-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2017; 7(2): 29-34

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20170702.01

Risk Factors for Overweight and Obesity in Private High School Adolescents in Hawassa City, Southern Ethiopia: A Case-control Study

Anjulo H. Bereket1, Mesfin Beyero2, Alemayehu R. Fikadu3, Tafese Bosha3

1Department of Nursing, Hawassa Health Science College, Hawassa, Ethiopia

2Consultant, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

3School of Nutrition, Food Science and Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa

Correspondence to: Anjulo H. Bereket, Department of Nursing, Hawassa Health Science College, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Prevalence of overweight and obesity has been increasing especially in urban adolescents from developing countries including Ethiopia. Finding out risk factors is an important step towards prevention of overweight and obesity. Therefore, this study was designed to identify risk factors of overweight and obesity among private high school adolescents in Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia. A case-control study was conducted on 324 private high school adolescents in Hawassa from February to March 2016. The cases were overweight and obese adolescents, while controls were the normal ones. Height and weight were measured following standard procedures. Pretested structured questionnaire was used to collect data on socioeconomic and demographic factors. Dietary practice was assessed using food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) was employed to examine physical activity level. Females accounted 48% of control, and 60% from case groups. The mean (SD) age of control adolescents was 17.18(1.32), and that of cases was 16.93(1.25). Being female (AOR= 1.66; 95% CI: 1.001-2.75), increased monthly income, ≥20,000 Birr, (AOR= 2.88; 95% CI: 1.14-7.29), and higher level of maternal education were found to be risk factors for overweight and obesity among study participated adolescents. Compared to the ones who consumed ≥7 times/week, adolescents who ate fruits for 1-4 times/week were 2.16 times more likely to be overweight and obese. Those who consumed vegetables less than 1 time in a week had odds of 6.0 to be overweight and obese. Adolescents having ≤3 meals/day were almost two times more exposed for overweight and obesity (AOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.09-3.48). The results were consistent with the previous findings of other scholars.

Keywords: Overweight and obesity, Risk factors, Adolescents, Private high schools, Hawassa City

Cite this paper: Anjulo H. Bereket, Mesfin Beyero, Alemayehu R. Fikadu, Tafese Bosha, Risk Factors for Overweight and Obesity in Private High School Adolescents in Hawassa City, Southern Ethiopia: A Case-control Study, Food and Public Health, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 29-34. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20170702.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Overweight and obesity is defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation which may impair health [1]. Prevalence of overweight and obesity has been increasing in adolescents over the last few decades in Africa [2]. Currently, about 20-50% of the urban population in Africa is classified as either overweight or obese, and by 2025, 3/4th of the obese population worldwide will be in non-industrialized countries [3]. Ethiopia is one of the low income countries showing experience of a shift from underweight to overweight and obesity particularly in urban settings [4, 5]. Obesity is the 5th leading global risk for mortality [6], and has substantial impact on young age reducing life expectancy [7]. The first step in prevention and management of overweight and obesity is identifying risk factors contributing for overweight and obesity. Therefore, the authors designed this study to identify risk factors of overweight and obesity in private high school adolescents in Hawassa City, Southern Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

- This study was conducted in private high schools in Hawassa which is capital of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region in Ethiopia. The area is located 275 km south from Addis Ababa at 07° 03' north latitude and 30° 29' east longitude [8]. According to the city administration education office, there were 15 private and 13 governmental high schools in Hawassa. The total number of adolescents was 18768 (9588 males and 9180 females), and 7834 (4191 males and 3643 females) respectively in government, and private high schools.

2.2. Study Design

- A case-control study was conducted from February to March 2016 with the cases being overweight and obese, and with controls being normal adolescents. The source population for this study was all adolescents in private high schools in Hawassa. Study population was randomly selected private high school adolescents in age range of 14 - 19 years who satisfy the definition of case and control. Sample size of 335 was calculated using EPI Info version 7.0 with assumptions of 80% power, 95% confidence level and controls to cases ratio of 2.0, to detect at least 2 odds ratio differences between the cases and controls [9]. Five private high schools were selected from 15 in the city using simple random sampling technique. Study participants were selected by proportion to population size (PPS) technique. Weight and height of the study participants were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight in kilogram divided by height in meter square. The age and sex specific BMI values in the range of 5th - 85th percentile considered as normal, 85th - 95th overweight, above 95th obese [10].

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Private high school adolescents with sex and age specific BMI above 5th percentile were included in this study. The ones with physical disabilities, pregnant, and those who were on medications for chronic diseases were excluded.

2.4. Variables

- The dependent variables were overweight and obesity, while independent ones were socioeconomic factors (occupation and income level), demographic factors (sex, age, family size, and marital status), parental educational, dietary habit of adolescents (meal frequency, skipping breakfast, consumption of fruits, vegetables, fried foods, snacks, soft drink, and alcohol), physical activity level, birth order, and breast feeding during childhood.

2.5. Data Collection

- Structured questionnaire was prepared in English, and translated to Amharic. Data collectors were trained, and pre-test was conducted by 5% of the sample size. Data collection was supervised by the principal investigator. Data completeness was checked, and cleaned. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.5 kg using Unicef Seca 700 weighing scale, and height to the nearest 0.1 cm with Shorr sliding length measuring board. Socio-economic and demographic characteristics were studied using structured questionnaire. Food frequency questionnaire was used for dietary assessment. GPAQ [11] was employed to assess physical activity.

2.6. Data Analysis

- Data analysis was carried out using SPSS for windows ver. 20.0. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine association between potential categorical factors. Independent sample t-test was employed for continuous variables to find out any significant differences between the mean values of the cases, and controls. The odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed for each significant categorical factor, and continuous data using binary logistic regression. To control confounders, variables with p-value <0.25 in bivariate analyses were taken to multivariable logistic regression analyses. A factor with an OR significantly (p<0.05) higher than 1.00 was taken as a risk factor for adolescent overweight and obesity, while OR significantly (p<0.05) less than 1.00 was considered as a protective factor. In the independent sample t-test, a factor with the p-value <0.05 was considered as significant, but > 0.05 was insignificant. The goodness of fit of the final logistic regression model was checked using the Hosmer-Lemeshow technique, in which a p-value >0.05 indicates a good model.

2.7. Ethical Consideration

- Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Hawassa University. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants before data collection. Overweight and obese adolescents were advised after data collection.

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics

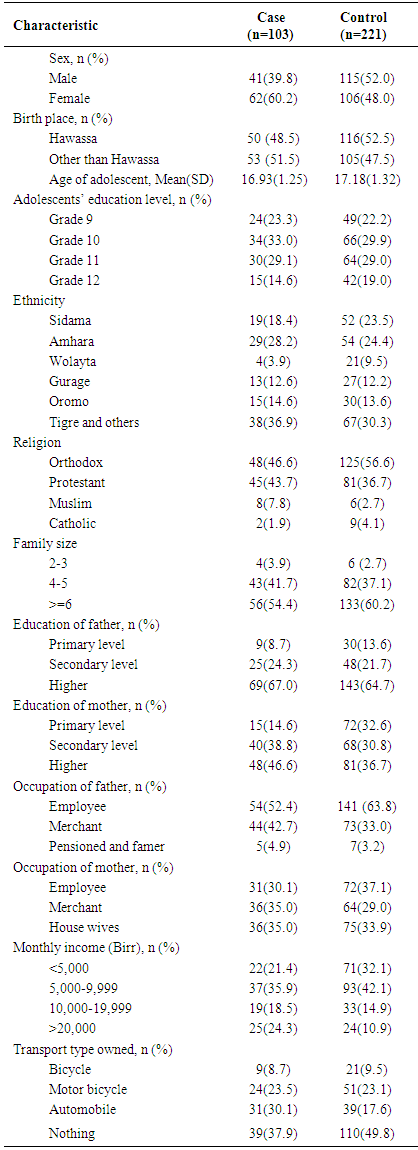

- A total of 324 private high school adolescents (103 cases and 221 controls) were participated in this study with response rate of 97%. Females accounted 60.2% in cases, and 48% in control. Mean age of the adolescents in cases was 16.93(1.25), and 17.18(1.32) in control. Majority were Orthodox religion followers. About 47% of the mothers in cases, and 37% in control attended higher education respectively. More than half of fathers attended higher level education, and employed. About 34% and 35% of mothers, respectively in controls and cases, were house wives (Table 1).

|

3.2. Dietary Practice of Study Participants

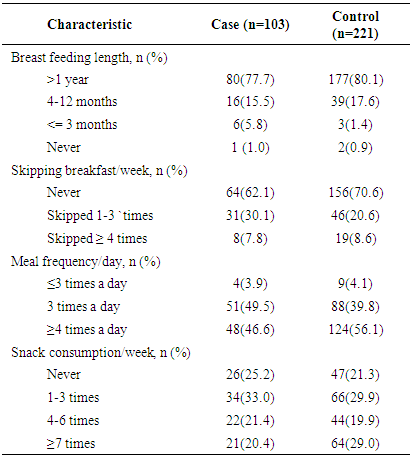

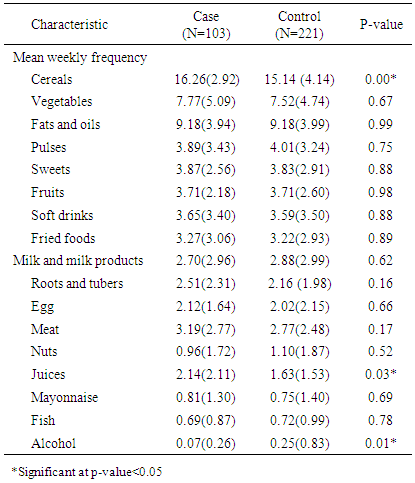

- Majority of the adolescents in both categories were breast fed in their childhood for above a year. More than half never skipped their breakfast in the week preceding the survey in both groups. More than half of the adolescents in control category had meal ≥4 times a day. There was statistically significant difference in mean consumption of cereal (p=0.02), juice (p=0.03) and alcoholic beverages (p=0.01) in the week preceding the survey between cases and controls. (Table 2 and 3).

|

|

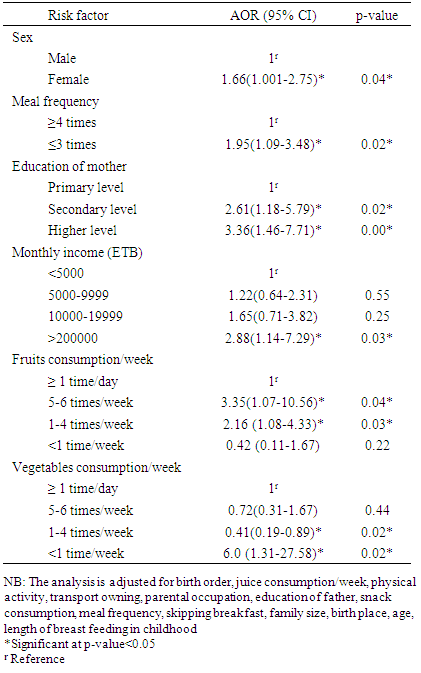

3.3. Risk Factors of Overweight and Obesity in Private High School Adolescents in Hawassa

- The multivariable analysis proved that an odd of being female in cases was 1.66 times higher than odds of being female in controls (AOR=1.66; 95% CI: 1.001-2.75). Odds of mother’s who attended secondary, and higher level education were 2.6, and 3.4 folds (AOR= 2.61; 95% CI: 1.18-5.79, and AOR= 3.36; 95% CI: 1.46-7.71 respectively) higher respectively in cases than odds of mother’s who attended secondary and higher education in controls. Odds of earning monthly income ≥20,000 Birr was 2.9 times higher (AOR= 2.88; 95% CI: 1.14-7.29) in cases than odds of earning monthly income ≥20,000 Birr in controls. Odds of consuming fruits 1-4 times/week were 2.16 times higher (AOR=2.16, 95% CI: 1.08-4.33) in cases than odds of consuming fruits 1-4 times/week in controls. An odd of consuming vegetables less than 1 time/week was 6 folds higher (AOR=6.0, 95% CI: 1.31-27.58) in cases than control. An odds of having ≤3 meals/day was almost 2 times higher in cases than odds of having ≤3 meals/day in controls (AOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.09-3.48) (Table 4).

|

4. Discussion

- This study found that being female is a risk factor for adolescent overweight and obesity. The findings of cross sectional studies conducted on Ethiopian adolescents by Teshome et al [4], and Gebreyohannes et al [12] support the current result. However, a case control study on Brazilian adolescents reported the reverse [13]. Another case control study by Bhuiyan et al. on urban school children and adolescents in Bangladesh reported even no significant association between sex and overweight and obesity [10]. The observed increase in odds of female adolescents to be overweight and obese may be attributable to their reduced physical activity level, and less healthy dietary practice. Study from Brazil and Kenya reported effect of birth order, concluding that being first child [13, 14], and last child [14] exposes for overweight and obesity in adolescence. This inclines to be true in the current study too even though it was not statically significant. The lack of statistical significance may be due to increased homogeneity of the sampled population. Even though not statistically significant, it deemed that adolescents who were breast fed below 12 months in childhood were at higher risk for overweight and obesity compared to their counterparts fed for ≥ 12 months (COR: 1.12). The observed absence of association between length of breast feeding and overweight and obesity in adolescents might be due recall bias. Another explanation is that majority (80%) of adolescents in control, and (78%) in case categories were breast fed in their childhood for ≥12 months, so that this increased homogeneity might have also masked the associations. Different literatures showed a controversial association between history of breast feeding in childhood, and overweight and obesity in adolescents. For instance, report by Mohammadreza et al. [15] supports the current finding. However, meta-analysis suggested that breastfeeding has a significant protective effect against obesity in children [16, 17]. Renata and Carlos in 2007 found that the risk of obesity in children that had never been breastfed was twice that of other children [18]. Andrej et al. in 2008 reported that for 15-year old children from the group with the shortest breastfeeding duration had the highest values of BMI [19]. Place of birth, family size, and religion were not found to be risk factors in the current study. The present study found that fathers’ education is not risk factor for overweight and obesity in adolescents participated in the study. However, being born from mother who attended secondary, and higher level education compared to primary level, explained overweight and obesity in adolescents. This may be attributable to the busy schedule of educated mothers for instance with office works so that couldn’t make healthy food choices for their adolescents and family. In addition, the observed high level education might have helped mothers to be employed, and increased their household income. This finding is in line with that of Alwan et al. who noted that overweight and obesity were more common in children whose mothers attended higher level education [20]. A contradicting finding was reported from Tanzania by Shayo and Mugusi in 2011 who showed that prevalence of obesity was higher in adolescents whose mothers had no formal education (26.4%) compared to those with primary (19.5%), secondary (14.2%) and postsecondary education (20.9%) [21]. Increased monthly income of the households, for instance ≥20,000 Birr predicted overweight and obesity in adolescents involved in the present study. This may be attributable to the change in life style, and dietary pattern associated with increased income. The current finding is in line with many from different countries for example from Ethiopia [4, 12, 22], Tanzania [21], Bangladesh [10], and Japan [23]. However, scholars from developed countries reported contradicting results. Skipping breakfast wasn’t found to be a risk factor for overweight and obesity in adolescents participated in this study. This is in agreement with the report from Brazil [13]. Meal frequency ≤3 times/day was found to be a risk factor for overweight and obesity. This is supported by BT House et al. (2014) who noted that increased eating frequency is linked to decreased obesity and improved metabolic outcomes [25]. However, Novaes et al from Brazil reported that children who consumed snack frequently were at higher risk of being obese [24]. The observed similarities in dietary practices between controls and cases in the current study participants may be due to the homogeneity of the study population, and the peer influence. Decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables were identified to be risk factors of overweight and obesity in adolescents. For instance, adolescents who consumed fruits for 1-4 times/week were 2.16 times more exposed for overweight and obesity compared to the ones consumed 7 times/week. Odds of consuming vegetables less than 1 time/week in cases were 6 times higher than odds of consuming vegetables less than 1 time/week in control group. This finding goes in line with that of other scholars [4, 13, 26, 27]. Reduced physical activity was seen as a risk factor for adolescent overweight and obesity during univariable analysis, but the significance was lost in multivariable analysis. This finding is in line with the report from a cross sectional study conducted in Addis Ababa [12]. Christina in 2009 also reported absence of association between physical activity level and overweight and obesity in adolescents [28]. The observed absence of association between physical activity and overweight and obesity in current study may be attributable to the homogeneity of sampled population, and change in their life style. Limitation of the study• This study considered only private high schools in Hawassa City, which might have masked significant differences in some variables.• GPAQ which seems appropriate for adults was used for adolescents.

5. Conclusions

- This study demonstrated that being female, low consumption of fruits and vegetables, having ≤3 meals/day, high monthly income, and increased maternal education were found to be risk factors for overweight and obesity in private high school adolescents in Hawassa City.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank the study participants, and data collectors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML