-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Food and Public Health

p-ISSN: 2162-9412 e-ISSN: 2162-8440

2015; 5(6): 213-219

doi:10.5923/j.fph.20150506.02

Impact of a Comprehensive Intervention on Food Security in Poor Families of Central Highlands of Peru

J. Castro , D. Chirinos

Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Perú

Correspondence to: J. Castro , Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Perú.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Being child nutritional status the impact variable, food and nutritional security elements included interactions between social, demographic, productive, and health conditions among others and the comprehensive intervention assessed changes in availability, access, utilization and stability over time. Aims: Assess the impact of a comprehensive intervention on food and nutritional security in families with children less than 5 years in Andean communities of central Peru. Method: A pre experimental pre-post study was realized. The first measurement corresponded to baseline and the second to the end line, after 3 intervention years. The information was processed in SPSS V.16.0. Results: Before the intervention stunting and anemia prevalence were 45.57 and 61.38%, respectively, after 3 years decreased by 6.37 and 8.71%, respectively. Diarrhea was reduced from 39.3 to 33.8%. Families implemented organic gardens, greenhouses and raising guinea pigs, improving their feeding practices, health and housing conditions. Conclusions: the comprehensive intervention allowed to reduce the prevalence of chronic malnutrition, anemia and diarrhea in children under 5 in 6 districts of Junin as well as to improvement other indicators of health and personal hygiene, housing conditions and other aspects related to family food production. Beneficiary families have increased consumption and food production (home gardens, greenhouses, and breeding of guinea pig and poultry) and improved kitchen conditions and housing. The logical framework responds to their purposes and participatory process was the essence of its success.

Keywords: Nutritional intervention, Food and nutritional security, Nutritional surveys, Stunting, Anemia

Cite this paper: J. Castro , D. Chirinos , Impact of a Comprehensive Intervention on Food Security in Poor Families of Central Highlands of Peru, Food and Public Health, Vol. 5 No. 6, 2015, pp. 213-219. doi: 10.5923/j.fph.20150506.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since the 1960s, the fight against child malnutrition relied on welfare approaches of little impact. Food and Nutrition Security in theory and practice has evolved significantly in recent decades [1], being child nutritional status the nutritional system impact variable [2]. Recently, food security term applies to local level, family or individual level. Including food supply, access, and vulnerability, and sustainability [3]. The conceptual framework of food and nutritional security considers three physical elements and one temporary: availability, access, utilization and stability or sustainability [4].Availability refers to food physical existence (own production and markets). Access is ensured when families and their members have resources to obtain appropriate foods for a nutritious diet. The food biological utilization refers to body's ability to ingest, digest and use food for everyday activities or store energy. Stability is the temporal dimension of nutrition security [3]. Food availability depends on family production, diversified production and market supply, being the availability, in rural areas, related to access. Another determinant refers to environmental conditions; safe water availability, sanitation and safe environment, including housing, whose improvement reduces the presence of diarrhea and intestinal worms [5].The intervention focuses on food security at household and individual level, considering to child nutritional status as the variable effect [6, 7]. The health status allows appropriate food use, is affected by adequate health care for mothers and children, and access to health services [8].Food and nutrition security must be evaluated in order to determine the nature, extent and causes of food and nutrition insecurity. Findings allow us to design holistic interventions, with baseline, monitoring and evaluation indicators which assesses changes over time as well as program impact [2, 7]. Agricultural production and technology indicators are evaluated [9]. Intra family food distribution, feeding practices, diarrhea prevalence, acute respiratory infections, access to clean and safe water, environmental hygiene, use of latrines, waste dumps, etc. are evaluated too [10].The malnutrition-driven factors include interactions between social, demographic, genetic, infectious and social conditions [11, 12]. Planning and implementing comprehensive public health schemes to prevent and alleviate child malnutrition as well as integrated and holistic interventions is required in this area.To measure the nutritional status, we used anthropometric techniques [2, 13-16], and hemoglobin measurements [17]. These anthropometric indices were calculated in the Anthro V 3.2.2 [18] and compared with the new 2006 WHO Growth Pattern, which is the result of the multicenter study [19-22]. In Peru, at the end of the 90s, promotional preventive approaches were introduced. The external assessment of the "Good Start" program reported a reduction of stunting and anemia of 4.3 and 5.9 % per year [23]. Another integral intervention applied in highland communities was the "Heart Family" in Cuzco, Huaraz and Ayacucho which allowed a reduction in the incidence of chronic malnutrition in more than 50 % in 15 years of operation [24]. Participants made family development plans, redesigned their homes, implemented organic gardens, increased animal husbandry and applied modern irrigation. Therefore they improved food availability and access as well as sewage disposal systems and home piped water [24, 25]. The aim of this research was to determine the impact of a comprehensive food security and nutrition intervention developed over three years (March 2008 to March 2011) in 450 poor rural families with children under 5 years of the Junin region, located in the central highlands of Peru, on chronic malnutrition and indicators of availability, access and use of food. These families are mainly characterized by developing agricultural activities, poor education, inadequate productive resources and low technology for food production.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Type and Place of Study

- A pre experimental pre-post study was performed. The first measurement corresponded to the Baseline 2008 and the second to the End line of 2011. The intervention was conducted in rural families in 12 communities in 6 districts (Pancan, Huamali, Chambará, Quilcas, Acobamba and Tapo) of Junin Region; located between 3300-3600 masl, whose main activity is agriculture.

2.2. Population and Sample

- The whole intervention was performed in 450 rural families with children less than 5 years, which corresponds to a baseline beforehand determined. The closing evaluation was applied to 100 families who had a continuing involvement during the three years of intervention. The sample size was determined considering the public nutrition recommendations for community studies [16], which is used when the baseline prevalence is known and changes after the intervention are expected. The sample corresponds to 6 districts according to the number of beneficiaries in a community.

2.3. Comprehensive Intervention

- Strategies including availability, access and food usage along with participatory methodologies were applied in order to increase family production by using sustainable agricultural technologies and local resources and family knowledge by improving hygiene and health conditions which result in best practices in maternal child health and nutrition. An agricultural production demonstration center was implemented with tutorial-training workshops, internships, modern irrigation systems, organic gardens, whole farms, improved breeding of guinea pigs, cultivated pastures installation as well as nutritional and health education workshops for mothers, improved stoves, and composting toilets.

2.4. Baseline and End-line

- Baseline and end-line surveys were applied in households. The surveys were designed and validated according to the logical framework indicators of the program [26, 27, 21]. The evaluation considered data about the following variables: availability, access, consumption and use of food [16], as well as hemoglobin and anthropometric measurements. In each household, healthy living, organize gardens, upbringing and family farms, sewage and garbage disposal, hand washing and toilet corner among others were verified. For data collecting, interviewers were trained and the teams were standardized.

2.5. Anthropometric Assessment and Hemoglobin Determination

- The children were weighed on a digital scale SECA - Unicef and height were measured in a properly standardized wooden mobile rod [13, 28, 29]. Hemoglobin was determined using a portable hemoglobin meter (HemoCue) following the recommended protocol [30, 31]. Anthropometric indices as Z scores were compared with the new international Child Growth Standards WHO-2011 [19, 21, 22], determining the nutritional status of children under 5 years in the Antrho v.3.2.2 [18].

2.6. Information Systematization

- After validating data consistency, change rates between the end-line results and baseline were compared, using the SPSS v.16.0 and Excel. To determine the effect of the intervention on the prevalence of stunting and anemia, tests "t" to mean difference in independent samples was performed. Previously the percentage values were transformed angularly [32]. The values determined in each of the 6 districts involved in the intervention were considered as replicates.

2.7. Ethical Aspects

- The study protocol was assessed and registered by the Research Center of the National University of Central Peru, who also has functions of Ethics Committee. Survey objectives and assessment, stressing their voluntary and confidential participation were explained to all mothers participating in the study, who signed a consent form elaborated on the basis of specific codes of ethics for this type of study and validated by the graduate program in Food Security and Nutrition.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Families at the End of the Intervention

- The average age of the mothers was 32.33 years (17-55 years). The father age was 36.48 years (23-62 years). The educational level of the father is mostly secondary education (41%) and elementary education (28%) and mothers, elementary education (46%) and secondary education (45%). The 61% were cohabiting and 27% married. Of the 100 children under 5, assessed at the closing line, 56 were males and 44 females. The average age was 32.77±15.72 months. Families had 1.35±0.57 children under 5 years (1 to 4), regarded in study the younger child. Families in total were between 1-9 sons, and of children under 5 years included in the study, 29 were the firstborn, 26 the second, 17 the third, 11 the fourth, 8 the fifth, 4 the sixth, 3 the seventh, 1 the eighth and 1 was the ninth child.

3.2. Impact of the Intervention on Chronic Malnutrition and Infant Anemia

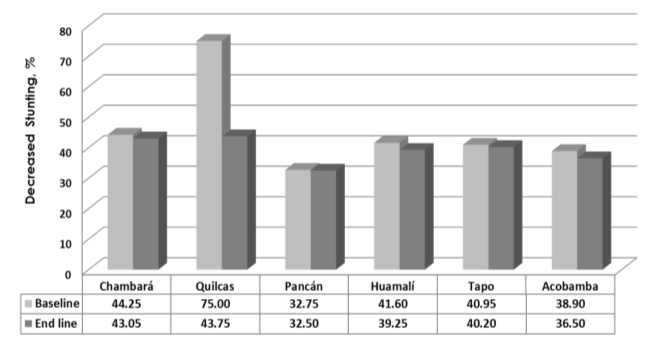

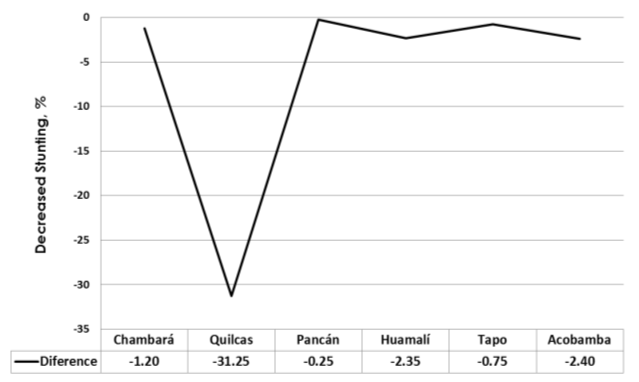

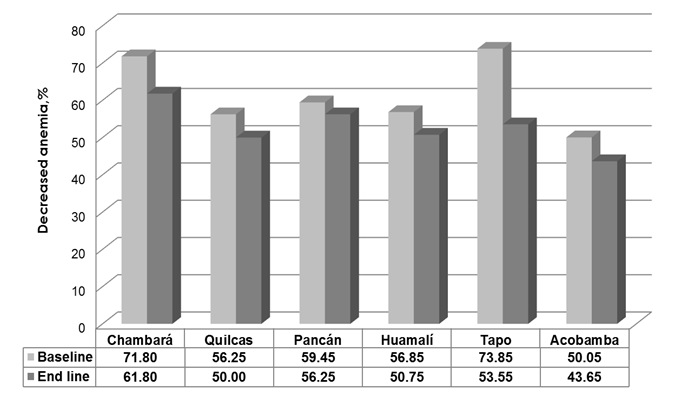

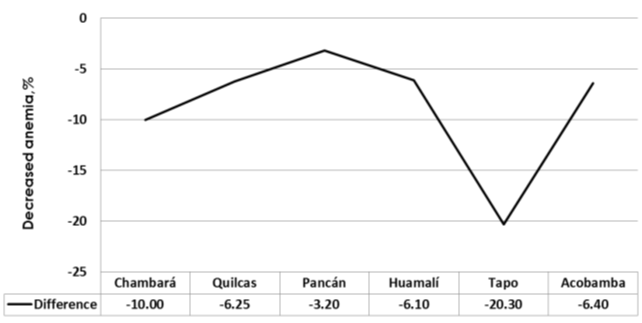

- Before the intervention, the stunting and anemia percentage in children under 5 in the 6 districts were: Chambara 44.25% and 71.80%, Quilcas 75.00% and 56.25%, Pancan 32,75% and 59.45%, Huamali 41.60% and 56,85%, Tapo 40.95% and 73.85%, Acobamba 38.9% and 50.05% correspondingly. The overall averages of stunting and anemia before surgery were 45.57% and 61.38%, respectively. After the intervention rates of stunting and anemia in children under 5 were: Chambara 43.05% and 61.80%, Quilcas 43.75% and 50.00% Pancan 32.50% and 56.25%, Huamali 39.25% and 50.75%, Tapo 40.2% and 53,55%, Acobamba 36.5% and 43.65%, correspondingly. On average, stunting and anemia at the end of the intervention were 39.21 and 52.67 %, respectively (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4).

- On average, the implementation of the comprehensive intervention allowed a reduction of 6.36 (45.57 to 39.21%) percentage points in the stunting prevalence (p=0.339) and 8.71 (61.38 to 52.67%) percentage points in anemia prevalence (p=0.087), demonstrating a positive impact of the intervention in reducing these indicators.

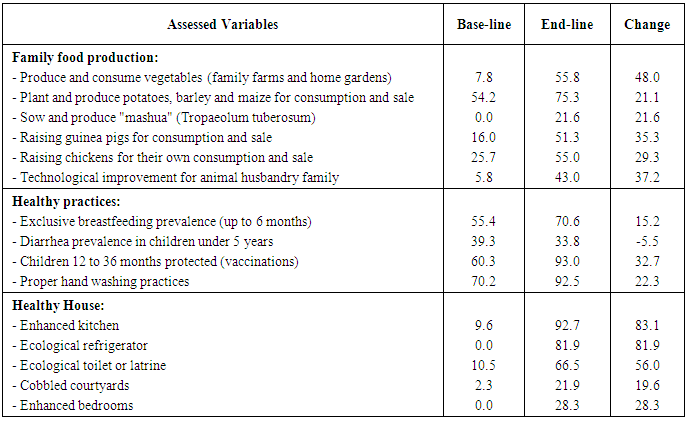

3.3. Impact of the Intervention on Productive, Feeding Practices and Health

- The implementation of comprehensive intervention for three years allowed Junin rural families to improve the use of appropriate technologies in food production, by diversifying food production and improving their nutritional status, their feeding practices and health care as well as hygiene and sanitation practices at home (Table 1).

4. Discussion

- In the first decade of this century, our country has been marked by malnutrition, poverty and exclusion, especially in rural areas of the mountains and jungle. Social, food and nutrition situation is summarized in a strong disparity; stunting in 2012 was 18.1%33, that is, one in five children under 5 suffer from stunting; however this average masks extreme situations, for example in Tacna region, the stunting was 3.1%, while in Huancavelica was 50.2%. In Junin the stunting was 24.4% in 2011 [33]. On the other hand the problems of food insecurity in mountain farm families are increasingly alarming, because their daily diet is based mainly on the little food they produced or obtained as compensation of their farm labors; intake rich in carbohydrates and low in protein and micronutrients [26, 27].In the present study, we found low-income families with a low level of knowledge about nutrition and food in the 6 districts evaluated. They have food insecurity problems, typical of poor families [26, 27, 12]. The intervention was improved as the activities leading to the development of productive capacities were performed (Table 1). It also improved health and nutrition practices, hygiene and sanitation, and participatory capacity.After end-line evaluating, evidence suggests that the comprehensive intervention had a positive impact, both reducing stunting and anemia in children (Figures 1,2,3,4) and playing an important role in changing attitudes about child and housing. Feeding practices as well as the usage of agricultural production technologies based on the resources and potential of each area were improved. Vegetables have been incorporated in nutrition, especially those growing in vegetable gardens and greenhouses. The consumption of mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) an Andean tuber has increased. Crops have been diversified and improved breeding guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus), small Andean rodent histricomorf which had high protein (20.3%), with low saturated fat and high economic value. Poultry have been improved. Healthy housing has been improved (Table 1). In short, the comprehensive intervention improved the availability, access and use of the food, which was reflected in improving child nutritional status, variable impact of family food and nutrition security [2, 16, 12].One of the essential components of nutritional food system in a rural area is food production which is directly linked to the availability and access to food [7], therefore the nutritional interventions should consider strengthening productive capacities of protein foods and micronutrients for incorporating in daily diets, especially in child food [26, 27].The implementation of home gardens and greenhouses has allowed children to eat vegetables and salads, improving their intake of protective foods, at least once a week they consume guinea pig meat. Families have improved food production techniques after having participated in the training programs and training and exchange of experience with families of higher technological level.Another important aspect is that the beneficiaries indicated that due to the intervention, they had improved their family income. They have more and better products for their own consumption and sale, improving not only the availability but access as basic components of the conceptual model of nutritional food security [7]; They said they have more resources for food assistance, health care and education of their children after reducing the household head economic dependence.The life quality of families involved in the intervention has improved. These results related to other successful experiences as reported by PRISMA [34], which observed that having one toilet helps reduce diarrheal diseases. In the same way, in Ayacucho the "Integrated Health Project" trained families in the use and maintenance of squat holes installed near their homes, therefore, infant diarrhea decreased from ten to two episodes (each year), and the diarrhea prevalence was reduced from 75% in 2009 to 25% in 2010. CARITAS Loreto [35] reports similar experiences due to household access to basic sanitation, safe water Safe and proper disposal of excreta, which has decreased the risk of infectious diseases such as diarrhea, parasites and skin infections which were very common in this area. In Trompeteros, families that had an adequate sewage disposal increased from 7% to 25%. In Loreto, "Healthy Families in Indigenous communities in the basins of the Pastaza, Corrientes and Tigre rivers" project was performed in Loreto, where properly excreta disposal increased from 3% to 26%. There people organized Water and Sanitation Administration Boards for water system maintenance and quality assurance. Stunting prevalence decreased by 8% (27% to 19%) in 3 years; anemia was reduced by 8.7%. CARITAS Ancash [36] evaluated another successful project, “Ally Micuy”, for families with children under three and pregnant women. It was found that episodes of diarrhea decreased from 29.8% to 22.5% from 2007 to 2010; while diarrhea decreased from 46.9% to 41.7%. Improvements in health care and housing cleaning lead to a reduction in morbidity and mortality and improve nutritional status [5, 12], because the conditions that lead to stunting results from the limited access to health services, safe water, sanitation and food as well as from bad practices in child care [37].Our results confirm that "food security is achieved when adequate food (quantity, quality, safety and socio-cultural acceptability) is available, accessible and successfully used by all individuals at any time in order to achieve a proper nutrition for a healthy and happy life” [3, 4]. In this definition, we stress the stability of the availability, accessibility and use of food considering as the impact variable, stunting prevalence, has adverse effects on human brain development and intellect and undermine the ability to work and productivity due to the illness, reducing productivity at work, and total number of years of work during the life [7].Reducing malnutrition depends not only on physical factors, such as increased food availability and accessibility by means of capacity building strategies to improve local and household food production, but other factors designed to optimize child development and child accessibility to health and nutrition. Therefore, our findings confirm that the etiology of malnutrition responds to social, demographic and cultural interactions as well as health practices, among others [12].

5. Conclusions

- The comprehensive intervention allowed reducing the prevalence of stunting, anemia and diarrhea of children in poor families of central highlands of Peru as well as improvement to family food production and other indicators of health and personal hygiene, and housing conditions. Beneficiary families have increased consumption and food production (home gardens, greenhouses, and breeding of guinea pig and poultry) and improved kitchen conditions and housing.Among the most important lessons are the participation of all actors, and responsible work of the facilitators and timeline completion. The development of local capacity through community-based participatory actions improved the program outcome. On the other hand since intervention was successful in the fight against poverty and child malnutrition in the central highlands, it should be replicated and applied to nearby communities. Although the level of anemia has been greatly reduced, this situation still is a public health problem in participating populations; therefore actions to reduce it must be implemented.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- To rural families of the six districts, for their voluntary participation and active in the study. To the field team, for their responsibility, enthusiasm, patience and commitment, and shared experiences in these three years of intervention. To the authorities of the communities involved in the intervention. To the team of the Graduate Program on Food Security and Nutrition of the National University of Central Peru.

References

| [1] | Haddinott J. Operationalizing household food security in development projects. Technical Guide Nº 1, Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. 1999. |

| [2] | Gross R. Nutrition and the alleviation of absolute poverty in communities: concept and measurements, in: Nutrition and poverty, Papers from ACC/SCN 24th Session Symposium Kathmandu, March 1997, ACC/SCN Policy. 1997. Paper #16:p. 95-103. |

| [3] | Hanh H. Conceptual Framework of Food and Nutrition Security Programmes. Beitrag. Zum Seminar der DSE/ DWHH/ GTZ Nutrition and Food Security. GTZ. 2000. |

| [4] | FAO. World Food Summit. FAO Corporate Document Repository. 1996. |

| [5] | Billing P, Bendahmane D, Swindale A. Water and Sanitation Indicators Measurement Guide. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance. United States Agency for International Development, USAID. 1999. |

| [6] | Gross R, Schultink W, Kielmann AA. Community nutrition: definition and approaches. In: Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition. Editors: Sadler MJ, Strain JJ, Caballero B (eds.) Academic Press Ltd, London. 1999, 433-441. |

| [7] | Gross R, Schoeneberger H, Pfeifer H, Preus HJ. The four dimensions of food and nutrition security: Definition and Concepts. Internationale Weiterbildung und Entwicklung GGmbH. FAO. 2000. |

| [8] | Smith L, Haddad L. Explaining child malnutrition in developing countries: a cross country analysis, FCND discussion paper No. 60, Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. 1999. |

| [9] | Slack A. Food and Nutrition Security Data on the World Wide Web, Technical Guide No 2, Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. 1999. |

| [10] | Ojha DP. Impact Monitoring-Approaches and Indicators. Experiences of GTZ sup-ported multi-sectoral rural development projects in Asia. Div.45 Rural Development, GTZ Eschborn. 1998. |

| [11] | Haddad L, Kennedy E, Sullivan J. Choice of indicators for food security and nutrition monitoring. Food Policy. 1994;19(3): 329-343. |

| [12] | Manary MJ, Solomons NW. Public health aspects of undernutrition. In: Public Health Nutrition. The Nutrition Society Oxford. 2004. |

| [13] | WHO. Measuring change in nutritional status: Guidelines to assess the nutritional impact of supplementary feeding programs for vulnerable groups. World Health Organization. Ginebra. 1983. |

| [14] | WHO. Physical Status: The use and Interpretation of anthropometry, Report of a World Health Organization expert committee, WHO Technical report Series 854, Geneva. 1995. |

| [15] | Gibson, R. Principles of Nutritional Assessment. Oxford: Oxford Press. 2005. |

| [16] | Gross R, Kielmann A, Korte R, Schoeneberger H, Schultink W. Guidelines for Nutrition Baseline Surveys in Communities. SEAMEO-TROPMED and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). Bangkok: Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, Suppl. 1997. |

| [17] | Guillespie S. Major Issues in the Control of Iron Deficiency. The Micronutrient Initiative. Ottawa, New York: MI, UNICEF. 1998. |

| [18] | WHO-Anthro V.3.2.2. World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/.Acceded July 22, 2011. |

| [19] | Garza D, de Onís M. Estudio Multi-centro sobre las Referencias del Crecimiento de la Organización Mundial de la Salud; 2006. |

| [20] | OMS. El Estudio Multi-centro de la OMS de las Referencias de Crecimiento: Planificación, diseño y metodología. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. The United Nations University. 2006; vol.25, No.1, S15-S26. |

| [21] | Chirinos D, Castro J. Comparison of NCHS-1977, CDC-2000 and WHO-2006 Nutritional Classification in 32 to 60 month-old Children in the Central Highlands of Peru (1992-2007). Universal Journal of Public Health. 2013;1(3):143-149. |

| [22] | Castro J, Chirinos D. Z-Score Anthropometric Indicators Derived from NCHS-1977, CDC-2000 and WHO-2006 in Children Under 5 Years in Central Area of Peru. Universal Journal of Public Health. 2014;2(2): 73-81. |

| [23] | Lechtig A. Evaluación Externa del Programa Buen Inicio. USAID-AISA. Agencia Internacional de Seguridad Alimentaria. Lima. Perú. 2007. |

| [24] | Castro, J. Sistematización del Programa Corazón en Familia. Informe de sistematización. Visión Mundial Perú. Lima. Perú. 2007. |

| [25] | WVI Peru. Línea de Cierre del Programa Corazón en Familia. World Vision International - Perú. Lima, Perú. 2006. |

| [26] | Castro J, Chirinos D. Informe de Línea de Base del Proyecto Mejoramiento de la Seguridad Alimentaria Nutricional de Familias Campesinas de la Región Junín. CÁRITAS Huancayo. Perú. 2008. |

| [27] | Castro J, Chirinos D, Ríos E. Estudio Basal de la Seguridad Alimentaria Nutricional en el Distrito de Janjaillo-Jauja. Instituto de Seguridad Alimentaria Nutricional, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. Lima. Perú. 2009. |

| [28] | Beaton G, Kelly A, Kevany J, Martorell R, Mason J. Appropriate Uses of Anthropometric Indices in Children. - Nutrition Policy Discussion. Paper No.7, A report based on an ACC/SCN Workshop. Geneva. 1990. |

| [29] | INS. La medición de la talla y el peso. Guía para el personal de la salud del primer nivel de atención. Centro Nacional de Alimentación y Nutrición - Instituto Nacional de Salud/UNICEF. Lima. Perú. 2004. |

| [30] | Morris SS, Ruel MT, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG, de la Briere B, Hassan MN. Precision, accuracy, and reliability of hemoglobin assessment with use of capillary blood. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999; 69 (6):1243-8. |

| [31] | Neufeld L, Garcia-Guerra A, Sanchez-Francia D, Newton-Sanchez O, Ramirez-Villalobos MD, Rivera- Dommarco J. Hemoglobin measured by Hemocue and a reference method in venous and capillary blood: a validation study. Salud Publica Mex. 2002; 44(3):219-27. |

| [32] | Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 7th ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press. 1980. |

| [33] | ENDES. Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. INEI. Lima. Perú. 2012. |

| [34] | PRISMA. Proyecto Salud Integral. Asociación privada para el desarrollo agropecuario y el bienestar social. Informe final. Lima. Perú. 2010. |

| [35] | CARITAS-Loreto. Informe final del proyecto “Familias saludables en comunidades indígenas”. Lima. Perú. 2010. |

| [36] | CARITAS-Ancash. Informe final del Proyecto “Ally Micuy. Lima. Perú. 2010. |

| [37] | Gerald J, Friedman D. Reducción de la desnutrición crónica en el Perú: Propuesta para una Estrategia Nacional. School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. Lima. Perú. 2001. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML