-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2019; 9(1): 21-31

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20190901.04

Optimum Utilization of Antenatal Care (ANC 4) Service is Still a Long Way Down the Road in Bangladesh: Analysis of Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey Data

Md. Ruhul Kabir1, Homayra Islam2

1Department of Food Technology and Nutrition Science (FTNS), Noakhali Science and Technology University (NSTU), Noakhali, Bangladesh. Previous affiliation: Umea International School of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umea University, Sweden

2Office of the Deputy Commissioner, Noakhali, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangaldesh

Correspondence to: Md. Ruhul Kabir, Department of Food Technology and Nutrition Science (FTNS), Noakhali Science and Technology University (NSTU), Noakhali, Bangladesh. Previous affiliation: Umea International School of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umea University, Sweden.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

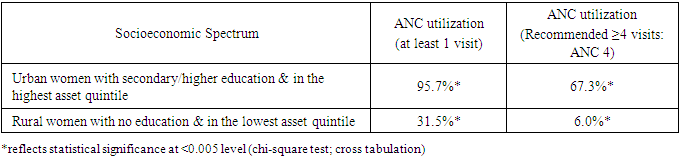

Background: The antenatal care (ANC), care during pregnancy can act as a bridge between the women and her family with the formal health care system. Hence, failure to make optimum number (recommended by WHO) of visits (4 times) to health care professionals (ANC 4) can breaks that critical link and that could be catastrophic for the survival of mothers and her babies. Despite of growing importance towards maternal health care service utilization in Bangladesh, the ANC 4 utilization is still very meager. This paper examined the pattern of utilization of recommended 4 antenatal care visits and how different determinants affect toward low utilization. The paper also attempted to see- how the ANC 4 utilization varies across different socioeconomic groups. Methods: The 2011 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey data (BDHS) was used and the study considered 8,753 ever married women aged 15-49 years who had at least one child in the last five years preceding the survey. Along with descriptive statistics and measured association by using χ2-test, multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the association between potential determinants and ANC 4 service utilization. The study also attempts to answer the differences in ANC 4 utilization between the women of two opposite socioeconomic strata. Results: Only 26.4% women made recommended 4 antenatal care visits and significantly associated determinants of ANC 4 utilization were place of residence, household wealth index, mother’s education, partners’ education and occupation, mother’s age at conception, birth order and family size; some other factors have shown varied significance across groups. The rural-urban, poorest-richest and educated-uneducated differentials unveiled big differences in the ANC 4 utilization which needs special attention to be addressed. The differences between the mothers of two opposite socioeconomic strata revealed that more than 67% of the urban, richest and highly educated mothers received ANC 4; whereas the figure was only 6.0% for the mothers who lived in rural areas, were poorest and did not have formal education. Conclusion: The burden of maternal morbidity and mortality in Bangladesh remains a major concern and progress should be made in addressing socio-demographic factors so that recommended number of ANC visits can be possible.

Keywords: Antenatal care (ANC), Determinants, Maternal health care service utilization, Bangladesh

Cite this paper: Md. Ruhul Kabir, Homayra Islam, Optimum Utilization of Antenatal Care (ANC 4) Service is Still a Long Way Down the Road in Bangladesh: Analysis of Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey Data, Food and Public Health, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 21-31. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20190901.04.

1. Introduction

- Antenatal care (ANC) identifies and manages pregnancy related complications by providing a range of services to the pregnant women that includes early detection of risks during pregnancy, prevention and treatment of labor complications. It also provides behavioral modification or adjustments messages to the women and her family as well as about emergency preparedness to ensure safe and uncomplicated passage of delivery [1-4]. The utilization of ANC services may lead to the use of safe delivery care in appropriate health facility and can ensure the presence of skilled health professional during labor, delivery and post delivery periods [2, 5-9].The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least 4 ANC visits for uncomplicated cases [10-14], and the first visit to receive ANC services should be between 8-12 weeks of gestation which includes confirmation of pregnancy and expected date of delivery (EDD), women requiring basic ANC (4 visits only) or more specialized care, screening, treating and giving preventive measures followed by development of birth plan and so on. The second visit (24-24 weeks) involves assessment of maternal and fetal well-being followed by identification and treatment of maternal health conditions requires attentions along with advises and counsel. The third (32 weeks) and fourth (36-38 weeks) visits follows the same procedures unless any complications arises [11-12]. The provision of essential interventions provided by focused ANC 4 also pledges identification and management of obstetric complications such as preeclampsia, tetanus toxoid immunization, malaria prevention and other infections such as HIV, syphilis and different sexually transmitted infections [15-21]. According to a systematic review, between a third and a half of maternal deaths occurs due to causes like maternal hypertension (pre-ecclampsia and ecclampsia) and antepartum hemorrhage which have been found directly associated with inadequate care during pregnancy [16].In developing countries several socioeconomic and demographic factors affects the utilization of ANC 4 services which includes women’s age at conception, maternal education, husband’s education and occupation, birth order of the child, size of the family, religion, household wealth condition as well as other important determinants such as availability of existing health service facilities, cost and quality of services, accessibility of health services to the women of reproductive, knowledge of visiting skilled health professionals, history of obstetric complications, cultural and religious barriers, superstitions, access to media, women’s decision making capabilities [21-27]. According to some recent studies conducted in Bangladesh, India and Nepal revealed that partner’s education in addition to women education influenced ANC utilization by a great deal. Kavitha N (2015) and A. S. M. Shahabuddin et al (2015) put emphasis on young age of the mother and mother’s rural area of residence as risk factors for low utilization of ANC services [28-33]. Bangladesh has achieved astounding progress in the area of poverty reduction, gender parity in education, immunization coverage as well as considerable decrease in communicable diseases incidence despite of sustaining a weak health care system and low GDP distribution on improving health care [34-36]. Though remarkable progress has been made but still it needs to go a long way concerning maternal mortality ratio which remains one of the highest in the world. The lifetime risk of maternal death in Bangladesh was 220 per 100,000 in 2015 according to the World Bank and the maternal mortality ratio was 176. Pregnant women receiving antenatal care at least once by skilled health personnel was 53% in 2013 [34].To tackle these huge burdens, the Government of Bangladesh has developed Health, Population and Nutrition Sector Development Program 2011-2016 and after that another five year plan which emphasized more on nutrition services from community to national level and included an operational plan for mainstreaming and scaling up nutrition services through National Nutrition Services (NNS). The program focused more on the reduction of maternal mortality ratio by expanding the access and quality of maternal and child health care services (MCHS) and key services includes providing antennal care, assisted delivery , postnatal care and neonatal child health care [37]. However, despite of Government and other development organizations plans and efforts the utilization of maternal health care services remains low and the situation seems more aggravated when it concerned with optimum number of visits a mother should make to skilled health care professionals during her pregnancy period. According to Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey (BDHS), 79% of women received ANC services from any provider and among them 64% of women received ANC services from a medically trained provider, whereas, only 31.1% of them made recommended number of visits (ANC 4) which should be concerning to say the least considering the WHO recommendation of at least four visits during pregnancy period. The reports also revealed that older women with high birth order and who live in rural areas are less prone to receive ANC than other women. Mother’s education, household wealth and some other socio-demographic factors also influences the proportion of seeking ANC services among pregnant women [38]. According to the following studies- Mahejabin et al (2016) and Shahjahan et al (2017) - conducted in rural areas of Bangladesh revealed mothers education as an important significant factor for the optimum utilization of antenatal care [28, 29]. Shahab Uddin Howlader et al. (2018) also pointed out the importance of education (men and women) for seeking medical health care during pregnancy along with some other socio-economic factors [30].This study, therefore, aims to examine the pattern of ANC utilization and how different socioeconomic and demographic factors affect the utilization of optimum ANC services (ANC 4) in Bangladesh. The paper also attempts to answer how the utilization of ANC 4 services differs at opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum (women who lived in rural areas with no formal education and belonged in the poorest household wealth group against women who lived in urban areas, highly educated and belonged in the richest wealth group) which may signify the differences of ANC service utilization of two social groups of women. The results will provide serious evidence and insight to policy makers and responsible authorities to address the determinants affecting the utilization of optimum ANC services.

2. Methods

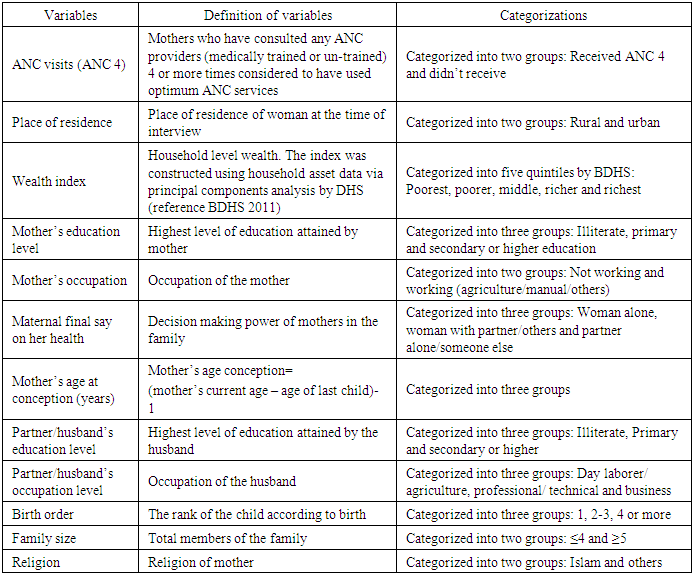

- This study was based on the 2011 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS). The BDHS designed to provide information on demographic status, family planning, maternal and children’s health and also pledge decision makers and program managers with the information necessary to plan, monitor and evaluate population, health and nutrition programs [39]. The sampling procedure of BDHS can be found in Measure DHS Guide [40].The present study only considered information from ever married women aged 15-49 years who had at least one child in the last five years preceding the survey and a total of 8,753 women fulfilled study eligibility criteria and the final dataset consists information about mother’s background characteristics: age at last conception, education, religion, occupation, maternal final say on health care service utilization, birth order, family size; husbands background characteristics: education, occupation; socioeconomic factors: area of residence; household factors: wealth status; community data on maternal health care utilization: ANC service utilization.Variables:As the primary focus of the study was to determine the effects of socioeconomic and demographic factors on the utilization of optimum ANC services (ANC 4), therefore, the analyses emphasized on whether women had received 4 or more ANC consultations (ANC 4) or not. Therefore, the outcome variable was ANC 4 utilization (ANC 4).The paper also attempts to answer how the utilization of ANC services differs at opposite ends of the socioeconomic strata by creating two opposite spectrum variables - women who were living in rural areas, with no formal education and belonged in the poorest household wealth quintile versus women who were living in urban areas, with secondary or higher education and belonged in the richest household wealth quintile.The study tried to follow the theoretical framework of behavioral model proposed by Andersen [41] and the model describes how different determinants associated with health care service utilization affects individual health seeking behaviors and factors should be grouped according to their hierarchical order of direct effect [41-43]. The present study tried to maintain the hierarchical order (distal to proximal factors) by considering community level characteristics of women followed by household characteristics and then individual level characterization as women are nested within households which in turn nested within communities. Woman’s place of residence was considered as community level external environmental factor and household wealth index & family size marked as household level characteristics. The individual level characterization of women were: women age at conception, education and occupation of women and their husband, birth order of the child, religion and women’s decision making capabilities on her own health care (Table 1). The study did not consider factors like quality and expense of the health care, attitude of the providers, cultural barriers, distance of providers and contribution of mass media etc. The present study tried to include important determinants concerning their association with the ANC 4 based on the evidences collected from existing literature and availability of information in the DHS dataset.

|

3. Results

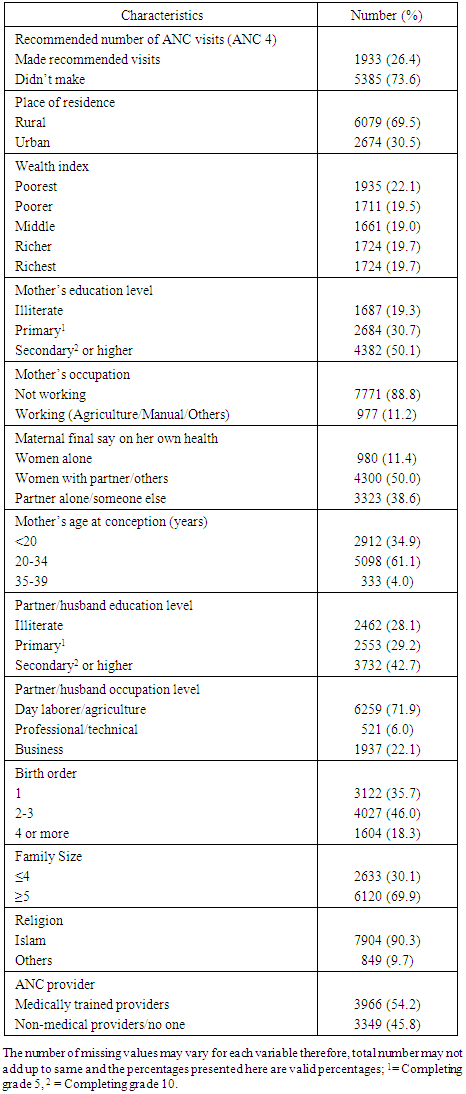

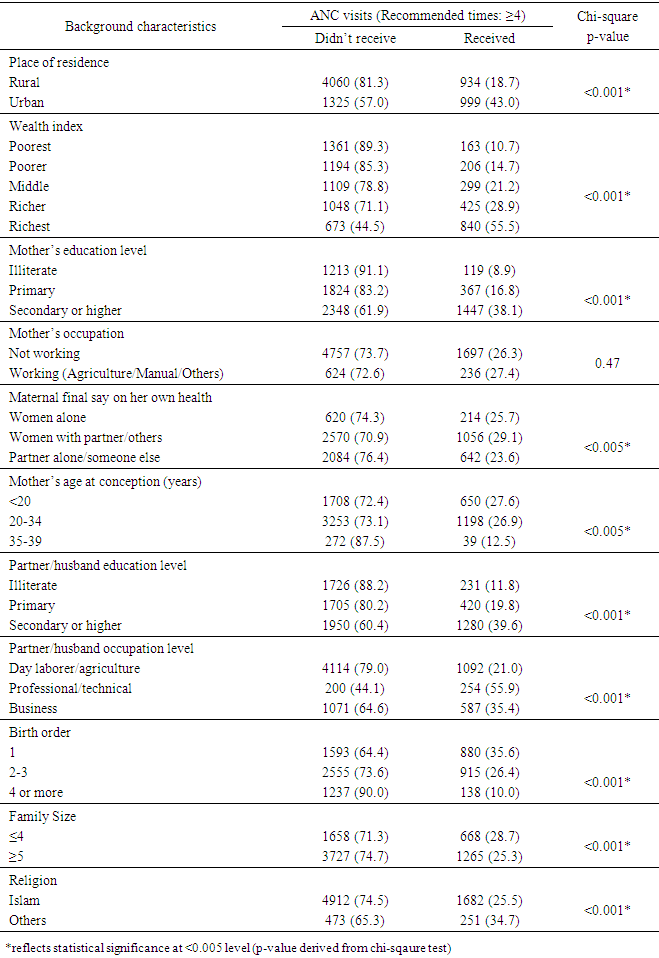

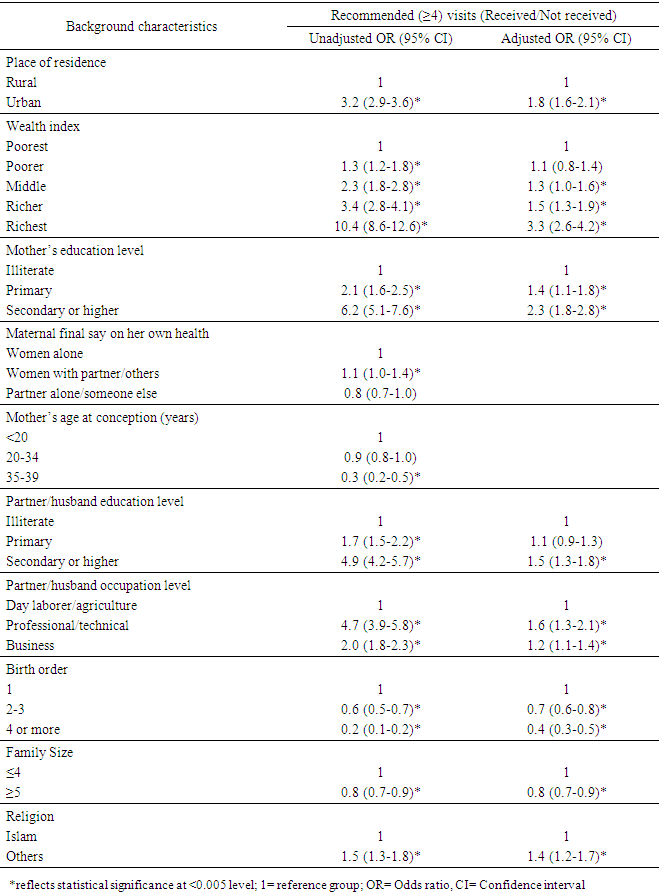

- According to the study findings, only 26.4% of the women visited recommended number (4 or more) of times for ANC services and the rest either made less visits or did not visit at all. Around 20% of the women were illiterate, in contrast, more than 50% of the women had secondary or higher education, however, only 11.2% of them were engaged in professional activities (agriculture/manual/others) and the rest was not involved professionally in economical activities. The result unveiled that only 11.4% of the women took decisions about her own health care and more than 38% of women did not take part in decision making at all about her health care where partner alone or someone else in the family took most of the decisions. Most of the women were in the child bearing age of 20-34 years, around 70% of them were living in rural areas and more than 90% of them were Muslims.Furthermore, more than 42% of the partner/husband had secondary or higher education and around 72% of them were engaged in day labor/agriculture activities for their living. However, if we consider household wealth status, the distribution of women from poorest quintile to richest remains almost around 20% for each quintile which means more than 40% (22.1 + 19.5) of the women were living in the poorest and poorer wealth quintile group. The result also revealed that more than 35% of the women were having their first child and around 70% of the women were living in a family with more than 5 members. Moreover, utilization of ANC services (ANC 4) according to background characteristics (Table 3) revealed that only 8.9% of illiterate women recommended number of visits for receiving ANC services, whereas, the figure was 38.1% for women who had secondary or higher education. The significant statistical association of mother’s education and ANC 4 showed that the percentages of women visiting ANC providers increased with the improvement of mother’s education. Partner/husbands educational and their occupational status had also large effect on recommended number of ANC visits as around 40% and 56% of women visited recommended times when her husband had secondary or higher education and had professional/technical job respectively while the percentages were much lower when husband had no formal education or had only primary education and had other low category manual jobs.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The study has exhibited important information regarding the associated factors which influenced the utilization of ANC 4 services in Bangladesh. Women’s place of residence were found strongly positively associated with utilization of optimum ANC 4 services which points out the rural-urban differentials of utilizing ANC 4 services by the women. The proportion of women living in urban areas utilized ANC 4 more than twice than their rural counterparts. Though the proportion of women attending ANC 4 was still less than 50% for urban women, however, the difference of accessing and utilizing the ANC 4 services cannot be overlooked. Several studies in different countries have suggested that the problem of accessing the service and distance as well as time to the nearest health faculties influence health service utilization [44-47]. The rural-urban differentials in utilizing ANC 4 pointed out that accessing health care services as well as distribution of health personnel and utilities should improve in rural areas. However, another study revealed that in urban areas where health personnel is likely to be higher and transport facilities and distance to health care services are more accessible, the utilization of facility based care is still low because women in Bangladesh might have a strong attachment to get home based care not only just for ANC but also for delivery care which is mostly medically untrained health personal with whom they have closer social links, therefore, convincing women to use facility based care, which is actually free of charge [48-49], is an uphill task [50]. Several studies also pointed out that the low utilization of maternal health care in rural areas [32] is because people believe that pregnancy is just a mere natural process and need no special medical intervention and women and her family also rates the services of TBA more important and useful than the skilled medical personnel concerning communication and relationships [2, 51-52]. Moreover, early initiation of ANC considered as a significant factor associated with the utilization of optimum ANC 4 service [53]; in contrast, delayed initiation of ANC increases the risk of under utilization of ANC services and the delaying could be the effect of cultural and superstitious beliefs about pregnancy disclosure and women might not feel the importance of seeking ANC services until any complications arises [54-55]. Regarding the issue mentioned, maternal education can play an important part in decision making and in the present study maternal education was strongly associated with ANC 4. Educated mothers tend to have better understandings about their own health care, have improved ability to select appropriate and effective facility based health care services, can manipulate their surroundings to have control over their own health care and have increased financial preparations than their counterparts who lacked proper education [2, 51, 56-58]. According to this study, more than 38% of women who had secondary or higher education received ANC 4, whereas, the proportion drops down to 8.9% for the women who did not have any formal education which implied the importance of female education for maternal health care utilization. Moreover, only around 25% of women took decision alone on their own health care which showed lack of empowerment of women in the society. Physical accessibility of receiving health services and an effective health system coupled with increased female education can significantly contribute in the reduction of maternal mortality and that has been portrayed in different region of the world in the marked reduction of MMR [58]. A. S. M. Shahabuddin et al (2015) also pointed out education as the most important factor in the use of skilled maternal health services among married adolescent women in Bangladesh [33].Household wealth status also found to be strongly associated with ANC 4 and the findings showed huge gap in the utilization of services between the women of poorest and richest household wealth index group. This marked as a deep rooted poverty still prevails in Bangladesh though the country has maintained an impressive track record of six percent economic growth over the past decade along with mentionable improvements in human development, however, about 40% of the population still lives below the poverty line and maternal health care utilization also get compromised and aggravated because of that [28]. Another trend analysis by WHO revealed that ANC is heavily influenced by household wealth and women living in households with poorest wealth quintile use ANC services much less frequently than those in the richest group [59]. Another study noted that women from the richest household tend to give birth more in facility based care than their poorest household counterparts [60]. Shahjahan M et al. (2017) also revealed that family income had significant association for receiving both antenatal care and postnatal care services in Bangladesh [29].Moreover, optimum number of ANC visits along with maintenance of timing is very important because inadequate ANC visits make pregnant women susceptible to increased risk of poor pregnancy outcome, maternal morbidity [61-62] and according to several study findings if mothers fail to take advantage of proper ANC the danger of maternal mortality increases by 10 to 17 times [63-64].Furthermore, husbands’ education and occupation also found to be strongly associated with ANC visits and the proportion of the women received optimum ANC 4 increased when husband had higher education and professional/technical job compared to the husband who were not that educated and had jobs other than professional/technical one. In addition, the likelihood of receiving ANC 4 decreased with the increase of the mother’s age and high birth order as well as with big family size and when religion was Islam. Several studies also demonstrated association between mothers age and ANC 4 [22] as younger women were less experienced and tend to visit often to the health facilities to make sure the well being of herself and the growing baby, whereas, the older mother with high birth order try to depend on her previous experience of motherhood [32, 46]. Furthermore, the analysis of ANC 4 utilization between mothers of two opposite ends of socioeconomic strata had revealed concerning results as poorest mothers living in rural areas and typically without formal education lagged a lot behind in contrast to their urban, richest and educated counterparts.

5. Conclusions

- The utilization of ANC 4 has been affected by many factors and the central findings entail that utilization of ANC 4 largely affected by the place of residence of mothers (rural to urban), their household wealth status (richest to poorest) and their educational status (educated-uneducated) along with other factors which affects in varying degrees. The study pointed out the distinctions of ANC 4 utilization in richest, educated and urban mothers to the poorest, illiterate and rural mothers which revealed a shocking and agonizing difference. Therefore, a greater focus and emphasis should be given accordingly to address the important determinants responsible for the low and unequal utilization of maternal health care services in Bangladesh.Acknowledgements, Conflict of Interest & Authors AffiliationsThe authors would like to acknowledge and thank Measure DHS for the BDHS data access. The authors also declare no conflict of interest with anyone. Both the authors contributed equally. Md. Ruhul Kabir is a permanent faculty member of Department of Food Technology & Nutrition Science, Noakhali Science & Technology University and Homayra Islam is working as an Assistant Commissioner and Executive Magistrate, Noakhali Deputy Commissioner Office, Government of People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML