-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2019; 9(1): 11-20

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20190901.03

A Proposal for Global and Local Food Policies Modelling

Ana B. G. F. Santos, Enrique Ortega

Laboratory for Ecological Engineering, Food Engineering School, University of Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil

Correspondence to: Ana B. G. F. Santos, Laboratory for Ecological Engineering, Food Engineering School, University of Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The world is facing a great dilemma because the current food production model is not sustainable from the ecological and social perspectives. Therefore, it is necessary to study the public policies adopted in the last century and to analyse new possibilities, in accordance with the XXI century context. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), an agency of the United Nations (UN), developed several food policy proposals aimed at eliminating hunger and malnutrition. In 1974, FAO launched the Food Security Policy influenced by food commodities traders. Two decades later, a critical examination of the effects of Food Security Policy in peripherical countries revealed the degradation of small farmers ecological economies and undesired lateral effects as unemployment, hunger and rural exodus. The main critic came from the peasant movement La Via Campesina, which is an organization of small farmers, indigenous people and rural workers from all over the world, and also researchers committed to their cause. They presented, as an alternative, the Food Sovereignty Policy, to rescue ecological-traditional practices that value the small farming ecological production and environmental preservation. The research proposal will use energy systems modelling to simulate the effects of global food security policy and the trends expected from food sovereignty policy, both studies will offer quantitative and qualitative indicators.

Keywords: Food policy impacts, Fossil energy dependence, Modelling and simulation of economical-ecological transition

Cite this paper: Ana B. G. F. Santos, Enrique Ortega, A Proposal for Global and Local Food Policies Modelling, Food and Public Health, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 11-20. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20190901.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Ensuring the population food needs is an essential duty of governments. In 1778, Thomas Malthus theorized that population growth would overcome food production capacity, generating hunger and misery (ALENCAR, 2001). The problem was solved due to Europeans emigration to the colonies, the use Peruvian guano and Chilean salitre, and food imports from abroad. After the First World War, with the reappearance of hunger, famine was discussed as one of the major global issues by the League of Nations, established in 1919. This organization disappeared when it shows itself incapable of avoiding Second World War (BRAGA, 2016). After the Second World War, the United Nations Organization was created to solve world´s problems. A special agency, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), was created to develop strategies against hunger (SILVA, 2014).Since 1947, FAO has published an annual report "The State of Food and Agriculture" which discusses agriculture and famine all over the world. It was evident the existence of hunger in some countries and the opportunity for preservation of food raw-materials by industrial processing. Consequently, FAO (1947) main strategy was "modernizing" farm production using chemical fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, irrigation works and, also, food exports to countries with food shortages, quite common in countries devastated by war. In the 70s, FAO's objectives were: food prices stabilization, creation of buffer stocks, and crops industrialization to cope with food lacks (FAO, 1975). The concept of "Food Security" was launched at the World Food Conference in 1974. It was defined as “the availability of adequate world food supplies, at all times, to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices” (FAO, 2006). In 1983, Food Security focused on “access to food commodities" and the need "to ensure that all people have physical and economic access to the basic food that they need" (FAO, 2006). In 1996, in Rome, the FAO World Food Summit´s Plan of Action established food security as “access, use, and availability, since even with increased agricultural production, there was difficulty for families in buying food and also instability in supply and demand that prevented food security from being achieved”. The Rome Declaration states that "food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life". Meanwhile, the existence of environmental problems was recognized as a fundamental factor for satisfying human needs and demands strategies at the regional and international levels, and the coordination between institutions, societies, and economies (FAO, 1996). In 1996, the global movement of peasants, indigenous people, farm workers, and research organizations from all over the world, called “La Via Campesina”, criticized the concept of food security proposed by FAO, since it excluded and harmed small rural producers by means of unemployment, hunger and rural exodus. This movement suggested a new policy called “food sovereignty” to guarantee the right of peasants to maintain and develop their own food according to local resources and traditional culture (LA VIA CAMPESINA, 1996). This organization defined food sovereignty as "the right of every nation to maintain and develop its ability to produce basic food while respecting cultural and productive diversity”. La Via Campesina assumed that food sovereignty was the main requirement for a genuine food security. A few years later, they added “the need to create public policies based on democratic control of resources, ecological sustainability, equity, cooperation and different type of measures to prevent events that cause damage and bankruptcy” (LA VIA CAMPESINA, 2001).In the International Symposium on Agroecology for Food Security and Nutrition, organized by FAO in 2014, FAO recognized that the concept of "performance" in agriculture, requires a new definition and that the key points for that are: (a) recognizing the reality of small family farmers; (b) reduction of fossil fuels dependence to decrease negative impacts on society and environment; (c) actions based on local agroecological knowledge and, finally that(d) a sociopolitical context favorable to agroecology must be achieved to reduce the destruction of environmental resources, for the biodiversity protection and for the payment of environmental services. FAO recognized that "Biodiversity" is an essential component for the resilience of the rural system and it must be maintained without burdening small farmers, as a biological capital that facilitates adaptation to a future without fossil fuels and with strong climatic changes. Important factors for the transition to real sustainable development are the ownership of land and seed autonomy (FAO, 2015). In recent publications (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, 2017, FAO, 2018), it is considered that the achievement of the food security objectives depends on progress in rural areas and strengthening the local economy in an inclusive and sustainable pathway. They recommend taking into account the untapped potential of food systems for agroindustry development and measures to support small-scale farmers. The United Nation’s goals in Agenda 2030 include to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, 2017). These organizations estimate that 815 million people around the world suffer from chronic malnutrition, which indicates that there is still much to be done for quality of life, prosperity, and peace. The food security concept changed in past decades approaching more and more towards human rights policies. Unfortunately, the basic solution considered by these organizations is food production increase using the agribusiness or industrial perspective.However, FAO (2018) recognizes the importance of agroecology as a factor that can achieve the goals proposed in Agenda 2030. The agroecological approach can solve the real causes of hunger and has proven to be a solution to maintain the existing resilient communities in a path that integrates the social, economic and environmental dimensions of sustainability. The agroecological solution arises from family and community farmers, as indigenous peoples, “African descendants’ communities”, riverine fishermen, rural women, and young people. It seems, each day more clearly, that the junction of scientific knowledge with popular wisdom can build the ideal scenario that meets future needs (REGANOLD & WACHTER, 2016; NICHOLLS & ALTIERI, 2018).Food sovereignty emphasizes the study of the internal and external relations generated by capitalism and the impacts it causes on the environment, as well as the autonomous and democratic control of land, water, and ecological management (JAROSZ, 2014).The food sovereignty defended by Via Campesina implies in respect for the native productive capacity and cultural diversity of each nation and rejects the intrusion of international capital and technology. This movement argues that agroecological practices, based on new and ancestral knowledge in harmony with nature, are capable of feeding the world, building equitable alliances between people, organizations and movements of the countryside and the city (LA VIA CAMPESINA, 2017). It is a very important issue that, as Dussel proposes (2003), deserves a critical political attitude in order to change the destiny of many people.

2. Food Security and Food Sovereignty: It is Necessary a Systemic Comparison

- The scientific literature review reveals the world´s food and hunger issue complexity. Therefore, there is a need of analysis, formulation and forecasting of public policies. The comparison of security and food sovereignty politics, in a systemic and dynamic perspective, using energy systems modelling (ODUM & ODUM, 2000) can allow a critical analysis. A holistic point of view is necessary to identify the most important parameters and variables that can be used in the modelling and simulation of these two policies. A systemic perspective allows to investigate the performance of the complex phenomena of food production, trade, consumption, and recycling of nutrients and their impacts on the environment and society, aiming to base technical decisions and public policies.

3. The Emergy Modeling of Food Security and Food Sovereignty

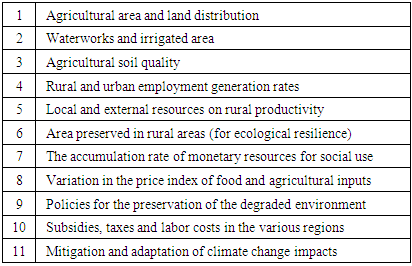

- Howard Odum (1924-2002) believed that systems modelling tools, based on minimodels, would facilitate the understanding of complex systems, using unified concepts that encourage systemic thinking to induce appropriate actions. The emergy methodology, proposed by him, allows discussion of the interaction between human and natural systems. It allows the evaluation of all the contributions of nature and human economy, in terms of previous work, as equivalent aggregated solar exergy or emergy (ORTEGA et al., 2008). It can measure carrying capacity, ecosystem services, negative externalities, yield ratio, investment ratio, emergy exchange ratio, fair price etc. Emergy modelling is based on open-systems thermodynamics, chemical kinetics, and electrical circuits concepts aiming to represent the evolution of ecological and socioeconomic systems in a dynamic form (ONCKEN, 2017; ODUM 1972). Some of these “minimodels” will be used to build-up the simulation models of food security and food sovereignty policies, among them are the following:

A set of mini-models based on the analysis of the global problem of food production, trade and consumption will be prepared to infer the relationship between a pair of countries that obey the FAO food security policy. Food security suggests the purchase of subsidized food produced in a country with a large capacity to produce agrochemical food and a country with an ecological peasant agriculture with limited food production capacity in a process that ends with the destruction of national policies aimed to protect the peasant economy and does not bear the consequences. After that, other two models will allow to discuss the ecological transition and the operation of fully sustainable communities.

A set of mini-models based on the analysis of the global problem of food production, trade and consumption will be prepared to infer the relationship between a pair of countries that obey the FAO food security policy. Food security suggests the purchase of subsidized food produced in a country with a large capacity to produce agrochemical food and a country with an ecological peasant agriculture with limited food production capacity in a process that ends with the destruction of national policies aimed to protect the peasant economy and does not bear the consequences. After that, other two models will allow to discuss the ecological transition and the operation of fully sustainable communities.3.1. Criteria Used for Food Security and Food Sovereignty over Time

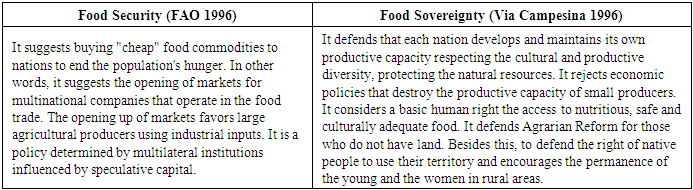

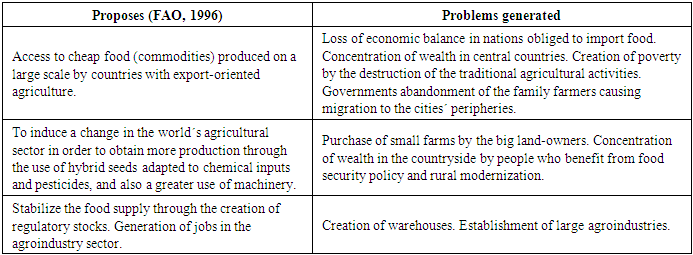

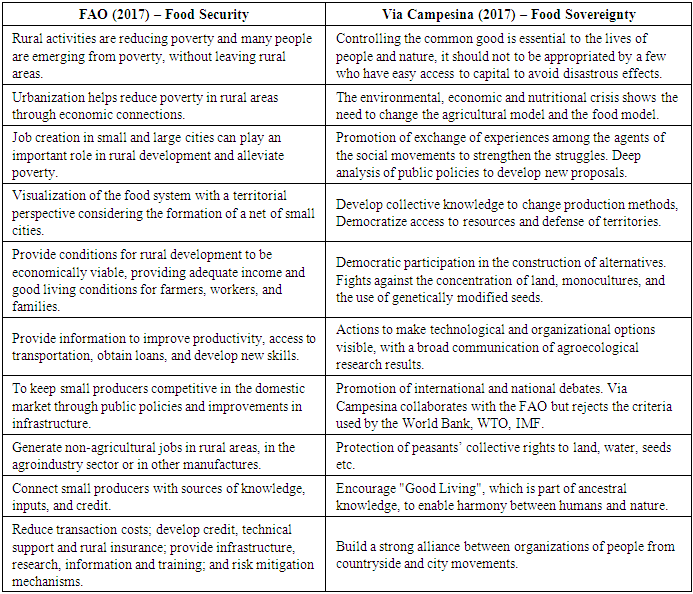

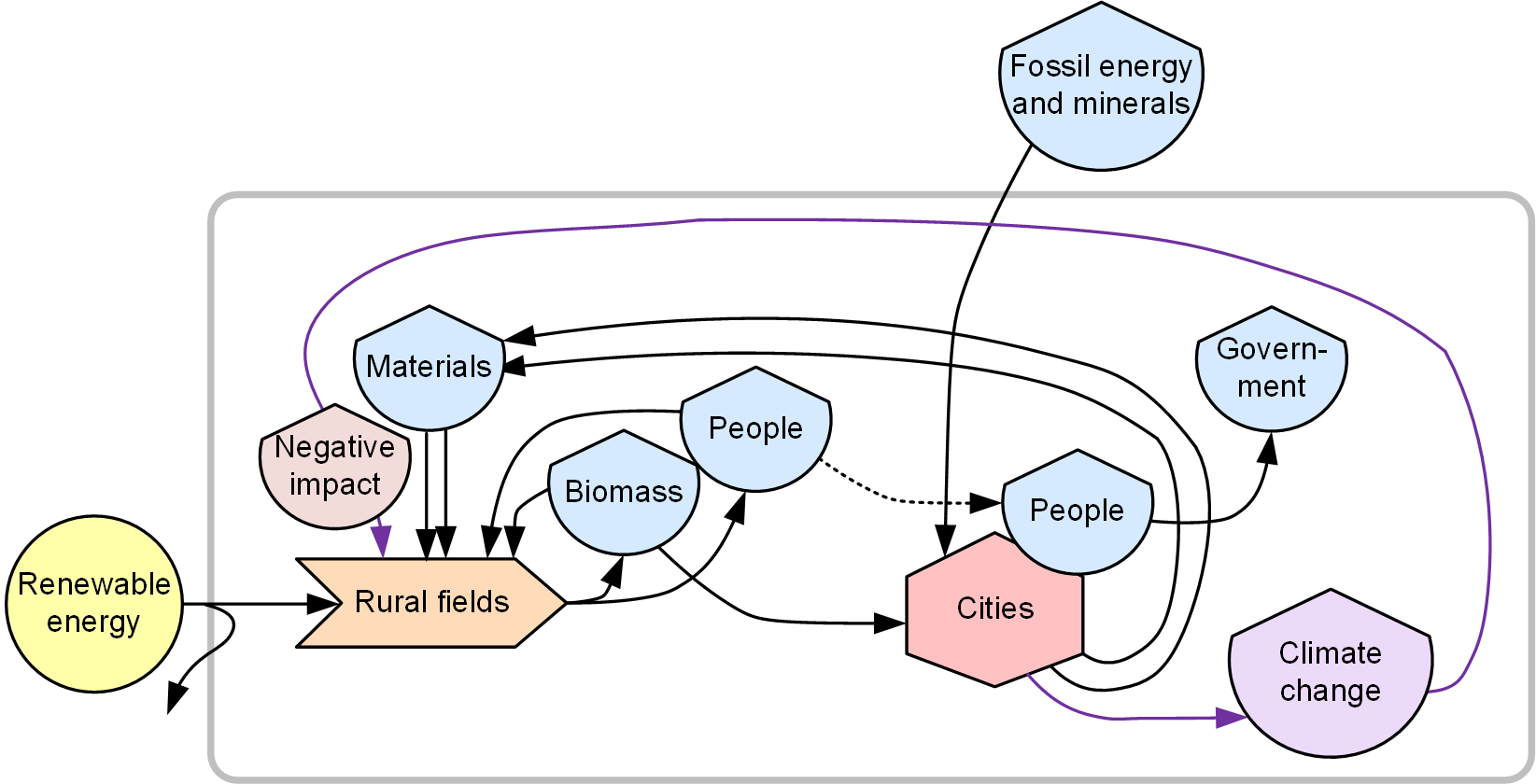

- Tables 1, 2 and 3 present the criteria used for food security and food sovereignty over time.

|

|

|

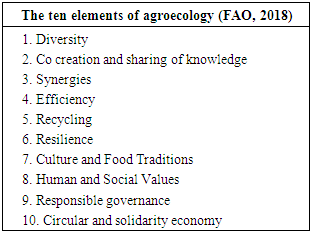

3.2. The Proposal of Agroecology

- According to FAO (2018), three-quarters of the 815 million people that suffer hunger are food producers. Therefore, Food Security Policy is not obtaining its desired results. The farmers´ poverty needs to be placed at the heart of innovation systems. On the other side of food problem, one-third of the world’s population is overweight, and suffers from obesity and chronic diseases due to the consumption of unhealthy food. The current chemical-based agriculture model provides large amounts of food for global markets but does not offer well-being. It uses toxic external inputs, generate deforestation, water scarcity, biodiversity loss, soil depletion, greenhouse gases emissions. A sustainable food production should ensure real food security and good nutrition, social well-being, economic equity, and biodiversity conservation to produce ecosystem services on which agriculture and society depend. Agroecology is able to face-up the future needs, focusing on communal and family farming, maintained until now by indigenous peoples, riverine fishermen, mountain farmers and pastoralists. This productive model provides long-term solutions based on shared knowledge; that combines local, traditional knowledge with multidisciplinary science. (FAO, 2018). Although not a new concept, agroecology is gaining interest among many, as an effective response to climate change and the challenges of food provision. FAO´s recent engagement helps agroecology to bring together knowledge and experience from ecological producers’ organizations, research institutions, public organizations and the private sector. Each partner can contribute to a better world through coordinated action and collaboration (DUSSEL, 2016). Agroecology can contribute decisively to the Objectives of Sustainable Development (ODS) and the achievement of the objectives of the Paris Climate Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (FAO, 2018). Table 4 presents the ten basic and interrelated elements of agroecology:

|

|

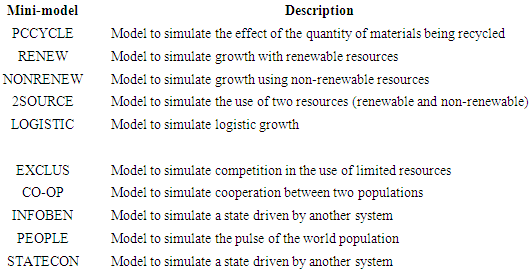

4. The Composition of a Mini-Model to Simulate the Effect of Food Policies

- Five centuries ago, Portugal and Spain developed transcontinental navigation to occupy Africa, South Asia and America, for their own benefit. Three centuries ago, the Industrial Revolution allowed the use of non-renewable resources in agriculture, industry and transport (DUSSEL, 2000). The Renew model (ODUM and ODUM, 2000), represents the natural resources use in an ecological form that prevailed until in the beginning of the 20th century in Latin America despite resources extraction by foreign countries (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Diagram of Mexico's energy flows in 1900 (based on Odum and Odum, 2000) |

| Figure 2. Diagram of energy flows of USA in 1900 (based on Odum and Odum, 2000) |

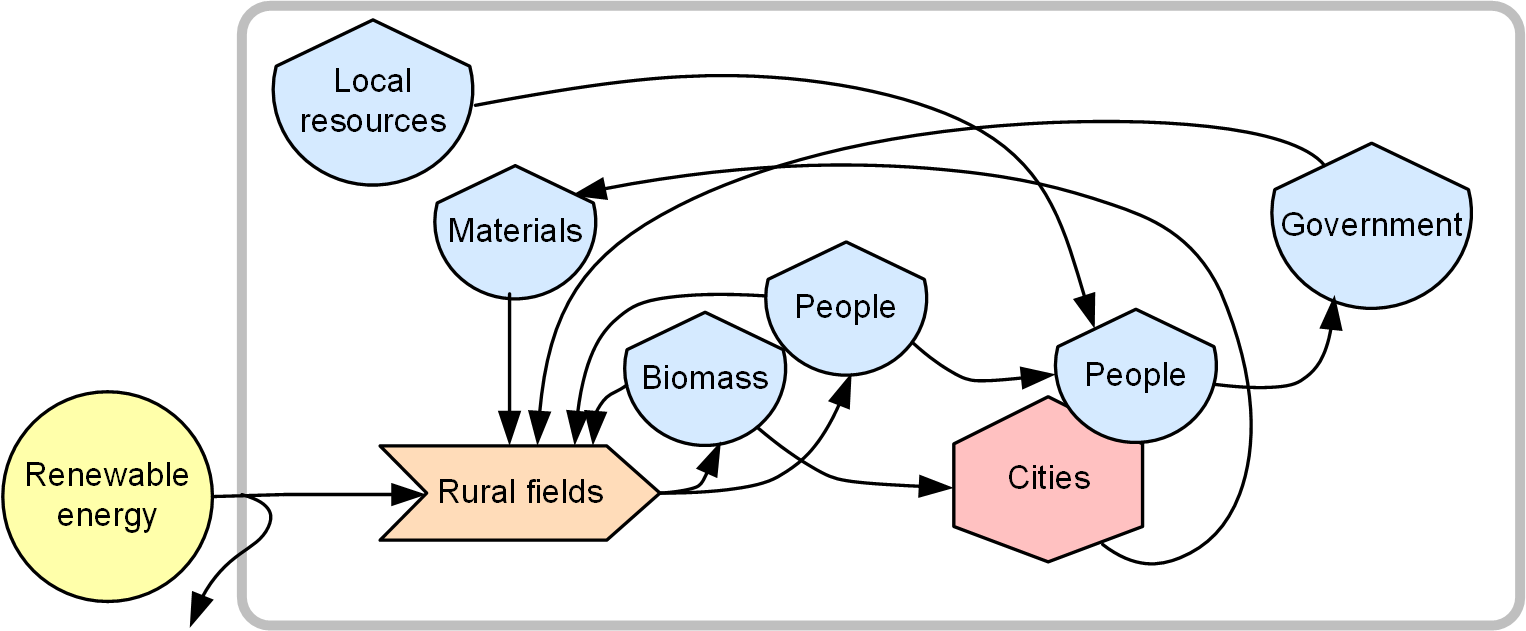

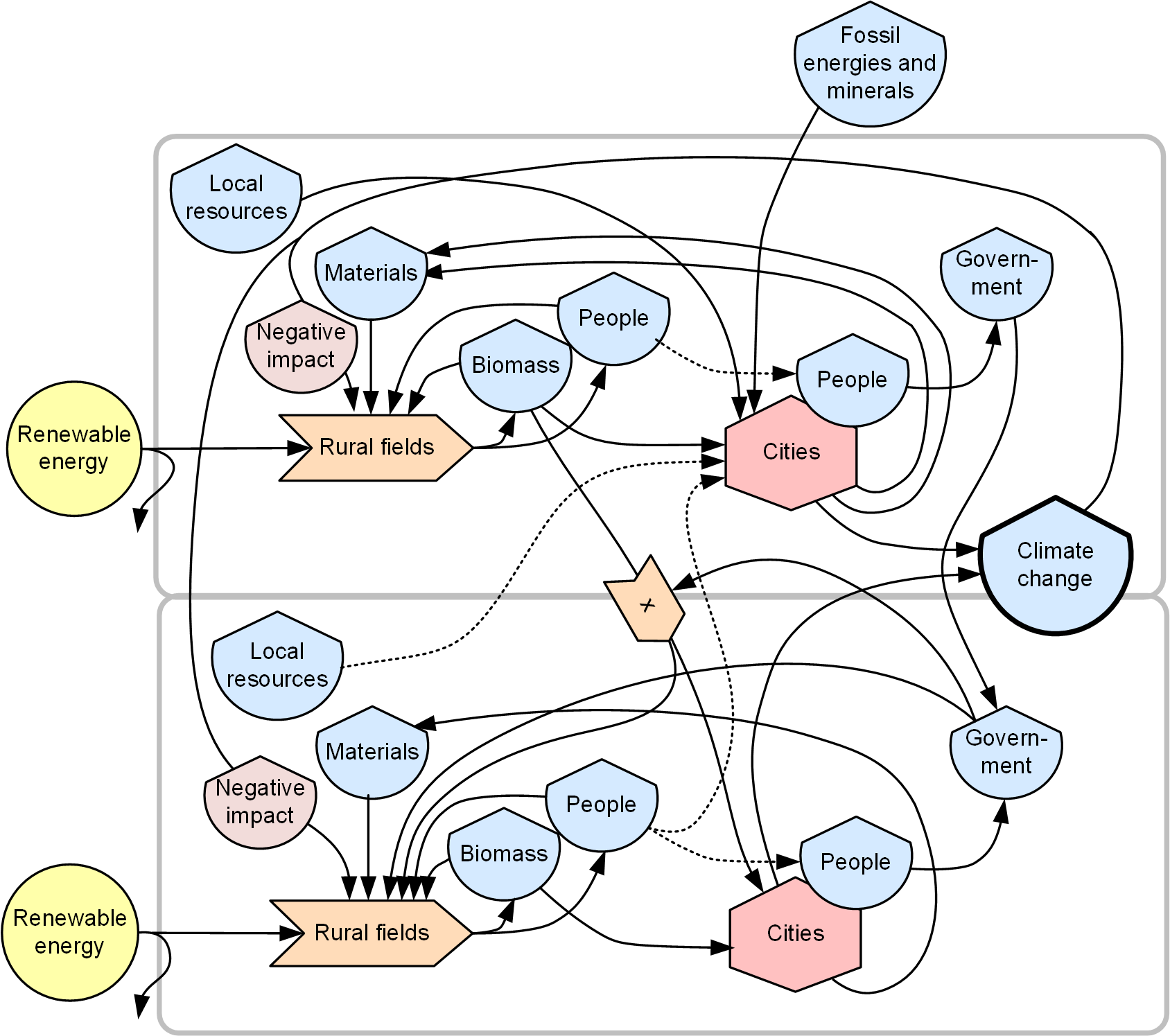

4.1. FOODSEC

- The first proposed model (FOODSEC) represents FAO's food security policy and its effects on the food importing and raw-materials exporting of peripheral nations. This model was build-up after considering two other minimodels: 2SOURCES and STATECON (ODUM and ODUM, 2000). The small-scale, self-sufficient family and community production was replaced by large-scale farms, with monoculture, imported industrial inputs, production oriented to export and great environmental damage (SCHANBACHER, 2010). A subsidized economy based on oil, that has greater force than an economy based on renewable resources. This interaction involves privatization, deregulation, trade incentives, farm specialization and growth and, ownership concentration (GROSFOGUEL, 2007).

| Figure 3. Diagram of food for resources exchange (based on Odum and Odum (2000) |

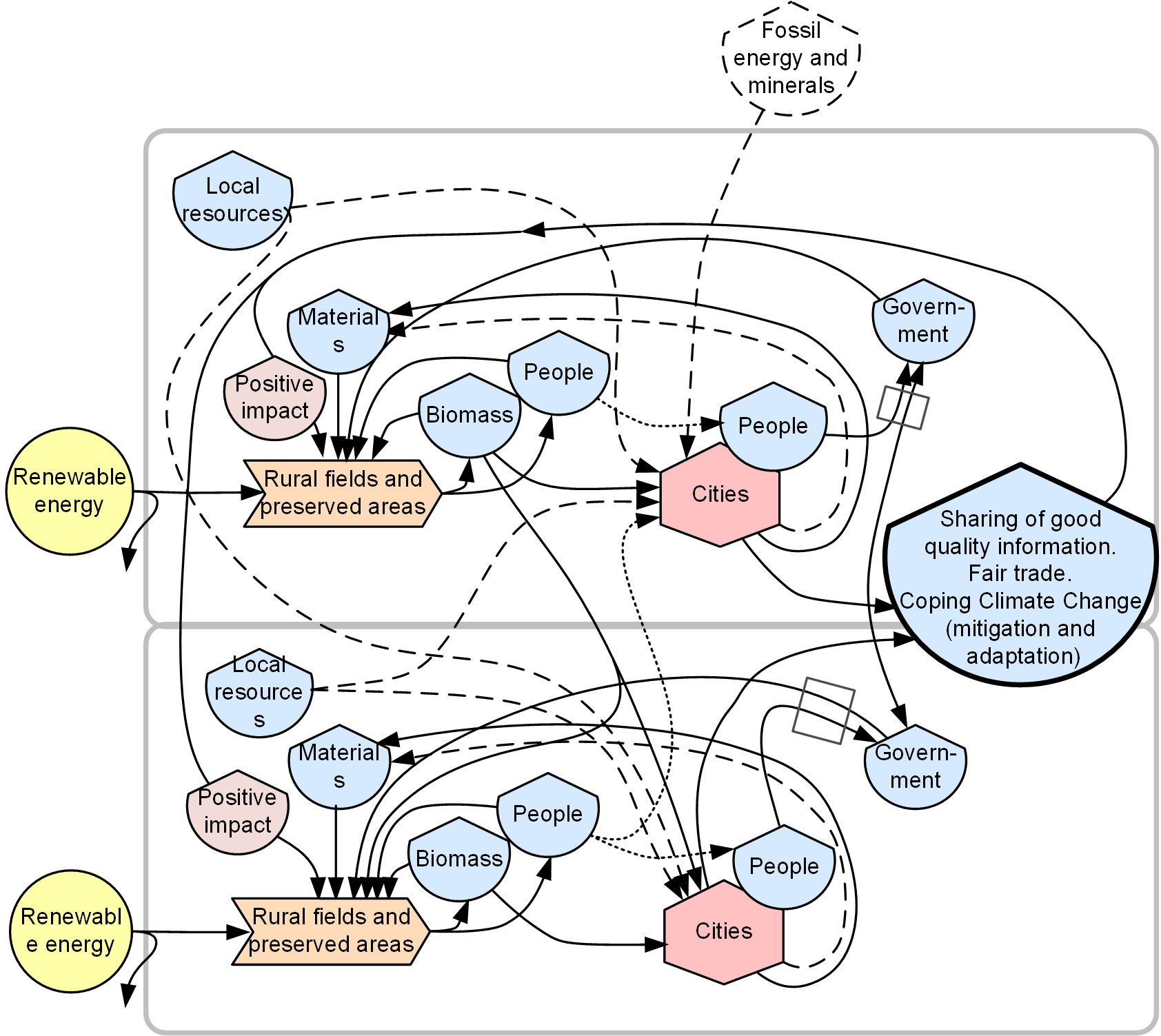

4.2. COOP

- The COOP minimodel (ODUM and ODUM, 2000) represents the transition, with shared use of strategic resources and good quality information. The concept of food sovereignty overcomes the concept of food security since the public policies created from this FAO concept did not achieved real success for several decades. Food sovereignty emphasizes the vision of community and family agriculture, occupying large biodiverse spaces, sharing ecological knowledge, emphasizing local and regional consumption, and innovation based on community cooperation (SCHANBACHER, 2010).Important studies of several scientists, conclude that globalization is not beneficial to the majority of the population and that only through the change of cultural values and public policies that will be possible the social and environmental advances needed for the planet (DUSSEL, 2000; BARTRA, 2011). The following list, shows the parameters that affect food sovereignty according Via Campesina´s ideas and it complement Table 5, both will be merged and considered in the modelling and simulation of the historical process under research and in the prediction of future scenarios.Food sovereignty factors (LA VIA CAMPESINA, 2017):1. Unemployment in rural and urban areas2. Income distribution in rural and urban areas3. Variation in the area of ecological agrarian reform4. Policies to preserve cultural and productive diversity5. Decentralization and degrowing Policies6. Research policies involving the issue of hunger7. Policies for valorization of rural work8. Alliances between rural and urban organizations9. Promotion of agroecological practices10. Job creation in cities and rural areas

| Figure 4. Diagram of countries adopting new priorities (based on Odum and Odum, 2000) |

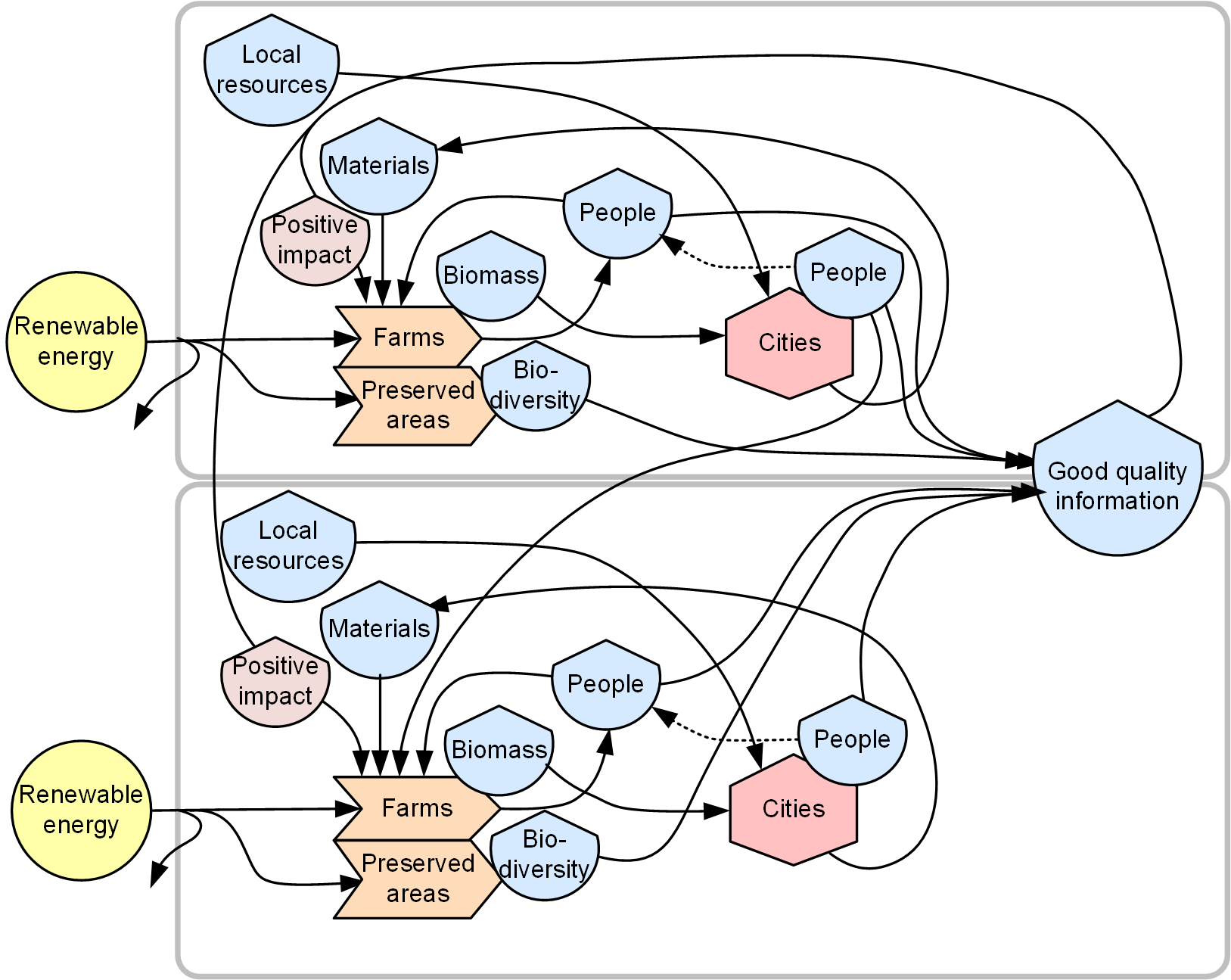

4.3. INFOBEN

- The INFOBEN model (ODUM and ODUM, 2000) implies in the use of shared information and economies based on local renewable resources; in sustainable, independent and biodiverse systems. The model assumes that the development of good quality information will enable a new pattern of coexistence among nations, with renewable power maximization at all levels and fair relations. This model would allow local resources to be used in the production of food, fiber and bioenergy, and recovering of preservation areas, with a positive impact on the environment and society.

| Figure 5. Diagram of emergy flows from countries with high sustainability and biodiversity (based on: Odum and Odum, 2000) |

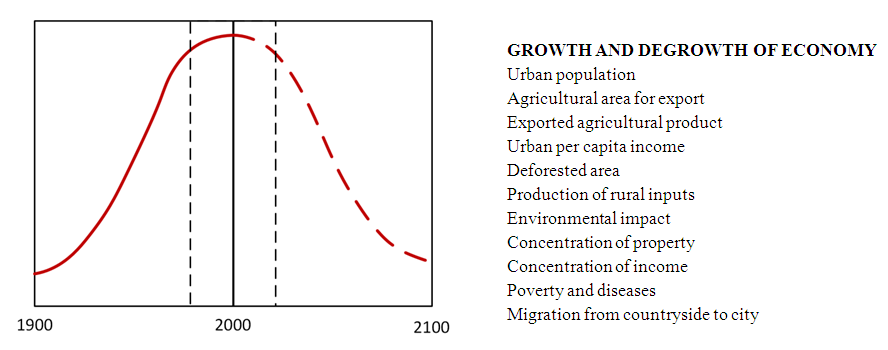

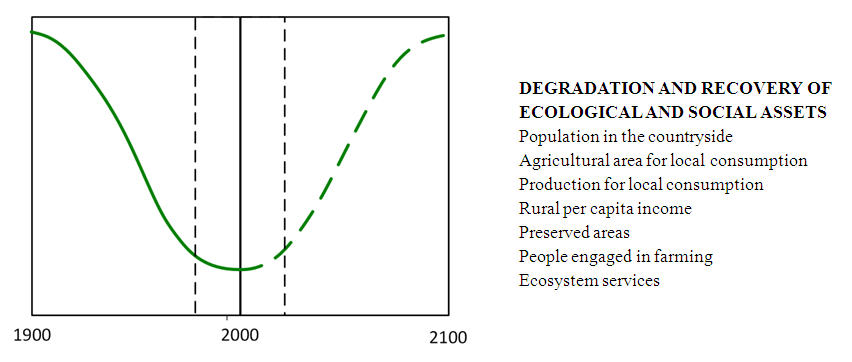

5. Expected Outcomes

- The emergy balance of the two countries system to be studied and the simulation of its performance over the period of adoption of the policy of food security and food sovereignty policies would lead to obtaining curves similar to those in Figures 6a and 6b, below shown.

| Figure 6a. Expected results in two countries relation, with different histories and resources |

| Figure 6b. Expected results in two countries relation, with different histories and resources |

6. Conclusions

- The emergy modelling and simulation is proposed to reveal the effects of global public policies assumed during capitalist expansion and also to forecast future scenarios, considering an economic downturn, and, at the same time, a natural spaces recovery. The software application to be created can play a critical role in discussing effective public policies to address critical issues, such as hunger, because they allow the analysis of ecological-economic complex phenomena with deterministic equations that simulate the interrelations with a holistic perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nível Superior do Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML