-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2018; 8(3): 72-78

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20180803.03

Nutritive Value of Bark Extracts from the “White Variety” of Byttneria Catalpifolia, a Wild Edible Plant, Consumed as Stem Vegetable in Western of Côte d’Ivoire

Gonou Aline Tokpa1, Chépo Ghislaine Dan1, Tia Jean Gonnety1, Meuwiah Betty Faulet1, Kouadio Ignace Kouassi2, Adama Bakayoko2, Kouakou Brou3

1Laboratory of Biocatalysis and Bioprocesses, Training and Research Unit in Food Sciences and Technology, Nangui Abrogoua University, Côte d’Ivoire

2Ecology and Biodiversity Research Unit, Training and Research Unit in the Natural Sciences, Nangui Abrogoua University, Côte d’Ivoire

3Laboratory of Nutrition and Food Security, Training and Research Unit in Food sciences and Technology, Nangui Abrogoua University, Côte d’Ivoire

Correspondence to: Chépo Ghislaine Dan, Laboratory of Biocatalysis and Bioprocesses, Training and Research Unit in Food Sciences and Technology, Nangui Abrogoua University, Côte d’Ivoire.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

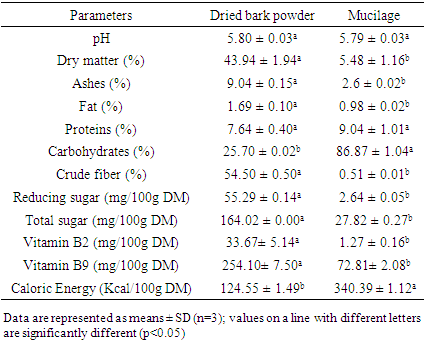

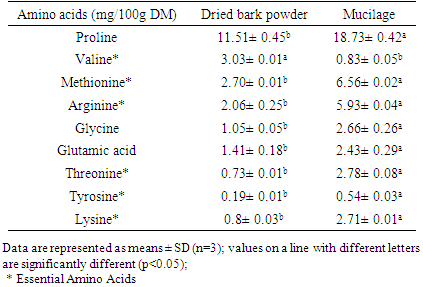

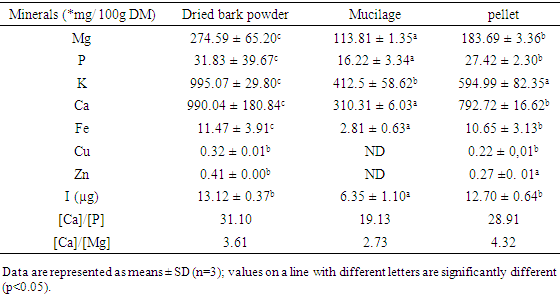

Analysis of bark extracts from “white variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia were assessed in order to provide consumers with information on the nutritive potential of this wild edible plant. Ash, carbohydrates, protein, fiber, fat and moisture were measured using AOAC methods in bark and mucilage. The minerals were analyzed by a variable pressure Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), the amino acid by HPLC and iodine was determined by titrimetry. The bark powder of Byttneria catalpifolia presented the highest percentage of ashes (9.04 ± 0.15% DM), crude fiber (54.50 ± 0.50% DM), total sugar (164.02 ± 0.00 mg/100g DM) and vitamin B9 (254.10 ± 7.50 mg/100g DM). Valine, methionine, arginine, threonine, tyrosine and lysine are more concentrated in mucilage than others extracts. The predominant minerals were Ca (990.04 mg / 100 g DM) and K (995.07mg / 100 g DM) in the bark. But, iodine rates were in the bark, the pellet and mucilage (13.12; 12.70 and 6.35 μg/100g DM) respectively. Thus, the consumption of the bark powder would be more advantageous because it could contribute more to the nutritional requirements of consumers than the mucilage.

Keywords: Byttneria catalpifolia, White variety, Bark, Mucilage, Nutritive value, Edible plant

Cite this paper: Gonou Aline Tokpa, Chépo Ghislaine Dan, Tia Jean Gonnety, Meuwiah Betty Faulet, Kouadio Ignace Kouassi, Adama Bakayoko, Kouakou Brou, Nutritive Value of Bark Extracts from the “White Variety” of Byttneria Catalpifolia, a Wild Edible Plant, Consumed as Stem Vegetable in Western of Côte d’Ivoire, Food and Public Health, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2018, pp. 72-78. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20180803.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Wild plants play many roles in life of many populations. In Africa, thousands of wild plants are used daily by farming communities [1]. They contribute substantially to food by ensuring survival and providing nutrients in diet. They provide food like of fruits, leaves, roots, seeds and other plant parts, either raw or cooked [2]. Unfortunately, nutritionists pay little attention to these plants. Despite this scorn, more and more food products from wild plants are found on markets and even in daily diet of families, reflecting the interest that people relate to these edible plants.Byttneria catalpifolia is one of the most widely consumed wild plant in Côte d’Ivoire especially those in western part. It is a shrub undergrowth forest whose fruit is thorny (Fig. 1a) and contains numerous small black seeds (Fig. 1b) [3]. It belongs to Sterculiaceae family that grows naturally in tropical forests [4]. In the mountainous Western part of Côte d’Ivoire, there are two varieties (white and red) of this vegetable. The so-called "white variety" is characterized by white colour of bark when epidermis is scraped, while the "red variety" is characterized by a purple colour of bark. Stem bark and seeds of Byttneria catalpifolia are used to prepare a sauce which is particularly affectionate by local populations [3]. They extract mucilage from stem bark and add to pre-cooked soups. The traditional method to obtain mucilage consists in removing epidermis from stem barkcrumbling it and kneading it in water with the hand to extract the mucilage. Today, there are new perceptions among consumers, especially those living in cities. For these people, the traditional way of extracting the mucilage with the hand is not hygienic so that they use the powder of the dried bark to prepare the sauce. Even if, Byttneria catalpifolia has been consumed for generations, scientific data of this plant are limited to its nomenclature and its botanical description. To our knowledge, no studies about biochemical and nutritional characteristics have been reported to date. The objective of this study was to assess nutritive potential of extracts from the “white variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia in order to provide consumers with information data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

- For this study, the stem bark (Figure 1b) and the mucilage (Figure 1d) extracted from fresh bark of the “white variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia, were used. The stem samples were harvested from Man (Latitude 7°24’45” North and Longitude 7°33’13” West, Côte d’Ivoire), transported fresh to the laboratory and then identified by the National Floristic Center (University Felix Houphouët-Boigny, Abidjan-Côte d’Ivoire). After removing the epidermis using a kitchen knife, the barks were removed from stems and chopped. The bark sample was divided into two parts. One part consisting of 20 g of fresh stem bark was ground in 200 mL demineralized water using a crusher Moulinex. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was crushed again in 200 mL demineralized water and centrifuged in the same condition as described previously. The two viscous supernatants were mixed and kept in freezer for physicochemical analysis. The other part was dried in an oven at 65°C for 72 h. The dried samples were ground and the resulting sifted (θ 2 mm) powder was stored in sealed plastic boxes for physicochemical analysis.

| Figure 1. Photography of fruit (a), seeds (b), bark (c) and mucilage (d) of the « white variety » of Byttneria catalpifolia |

2.2. Proximate Analysis

- Five grams of the fresh sample of Byttneria catalpifolia was placed in an oven at 105°C until constant weight was attained. The percentage of dry matter was calculated as 100% moisture. The recommended methods of the AOAC [5] were used for the determination of ash, lipid, crude fiber and crude protein and carbohydrates. Reducing sugar and total soluble sugar of the sample was estimated respectively according to the method of Bernfeld [6] and Dubois et al [7]. Calorific values were calculated using the following formulas [8]: Calorific value = (% proteins × 2.44) + (% carbohydrates × 3.57) + (% lipids × 8.37).

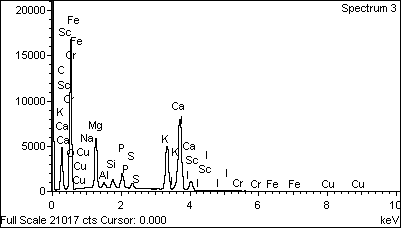

2.3. Minerals Analysis

- The mineral elements were analyzed after wet-ashing using Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with variable pressure (SEM FEG Zeiss Supra 40 VP). This SEM is equipped with an X-ray detector (Oxford Instruments) connected to an energy diffusion spectrometry (EDS) microanalyzer platform (Inca Cool Dry, without liquid nitrogen). About 10 mg of the sample ash residue were applied evenly to a primed platform with double-sided adhesive carbon for analysis. To measure the content of chemical elements, the device performs a measurement of the transition energy of the electrons from electronic clouds of the K, L and M series of atoms of the sample.

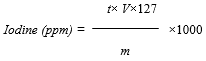

2.4. Determination of Iodine

- Iodine was measured by titrimetry as described by Mannar and Dunn [9] with slight modification. During this reactional process, iodide ion (I-) contained in the mucilage and pellet extracted from the fresh bark and dried bark powder of Byttneria catalpifolia reacted to the presence of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and potassium iodate (KIO3). Iodine released was analyzed using sodium thiosulfate in the presence of starch used as a colored indicator. The volume of sodium thiosulfate used is proportional to the amount of di-iodine contained in the plant. For sampling preparation, 50 mL of distilled water was used for dissolving 1 g of ash in a 50 mL beaker. Then 1mL of sulfuric acid (2N) and 5mL of potassium iodate (10%) were added after stiring. The final solution becomes yellow which is the characteristic color of di-iodine the liberated. The sample was incubed at 25°C in darkness for 10 minutes. One (1) mL of starch solution was added and titrated the solution with sodium thiosulfate (0.005 N) from the burette.Iodine content is given by this following Equation:

t : Normality of sodium thiosulfate (eq·g·L−1).V : Volume of sodium thiosulfate (L)127 : Atomic mass of iodinem : Ash mass of the sample

t : Normality of sodium thiosulfate (eq·g·L−1).V : Volume of sodium thiosulfate (L)127 : Atomic mass of iodinem : Ash mass of the sample2.5. Amino Acids Determination

- Amino acids were assayed by reverse phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (PTC column RP-18, 220 mm in length, 2.1 mm internal diameter) equipped with a pre-column (SHIMADZU SPD 20A). The sample was vacuum hydrolyzed at 150°C for 60 min in a Waters Pico-Tag work station (Waters’ associates, Milford, MA, USA) in grade 6 N HCl at 1% phenol. It was then taken up in ultrapure water and derivatized automatically by means of an auto-derivator-analyzer- 420 (SHIMADZU SPD 20A). The amino acid derivatives in the form of phenyl isothiocyanates (PITC-amino acids) were separated by chromatography system consisted of mobile phase A (45 M sodium acetate, pH 5.9) and mobile phase B (30% 105 mM sodium acetate pH 4.6; 70% acetonitrile) with a linear gradient of 7-36% at 1.5 mL/min. The detection was done at a wavelength of 254 nm and the total duration of the analysis was 31 min. The acquisition and exploitation of the results were carried out using the Model 600 Data Analysis System (SHIMADZU SPD 20A) Software.

2.6. Determination of B vitamins

- A 5 g of liquid/powder sample was extracted with 20 mL of methanol (80%). The stock of standard (Sigma Aldrich analitycal grade reagent) was prepared by dissolving 0.01 g of each standard in methanol (80%). A HPLC system (SHIMADZU SPD 20A) equipped with UV detector (PAD) and C18 ODS column (250 x 4.6, Cluzeau France) was used in isocratic mode for analysis. Mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (55 mL), tetrahydrofurane (37 mL) and water (8 mL) at 1.5 mL/min flow rate and 10 µL of each sample/standard were injected and monitored at 325 nm wavelength.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- All the analyses were performed in triplicate and data were analyzed using STATISTICA 7.1 (StatSoft). Differences between means were evaluated by Duncan’s Test. Statistical significant difference was stated at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Proximate Composition

- The proximate composition of the dried bark powder and the mucilage extracted from fresh bark of “white variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia is shown in Table 1. Overall, pH is acid (5.8). Were observed in the dried bark powder a high quantity of ashes (9.04 ± 0.15% DM), crude fiber (54.50 ± 0.50% DM), total sugar (164.02 ± 0.00 mg/100g DM), Vitamin B2 (33.67± 5.14 mg/100g DM) and Vitamin B9 (254.10 ± 7.50 mg/100g DM) but the mucilage had the highest percentage of carbohydrates (86.87 ± 1.04% DM). Caloric Energy of the bark powder was lower (124.50 ± 1.49 Kcal/100g DM) than that recorded for the mucilage (340.39 ± 1.12 Kcal/100g DM).

3.2. Amino Acid Contents

- The results of amino acid composition indicated that samples of dried bark powder and mucilage contained six essentials amino acids (Table 2). The mucilage enclosed proline (18.73 mg/100g DM), methionine (6.56 mg/100g DM), arginine (5.93 mg/100g DM) and little amount of valine (3.03 mg/100g DM) and lysine (2.71 mg/100g DM).

|

3.3. Mineral Composition

- Mineral contents and mineral ratios of samples are respectively shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. Mineral levels of the bark powder and pellet appeared significantly higher (P≤0.05) than those of the mucilage. Ca (990.04 mg/100g DM) and K (995.07 mg/100g DM) were most important while Cu (0.32 mg/100g DM), and Fe (2.81-11.97 mg/100g DM) were low. Determination of iodine also gived in bark, pellet and mucilage (13.12 μg; 12.70 μg and 6.35 μg/100g DM) respectively. It noted that the ratio [Ca]/[P] for the dried bark powder (31.10), the pellet (28.91) and the mucilage (19.13) were greater than 1. The [Ca]/[Mg] ratios of the samples also exceed 2.

| Figure 2. The chromatographic profile of the bark powder sample |

|

4. Discussion

- Byttneria catalpifolia extracts have a low pH value (5.79 - 5.80), these result suggest that this plant (mucilage and bark) are acidic. According to Bouba et al [10], this acidification allows a good conservation. Thus, Byttneria catalpifolia extracts will not be favourable to the development of the pathogenic micro-organisms so the powder coud be preserved for a long time.Ash values higher than that found by Sahore et al [11] in seeds of Irviginia gabonensis (5.91%) indicated that Byttneria catalpifolia species may be considered as good sources of minerals when compared to values (2-10%) obtained for cereals [12]. As concern to the crude fiber content, its level in the bark largely higher than those of the mucilage and some of leafy vegetables such as Ceiba patendra (31.94%) [13] would be a trump for dietary use of dried bark powder. The major drawbacks to theuse of vegetables in human nutrition is their high fiber content which in variability causes intestinal irritation and lower nutrient bioavailability, hence large quantities of plant vegetables have to be consumed to provide adequate levels of nutrients [14]. On the other hand, intake of dietary fibers can lower the serum cholesterol level, risk of coronary heart disease, hypertension, constipation, diabetes, colon and breast cancer [15]. Thus, dried bark powder could be valuable sources of dietary fibre in human nutrition.The amino acid contents of the mucilage were found generally higher than those of the bark powder. This suggests that bark proteins would be highly soluble in water and could be easily adsorbed by mucilage. Indeed, Nacoulma et al. [16] reported that mucilage is capable of absorbing organic matter dissolved in water. Moreover, physical treatments undergone by the bark (drying, grinding, sieving) to obtain the powder would have led to loss of some of amino acids. Note that collapse of cell structure can destroy cellular compartments resulting in loss of essential nutritional components of plant product [17]. Other studies have also shown that quality of a dried product is often lower than that of original food with an impact on nutritional value [18]. It should be noted that either in the mucilage or in the powder of the bark, protein proportions were very low and not sufficient at all to meet the protein requirements or amino acids balance. On the other hand, extracts of the white variety of Byttneria catalpifolia contained six essential amino acids. The human organism is not able to synthesize directly the essential amino acids necessary for its maintenance and repair, the consumption of mucilage and powder of Byttneria catalpifolia in the sauce could help to overcome this deficit. According to CTA [19] leaves of Moringa oleifera had more proline (1230 mg/100g DM) and remarkable level of valine (1400 mg/100g DM) and methionine (370 mg/100g DM) than our data. Thus, the relatively low protein and amino acid levels in the bark of this plant require supplementation in animal protein or legume protein to meet protein needs of consumers in order to fight against protein-energy malnutrition [20]. In this regard, it is worth remembering that people already consume the sauce made of the mucilage with lots of meat and fish. Thus, this empirical feeding behaviour could help to make up the protein deficit.Regarding group B vitamin contents of the bark and the mucilage, it was observed that vitamins B2 and B9 were not probably well extracted when extracting the mucilage. Indeed, there were relatively more vitamin B9 (254.10 mg/100g DM) and little rate of vitamin B2 (33.67 mg/100g DM) in the bark powder than in the mucilage (72.81 and 1.27 mg/100g DM, respectively). Yarrow (Achillea millefolium L., 257 μg/100g DM) [21] and many edible portion of leaves of raw African leafy vegetables as pigweed (Amaranthus cruentus L., 75 µg/100 g), spider flower (Cleome gynandra L., 121 µg/100 g), pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima Duchesne, 105 µg/100 g) have been reported to contain low amount of vitamins B9 [22]. In contrast, leaves of Moringa oleifera and Spirulina platensis displayed rates of vitamin B2 (8800 mg; 3500 mg/100g DM), respectively [23]. Given the difference between vitamin B contents of the bark and the mucilage, the use of the bark powder would be more advantageous compared to the mucilage, due to its B vitamins profile.As concern lipid, it should be noted that the relatively low value in our samples corroborate the findings of many authors which showed that vegetables are poor sources of fat [24]. The estimated calorific values agreed with general observation that vegetables have low energy values due to their low crude fat and relatively high level of moisture [25]. However, it’s important to note that diet providing 1-2% of its caloric energy as fat is said to be sufficient to human beings, as excess of fat consumption yields to cardiovascular disorders such as atherosclerosis, cancer and aging [26]. Therefore, the consumption of the bark of this white variety of Byttneria catalpifolia in large amount may be recommended to individuals suffering from obesity rather than mucilage that displayed energy value of 340.39 Kcal / 100g DM. The energy value (124.55 Kcal / 100g DM) for the stem bark powder of this vegetable was relatively low. Oulai et al. [27] noted that Andasonia digitata and Amaranthus hybridus energy values were respectively (305.19 Kcal / 100g) and (267.03 Kcal / 100g).Mineral content is an essential component of the nutritive value of vegetables. Our results showed that the bark of “White variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia can be considered as a good source of mineral. Data showed that K levels were relatively lower in the bark of this plant (995.07 mg/100g DM) than the values observed for leafy vegetable Amaranthus hybridus (1258.43 mg/100g DM) [28], but higher than that found by Bouba et al. [29] in bark of Hua gabonii (371 mg/100g DM) and bark of Scorodophleus zenkeri (368 mg/100g DM) used as stem vegetables in Cameroon. The bark of “white variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia was very rich in Ca (990.04 mg/100g DM) compared to stinging nettle (Urtica dioica 68.77 mg/100g DM) leaves [30], seeds of Beilschmiedia manii (104 mg/100g DM) and Amaranthus hybridus (360.04 mg/100g DM) [11]. It is important to note that Ca and P are associated with the growth and maintenance of bones, teeth, and muscles, while K can play a role in lowering blood pressure [31]. In addition, it is also well-known that the absorption of Ca and Pare interdependent, depending on their ratio. Thus, the [Ca]/[P] ratios (26.66 and 3.37 for the bark and the mucilage respectively) higher than 1, might be advantageous for consumption of the studied bark or mucilage because, diet is considered good if the ratio [Ca]/[P] is > 1 and as poor if < 0.5 [32]. In the extracts of this food plant, the ratio [Ca]/[Mg] (2.73 - 4.32) is higher than 2. Magnesium is required for the use of Ca and Ca promotes the absorption of magnesium. The optimal ratio between these two minerals in the diet is from 2 to 1 in favour of Ca [27].It contained also more iodine (13.12 μg/100g DM) in our bark, than in peanut (12.25 μg/100g DM), eggplant leaves (7.6 μg/100g DM) and melon leaves (6.13 μg/100g DM) studied by Taga et al. [33] in Cameroon. However, it should be important to noted that in western part of the Ivory Coast, where Byttneria catalpifolia is much consumed, there is an endemic disease named goiter. We also noticed a highest content of minerals in the pellet compared to mucilage. Iodine is an essential substrate for the body and for the synthesis of thyroid hormone [34, 35]. Lack of iodine in our diet causes various abnormalities qualified as disorders due to iodine deficiency (endemic goiter, hypothyroidism, cretinism, lack of reproductive function, anemia, spontaneous abortions and infant mortality) [36-38]. Therefore, the best way to exploit this plant to benefit from the Iodine it contains is the use of the bark powder.

5. Conclusions

- This study has highlighted on the nutritive value of the stem bark and the mucilage extracted from fresh bark of the “white variety” of Byttneria catalpifolia. The extracts from the bark of this wild plant are characterized by high crude fiber and significant carbohydrates, proline, and vitamin B9 contents. The stem bark is a good source of minerals and should be consider as I, Ca and K rich food. The use of the stem bark powder would be more advantageous because it could contribute more to the nutritional requirement than the mucilage whose extraction does not capture all the minerals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This work was funded as part of the strategic project to support scientific research (Project PASRES N° 111). The authors are grateful to farmers of four villages (Zantongouin, Lema, Gan and Dingouin), located in the western part of Côte d’Ivoire, who contributed to the collection of the samples from the studied plants.

References

| [1] | Herzog, F.M. (1992). Étude biochimique et nutritionnelle des plantes alimentaires sauvages dans le sud du V-Baoulé, Côte d’Ivoire. Thèse, École Polytechnique Fédérale Zurich, Suisse. 134 p. |

| [2] | Shad, M.A., Nawaz, H, Rehman, T. and Ikram, N. (2013). Determination of some biochemicals, phytochemicals and antioxidant properties of different parts of Cichorium intybus L: a comparative study. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 23:1060-1066. |

| [3] | Bognon, C. (1988). Les végétaux dans la vie du people Wè (Côte-d'Ivoire). Thèse, Biologie végétale tropicale, Université de Paris VI. 291p. |

| [4] | Cristóbal, C.L. (2001) Taxonomía del género helicteres (sterculiaceae). Revisión de especies americanas. Bonplandia. 11: 1-206. |

| [5] | AOAC (1995). Official methods of analysis (15th ed.). Washington, DC: Association of AOAC international; Vols. I and II. 16th ed. |

| [6] | Bernfeld, P. (1955). Amylases α and β. Methods Enzymology. 1: 149-58. |

| [7] | Dubois, M., Gilles, K.A., Hamilton, J.K., Roben, F.A. and Smith, F. (1956). Colorimetric method for determination of sugar and related substances. Anal. Chem. 28:350-356. |

| [8] | FAO (2002). Food energy-methods of analysis and conversion factors, FAO Ed. |

| [9] | Mannar, M.G.V and Dunn, J.T. (1995). Iodation du sel pour l’élimination de la carence en iode. ICCIDD/IM/UNICEF/OMS. |

| [10] | Bouba A.A., Njintang N.Y., Foyet H.S., Scher J., Montet D., Mbofung C.M.F. (2012). Proximate Composition, Mineral and Vitamin Content of Some Wild Plants Used as Spices in Cameroon. Food Nutr. Sci. 3: 423-432. |

| [11] | Sahore, A., Kouame, M. and Nemlin, J. (2011). Physicochemical properties of some traditional vegetables in Ivory Coast: seeds of Beilschmiedia mannii (lauraceae), seeds of Irvingia gabonensis (irvingiaceae) and mushroom Volvariella volvacea. J. Food Technol. 9:57-60. |

| [12] | FAO (1986). Food composition table for use in Africa, FAO Ed. |

| [13] | Oulai, P., Zoue, L. and Niamke, S. (2015). Evaluation of nutritive and antioxidant properties of blanched leafy vegetables consumed in Northern Côte d’Ivoire. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 65:31-38. |

| [14] | Jenkin, D., Jenkin, A., Wolever, T., Rao A. and Thompson, L. (1986). Fiber and starchy foods: gut function and implication in disease. Am. J. Gastr. 81:920-930. |

| [15] | Ishida, H., Suzuno, H., Sugiyama, N., Innami, S., Todokoro, T., and Maekawa, A. (2000). Nutritive evaluation of chemical component of leaves stalks and stems of sweet potatoes (Ipomea batatas). Food Chem. 68:359-367. |

| [16] | Nacoulma, O., Piro, J. and Bayane, A. (2000). Study of the flocculating activity of a vegetable protein-mucilage complex in the clarification of raw water. J. Sci. Ouest Afr. Chim. 9: 43-47. |

| [17] | Osunde, Z.D. and Makama, M. (2007). Assessment of changes in nutritional values of locally sun-dried vegetables. Assump. Univ. J. Technol. 10(4): 248-253. |

| [18] | Askari, G., Eman-Djomeh, Z. and Mousari, S. (2009). An investigation of the effects of drying methods and conditions on drying characteristics and quality attributes of agricultural products during hot air/ microwave-assisted dehydration. Drying Technol. 27(7-8):831-841. |

| [19] | CTA, (2006). Centre Technique de Coopération Agricole et Rurale ACP-UE. |

| [20] | Nangula, P.U., Andre, O., Kwaku, G., Megan, J. and Mieke F. (2010). Nutritional value of leafy vegetables of sub-Saharan Africa and their potential contribution to human health: A review. J. food compos. Anal. 23:499-509. |

| [21] | Dias, M.I., Morales, P., Barreira, J.C.M., Oliveira, M.B.P.P., Sánchez-Mata, C. and Ferreira, I.C.F.R. (2016). Minerals and vitamin B9 in dried plants vs. Infusions: Assessing absorption dynamics of minerals by membrane dialysis tandem in vitro digestion. Food Biosci. 13:9-14. |

| [22] | Jaarsveld, P., Faber, M., Heerden, I., Wenhold, F., Rensburg, W.J. and Averbeke, W. (2014). Nutrient content of eight African leafy vegetables and their potential contribution to dietary reference intakes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 33:77–84. |

| [23] | Yang, W., Tan, B., Huang, D., Rautiainen, M., Shabanov, N.V., Wang, Y., Privette, J.L., Huemmrich, K.F., Fensholt, R., Sandholt, I., Weiss, M., Nemani, R.R., Knyazikhin, Y. and Myneni, R.B. (2006). “MODIS leaf area index products: From validation to algorithmim provement.” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44: 1885–1898. |

| [24] | Ejoh, A., Tchouanguep, M. and Fokou, E. (1996). Nutrient composition the leaves and flowers of Colocasia esculenta and the fruit of Solanum melongena. Plant. Foods Hum. Nutr. 49: 107-112. |

| [25] | Sobowale, S., Olatidoye, O., Olorode, O. and Akinlotan, J. (2011). Nutritional potentials and chemical value of some tropical leafy vegetables consumed in South West Nigeria. J. Sci. Multidiscip Res. 3:55-65. |

| [26] | Kris-Etherton, Hecker, K., Bonanome, A., Coval, S., Binkoski, A., Hilpert, K., Griel, A. and Etherton, T. (2002). Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. PubMed. 9:71-88. |

| [27] | Oulai, P., Zoue, L. and Niamke, S. (2015). Evaluation of nutritive and antioxidant properties of blanched leafy vegetables consumed in Northern Côte d’Ivoire. Pol. J. Food. Nutr. Sci. 65:31-38. |

| [28] | Oulai, P., Zoue, L., Megnanou, R-M., Doue, R., Niamke, S. (2014). Proximate composition and nutritive value of leafy vegetables consumed in northern Côte d’Ivoire. Eur. Sci. J.10 (6): 212 – 227. |

| [29] | Bouba, A.A., Njintang, N.Y., Foyet, H.S., Scher, J., Montet, D., Mbofung, C.M.F. (2012). Proximate Composition, Mineral and Vitamin Content of Some Wild Plants Used as Spices in Cameroon. Food Sci. Nutr. 3:423-432. |

| [30] | Adhikari, B.M., Bajracharya, A. and Shrestha, A.K. (2016). Comparison of nutritional properties of Stinging nettle (Urticadioica) flour with wheat and barley flours. Food Sci.Nutr.4:119-124. |

| [31] | Turan, M., Kordali, S., Zengi, H., Dursun, A. and Sezen, Y. (2003). Macro and micro mineral contents of some edible leaves consumed in Eastern Anatolia. Plant Soil Sci., 53: 129-137. |

| [32] | Adeyeye, E. and Aye, P. (2005). Chemical composition and the effect of salts on the food properties of Triticum durum whole meal flour. Pak. J. Nutr.4:187-196. |

| [33] | Taga, I., Sameza, M., Kayo, A. and Ngogang, J. (2004). Évaluation de la teneur en iode des aliments et du sol de certaines régions du Cameroun. Cahiers d'études et de recherches francophones / Santé. 14 (1): 11-5. |

| [34] | Delange, F. (2001). La Thyroïde: Des concepts à la pratique clinique. Elsevier, Paris. 355-362. |

| [35] | Ahad, F., Ganie, S.A. (2010). Iodine, Iodine metabolism and Iodine deficiency disorders revisited. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 14(1): 13–17. |

| [36] | Mannar, V.M.G. (1996) SOS for a Billion, the Conquest of Iodine Deficiency Disorders. In: Hetzel, B.S. and Pandav, C.S., Oxford University Press, New Delhi. 99-118. |

| [37] | Assoumanou, G.M., Zohoncon, T.M. and Akpona, S.A. (2011). Evaluation de la teneur en iode des sels de cuisine dans les ménages de deux zones d’endémie goitreuse du Bénin. Int. J. of Biol. Chem. Sci. 4:1515-1526. |

| [38] | Mamane, N.H., Sadou, H., Alma, M.M. and Daouda, H. (2013). Evaluation de la teneur en iode des sels alimentaires dans la communauté urbaine de Niamey au Niger. J. Soc. Ouest-Afr. Chim. 35:35-40. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML