-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2019; 9(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20190901.01

Risk Factors Associated with Diarrhea Disease among Children Under-Five Years of Age in Kawangware Slum in Nairobi County, Kenya

Reuben Mutama, Daniel Mokaya, Joseph Wakibia

Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Juja, Kenya

Correspondence to: Reuben Mutama, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Juja, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Purpose: The cause of childhood diarrhea multi-factorial. Interaction of socio-demographic, environmental, cultural and behavioral factors influences the occurrence of childhood diarrhea morbidity. Diarrhea disease is among the top ten causes of under-five mortality and morbidity in Kenya. Thus, it is indispensable to find out factors associated with childhood diarrhea at a community level. The main objective of this study is to find out risk factors associated with diarrhea among children under-five years of age in Kawangware slum in Nairobi County. Methodology: A cross-sectional study was carried out to examine the risk factors for childhood diarrhea among under-five in Kawangware slum in Nairobi County. A total of 198 mothers/caregivers who had lived in Kawangware slum for at least one year and have at least one child above one month but less than under-five and should have lived in the household. Data on diarrhea outcome and its determinants was based on two-week recall and self-reporting of ill health by respondents using systematic sampling technique. The data was analyzed, coded and filtered using SPSS software version 21.0. Findings: Diarrhea cases occurring within the 2 weeks preceding the interviews were reported for one in four children’s, giving an overall prevalence of 37.3%, a prevalence much higher than the prevalence in Nairobi county of 15.6%. The behavioural factors investigated included hand washing, bottle feeding, latrine utilization, length of breastfeeding, disposal of infant faeces, method of water storage and breastfeeding. Among these factors, hand washing, bottle feeding, latrine utilization, disposal of infant, faeces and method of water storage were found to be significantly associated with diarrhea among children under-five years of age since their p-values <0.05. Unique Contribution to Theory, Practice and Policy: The study shows knowledge parity and to some extend traditional and cultural beliefs still plays an immense role towards influencing the behaviour of maternal/caregiver in the event that there is outbreak of childhood diarrhea in the community. There is need to expand the existing child health programmes and put more emphasis on understanding existing traditional and cultural beliefs and set up structures targeting maternal/caregivers on better ways of handling incidence of childhood diarrhea.

Keywords: Childhood diarrhea, Socio-demographic, Under-five, Diarrhea, Cultural beliefs

Cite this paper: Reuben Mutama, Daniel Mokaya, Joseph Wakibia, Risk Factors Associated with Diarrhea Disease among Children Under-Five Years of Age in Kawangware Slum in Nairobi County, Kenya, Food and Public Health, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20190901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Diarrhea has long been established as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world, accounting for 9% of all deaths among children under-five years of age worldwide in 2015 (UNICEF, 2016). This translates into over 1,400 young children dying each day, or about 530,000 children a year, despite the availability of simple and effective treatment. Most deaths from diarrhea occur among children less than two years of age living in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Despite this heavy toll, progress is being made in reducing deaths. From 2000 to 2015, the total annual number of deaths from diarrhoea among children under-five years of age decreased by more than 50 percent from over 1.2 million to half a million (UNICEF, 2016). It is estimated that roughly 780 million people around the world lack access to clean drinking water and an estimated 2.5 billion people (roughly 40% of the world’s population) are without access to safe sanitation facilities. Nearly half of all people using unimproved drinking water sources live in Sub-Saharan Africa; while one fifth live in southern Asia (WHO, 2016).In Kenya, just like other developing countries, diarrhea is a major cause of child mortality and morbidity and comes third after neonatal causes and pneumonia, respectively. Every Kenyan child under the age of five experiences an average of three bouts of diarrhoea every year, according to the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS, 2014). Figures from the KDHS 2014 also show that the prevalence of diarrhea is highest in children aged between 6 and 11 months, followed closely by children between the age of 12 and 23 months.Approximately 71% of households in Kenya obtained water from an improved source, while 27% obtained drinking water from non-improved sources. Approximately 4 in 10 urban dwellers (43%) used an improved facility that is shared by two or more households, as compared with only about 1 in 10 (12%) rural dwellers (KDHS, 2014). Despite diarrhea being a disease that is easy to prevent and treat in Kenya, it continues to be a burden to the Kenyan population where approximately 100 children die every day from diarrhea (UNICEF, 2013).

2. Methods

- Study design and settingA descriptive, cross-sectional design was used to conduct the study among households of Kawangware slum from June to July 2018. The setting of this study was in Kawangware slum, located approximately 15km west of the city centre of Nairobi. The area population was approximately 300,000 in 2009 and it was estimated that 65% of the population were children and youths. Presently Kawangware residents represent all the major Kenyan ethnic, with some areas being specifically dominated by people of one ethno-linguistic group (Kenya Population and Housing Census 2009). These factors makes Kawangware slum an ideal area of study because more than half of the tribes and cultures found in Kenya were represented. Systematic random sampling was used to select the households where responses were filled in the questionnaire. Thus: 10,080 households/198 sample population=50.50. The ratio of 1:51 was used when administering the questionnaire. The researcher sampled every 51st household for data collection and replaced it with the next respondent when the 51st respondent was not available or did not consent the counting started from the 53rd up to the next 51st household till the target was achieved. Data was collected using pretested semi-structured and self-administered questionnaires. Sample sizeThe sample size for this study was determined using the statistical formula of n= Z2P (1-P)/d2 for estimation of single population proportion in prevalence study. In the formula, where n was the required sample size, P was the proportion of diarrhea (prevalence of diarrhea of 15.6%), Z was the standard score corresponding to 95% confidence level (and is thus equal to 1.96) and d was the margin of error (estimated at 5%). With a design effect of 2 for the multistage nature of stratified sampling and a non-response rate of 10%, accordingly, the sample size for the study was 198 households’ mothers/caregivers with under-five children.Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion sampling criteria for this study were: i. Households with a child who had lived in Kawangware slum for at least one year.ii. Primary mother/caretaker was available for interview (mostly the mother)iii. At least one child above one month but less than under-five should have lived in the household. The exclusion sampling criteria for the research were:(i) Institutions (such as offices, hotels, etc.) other than house-holds; and,(ii) Households that did not have child/children under-five years of age. (iii) Households with members who had not have resided in Kawangware slum for more than one year. (iv) The maternal/caregivers who did not consent to participate in this study.(v) Children with persistent diarrhea were also excluded from the study. Ethical approvals Ethical approval for this research was obtained from Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee. Information about the study was explained to the participants, including the objectives, procedures and benefits of the study. There after voluntary informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

3. Data Analysis

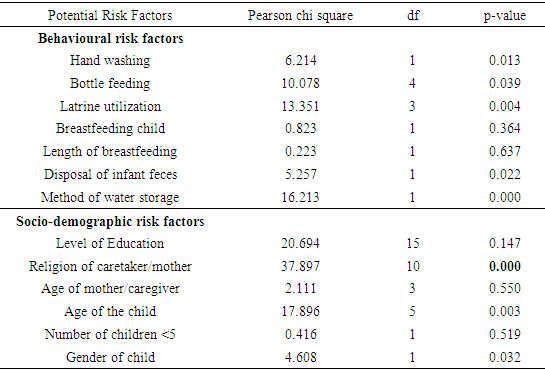

- Data analysis was done using SPSS software version 21.0 after cleaning, coding and entry. The summary results of the descriptive statistics were presented using tables. SPSS software programme was used to identify the determinants of childhood diarrhea. The p-value is the probability of observing a more extreme value in the direction of the alternative hypothesis than the one observed. In order to perform a chi square test and get the p-value, the following information was put into consideration.1. Degrees of freedom i.e. the number of categories minus 1. 2. The alpha level (α). This is chosen by, the researcher. The alpha level set in this study was 0.05 (5%).3. The test statistic in which for this case is the Chi-square test statistic for each categoryIn order to obtain the specific p-values in the Table 4.2 below, R statistical software was used and the command for generating the specified p-values pchisq (test statistic, degrees of freedom, lower. tail=FALSE) the calculated p-value was then compared with the alpha and variables that had less than 0.05 were deemed to be significantly associated with diarrhoea occurrence.

4. Results

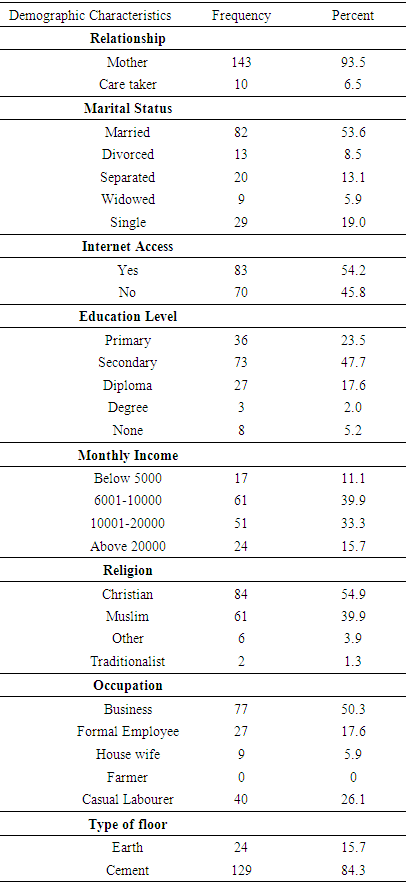

- Demographic Information of the maternal/caregiversMajority of the respondents (93.5%) were mothers and the rest 10 (6.5%) were care givers. In total (53.6%) were married, (19.0%) were single, (13.1%) were separated, (8.5%) were divorced and the minority (5.9%) were widowed. Of those interviewed, 83 (54.2%) indicated that they had internet access, (45.8%) indicated that they did not have internet access. On the education level of the maternal/caregivers, majority (47.7%) indicated they had secondary education, (23.5%) had primary education, (17.6%) had diploma and (2.0%) had degrees. On the income of the households, majority (39.9%) indicated that they earn between 6000 and 10000, 51 (33.3%) indicated that they earn between 10000 and 20000, (15.7%) indicated that they earn above 20000 while the least (11.1%) indicated that they earn below 5000. Regarding the religion, majority 84 (54.9%) indicated that they were Christians, (39.9%) indicated that they were Muslims while (1.3%) reported that they were traditionalists. Majority of the respondent, (50.3%) indicated that they were engaging in business, (17.6%) were in formal employment, (26.1%) were casual labourers and (5.9%) were house wives and with no formal education (Table 4.1).

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

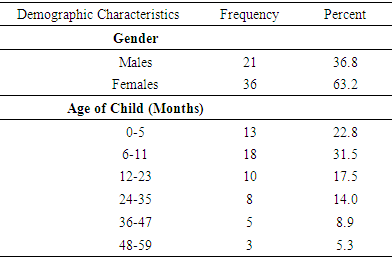

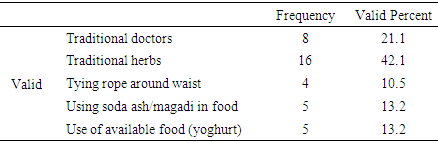

- The results of this study showed that the likelihood of diarrhea in the two weeks period reached its peak at 6-11 months at 31.5% followed by the age groups of 0-5 months with infection rate of 17.5%. The rate of infection falls between 48-59 months to 5.3%. The findings are consistent with studies done globally. In Ethiopia for instance a cross-sectional study to determine prevalence of diarrhea and associated risk factors among children under-five years of age found the peak prevalence of childhood diarrhea to be between 6-11 months (Sinmegn Mihrete et al., 2014). This could be explained by the fact the child starts crawling at this age and the risk of ingesting contaminated materials such as soil hence exposing themselves to predisposing factors that causes diarrhea. However there is a worrying trend of relatively high rate of diarrhea infections of (17.5%) among infants of age groups ranging between 0-5 months compared to other studies done globally. The high prevalence of diarrhea in the area of study among this range of age group could be due to early introduction of supplementation foods and liquid’s hence exposing the child to predisposing factors of childhood diarrhea. These results are also similar to study done in Bankura, West Bengal where high cases of (36.1%) were reported among children who were not exclusive breastfed. diarrhea infections.The gender of the child was a statistically significant predictor of childhood diarrhea infection in the area of study, with boys more than two times more likely to be affected by diarrheal disease than girls in the last two weeks preceded to study. Among the participants in this study, females were more affected with diarrhea (63.2%) than males (36.8%). Similar pattern was reported in Mbour Senegal on prevalence of diarrhea and risk factors among children under-five years which also found that the rate of diarrhea infections was slightly higher among girls compared to boys (Sokhna Thiamon 2017). This might point to a possible cultural influence in this area of study which gives more preference for male child over female by which the nutrition of female children is neglected, restricting their access to health. A study done by (Thiam et al., 2017) in Senegal supports this finding, in this study; it was found that cultural practices overt preferences for boys over girls that might affect how mothers/caregivers take care of children.On the type of traditional remedy used, majority of the maternal/caregiver, (42.1%) acknowledged that they use traditional medicinal herbs to treat diarrhea, (21.1%) used traditional doctors, (10.5%) use tying a rope around the waist (13.2%) use soda ash in food and 13.2% used yoghurt to treat childhood diarrhea. From this study it was also noted that high rate of diarrhea cases were reported among maternal/caregivers who believed in traditional means as a remedy to childhood diarrhea in the area of study. Similar findings were reported by Africa medical research foundation (AMREF 2015) which conducted several in-depth interviews with health providers, community leaders and also held focus group discussions and household interviews for mothers in Narok South found that the community was deeply entrenched in “Myths, superstitions and beliefs in using herbs to treat diarrhea in children under-five of age. The study concluded that high prevalence of diarrhoea among children under-five years of age in the Maasai community was attributed to over reliance on traditional treatment methods of childhood diarrhea.Simple hygiene behaviours, especially hand-washing with soap, have been suggested to reduce the occurrence of water-washed infections. The findings from this study showed that the risk of developing diarrhea was higher among children whose mothers/caregivers with poor hand washing practice. It was also noted that the practice of hand washing after touching faeces was not regular among the mothers/caregivers in Kawangware. Some mothers admitted to washing hands only when there is visible contamination with faecal matter. Some mothers just rub it off or just wipe it off. The outcome of this study about the association between inadequate hand-washing with ‘water and soap’ and incidence of diarrhea disease among children <5 years is in line with various studies. A study done in Ghana, reported that, childhood diarrhea was most prevalent among children whose mothers did not wash their hands with water and soap after defecation (Leslie et al., 2014).Poor handling of drinking water was significantly associated with increased risk of childhood diarrhea. Jinadu et al, (1991) in a study carried out in Nigeria found that poor handling of drinking water was significantly associated with high incidence of diarrhea among children <5 years of age. Knight et al, (1992) also stated that regardless of where or how the water is collected, storage in vessels with wide openings such as pots or buckets easily allow contamination with faeces through introduction of cups, dippers, or hands.

6. Conclusions

- The prevalence of diarrhea among children under-five of age in the area of study was quite high. The highest occurrence of childhood diarrhea was significantly concentrated among children aged 6–11 months; however there was also an increasing alarming rate of infection among children between 0-5 months. As captured during the interview most mothers admitted to early introduction of liquid and solid foods to their young children even before reaching the age of 6 months. The study also concluded that gender of the child was significantly associated with diarrhea infection among children under-five years of age in the area of study. In this study girls appeared more vulnerable to childhood diarrhea infection than the male child. Traditional treatments such as herbal extracts have been the most used in treatment of childhood diarrhea in the study. This may be attributed to the positive values that the community have for them. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out scientific investigation on these different traditional treatments that have been practiced for long time and determine their effectiveness in treating childhood diarrhea. They may add of important values for the modern medical sciences in terms of successful management of childhood diarrhea. This study was also able to show that some households still believes in traditional methods of diarrhea treatment and management, this could pose as significant risk factors for diarrheal disease in children <5 years of age in Kawangware slum. This findings suggest that health promotion programs should place further emphasis on increasing knowledge of how water treatment, hand washing with soap, proper disposal of child feces, and food preparation relates to childhood diarrhea prevention.Future studies should also evaluate behavioral risk factors for diarrhea in this study population, and conduct further formative research to identify cultural and traditional beliefs among maternal/caregivers of children <5 years of age on diarrhea prevention. This information can be used to develop tailored communication messages promoting water treatment, improved sanitation, and hand washing with soap for this susceptible population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- My acknowledgement goes to Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, School of Public Health, Mothers/caregivers, data collectors and supervisors. I would also like to thank Mr. Samuel Mutua for his statistical guidance. May God bless them abundantly!

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML