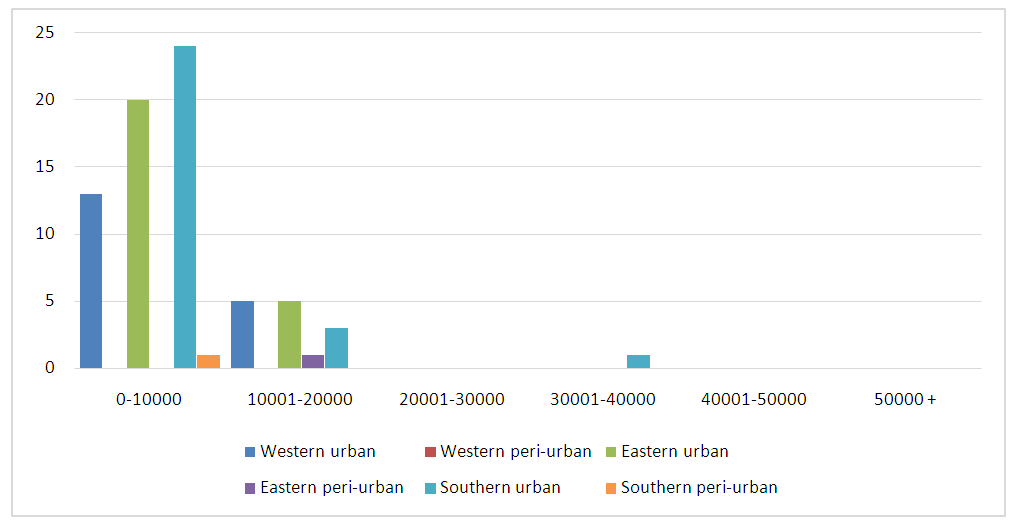

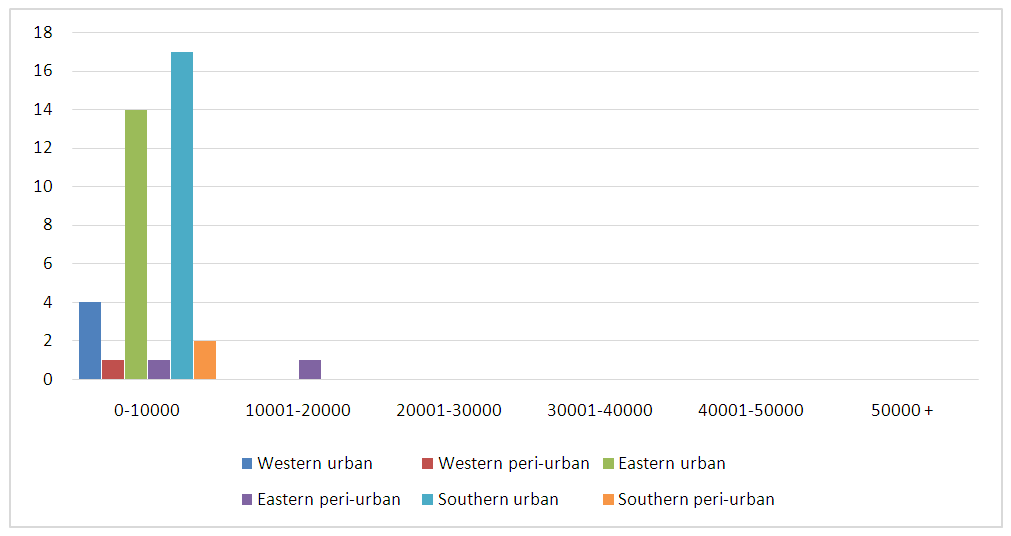

- Cultural practicesKisumu is a cosmopolitan city catering to different tastes, cultures and palates. The city is comprised of many tribes namely the Luo, Luhya, Kisii, Kikuyu and Kalenjin among others. Culture to a greater extent influences people to participate in food production, marketing and distribution. Different tribes for example the Luo's have preferences to some food e.g. what to give to children, women and men. Their culture also dictates what a person is supposed to eat. During festivals such as weddings and funerals, people usually serve different meals. For instance, when an in-law comes to visit, then a chicken has to be slaughtered. Animals such as sheep, goats, chicken and cows are used as food and for paying bride price. The Luo and Bantu communities for instance dictates that young women should not eat meat from sheep. This restriction was nonetheless not put on the elderly women as noted by Evans and Mara (2012). Production systems are also dictated by cultural requirements. Food production among communities living in Kisumu has been a collective responsibility involving all members of the family. In the past, land was communally owned and as a result, all family members had to participate in cultivation. Among the Luo community, cultivation was also carried out based on seniority of the family members. This seniority was with respect to the wives in the case of polygamous families. The first wife had to cultivate first then followed by the second. This process also applied during harvesting of food. The household head for example had to eat maize first before any other member of the family. This ensured that there would be enough food for all members of the family during harvesting time. There were also granaries for storage of food for future use and this ensured food security for the household.Culture is dynamic and has been changing over time. The idea of growing food in the urban areas has been dictated by population dynamics. Agriculture for example has been practiced in urban areas to provide food security to protect against sudden food shortages as a result of urban growth and drought (Urban Design Lab, 2012). For the poor in society, food security is the main motivation for farming, though many sell their produce to buy basic household needs or subsidize their income. Hayombe, et. al. (2019) established that less than 15% of Kisumu City residents grow some of their own food. The production of vegetables and grains that does take place in Kisumu City is largely for subsistence purposes and involves minimal storage or processing. Observations from the field also indicate that commercial production of indigenous vegetables is increasing to meet the increased food demand of the city so as to curb food insecurity.Land tenureLand ownership in Kisumu is both freehold and leasehold. This means that control and management of land is according to ownership and tenure system and this affects productivity. Land tenure, therefore, has effect on food production. The amount and type of food will depend on whether the land is communally owned or belongs to an individual. Land ownership is also associated with status of an individual in society. Those who do not own land are deemed to be poor. Poor people typically do not have the financial means to produce enough food to sell, and usually the price of grain is too low to buy alternative foods. In any case, the main beneficiary from trade is not usually poor farmers but middlemen, who have the advantage of better information about market demand and prices. Land tenure also determines the socio-economic status of urban and rural households. This is more likely to influence food access and the nutritional status of children in urban and rural communities. This is because the main source of food for households which do not own land (mainly in urban areas) is through purchase compared to rural areas where food is more often home produced (Zuma & Ochola, 2010). Limited access to land ownership and other valuable assets by women contributes to list of factors responsible for food insecurity (Wambua, Omoke & Mutua (2014).Food production and marketingKenya produces a lot of food. It is just that a lot of it get wasted and does not get to those who need it. The county governments should be able to support their people in dealing with the problem of food waste. There is need to help the farmers eliminate post harvest losses to bridge the gap from both ends that is production and accessibility. Kisumu's food system relies heavily on the regional and city transport systems, and the linkage between the city, processing sites and production sources of food (Opiyo & Ogindo, 2019). Promoting safe food production and distribution has faced many challenges in Kisumu especially from those who are worried about the potential health risks of producing and distributing food within an urban area. The capacity to produce and store food is still critical, though not sufficient. This is to ensure food security. The access to food which is determined by the ability to buy or acquire food, control productive resources, or exchange other goods and services for food is another important index of food security. Food quantities which can be accessed must be sufficient enough to meet national, regional or household needs, as well as fulfilling nutritional needs of adequate energy, protein and micronutrients. In the past, the global strategies to solve food problems have mainly aimed at increasing agricultural production at both the household and national levels and ensuring that a portion of the produced food was stored to last through to the next harvest (Brown and Kane, 1994). However, these strategies have not been successful in alleviating food problems especially in the third world, mostly because of declining land sizes, stagnated farming technology, poor infrastructure, the demand for cash money and ever-expanding population. More recently, there have been attempts to change focus, and place less emphasis on self-sufficiency. Instead, trade has come to be regarded as a more important tool of tackling food insecurity.Women and men have different roles e.g. selling of food is more of female's work. Preparation of food involves who buys and who sells. Men are fewer in the food system but they have the power. Culture dictates that it is a male dominated society. In most cases, men are the officials and are given the role of making decisions and allocating space for selling of food. It also dictates who owns the means of production, marketing and deciding on what to be cooked. Food preference thus is a factor of food security.Psychological preferencesFood plays a major role in the culture, traditions and daily life of communities living in Kisumu. Weddings, funerals, and religious celebrations which are important events are always accompanied by food specifically prepared for the occasion. Consumption of traditional food is largely associated with poverty and as a consequence, as people move to the city, they change their diet to a typical westernized diet with a high fat content and low carbohydrate intake (Bourne, 1996). This study found that different communities in Kisumu associate meat with high socio-economic standing and therefore try to consume it on a daily basis. These findings confirm those of Wong and Valencia (1984) who examined a relationship between household income, level and expense and consumption of food in urban marginal areas of Mexico. Wong and Valencia (1984) found a marked tendency to increase consumption of high protein foods as family income increased. This trend was also reported by Belk (2000) who observed that new elite of Zimbabwe increased the frequency of meat consumption, as well as the quantity, but not the quality of their diet. It is a tendency that when people move to the city, they abandon traditional foods, which include grains, root plant, lentils, greens and edible insects such as termites, crickets, grasshoppers and lake flies. They usually adopt foods that are associated with status, such as meat, and fast foods. They perceive consumption of foods such as corn, beans, greens, and root plants as associated with poverty. This study confirms that once people get settled in the city, their expenses increase, leaving them with little money for food. They, thus, resort to cheap unhealthy food which is readily accessible in their environment. This has also led to high level of malnutrition mainly among children in the region. Rural-urban linkagePeople exchange and share food at will. This can be done between relatives and between urban and rural communities. There is also the issue of the culture of care giving to the young and widows. In most cases, when a child visits the grandmother or aunt in the rural areas, then they are given chicken to carry along with then from wherever they have come from as a sign of appreciation. On the other hand, those in the urban areas remit cash to their relatives in the rural areas (Figure 1). This strengthens the ties between relatives living in the rural and those in the urban areas.

| Figure 1. Household's expenditure on cash remittances to rural areas as established via 2017 field survey |

| Figure 2. Household's expenditure on gifts and family support as established via 2017 field survey |

4. Conclusions

- There are a number of factors which have been found to determine the dietary habits of people in Kisumu city. Food consumption pattern has changed as a result of sudden increase in income levels. Socio cultural factors such as religion, beliefs, food preferences, gender discrimination, education and women's employment have had a noticeable influence on food consumption patterns in Kisumu city. Mass media, especially televised food advertisements, play an important role in modifying the dietary habits. This study illustrates the strong social and cultural determinants of food security and eating patterns in this population. Information in this paper is a useful starting point for developing suitable interventions in this type of population. The issue of food insecurity is multi-dimensional. It is arising from a number of cultural causes that put constraints to food availability or limits local people’s access to it. Food forms part of any community's cultural life. They engage collectively in rituals such as are observed during crop production and storage for subsistence purposes. At times, it is observed that food crops are sold for monetary returns in market places as opposed to subsistence.

5. Recommendations

- It is recommended that the Kisumu city administration should come up with an elaborate plan on how to preserve the diverse food cultures of the communities who are inhabitants of the city. This should take cognizance of the socio-cultural, economic and political inhabitants of Kisumu as well as the neighbouring communities. This could be done by holding annual cultural festivals organized by the County Government in conjunction with other partners such as the Kisumu Local Interaction Platform (KLIP) which has been in the forefront in organizing such events. In order to address the issue of food insecurity, there is need to strengthen cultural values and beliefs on issues to do with food preservation and farming practices. These practices include the use of farm yard manure and leaving adequate land for farming as opposed to subdividing land into uneconomical sizes. This can be done through formulation of sectoral policies for example to regulate the use agricultural.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I extend my gratitude to MISTRA Urban Futures (MUF), Kisumu Local Interaction Platform (KLIP) and Consuming Urban Poverty Project for the funding and provision of data used in undertaking this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML